March 28, 2019 Update – The original voucher expansion bill, SB 173, failed on the Senate floor before Crossover Day. This week, as session winds down, the language was added as an amendment to HB 68 (LC 46 0162S), which had already passed the House. This puts a revised version of the voucher bill back in play between now and Sine Die, April 2. The revised language includes the following changes:

•All students who wish to participate must have been in public school the prior year

•Students eligible for participation are limited to students with special needs, students from families up to 150% of the poverty limit, children of active duty military parents, students adopted from foster care and students with a documented case of being bullied

•Enrollment in the voucher program will be frozen in any year that there is an austerity cut to QBE

•The voucher amount will be calculated with the five mill share deduction made as well as any other cuts to funding going to districts for their students

•After graduation, funds rolled over from previous years cannot be used for postsecondary expenses. Remaining funds are returned to the state general fund.

•The program cap was changed from 5% to 2.5% statewide and a 2.5% cap per district.

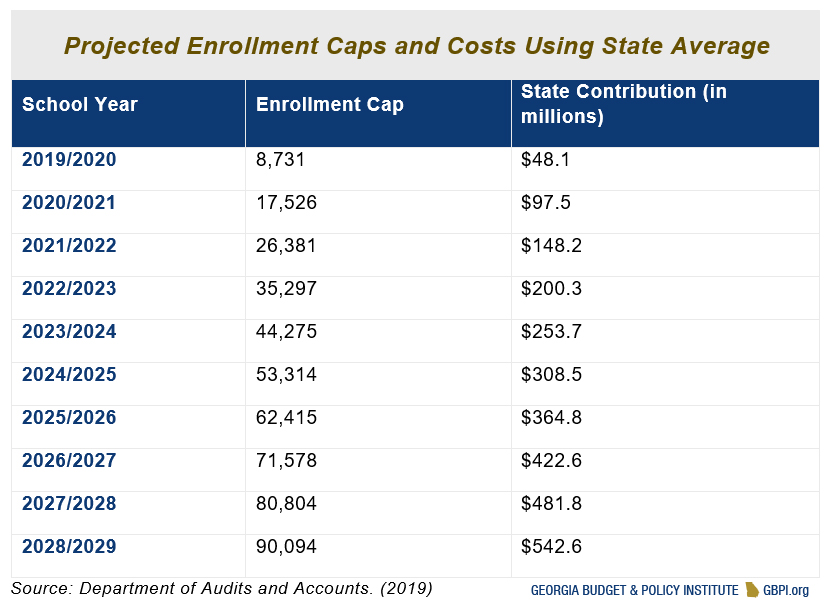

The lowered enrollment cap would mean that the state diverts a total of $253.7 million annually from public to private education programs upon full implementation. The total cost of administration is $8.2 million annually with these changes.

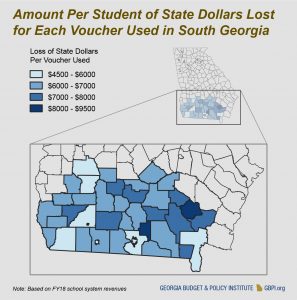

March 6, 2019 Update: Further analysis shows the vouchers would disproportionately  hurt South Georgia counties as illustrated in the map below. The state spent an average of $5,426 per student in FY18. Some of the South Georgia districts would lose more than $8,000 per student if they took a voucher.”

hurt South Georgia counties as illustrated in the map below. The state spent an average of $5,426 per student in FY18. Some of the South Georgia districts would lose more than $8,000 per student if they took a voucher.”

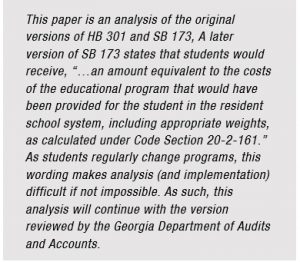

Georgia lawmakers offered two bills that divert public money to private schools. House Bill 301 and Senate Bill 173 are identical bills that use state money meant for public schools to pay for private school tuition or education service providers. This analysis looks at the potential costs and other considerations that may better serve Georgia’s students.

Georgia lawmakers offered two bills that divert public money to private schools. House Bill 301 and Senate Bill 173 are identical bills that use state money meant for public schools to pay for private school tuition or education service providers. This analysis looks at the potential costs and other considerations that may better serve Georgia’s students.

Both HB 301 and SB 173 establish so-called “educational scholarship accounts” to pay for qualified education expenses including but not limited to: private school tuition, tutoring and transportation. The amount of these vouchers varies based on whether the student has an Individualized Education Program (IEP) and where they live. The state would give students with an IEP the amount equal to the cost paid had they stayed in their local public schools, less any federal dollars. The state would provide all other participants the average amount that the state pays to that student’s resident school system.

Potential Costs

Both bills begin by capping participation in the vouchers at 0.5 percent of 2018-2019 public school student enrollment, or about 8,700 students. This enrollment cap increases by 0.5 percentage points every year until reaching a hard cap of 5 percent. In its first year, the state would redirect a projected $48 million away from public schools, based on 2019 average per-student state spending of $5,500. Once fully implemented the school vouchers would cost a projected $543 million per year.

The legislation authorizes the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement (GOSA) to implement and distribute the vouchers. Both bills allot up to 3 percent of the voucher cost for administration, at a projected annual fee of $16.3 million. The actual cost of vouchers also depends on the participating child’s IEP status. Those with an IEP would likely receive state funding higher than the average expenditure. Any funding provided from the federal level would be forfeited.

Vouchers as A Failed Policy

Vouchers are consistently associated with lower test scores for participating students. Recent studies from Louisiana[1], Ohio[2], Washington D.C.[3] and Indiana[4] show student performance suffers for students who change from public to private schools. These results counter the widespread belief that private school education is a wholesale improvement on public schooling. Voucher studies suggest that performance differences between public and private school students can be explained by factors like students’ family incomes, not because private education is inherently better.[5]

Lower test scores are not the only legacy of school vouchers. In Arizona, the state’s Attorney General audited the state voucher system and found “persistent” misuse of funds year after year.[6] In one year alone, the state found fraudulent purchases totaling over $700,000 on things like beauty supplies and athletic apparel. Furthermore, parents of students with disabilities are often unaware that acceptance of these vouchers waives pivotal federal protections for their children. Private schools are often not held to certain requirements dealing with due process or “least restrictive environment.”[7] These red flags make this program unworthy of significant state investment.

Considerations

State legislators would be wise to use the redeemable portions of this bill in other education policies around the state. Georgia already has a large pot of money that can be used for private school tuition, the Qualified Education Expenses Tax Credit (QEETC). Lawmakers expanded the cap for this voucher program in the 2018 General Assembly from $58 million to $100 million. Unlike the proposed bills discussed in this analysis, the QEETC does not have any testing requirements for the participating students. Requiring students to take state-mandated tests would offer Georgians an opportunity to see what, if any, return taxpayers are getting on the tax credit.

One year after Georgia fully funded public schools, the state should not put itself in a position to undercut these gains. School districts are in the process of undoing the damage done by austerity cuts of more than $9 billion over the last 16 years. Vouchers encourage student enrollment decline and hinder a school’s ability to provide the same education to remaining students. Instead of diverting money away from Georgia’s public schools, lawmakers should continue to support the state’s obligation to provide an adequate public education.

[1] Abdulkadiroğlu, A., Pathak, P. A., & Walters, C. R. (2018). Free to choose: can school choice reduce student achievement? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1), 175-206.

[2] Figlio, D., & Karbownik, K. (2016). Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program: Selection, Competition, and Performance Effects. Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

[3] Dynarski, M., Rui, N., Webber, A., & Gutmann, B. (2017). Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts after One Year. NCEE 2017-4022. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

[4] Waddington, R. J., & Berends, M. (2018). Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement effects for students in upper elementary and middle school. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(4), 783-808.

[5] Lubienski, C. A., & Lubienski, S. T. (2013). The public school advantage: Why public schools outperform private schools. University of Chicago Press.

[6] Perry, L. (2018). Arizona Department of Education: Empowerment Scholarship Accounts Program. Auditor General Report No. 16-107 24-Month Follow-up Report. Retrieved from: https://www.azauditor.gov/system/tdf/16-107_24Mo_Followup.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=9096&force=0

[7] National Council on Disability. (2018). School Choice Series: Choice & Vouchers-Implications for Students with Disabilities. Retrieved from: https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Choice-Vouchers_508_0.pdf