Georgia parents work hard every day to put food on the table and provide a brighter future for their children. Yet more than one in three of the state’s working families with children are likely to find themselves struggling to make ends meet due to low income.[1]

Nearly 392,000 working families with children are considered low-income in Georgia. These families are more likely to be forced into an interaction with the child welfare system, cope with unstable housing arrangements and suffer other hardships than families that earn more money. For nearly half of Georgia’s low-income working families, limited education keeps parents stuck in low-wage jobs.

A career pathways program is a proven way to help parents with low incomes secure college credentials and boost family incomes.[2] Students in Arkansas’ program completed higher education academic certificates and degrees at twice the rate of students enrolled in the same period who did not participate. Recent results from Arkansas also indicate that every dollar invested in career pathways produced about $1.79 in added taxes on earnings and reduced state spending.

Georgia can follow Arkansas’ lead and launch career pathways by dedicating about 9 percent of the state’s annual allocation from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families grant. This investment can help low-income Georgia parents secure in-demand college credentials, increase their incomes and lay the foundation for a brighter future for their children.

Too Many Parents Struggle with Jobs that Pay Too Little

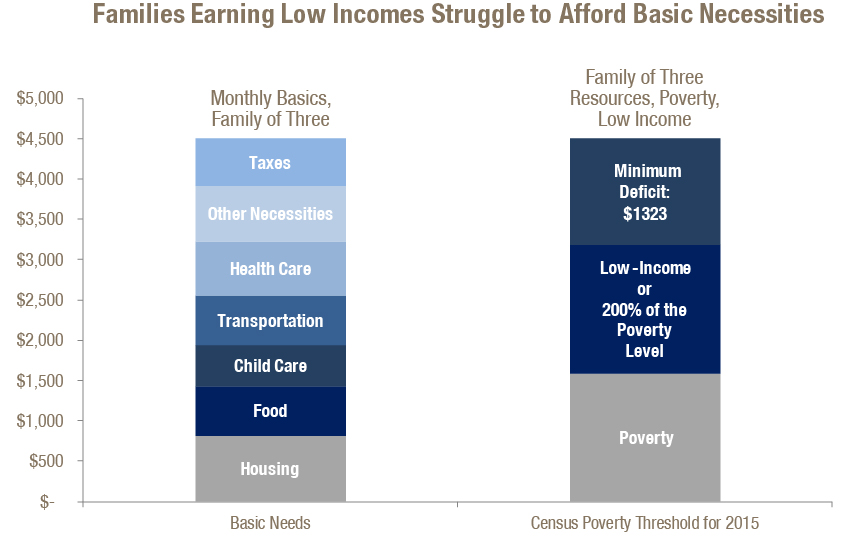

More than one in three of Georgia’s working families with children earn a low income. A low-income family of three earns less than $3,180 per month, or $1,323 less than what it takes to meet their basic needs in Gainesville, Ga. Parents who earn low incomes struggle to afford and sustain basic necessities for children, including adequate housing, food and clothing.

Low-paying jobs are driving this trend. Nearly 75 percent of Georgia’s low-income families include workers.[3] Eight of Georgia’s ten largest occupations are low-wage jobs. These occupations pay workers too little to support a family of three.

Too Many Jobs Pay Too Little to Support an Averaged-sized Family

Top Occupations in Georgia Ranked by Workers Employed

| Occupational Title | Employment | Median Annual Wage | As Share of Poverty Threshold | As Share of Basic Needs* | Education Required |

| Retail Salespersons | 141,860 | $24,880 | 130% | 45% | HS Diploma |

| Laborers and Freight, Stock, and Material Movers, Hand | 117,740 | $27,030 | 142% | 49% | HS Diploma |

| Combined Food Preparation and Serving Workers, Including Fast Food | 112,540 | $18,460 | 97% | 33% | Less than HS Diploma |

| Cashiers | 110,850 | $19,650 | 103% | 35% | HS Diploma |

| Customer Service Representatives | 103,170 | $34,300 | 180% | 62% | HS Diploma |

| General and Operations Managers | 90,520 | $114,070 | 598% | 205% | Bachelor’s Degree |

| Office Clerks, General | 83,920 | $28,820 | 151% | 52% | HS Diploma |

| Waiters and Waitresses | 79,130 | $19,200 | 101% | 34% | HS Diploma |

| Registered Nurses | 73,330 | $64,750 | 339% | 116% | Associate’s Degree |

| Secretaries and Administrative Assistants, Except Legal, Medical, and Executive | 60,320 | $35,060 | 184% | 63% | Associate’s Degree |

Sources: * “Basic Needs” represents the monthly costs for a family of two parents and one child in metro Atlanta. “Family Budget Calculator,” Economic Policy Institute, http://www.epi.org/resources/budget/. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupation and Employment Statistics, May 2016; U.S. Department of Labor “O*Net online http://www.onetonline.org/. “Education required” reflects the minimum education level reported by most respondents; Author’s calculation for “as share of poverty threshold.” Census poverty threshold used is for a family of three with one child.

Low Incomes Increase Chances of Child Welfare Interaction and Other Bad Outcomes

A family’s low income can lead them to interact with the child welfare system. Conditions associated with poverty, including inadequate food, shelter and clothing, are also associated with child neglect, which is the most common form of child maltreatment. A strong association exists between poverty and interaction with child welfare services in urban areas, according to a 2007 national study.[4] And children in low-income families experienced maltreatment at about five times the rate of other children, according to a 2010 national study.[5]

Inadequate housing is also a major factor in child neglect. Child welfare workers must often consider removing children from unsafe settings, even if they believe the parents are loving caretakers.[6] Children in low-income households are more likely to experience housing instability, overcrowding and unhealthy living conditions.[7]

Children who grow up with parents who earn low incomes are also at higher risk for academic underachievement, poorer health and behavior problems. Infants from low-income families score lower on cognitive assessments, are less likely to receive positive behavior ratings and are less likely to be in good health, according to an analysis of national data.[8] Fewer than half of poor children are school-ready by age five compared to three-fourths of middle- and high-income children. The study used a composite measure that weighed reading and math skills, learning-related and problem behaviors and overall physical heath.

Many factors link poverty and bad outcomes. Parents earning low wages can lack time and money to support their children’s learning in the way they prefer. Parents earning low incomes report they cannot spend as much time as they want reading to their children or helping with homework. Income insufficient to meet family needs may also increase parental stress and strain parent-child relationships.[9]

As parents increase the family’s income, their children’s chances for better outcomes tick upwards. Increased income for parents is associated with a lower likelihood of child welfare investigations and child maltreatment, according to several research studies.[10] Children whose parents received a 50 percent boost in income achieved more academically as young children, attended school more regularly and were more likely to complete high school and college, according to researchers.[11]

Limited Education Keeps Parents in Low-Paying Jobs and Increases Poverty Risk for Children

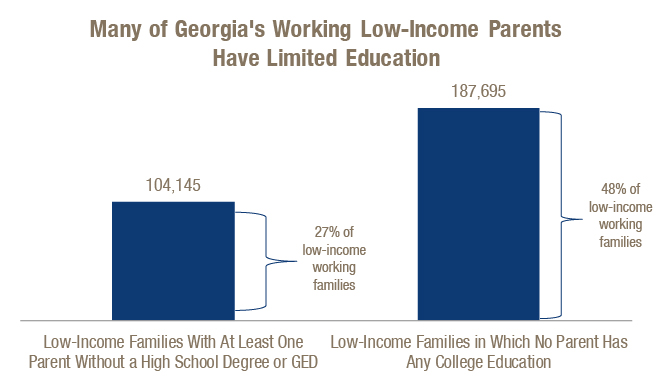

Many of Georgia’s working parents struggling with low incomes are trapped within their circumstances by limited education. In nearly 27 percent of Georgia’s low-income working families with children at least one parent lacks a high school diploma or its equivalent. And in nearly half of low-income working families, neither parent has education beyond high school.

Helping Georgians with low incomes to secure college credentials improves their earning potential. Workers with at least some progress toward an associate’s degree or a college credential earn an average of $31,750 per year in Georgia, compared to $26,802 for workers with only a high school diploma. Incomes jump to $49,696 per year on average for Georgians with bachelor’s degrees.

Increased access to higher education and training for Georgia parents reduces chances their families will live in poverty or beneath the low-income line. Families led by an adult with at least some college or an associate’s degree risk only a 13 percent chance of living in poverty. Families led by an adult without a high school diploma have a 31 percent chance of living in poverty.

Career Pathways: A Proven Route for Parents to Secure College Credentials and Boost Income

Georgia can look to the Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative as a way to help boost family income. That initiative is often cited by experts as a model to help parents with low incomes secure the credentials necessary to acquire and maintain jobs in high-wage, high-demand industries. The term career pathways is used nationwide to describe a series of connected education and training programs and support services that help people secure employment in a specific industry or occupation and advance to higher levels of related education and employment.[12] Support services include tuition, fees, books, child care, transportation and other support. Arkansas career pathways students are assigned a counselor trained to identify barriers people in poverty often face.[13]

Arkansans are eligible for career pathways if they are adult caretakers of children younger than 21 and current or former recipients of cash assistance from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. They are also eligible if they get food stamps, Medicaid or Arkansas’ children’s health insurance program. Arkansans are also eligible if they have annual income below 250 percent of the federal poverty line, or about $51,050 for a family of three in 2017.[14]

The Arkansas Career Pathways program achieved enviable success with roughly 30,000 parent participants since 2006. About 52 percent of students who participated in the program from 2006 to 2013 completed at least one higher education academic certificate or degree, compared to only 24 percent of community college students not participating in career pathways and enrolled in the same period.

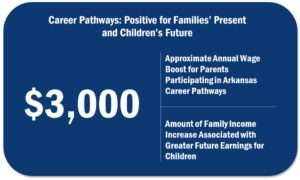

Career pathways students also earn more than public assistance recipients from the same areas of the state. Career pathways students earned on average $3,112 more in wages in their first 12 months after college than comparable public assistance recipients who did not participate in the program in 2011, the latest year data is available. The wage difference was even higher in the education and health services occupations. In 2011 career pathways graduates in these industries earned $3,176 more per year than public assistance recipients in the same location.[15]

Research shows a $3,000 boost to annual income for families with young children that earn less than $25,000 is associated with a 17 percent increase in adult earnings for children in those families. This $3,000 boost is also associated with 135 additional work hours per year for children after they reach age 25.[16]

Arkansas’ program also provides a significant return on investment. For every dollar invested in the program, the state receives $1.79 in benefits over five years through increased state taxes and reduced state spending on public assistance.[17]

Other examples of TANF-funded programs to help low-income adults secure college credentials can be found in Untapped Potential: Georgia Can Make Better Use of Federal Assistance for Workforce Development.

Career Pathways Can Also Help Georgia’s Economy

A career pathways program can also help Georgia strengthen its workforce and attract jobs. Georgia needs more workers with postsecondary credentials. More than 60 percent of Georgia’s jobs will require a certificate, associate’s degree or bachelor’s degree by 2025, according to the Governor’s Complete College Georgia initiative. Only 45 percent of the state’s young adults have one of those now and Georgia will need to produce an estimated 250,000 additional graduates beyond the expected graduation rate to meet its workforce needs. Educated adults will be crucial to Georgia’s 2025 workforce pipeline, according to the initiative.[18]

Career pathways can help close Georgia’s middle-skill gap. Middle-skill jobs require education beyond high school but less than a four-year degree. These jobs include nurses, welders and electricians. They account for 55 percent of Georgia’s labor market, but only 43 percent of the state’s workers are trained to do them.

Middle-skill jobs that require a certificate, associate’s degree or other postsecondary training will make up the majority of Georgia’s future jobs. Fifty-one percent of job openings between 2014 and 2024 are projected to require middle skills. Another 31 percent of job openings will require at least a four-year college degree, while only 18 percent of job openings will require no education beyond high school.[19]

How Georgia Can Establish Career Pathways

Georgia can follow Arkansas lead to establish a successful Career Pathways program. Georgia is already home to a highly regarded technical college system that can be used to deliver effective education and training to parents with low incomes.

Arkansas first laid the foundation for career pathways in 2005 with an $8 million award of TANF funding. The state picked 11 two-year colleges as pilot sites for the initiative based on the number of low-income parents in the service areas and the existence of an adult basic skills training program. Six of the sites ran pilots in fall 2005 enrolling more than 2,000 students. The other five sites joined the initiative in spring 2006. More than 3,300 enrolled students enrolled that year.[20] Arkansas granted each career pathways site about $500,000 during the first year. The colleges used the money to establish a career pathways office where workers coordinate program activities and provide guidance and support services for students.

Each Arkansas career pathways site conducted a gap analysis to determine where the education and training system needed improvement to meet employers’ needs. The colleges used the state’s labor market data to identify key industries in the community. Then pathways workers interviewed employers to ascertain skill needs. Career pathways counselors encourage students to target in-demand, well-paying occupations identified during the gap analysis.[21]

The federal government awards Georgia $331 million in TANF funding each year. Georgia can create a pilot modeled after Arkansas and account for its larger number of low-income families by investing an estimated $31 million in the initiative. A $31 million investment to launch career pathways represents only 9 percent of Georgia’s annual TANF funding allocation.[22] Georgia can conduct a smaller pilot to limit the initial expense.

Like Arkansas, Georgia can also open career pathways eligibility to any low-income person, regardless of whether they receive TANF cash assistance. This initial targeted investment can boost the wages of thousands of families with low incomes who are at greater risk of needing child welfare intervention, underachieving academically, poorer health and problem behaviors.

Conclusion: Georgia Can Provide a Better Future for Children Through Parents’ Education

Helping parents secure in-demand college credentials benefits Georgia’s families, its economy and the state budget. More parents with college credentials make it less likely families and children will struggle with poverty. Less pervasive poverty in Georgia is likely to reduce the number of families who interact with the child welfare system, easing pressure on the state’s child protection resources.

Georgia can begin by dedicating about 9 percent of the state’s annual allocation from the federal TANF grant to launch career pathways. This investment would not only improve incomes for Georgia families but also produce a significant return for the state.

Acknowledgements

This report is made possible by the generous support of the Working Poor Families Project, a national initiative funded by the Annie E Casey, Joyce and W.K. Kellogg foundations.

ENDNOTES

[1] Working Poor Families Project Analysis of Analysis of American Community Survey, 2015 (Washington, D.C. Population Reference Bureau). References to “working families” refers to families with children under 18. A family is defined as “working” if all family members ages 15 and older either had a combined work effort of 39 weeks or more in the prior 12 months, or all family members ages 15 and older have a combined work effort of 26 to 39 weeks in the prior 12 months and one currently unemployed parent looked for work in the prior four weeks. A “low income” for a family of three with one child is $38,636 per year.

[2] The term “career pathways” is used nationwide to represent “a series of connected education and training programs and support services that enable people to secure employment within a specific industry or occupational sector and to advance over time to successively higher levels of education and employment in that sector.” “Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative Progress/Close Out Reports of Activities and Outcomes,” Arkansas Department of Higher Education, July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016.

[3] Working Poor Families Project Analysis of Analysis of American Community Survey, 2015 (Washington, D.C. Population Reference Bureau).

[4] Joy Duva and Sania Metzger, “Addressing Poverty as a Major Risk Factor in Child Neglect: Promising Policy and Practice,” Protecting Children, American Humane Association, Volume 25, Number 1, P. 63, 2010.

[5] Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4) Report to Congress Executive Summary, January 2010.

[6] Joy Duva and Sania Metzger, “Addressing Poverty as a Major Risk Factor in Child Neglect: Promising Policy and Practice,” Protecting Children, American Humane Association, Volume 25, Number 1, P. 63, 2010.

[7] Jeffery Lubell, “Reviewing State Housing Policy with a Child-Centered Lens: Opportunities for Engagement and Intervention,” Center for Housing Policy, May 2013; Rebecca Cohen and Keith Waldrip, “Should I Stay or Should I Go? Exploring the Effects of Housing Instability and Mobility on Children,” February 2011.

[8] Julie Vogtman and Karen Schulman, “Set Up to Fail: When Low-Wage Work Jeopardizes Parents’ and Children’s Success,” National Women’s Law Center, January 2016. (citing Tamara Halle et al.., “Disparities in Early Learning and Development: Lessons from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort (ECLS-B)”, Child Trends, June 2009, http://ncfy.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/docs/18755-Disparities_in_Early_Learning_and_Development%5Bfull%5D.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2017.)

[9] Julie Vogtman and Karen Schulman, “Set Up to Fail: When Low-Wage Work Jeopardizes Parents’ and Children’s Success,” National Women’s Law Center, January 2016.

[10] Maria Cancian, Mi-Youn Yang, Kristen Shook-Slack, “The Effects of Additional Child Support Income on the Risk of Child Maltreatment,” Social Service Review, Vol. 87, No. 3, September 2013; Kerri M. Rassian and Lindsey Rose Bullinger, “Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates?,” Children and Youth Services Review Vol. 72, January 2017 (citing Berger, L. M., Font, S. A., Slack, K. S., & Waldfogel, J. “Income and Child Maltreatment: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Unpublished manuscript, School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin).

[11] Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson. “The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty,” Pathways, Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, Winter 2011.

[12] “Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative Progress/Close Out Reports of Activities and Outcomes,” Arkansas Department of Higher Education, July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016.

[13] Josh Bone, “TANF Education and Training: The Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative,” CLASP Center for Postsecondary and Economic Success, April 2010.

[14] “Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative Progress/Close Out Reports of Activities and Outcomes,” Arkansas Department of Higher Education, July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016.

[15] “The Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative: Phase One Research Results,” College Counts: Evidence of Impact, http://www.collegecounts.us/results/, Accessed May 11, 2017.

[16] Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson. “The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty,” Pathways, Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, Winter 2011.

[17] Brooke DeRenzis and Kermit Kaleba, “Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative: How TANF can support skills for low-income parents, and how policymakers can help,” National Skills Coalition, October 2016.

[18] “Georgia’s Higher Education Completion Plan 2012,” Complete College Georgia, November 2011. Complete College Georgia’s website (www.completegeorgia.org) reflects that over 60 percent of jobs in Georgia will require some form of a college education by 2025.

[19] “Georgia’s Forgotten Middle” National Skills Coalition, http://www.nationalskillscoalition.org/resources/publications/2017-middle-skills-fact-sheets/file/Georgia-MiddleSkills.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

[20] “Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative Progress/Close Out Reports of Activities and Outcomes,” Arkansas Department of Higher Education, July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016; Arkansas selected 11 two-year colleges as pilot sites for the initiative partly based on the number of “TANF-eligible” parents in their service areas. The state defines a “TANF-eligible” family as one who earns between 130 to 250 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2017, a family of three at 250 percent of the federal poverty level earns about $51,050 per year. Karen Rosa, “Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative,” Department of Higher Education, Arkansas Department of Workforce Services, Presentation to WIOA Panel, September 29, 2016.

[21] “Arkansas Career Pathways Initiative Progress/Close Out Reports of Activities and Outcomes,” Arkansas Department of Higher Education, July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016.

[22] The $31 million investment was calculated using Georgia’s and Arkansas’ numbers of low-income families with children. Georgia has roughly 3.1 times Arkansas’ number of low-income families with children. Working Poor Families Project Analysis of Analysis of American Community Survey, 2015 (Washington, D.C. Population Reference Bureau). The $31 million estimate assumes that Georgia’s budget for its career pathways pilot would be roughly 3.1 times larger than Arkansas’ $8 million budget for its pilot. The result of this multiplication was also adjusted for inflation since 2005 using the Consumer Price Index.