Introduction

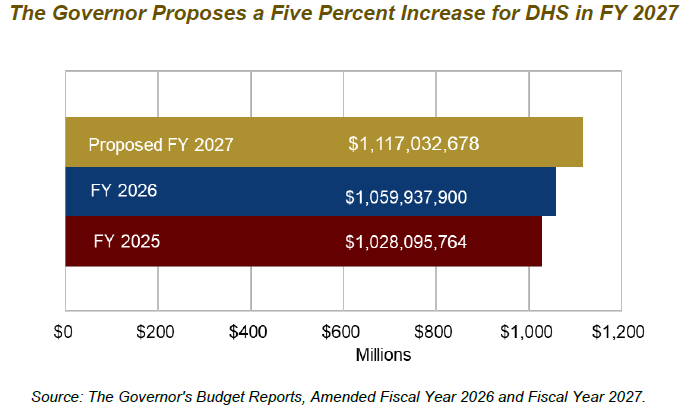

The Department of Human Services (DHS) oversees various services including foster care, child welfare, support for low-income individuals, aging services and child support.[1] Governor Kemp proposed allocating $1.13 billion to DHS in the Amended Fiscal Year (AFY) 2026 budget and $1.12 billion to the department in Fiscal Year (FY) 2027. The governor’s proposed FY 2027 budget DHS budget is 5.4% greater than the FY 2026 budget.[2]

Governor Kemp’s budget includes resources to help the agency navigate different fiscal shortfalls projected for AFY 2026 and FY 2027. In the fall of 2025, DHS’ Division of Family and Children Services announced that the foster care system had a projected $80 million shortfall due to the rising costs of caring for children in the foster care system.[3] Additionally, H.R. 1, federal tax and spending legislation that passed in July 2025, requires states to take up a greater share of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) administration costs starting in October of 2026. As appropriators consider spending plans for DHS, they should think strategically about funding investments that promote family stability, prevent family separation and reduce long-term costs.

Budget Highlights for DHS

Amended FY 2026 Proposed Changes

The governor’s proposed budget would add about $72.6 million to the DHS budget for the remainder of the 2026 fiscal year. Most of the proposed AFY 2026 budget would be for a one-time salary increase and funding for foster care.

- $41.5 million increase to the foster care program for increased utilization and the increased costs of care

- $22.4 million increase to provide one-time $2,000 salary increases for all full-time DHS staff

- $6.2 million in one-time funds to modify the Gateway eligibility system to address SNAP payment error rates

FY 2027 Proposed Changes

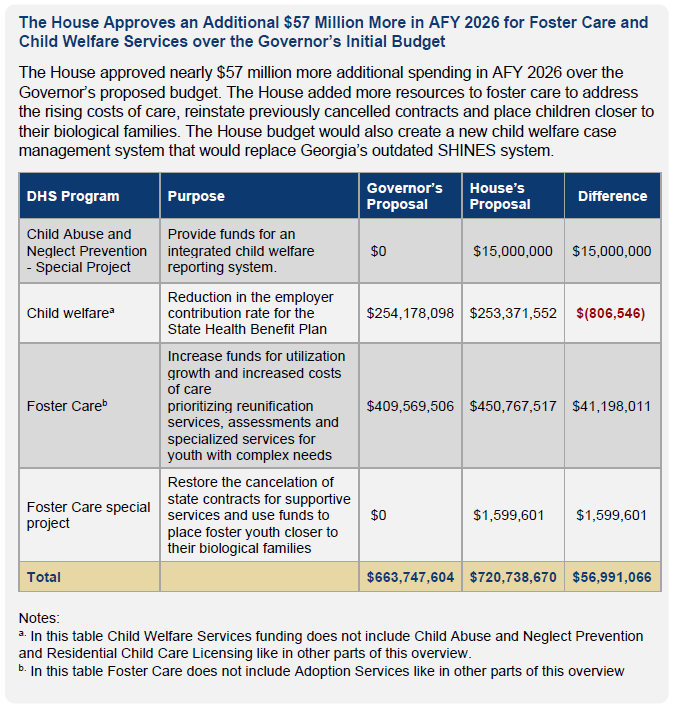

The proposed changes in the Governor’s FY 2027 budget increase DHS funding by $57 million. It includes:

- Increased funding for foster care:

- A $21.3 million increase for foster care for increased utilization and the increased cost of care

- A $6.2 million transfer from the Exploited Children Fund Commission to foster care intended to support agency efforts to address child trafficking

- Increased funding for SNAP administration to address the federal cost shift caused by H.R.1:

- $40.4 million increase to the Division of Family and Children Services for SNAP administration (determining and processing SNAP benefits)

- $12 million increase for an initiative to improve SNAP benefit accuracy and reduce the payment error rate

- $5.9 million increase to DHS agency administration to cover the loss of federal funds due to the cost shift

Service Reductions and Proposed State Funding Should Close Most of the Foster Care Shortfall for AFY 26; It’s Unclear if the Changes Will Prevent a Future Shortfall for FY 27

The Governor’s AFY 2026 budget provides $41.5 million for foster care to address the projected program deficit of $85.7 million. The fiscal concerns of the agency first came to light during the 2025 legislative session when DHS Commissioner Broce requested $44 million for AFY 25 and FY 2026.[4] The legislature approved $38.5 million for AFY 2025 but only approved $19.3 million for FY 2026. DHS started FY 2026 with resources below their projected shortfall. However, that shortfall expanded beyond initial projections.

In November 2025, four months into the fiscal year, the DHS Commissioner announced a projected shortfall of more than $80 million and cancelled many contracts and established a new process for authorizing services.[5] In a December hearing, multiple providers described how these seemingly abrupt changes left a significant number of children without essential services and care and prevented birth parents from seeing their children.[6]

This year, the Commissioner has testified that most of the deficit for AFY 2026 should be covered through the governor’s proposed budget increase for foster care and a 25% reduction in costs. If necessary, the agency will also use more unobligated TANF reserve funds where applicable. However, the Commissioner has noted that TANF funds can only be used in limited circumstances for foster care.[7]

For FY 2027, the governor proposed adding $21.3 million for foster care from the original FY 2026 budget, while the agency continues to implement a 25% reduction costs. However, it is not clear that the agency is fully engaging in strategies that would control costs in the near or long term by preventing children from entering the system at all. Without such strategies, the agency may yet again have another shortfall.

Governor’s Budget Proposes State Resources to Address the Forthcoming Loss of Federal SNAP Administration Funding

H.R. 1 initiated the deepest spending cuts to SNAP and Medicaid in history to pay for tax cuts for the wealthy. Under the legislation, the state’s share of SNAP administrative costs will increase from 50% to 75% in federal fiscal year 2027. In subsequent years, the state will have to cover a share of SNAP benefits triggered by high SNAP payment error rates, which are mistakes by state caseworkers, or clients that result in over- or underpayments. Without legislative action to maintain administrative funding, the state will struggle to make enhancements that would reduce its high error rate and bring down future costs, which could range from $162 million to $487 million annually.

The Governor proposes $46.3 million in FY 26 (in DHS and DFCS administrative services) to keep funding for SNAP administrative costs level. The Governor’s budgets go even further to provide resources for DFCS to implement new strategies to address the error rates. In the proposed AFY 2026 budget, there is $6.2 million to update the Gateway system for SNAP error rate improvements and in proposed FY 2027 budget, $12 million for new strategies to identify and correct problems before they become payment errors. These proactive funding proposals could be an important component to lowering SNAP costs long-term.

Growing Evidence Suggests that Upstream Investments in Economic Security Programs Reduce Child Welfare Involvement and Costs

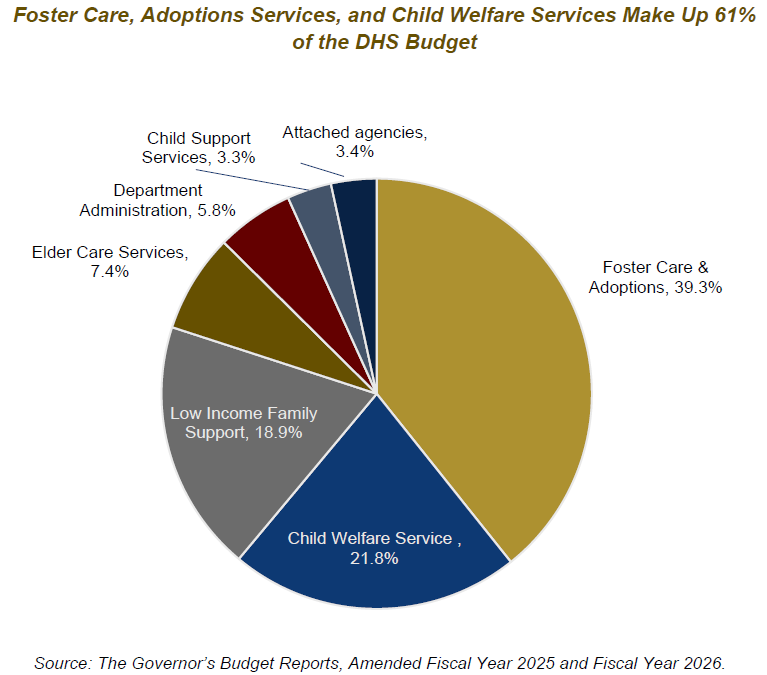

Georgia spends more than 60% of its DHS budget on child welfare, foster care and adoption services, while it spends only about 19% on Low Income Family Support programs, which include the administration of programs like cash and nutrition assistance that keep families financially stable.[8] However, the state may be able to reduce what it spends on foster care placements if it more fully adopted a prevention-minded approach. The Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 is structured so that states’ child welfare and foster care systems focus on evidence-based, family-stabilizing strategies that reduce separations and the reliance on congregate homes. Additionally, the state should also prioritize economic support programs as growing evidence points to their ability to reduce child welfare interactions.[9],[10]

This session, state leaders should consider this prevention strategy as they build on the Governor’s budget and deliberate on legislation. Lawmakers should:

-

Ask DHS what it needs to accelerate and/or expand Georgia’s Family’s First plan and invest in the strategy.[11]

For example, two home visiting models, Healthy Families America (HFA) and Parents as Teachers (PAT), are central components to Georgia’s plan. Home visiting is a family-centered approach where a health or family wellbeing professional provides in-home support to families with low income or who are at-risk of poor health outcomes. Many home visiting programs, like HFA and PAT, are evidence-based and have demonstrated positive outcomes like improved parent-child relationship and family economic stability.[12] Increased state investment can jump start and advance the DHS’ home visiting programs. Then the agency could draw down more federal resources. Furthermore, DHS could work with the Department of Public Health, which operates a separate home visiting program, and local governments to ensure there is at least one home visiting program in every county. -

Modernize the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) programs so that it can provide financial support to more families.

Currently, TANF funds are primarily used to fund government operations in child welfare, foster care and other programs instead of supporting core TANF activities of basic assistance, work supports and child care for families in poverty. TANF currently reaches about 3,500 families in Georgia.[13] The monthly TANF benefit level is $280 for a family of three and hasn’t changed since 1996. TANF is a foster care prevention program because most of the children receiving TANF benefits live with a relative. It is therefore critical to modernize the program and increase benefits and update eligibility levels to prevent deeper levels of poverty and to support families keeping children safe.

Endnotes

[1] There are four agencies that are attached to the DHS budget for administrative reasons: the Council on Aging, Georgia Vocational Rehabilitation Agency, Family Connect and the Safe Harbor for Sexually Exploited Children Fund Commission.

[2] Office of Planning and Budget. (2026, January). The Governor’s Budget Report, AFY 2026 and FY 2027, Governor Brian P. Kemp; House Bill 973, as passed by the House.

[3] Anderson, J. (2025, November 21). Financial trouble in Georgia’s child welfare agency results in mounting service cuts. The Imprint. https://imprintnews.org/top-stories/financial-trouble-in-georgias-child-welfare-agency-results-in-mounting-service-cuts/268878.

[4] Finch Floyd, I. (2025, February 12). Overview: 2026 fiscal year budget for the Georgia department of human services. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/overview-2026-fiscal-year-budget-for-the-georgia-department-of-human-services/?_gl=1*lvp33a*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTMzMDA0NDMxNy4xNzY5NTYxNjEz*_ga_ZWZC5HZ1YJ*czE3Njk1NjE2MTIkbzEkZzEkdDE3Njk1NjE3MTYkajM0JGwwJGgw.

[5] Anderson, J. (2025, November 21). Financial trouble in Georgia’s child welfare agency results in mounting service cuts. The Imprint. https://imprintnews.org/top-stories/financial-trouble-in-georgias-child-welfare-agency-results-in-mounting-service-cuts/268878.

[6] Appropriations Human Resources and Judiciary Juvenile Hearing. (2025, December 18). See foster care providers’ testimony from 3 hours 26 minutes to 6 hours 15 minutes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8Zeg7nCpSE&t=1293s.

[7] Georgia House Appropriations, Human Resources Subcommittee. (2026, January 23). See DHS Commissioner testimony from 51 minutes to 2 hours 17 minutes. https://vimeo.com/showcase/8988922?video=1152581091.

[8] In this analysis, “child welfare services” is inclusive of the budget lines for child welfare services, child abuse and neglect prevention, and residential child care licensing. Low-income support is inclusive of budget lines for support for needy families-basic assistance, support for needy families – work assistance, refugee assistance, federal eligibility benefit services, energy assistance, community services and out-of-school care.

[9] Puls, H. T., Hall, M., Anderst, J. D., Gurley, T., Perrin, J., & Chung, P. J. (2021). State spending on public benefit programs and child maltreatment. Pediatrics, 148(5), e2021050685. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-050685.

Tucker, L.P, Pergamit, M. and Bayer, M. (2023, October 31). How much does supportive housing save child welfare systems? Urban Institute. Washington, DC. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/How%20Much%20Does%20Supportive%20Housing%20Save%20Child%20Welfare%20Systems.pdf.

[10] Ginther, D.K., and Johnson-Motoyama, M. (2022, December). Associations between state TANF policies, child protective services involvement, and foster care placement. Health Affairs, 41(12), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00743.

Klevens, J., Barnett, SB., Florence, C., Moore, D. (2015, February). Exploring policies for the reduction of child physical abuse and neglect. Child abuse & neglect, 40, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.013.

Cai J. Y. (2022). Economic instability and child maltreatment risk: Evidence from state administrative data. Child abuse & neglect, 130(Pt 4), 105213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105213.

[11] Georgia Department of Human Services, Division of Family and Children Services. (2022). The family first prevention services act in Georgia: Blueprint for change. https://dfcs.georgia.gov/document/document/blueprint-family-first-one-sheet-may-2022/download.

[12] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. (2026). Home visiting evidence of effectiveness: Model search. https://homvee.acf.gov/models?field_miechv_eligible=1&meets-hhs=1&page=1.

[13] Georgia Department of Human Services, Division of Family and Children Services. (2024). Office of family independence data. https://dhs.georgia.gov/division-family-children-services-office-family-independence.