The COVID-19 pandemic is making it even more clear how interconnected health is with other areas of life such as economic security, education, food security and housing stability. Investments in health care systems and public health infrastructure have been an important part of the pandemic response. But we are also seeing how non-health care sector supports like unemployment benefits, food assistance and direct payments to individuals are critical to adequately respond to this public health emergency. Researchers estimate that these social and economic factors, called social determinants of health, account for about 40 percent of the health outcomes we see. They often play a bigger role in the health of the population than direct health care services, or clinical care, which account for about 20 percent of health outcomes.[1]

Housing is one of the social determinants of health that requires increased attention, as most states issue stay at home orders as part of their response to COVID-19. Stable, quality housing gives people a place to safely practice social distancing, provides access to necessary utilities to wash their hands and for online school and work activities and offers protections from further financial instability. This report will discuss the relationship between health and housing in Georgia, including how Georgians are faring in terms of housing stability, affordability, quality and homelessness. The report will include some key recommendations for how state leaders can support housing to improve health outcomes during the immediate COVID-19 response, as well as ways to support housing for better health beyond the emergency period.

Health and Housing in Georgia

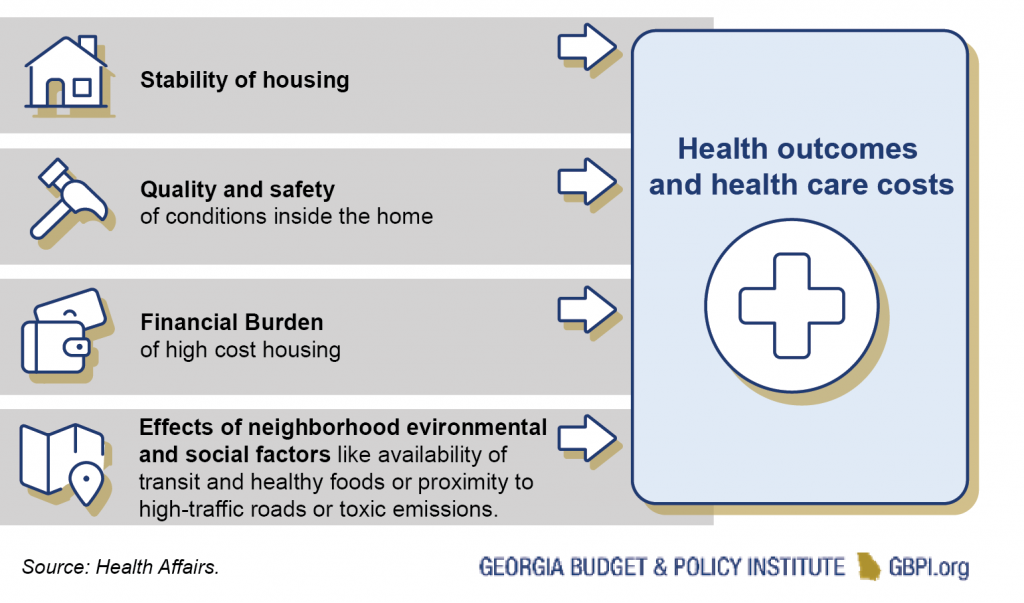

Housing influences health outcomes in a few different ways. A policy brief published in Health Affairs lays out four ways in which housing and health are connected, based on the large body of health and housing research.[2] The four pathways include the stability of housing, the quality and safety of conditions inside the home, the financial burden of high-cost housing and the effects of neighborhood environmental and social factors like availability of transit and healthy foods or proximity to high-traffic roads or toxic emissions.

Housing Stability and Health in Georgia

People who are in unstable housing situations (such as those who need to move multiple times in a year or have difficulty paying rent) or who are experiencing homelessness face poorer health outcomes than people with stable housing. For example, children who move three or more times a year are more likely to have chronic conditions and less likely to have consistent health insurance coverage. Providing stable housing to people facing housing instability helps improve their health and reduces costs to hospitals and state health programs like Medicaid. As many people face furloughs or layoffs due to COVID-19 and could be unable to make their rent or mortgage payments, support for stable housing is critical. Keeping people housed will also help promote the public health goal of slowing the spread of the virus by preventing people from moving constantly and reducing the number of people living outdoors or in crowded places where there is increased exposure to the virus.

People who are in unstable housing situations (such as those who need to move multiple times in a year or have difficulty paying rent) or who are experiencing homelessness face poorer health outcomes than people with stable housing. For example, children who move three or more times a year are more likely to have chronic conditions and less likely to have consistent health insurance coverage. Providing stable housing to people facing housing instability helps improve their health and reduces costs to hospitals and state health programs like Medicaid. As many people face furloughs or layoffs due to COVID-19 and could be unable to make their rent or mortgage payments, support for stable housing is critical. Keeping people housed will also help promote the public health goal of slowing the spread of the virus by preventing people from moving constantly and reducing the number of people living outdoors or in crowded places where there is increased exposure to the virus.

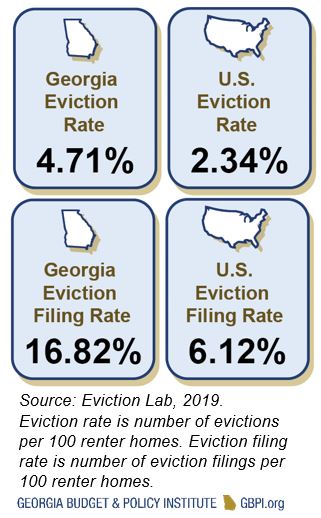

Due to housing instability, people facing eviction or foreclosure can experience negative health outcomes. The number of evictions and eviction filings per 100 renters in Georgia is more than two times higher than the national average. Seven of the 30 mid-size cities with the highest eviction rates are in Georgia—including Redan, Union City, East Point, Candler-McAfee, Warner Robins, Carrollton and Rome. Renters in Georgia face a higher cost burden than homeowners, leaving them more vulnerable to instability. In 2017, 46 percent of Georgia renters were cost-burdened because they spent more than 30 percent of their household income on rent. For Georgia homeowners, 20 percent were cost-burdened.[4] Although homeowners are less likely to be cost burdened than renters, there has been a recent increase in foreclosures. Foreclosures have declined nationally since the recession, but Georgia saw a 24 percent year-over-year increase in foreclosures in 2019.[5]

Due to housing instability, people facing eviction or foreclosure can experience negative health outcomes. The number of evictions and eviction filings per 100 renters in Georgia is more than two times higher than the national average. Seven of the 30 mid-size cities with the highest eviction rates are in Georgia—including Redan, Union City, East Point, Candler-McAfee, Warner Robins, Carrollton and Rome. Renters in Georgia face a higher cost burden than homeowners, leaving them more vulnerable to instability. In 2017, 46 percent of Georgia renters were cost-burdened because they spent more than 30 percent of their household income on rent. For Georgia homeowners, 20 percent were cost-burdened.[4] Although homeowners are less likely to be cost burdened than renters, there has been a recent increase in foreclosures. Foreclosures have declined nationally since the recession, but Georgia saw a 24 percent year-over-year increase in foreclosures in 2019.[5]

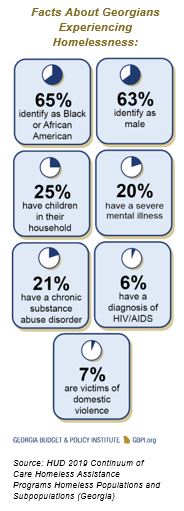

People experiencing homelessness often face additional risks from housing instability because of their demographics and increased exposure to others. The 2019 point-in-time homeless count survey found that at least 4,183 people in Georgia experienced homelessness.[6] The number of people counted as homeless during this biennial survey has steadily declined in Georgia since 2013, but there was a 13 percent increase from 2017 to 2019. Chronic homelessness is associated with higher rates of physical and mental illness as well as shorter life expectancy.[7] People experiencing homelessness are at higher risk during the COVID-19 pandemic because of limited ability to distance themselves; they are also older and in poorer health than the general population and have limited access to cleaning and hygiene facilities to do handwashing and adhere to other guidance.[8]

Housing Affordability and Health in Georgia

Housing affordability plays a big role in the housing stability and health pathway, but the stress of paying for costly housing and the lack of resources left for other needs after spending a high percentage of income on housing also affect health outcomes. A study of more than 16,000 adults with low incomes found that those who reported trouble paying rent, mortgage or utility bills in the past year were more likely to postpone needed medical care and medications and more likely to have limited or uncertain availability of food.[9] Children in low-income families receiving housing subsidies are more likely to have access to nutritious food and report good or excellent health compared to similar families who are not receiving housing assistance.[10]

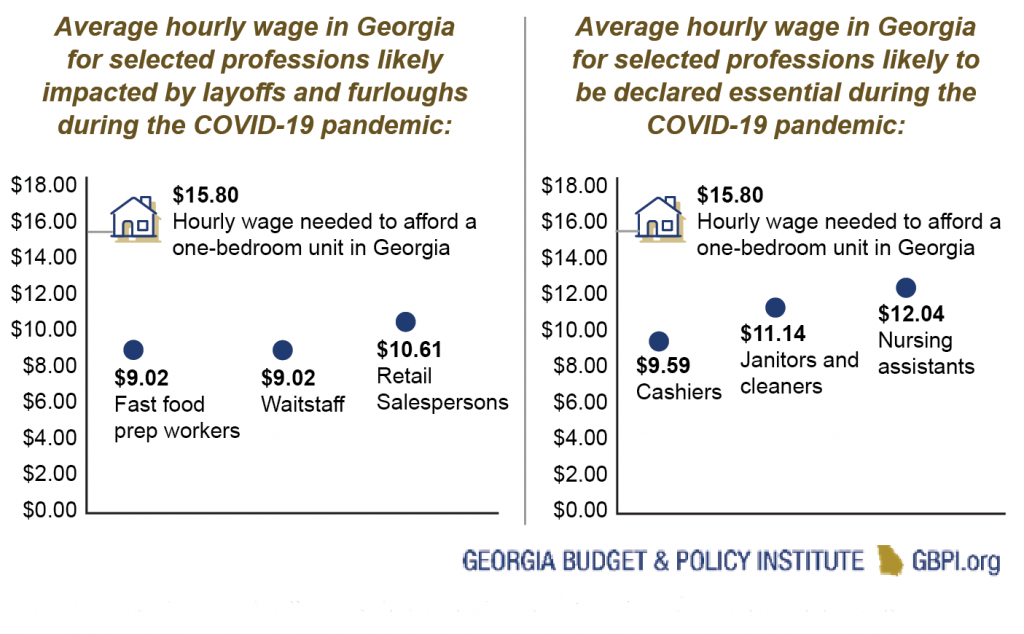

Many workers in the industries whose employment is most at risk due to the impacts of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic already did not earn enough to afford the average one bedroom in Georgia. They likely were already spending a higher percentage of their income on housing, limiting their savings and ability to pay for rent during this economic crisis when they may be losing income. Low-wage workers in frontline industries like grocery stores and health care may also face housing affordability challenges. These challenges can take a toll on mental health and can limit their ability to secure housing that allows them to prevent infecting other household members.

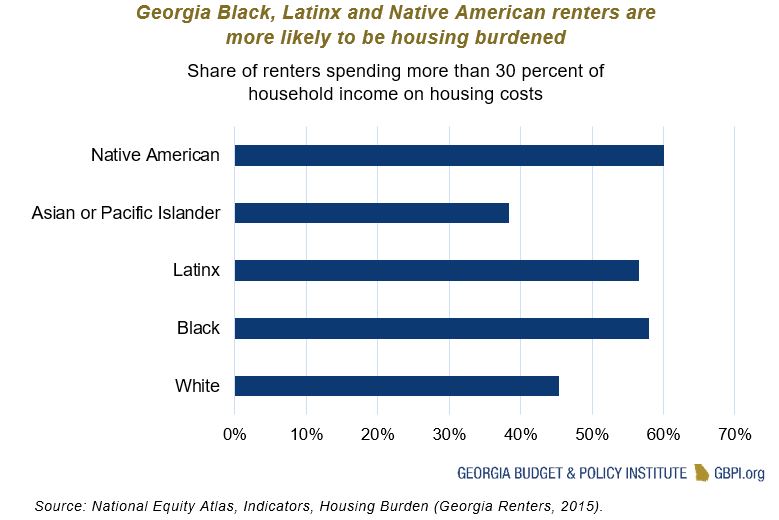

Black Georgians make up half of the deaths from COVID-19 but represent about 30 percent of the state’s population.[11] Black Georgians and other communities of color were some of the hardest hit by policies such as redlining practices that banned people of color from getting mortgages, as well as the housing crisis of the Great Recession. These communities are still recovering from the effects of housing discrimination and foreclosures on homeownership rates, home values and reduced opportunities to build wealth. A higher share of Georgia renters of color than whites are cost-burdened by housing, spending more than 30 percent of income on rent.[12]

Similar to difficulties affording rent or mortgage payments, struggling to afford utility bills can contribute to mental health disorders like anxiety and depression.[13] Having consistent access to utilities, including basic cooking appliances, safe drinking water, electricity and/or gas and internet access is important during the COVID-19 pandemic. While broadband internet has typically not been included as a utility that people need, the pandemic has made it clear how necessary internet access has become in our society, as children need computer and internet access to finish the school year and many people are working from home. Internet access also plays a critical role now to maintain social connections with friends and family, which also has proven health benefits.[14] About 8 percent of Georgia’s population lives in areas underserved by broadband, defined as a minimum speed of 25Mbps download and 3Mbps upload. Most of the counties with limited broadband access are rural counties in South Georgia.[15]

Housing Quality and Neighborhood Factors in Georgia

Housing affordability and stability are more commonly discussed when thinking about housing policy issues. In the last two years, Georgia Budget and Policy Institute staff members have traveled across the state to host listening sessions with local organization and community members, including in Rome, Albany, Savannah and metro Atlanta. Many people discussed challenges with affording housing, but we also heard Georgians discuss their challenges with obtaining good quality housing that did not have environmental health hazards or significant structural issues. Environmental factors inside the home and the neighborhood outside of the home have an effect on health. When children are exposed to poor housing conditions such as lead, substandard water quality, poor ventilation and pest infestation, they are more likely to have poor health outcomes.[16] Some chronic conditions like asthma can be aggravated by poor housing conditions. People with chronic conditions are more at risk of complications from contracting COVID-19. Residential crowding, another housing quality issue, is associated with illness and psychological distress, and it also has clear effects during this pandemic as social distancing is one of the most successful mitigation strategies.[17], [18]

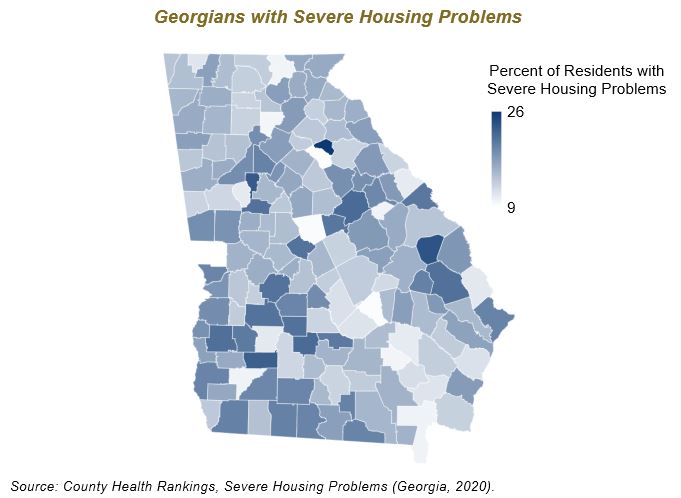

There are many different measures of housing quality. One survey looks at households that report at least 1 of 4 housing issues—overcrowding, high housing costs, a lack of kitchen facilities, or a lack of plumbing facilities—and consider these households to have “severe housing problems.” Many of the state’s counties with higher share of households experiencing severe housing problems are in Southwest Georgia where there are also higher rates of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Other measures of housing quality include access to safe drinking water. Georgia was ranked No. 5 of all states with the most offenses of the Safe Drinking Water Act in 2015.[19]

The safety and resource availability in the area surrounding the home also plays a role in health. Having access to safe spaces to exercise and to get healthy foods can facilitate better health outcomes, while neighborhood factors such as industrial operations, traffic emissions, blight and segregation can negatively affect health.[20] The state can promote better housing quality through investments in improving housing conditions and enacting regulations to ensure new and existing housing meet quality standards.

State Health and Housing Policy Recommendations For COVID-19 Response and Beyond

Although housing in the United States is largely run by the private sector, government has always contributed through financing housing costs and overseeing development. Many of the policy solutions to promote health and housing occur at the local level, with policies like zoning and local taxes and fees that can fund housing development, or at the federal level, with housing subsidies and federally backed mortgages. But state leaders can also play a role through changes to regulations and court processes, ensuring state preemption does not stifle local governments’ ability to create more affordable housing and establishing funds to provide emergency housing assistance and affordable housing development.

Health and Housing Recommendations for Immediate Response to COVID-19

1. Put a temporary ban on eviction, foreclosures and utility shutoffs during the COVID-19 emergency period.

Federal legislation put a temporary moratorium on eviction filings for 120 days, but it only covers about 28 percent of the nation’s rental units.[21] Georgia can implement a statewide moratorium on evictions and foreclosures to ensure housing stability during this emergency period. The state can also help families with recovering after the emergency period ends by extending moratoria for at least 30 or more days beyond the emergency declaration, depending on how soon people are able to return to work. Most utility companies in Georgia are suspending disconnection due to COVID-19, but some require families to prove hardship and some are suspending but not waiving late fees.[22] Statewide action to suspend utility shutoffs and directing utility companies to waive late fees will provide uniform action to protect families’ health.

2. Provide financial assistance to help people pay their rent, mortgage or utility bills or to catch up on missed payments after any rent or mortgage moratoria expire.

While the moratoria proposed above are key to ensuring housing stability during the crisis, families will still have to make the payments after temporary bans end. They may not return to work right away or they may not earn enough to catch up on past payments while keeping current on upcoming bills. Financial assistance for these families will help protect housing stability and reduce the harmful health effects that come with the inability to pay for basic needs. The federal government has made efforts to increase financial assistance to families through a direct stimulus payment and increases to unemployment benefits, but continued support is needed as the economy continues to struggle. Some states are also providing financial assistance through their housing trust funds, including Florida, where local governments have the option to use these funds for emergency rent, mortgage and utility payments during the COVID-19 pandemic.[23]

3. Coordinate a collaborative emergency housing response to support people with immediate housing needs such as people leaving jails, prisons or detention centers, domestic violence and sexual assault survivors and people experiencing homelessness.

Groups with immediate housing needs would benefit from state efforts to coordinate the work of federal and local government agencies and nonprofit service providers to secure and fund emergency housing. The state has taken positive steps by creating the Committee for the Homeless and Displaced as one of the Governor Kemp’s four Coronavirus Task Force Committees. One of their recommendations is for the state to establish a coordination center led by the Department of Community Affairs to facilitate multi-agency efforts focused on people who are homeless and displaced.[24] The Governor also has emergency powers, which are currently set to expire on June 12, that can allow him to provide emergency housing during the emergency period and should consider ways to use this power to meet urgent housing needs.

Organizations who work with and advocate for people who are homeless, survivors of domestic violence and people involved in the criminal justice system have put forward recommendations the state can consider to meet the needs of populations with urgent housing needs. The National Health Care for the Homeless Council recommends immediate actions to identify appropriate isolation and quarantine facilities, ensure homeless service providers have personal protective equipment and provide health care support through Medicaid expansion and allowing for 90-day supplies of medications.[25]

The National Network to End Domestic Violence is advocating for increased federal support for transitional housing and improving access to cash assistance through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).[26] At the state level, Georgia can also leverage TANF by deploying the $67 million in unobligated reserve money to provide up to four months of short-term assistance to families with children.[27]

People who are incarcerated in jails, prisons and detention centers are at a higher risk of exposure to the virus, and some jails are releasing people to reduce the spread. When people are released due to COVID-19 concerns or other reasons, they need assistance to ensure they are stably housed and not putting themselves or others at risk of exposure during the pandemic. Georgia can help connect the formerly incarcerated with housing and ensure they are not reincarcerated because of supervision violations like unpaid fees or failure to maintain steady employment during this public health and economic crisis.[28] Stable housing and preventing reincarceration helps reduce the spread of COVID-19 both outside and inside prison.

Health and Housing Recommendations to Implement Throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond

4. Ensure state legislation does not preempt local government from pursuing affordable housing and work support policies.

Preemption is “the use of state law to nullify a municipal ordinance or authority.”[29] Georgia has laws allowing the state to preempt local policies such as those related to minimum wage, paid leave, ride sharing and rent control.[30] Increasing minimum wage or access to paid leave can help families who do not earn enough to afford the average rental unit and prevent them from losing their income due to caregiving and other responsibilities. Research on minimum wage and the effects on health show that increases in minimum wage decrease smoking and increase birthweights of babies born in families with low-wage workers.[31] And research on paid family leave and health find that children see immediate and long-term health benefits if their parent received paid family leave, including a reduction in infant hospitalizations and reduction in rates of overweight among elementary school-age children.[32] Georgia lawmakers should work in partnership with local governments to ensure preemption laws do not prevent the development of affordable housing or financial support for working families.

5. Expand the scope of Georgia’s state housing trust fund and increase investment in the fund.

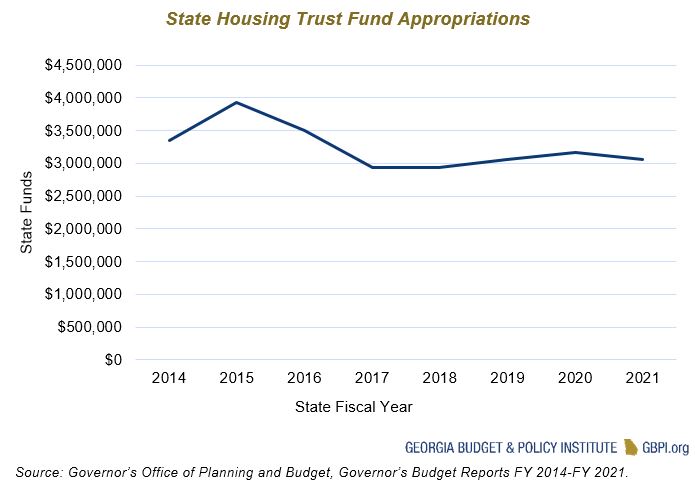

Georgia currently has a state-funded housing trust fund for the homeless, and this fund was created in 1988. The funds are used to support non-profit organizations who provide services to people experiencing homelessness. The state funds are matched with federal funding. Every $1 of state money put into the fund pulls down $8 in federal funding.[33] Georgia uses general funds for the housing trust fund, and the funding level has mostly been flat in the past several years.

Georgia can look at different revenue sources to increase the amount of funding available. Some states use dedicated revenue sources such as document recording fees and real estate transfer taxes to fund their housing trust funds.[34] The state can also pursue legislation to encourage cities and counties to establish their own local housing trust funds. Fourteen states passed legislation encouraging or enabling local jurisdictions to dedicate public funds to affordable housing.[35] Georgia’s housing trust focuses on supporting non-profit homeless service providers, but housing trust funds can also be used to leverage public/private funding sources to build affordable housing. For example in Michigan, every $1 of their housing trust fund leveraged $11 of public and private sources, generating thousands of jobs and millions of dollars in state and local taxes.[36] Georgia leaders should consider ways to expand the scope of what the existing trust fund can cover or start a separate state housing trust fund focused on improving housing affordability—which will have positive health benefits.

6. Enact regulations and pursue funding to ensure more people live in good quality housing and have access to needed utilities.

There are many policy options Georgia can pursue to better protect renters from housing instability and/or poor housing quality and to ensure tenant due process. The Georgia Healthy Housing Coalition of health and housing advocacy organizations has a number of relevant recommendations for state lawmakers such as establishing a statutory warranty of habitability, extending the number of days before filing eviction notices and protecting tenants from retaliatory eviction for filing complaints about unhealthy housing conditions (the retaliatory eviction ban passed in the legislature in 2019).[37] A statutory warranty of habitability is a promise a landlord makes to keep a property safe and livable, and conditions a tenant’s obligation to pay rent on the landlord’s keeping that promise.[38] The state should also consider providing a tenant with greater time in which to pay back rent, as Georgia law currently permits a landlord to immediately terminate a lease for nonpayment of rent.[39] Lastly, the state can support tenants in better understanding their rights if their housing stability is at risk. The state should explore innovative ways to connect renters and homeowners with legal resources in the event they face eviction or foreclosure and require landlords to provide clear explanations of lease language, with translation into a tenant’s native language.

In addition to legislation, state and local governments can pursue federal funding opportunities to weatherize homes and address structural issues. Improving housing quality is not only important to ensure safe housing conditions during COVID-19, but also because we are currently in an emergency period for storm damage and could move into other disaster periods such as hurricanes. Furthermore, collecting more information about housing quality issues in the state will help to better target resources. The state can build on efforts like the Department of Public Health’s tracking of lead exposure in homes and consider tracking and responding to other home hazards that can contribute to poor health. Lastly, the state should continue to expand broadband internet access, which is now a necessity for many adults to work and to support children’s educational development.

7. Enhance health care sector spending on housing supports and encourage providers to take the housing first approach for patients facing housing insecurity

Supportive housing is a successful model that combines stable, affordable housing and intensive case management and support services for people at risk of homelessness and who have physical or mental health needs. The state has made major investments in supportive housing through the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities since 2011 and the state should maintain and enhance funding for supportive housing units to meet demand. Medicaid can also support innovative health and housing models; it already covers some services provided in supportive housing settings such as mental health and substance abuse treatment. But it could also be used to cover more of these services through Medicaid expansion to cover adults with low incomes, and federal 1115 waivers can be used to allow Medicaid to pay for certain housing supports like help finding housing, tenant rights education and home safety modifications.[40]

Housing First is another successful approach that prioritizes providing permanent housing to people experiencing homelessness as a platform for helping them meet their other needs—instead of requiring them to address certain challenges before getting housed. The state behavioral health agency recently launched a pilot program to implement the housing first model and provide housing support to 180 people with severe and persistent mental illness. As the state continues its work to provide supported housing under a Department of Justice legal settlement, expanding use of evidence-based approaches like Housing First can reach target populations.[41] Health care providers such as Good Samaritan Health Center and Mercy Care—two federally-qualified health centers—are also taking the housing first approach with their patients through integrated partnerships and co-locating affordable housing with health services. The Medicaid program and the care management organizations can encourage more efforts to integrate health and housing by using delivery system reform options to facilitate partnerships across sectors.[42]

Endnotes

[1] County Health Rankings. (2020). Measures & data sources | County health rankings model. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/measures-data-sources/county-health-rankings-model

[2] Taylor, L. (2018). Housing and health: An Overview of the literature. Health Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20180313.396577

[3] The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Housing instability | Healthy people 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/housing-instability

[4] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. (2019). The state of the nation’s housing 2019. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/state-nations-housing-2019

[5] ATTOM Data Solutions. (2020, January 15). U.S. foreclosure activity drops to 15-year low In 2019. https://www.attomdata.com/news/market-trends/foreclosures/attom-data-solutions-2019-year-end-u-s-foreclosure-market-report/

[6] Georgia Department of Community Affairs (2019). Georgia balance of state continuum of care point in time homeless count: 2019 report. https://www.dca.ga.gov/sites/default/files/coc_report_2019_-_print_file_4.pdf

[7] National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2019). Homelessness & Health: What’s the Connection? https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/homelessness-and-health.pdf

[8] National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2020). COVID-19 & the HCH community: Needed policy responses for a high-risk group. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Issue-brief-COVID-19-HCH-Community.pdf

[9] Kushel, M. B., Gupta, R., Gee, L., & Haas, J. S. (2006). Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x

[10] Maqbool, N., Viveiros, J., & Ault, M. (2015). The impacts of affordable housing on health: A research summary. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339366232_The_Impacts_of_Affordable_Housing_on_Health_A_Research_Summary

[11] Georgia Department of Public Health. (2020). COVID-19 status report. https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-daily-status-report

[12] PolicyLink/PERE, National Equity Atlas. (2020). National Equity Atlas. https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Housing_burden/By_race%7Eethnicity%3A49756/Georgia/false/Year%28s%29%3A2015/Tenure%3ARenters

[13] Hernández, D. (2016). Understanding ‘energy insecurity’ and why it matters to health. Social Science & Medicine, 167, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.029

[14] Holt-Lunstad, J., Robles, T. F., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000103

[15] Georgia Department of Community Affairs’ Georgia Broadband Deployment Initiative. (2020). Phase 1 unserved Georgia by county. https://broadband.georgia.gov/maps/unserved-georgia-county

[16] Braveman, P., Dekker, M., Egerter, S., Sadegh-Nobari , T., & Pollack, C. (2011). Housing and health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/05/housing-and-health.html

[17] Solari, C. D., & Mare, R. D. (2012). Housing crowding effects on children’s wellbeing. Social Science Research, 41(2), 464–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.09.012

[18] Koo, J. R., Cook, A. R., Park, M., Sun, Y., Sun, H., Lim, J. T., Dickens, B. L. (2020). Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore: A modelling study. The Lancet: Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30162-6

[19] Fedinick, K., Wu, M., Panditharatne, M., & Olson, E. (2017). Threats on tap: Widespread violations highlight need for investment in water infrastructure and protections. Natural Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/resources/threats-tap-widespread-violations-water-infrastructure

[20] Richey, K. (2019). Why Place Matters: Data on health, housing and equity. Oklahoma Policy Institute. https://okpolicy.org/why-place-matters-data-on-health-housing-and-equity/

[21] Harker, L. (2020). Support healthy communities in Georgia with a temporary eviction ban. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2020/support-healthy-communities-in-georgia-with-a-temporary-eviction-ban/

[22] Georgia Emergency Management and Homeland Security and Georgia Public Service Commission. (2020, May 5). Georgia’s service postponements. https://psc.ga.gov/

[23] Florida Housing Coalition (2020). COVID-19 SHIP frequently asked questions. https://www.flhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19-SHIP-FAQ-on-April-29.pdf

[24] Committee for the Homeless and Displaced. Final recommendations. March 24, 2020. Georgia Municipal Association. https://www.gacities.com/GeorgiaCitiesSite/media/PDF/COVID-19/Committee-for-the-Homeless-and-Displaced_Final-Recommendations.pdf

[25] National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2020). COVID-19 & the HCH community: Needed policy responses for a high-risk group. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Issue-brief-COVID-19-HCH-Community.pdf

[26] March 19, 2020 Sign-On Letter led by the National Network to End Domestic Violence and the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence. https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track/?pageNum=6&uri=urn%3Aaaid%3Ascds%3AUS%3A48b630a5-1dc5-45fb-8bd2-38488e9aefa6

[27] Camardelle, A. (2020). TANF funding and COVID-19: A critical opportunity. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2020/tanf-funding-and-covid-19/

[28] Pham, D., & Bird, K. (2020). COVID-19 response must include youth and adults impacted by the criminal justice system. Center for Law and Social Policy, Inc. https://www.clasp.org/blog/covid-19-response-must-include-youth-and-adults-impacted-criminal-justice-system

[29] DuPuis, N., Langan, T., McFarland , C., Panettieri, A., & Rainwater, B. (2018). City rights in an era of preemption: A state-by-state analysis 2018 update. National League of Cities. https://www.nlc.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Restoring-City-Rights-in-an-Era-of-PreemptionWeb.pdf

[30] Schragger, R. (2017). State preemption of local laws: Preliminary review of substantive areas. Legal Effort to Address Preemption (LEAP) Project. https://www.abetterbalance.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/State-Preemption-of-Local-Laws.pdf

[31] Leigh, J. P., & Du, J. (2018). Effects Of Minimum Wages On Population Health. Health Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20180622.107025

[32] Rossin-Slater, M., & Uniat, L. (2019). Paid Family Leave Policies And Population Health. Health Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20190301.484936

[33] Georgia Department of Community Affairs. State Housing Trust Fund for the Homeless Commission, Annual report: 2018. https://issuu.com/ga_dca/docs/state_htf_annual_report

[34] Housing Trust Fund Project. (2020). State housing trust fund revenues 2020. https://housingtrustfundproject.org

[35] Housing Trust Fund Project. (2020). State enabling legislation. https://housingtrustfundproject.org

[36] AcMoody, J. (2018). Fund the fund: Why Michigan’s Housing and Community Development Fund needs support. Community Economic Development Association of Michigan (CEDAM). http://cedamichigan.org/2018/06/michigans-community-development-fund/

[37] Georgia Appleseed Center for Law & Justice. (2020). Georgia Healthy Housing Project: Advocating for safe, healthy, and stable Housing. https://gaappleseed.org/initiatives/healthy-housing

[38] Miller, A. (2019, March 5). Ga. Bill would protect tenants facing unhealthy living conditions. WABE Atlanta. https://www.wabe.org/ga-bill-would-protect-tenants-facing-unhealthy-living-conditions/

[39] GA. CODE ANN. § 44-7-50(a).

[40] Harker, L. (2019). Opportunities for Georgia to best leverage Medicaid waivers. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2019/opportunities-for-georgia-to-best-leverage-medicaid-waivers/

[41] Report of the Independent Reviewer in the Matter of United States v. The State of Georgia Civil Action No. 1:10-CV-249-CAP. (2020, January 31). Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. https://dbhdd.georgia.gov/organization/be-informed/reports-performance/ada-settlement-agreement

[42] Katch, H. (2020). Medicaid can partner with housing providers and others to address enrollees’ social needs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-can-partner-with-housing-providers-and-others-to-address-enrollees-social

1 thought on “Georgia’s COVID-19 Public Health Response Must Include Support for Stable, Quality Housing”

my name is patricia smith. i am the mother of two grown children and the grandmother of eight grand-children. i see the hardship my daughter is going through under this heavy burden americans a suffering under covid-19. my daughter was married but is now going through a painful seperation due to personal problems in their relationship. she is the sole provider for her eight children. she is trying to hold a job that pays her barely 150 a week due to covid and 194.00 monthly in food stamps. she pays 1500. in rent and has overages in water and light. the battering has been relentless. she is not eating and sleeping due to these overwhelming pressure to provide for her family. she receives no child support. due to the unavailability of certain legal services because of covid. she feels its within a matter of time when she know longer can provide for her family. she is slipping through the cracks. who helps her and those like her? we have tried to reach out to various organizations only to be put on hold, due to high demand, and to get answers. yet in return all we gotten are only more questions than answers. we are not looking for hand out but help and guidance, to sift through the various tricksters that have come out of the woodwork to profit off of others misery.