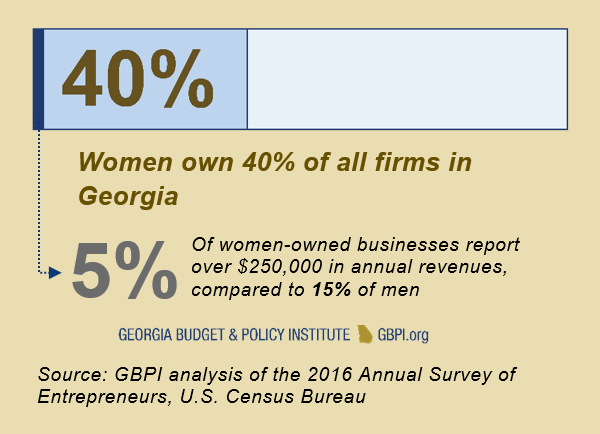

Georgia ranks second in the nation for the growth of women-owned businesses.[1] Women own about 40 percent of Georgia firms.[2] Entrepreneurship remains a powerful way for women to propel themselves along the path to economic prosperity. Still, while the number of women business owners is growing fast in Georgia, they lag significantly behind men in access to capital and the generation of new revenue. This disparity limits the potential of women-owned businesses to develop infrastructure, hire new employees and seize the promising potential of entrepreneurship as a means to build wealth for themselves and their communities. The lack of targeted strategies to correct this disparity worsens gender equity, hinders economic inclusion and threatens the strength of Georgia’s economy.

Georgia ranks second in the nation for the growth of women-owned businesses.[1] Women own about 40 percent of Georgia firms.[2] Entrepreneurship remains a powerful way for women to propel themselves along the path to economic prosperity. Still, while the number of women business owners is growing fast in Georgia, they lag significantly behind men in access to capital and the generation of new revenue. This disparity limits the potential of women-owned businesses to develop infrastructure, hire new employees and seize the promising potential of entrepreneurship as a means to build wealth for themselves and their communities. The lack of targeted strategies to correct this disparity worsens gender equity, hinders economic inclusion and threatens the strength of Georgia’s economy.

This analysis builds on 2017’s “Laying the Foundation: A Wealth-Building Agenda for Georgia Women”, a GBPI report that details a comprehensive set of policies to give women more ways to achieve prosperity and support their families.[3] This update expands on the recommendations to boost women’s entrepreneurship in Georgia.

Supporting business owners and innovators is a foundational pillar that builds economic opportunity and closes Georgia’s gender and racial wealth divide. The state can pursue two practical strategies to promote and improve access to entrepreneurial pathways for women:

- Leverage the state government’s immense purchasing power and target women as contractors

- Increase targeted technical assistance and capital for immigrant women entrepreneurs

Why is the Women’s Wealth Gap a Threat to Georgia’s Future Prosperity?

Although the majority of Georgia’s breadwinners are women, their opportunities to build wealth are often limited. Obstacles to wealth-building include flat wages, gender discrimination and too few paths to help women accumulate assets and sustain themselves and their families for future generations.

Discussions of economic inequality often focus solely on wages to quantify the financial disparities between men and women. However overall personal or family wealth measured as the sum of a person’s assets minus their debts is just as important.[4] It typically includes a household’s bank accounts, retirement savings, valuable heirlooms, stocks and equity in a home or business.

Wealth serves as a critical buffer when individuals and families suffer abrupt financial downturns. Many low-income women and their families find it almost impossible to save. In Georgia, 43.9 percent of households lack sufficient savings to cover three months of expenses due to lost income or unexpected medical bills.[5] While most women are primary workers, lower wages due to pervasive gender discrimination, limited options for paid family leave and the rising costs of housing, child care and health care strain their savings and earnings potential.

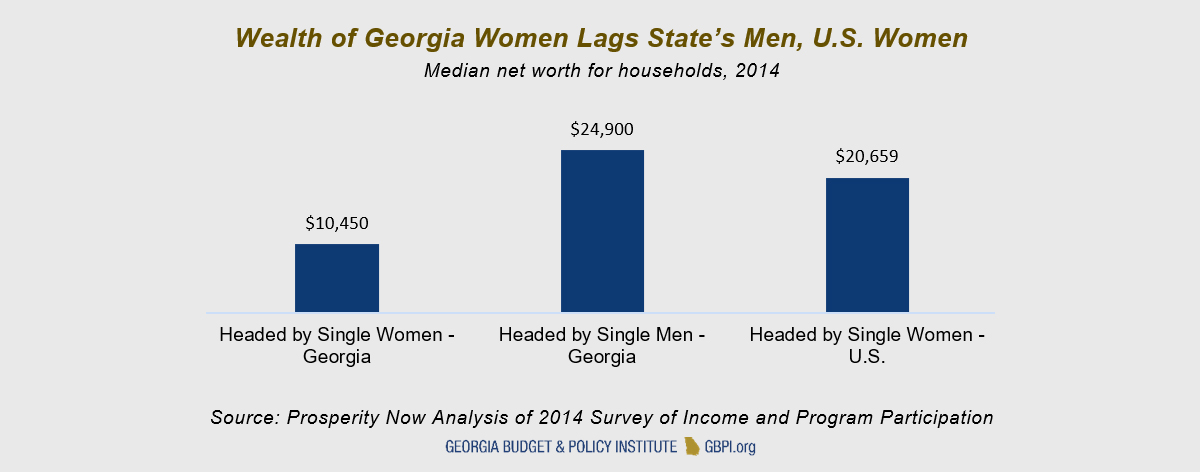

More investment in wealth-building strategies can help Georgia maximize the potential of its women to support their families and boost the state’s economy. Households headed by a single woman only hold about $10,450 in wealth, compared to $24,900 for single men.[6]

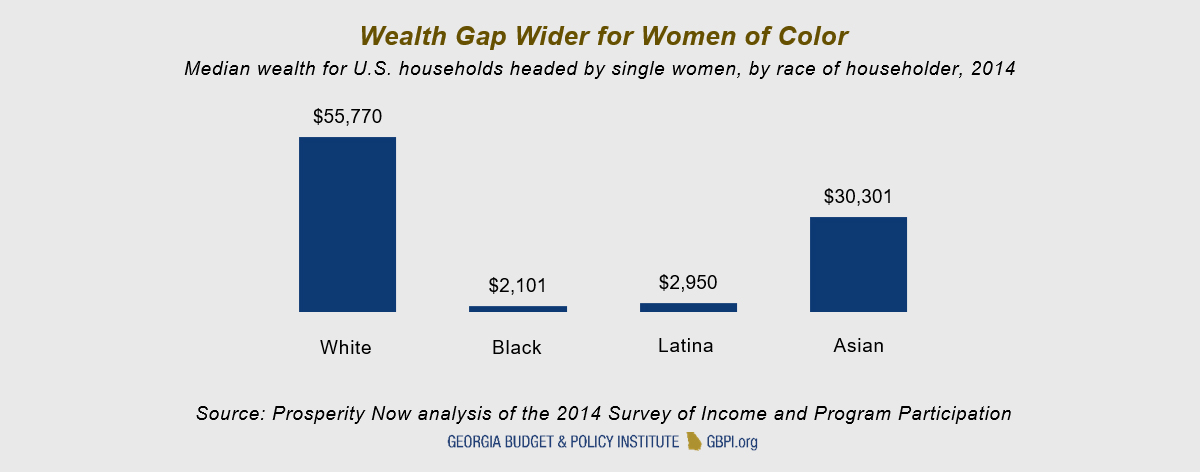

Wealth disparities are even more glaring for women of color due to the dual role of systemic racial and gender bias. The typical wealth for a U.S. household headed by a single white woman is $55,770. This compares to just $2,101 for households headed by a single black woman, $2,950 for those headed by a single Latino woman, and $30,301 for those headed by a single Asian woman.[7]

Wealth disparities are even more glaring for women of color due to the dual role of systemic racial and gender bias. The typical wealth for a U.S. household headed by a single white woman is $55,770. This compares to just $2,101 for households headed by a single black woman, $2,950 for those headed by a single Latino woman, and $30,301 for those headed by a single Asian woman.[7]

It is important to Georgia’s future prosperity that roadblocks to building wealth for people of color are eliminated, particularly since they are due to become the majority of the state’s population by 2030.[8] Policy decisions that do not weigh racial equity as a factor often reinforce disparities that exist among black, Latino and white Georgians as seen in measures in high school graduation rates, college completion, access to jobs and earnings.

It is important to Georgia’s future prosperity that roadblocks to building wealth for people of color are eliminated, particularly since they are due to become the majority of the state’s population by 2030.[8] Policy decisions that do not weigh racial equity as a factor often reinforce disparities that exist among black, Latino and white Georgians as seen in measures in high school graduation rates, college completion, access to jobs and earnings.

Georgia can improve its policies to give more access to business ownership and close the wealth divide between women and men. Ensuring women get both sufficient opportunities and the means to start successful new businesses at the same rate as men is critical to the state’s long-term economic health.

Business Ownership is a Key Wealth-Building Strategy

Entrepreneurship clears a path to wealth through business ownership. It offers the opportunity to improve the financial security of individual entrepreneurs and also boost the economic vitality of entire communities. Entrepreneurship is an on-ramp to community-wide wealth-building well beyond individual business owners’ gain. For example, new firms and young businesses account for about 70 percent of overall U.S. job creation.[9]

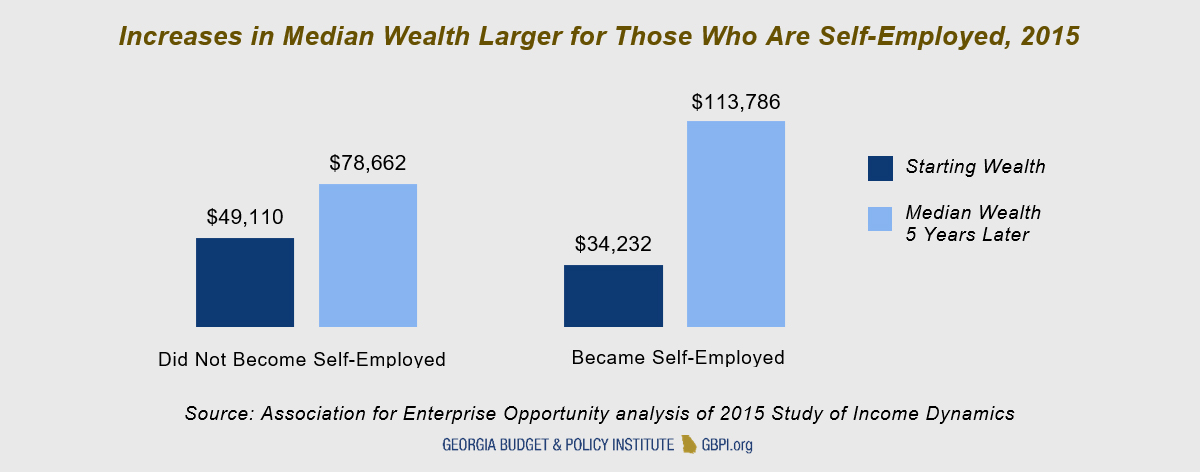

People who own businesses tend to create more wealth. Increases in median wealth are larger over a five-year period for people who are self-employed compared to those who are not.[10]

The variation in wealth between people who start businesses and those who do not is not necessarily tied to who starts with more wealth and assets.

The variation in wealth between people who start businesses and those who do not is not necessarily tied to who starts with more wealth and assets.

Business ownership is a meaningful way for low-income single women to build wealth. That is especially true for women who care for children or other family members. Women disproportionately head single households. Nearly 556,000 Georgia households are headed by single mothers.[11] Wage-constrained employment opportunities combined with family responsibilities among low-income women make business ownership a promising pathway to a better financial future. Women entrepreneurs are more likely than men to turn to business ownership to accommodate for family responsibilities such as child care. One of the top reasons women report wanting to own a business is to “balance work and family”.[12]

Business ownership is a meaningful way for low-income single women to build wealth. That is especially true for women who care for children or other family members. Women disproportionately head single households. Nearly 556,000 Georgia households are headed by single mothers.[11] Wage-constrained employment opportunities combined with family responsibilities among low-income women make business ownership a promising pathway to a better financial future. Women entrepreneurs are more likely than men to turn to business ownership to accommodate for family responsibilities such as child care. One of the top reasons women report wanting to own a business is to “balance work and family”.[12]

Business ownership is also a powerful means for women to achieve economic mobility. It provides women with financial security through self-employment, which allows a long-term source of support for themselves and their families. Sixty percent of the increase in employment for women from 2009 to 2012 was in 10 of the lowest wage occupations.[13] The median hourly wage of women-owned business employees is $15.79[14], which shows ownership can help buck the trend of minimum wage work.

Women’s Entrepreneurship on the Rise in Georgia and U.S.

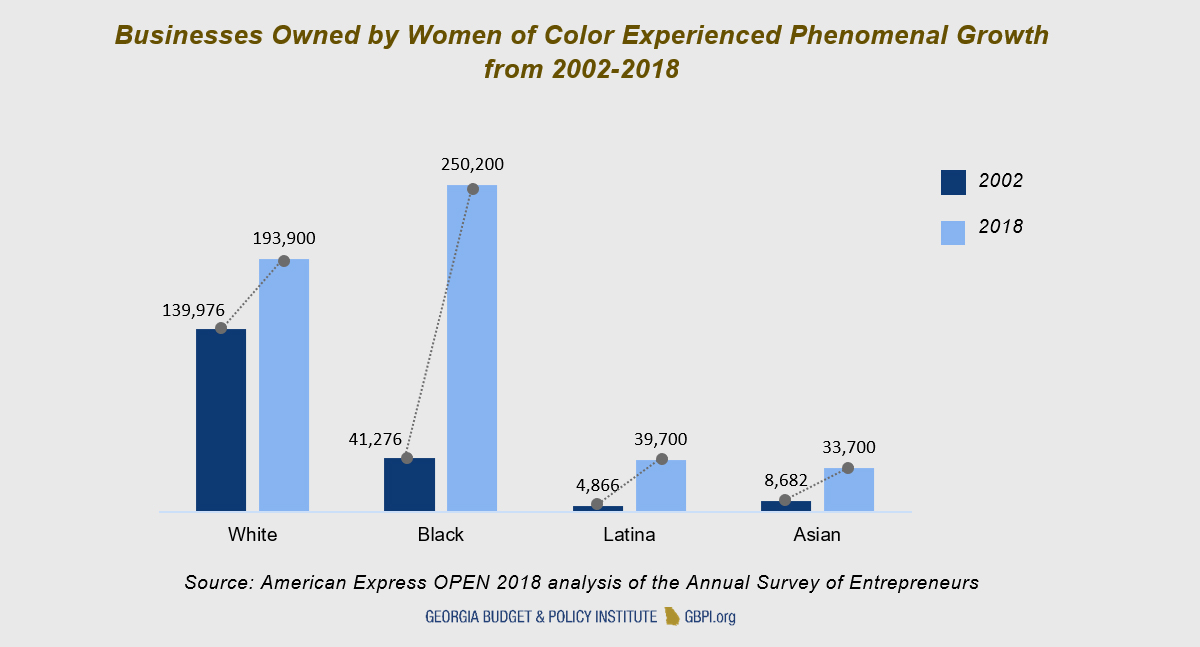

From 2002 to 2018, women started about 124 new firms per day. Women of color are the driving force behind the growth in business ownership. The number of firms owned by black women grew to 250,000 in 2018 from 41,276 in 2002.[15]

Despite their growing role as business owners, women lag behind their male counterparts when it comes to new revenue generation which limits the potential of these businesses to expand and create new jobs. Only 5 percent of Georgia’s women-owned businesses report more than $250,000 in annual revenue compared to 15 percent of those owned by men.[16]

Despite their growing role as business owners, women lag behind their male counterparts when it comes to new revenue generation which limits the potential of these businesses to expand and create new jobs. Only 5 percent of Georgia’s women-owned businesses report more than $250,000 in annual revenue compared to 15 percent of those owned by men.[16]

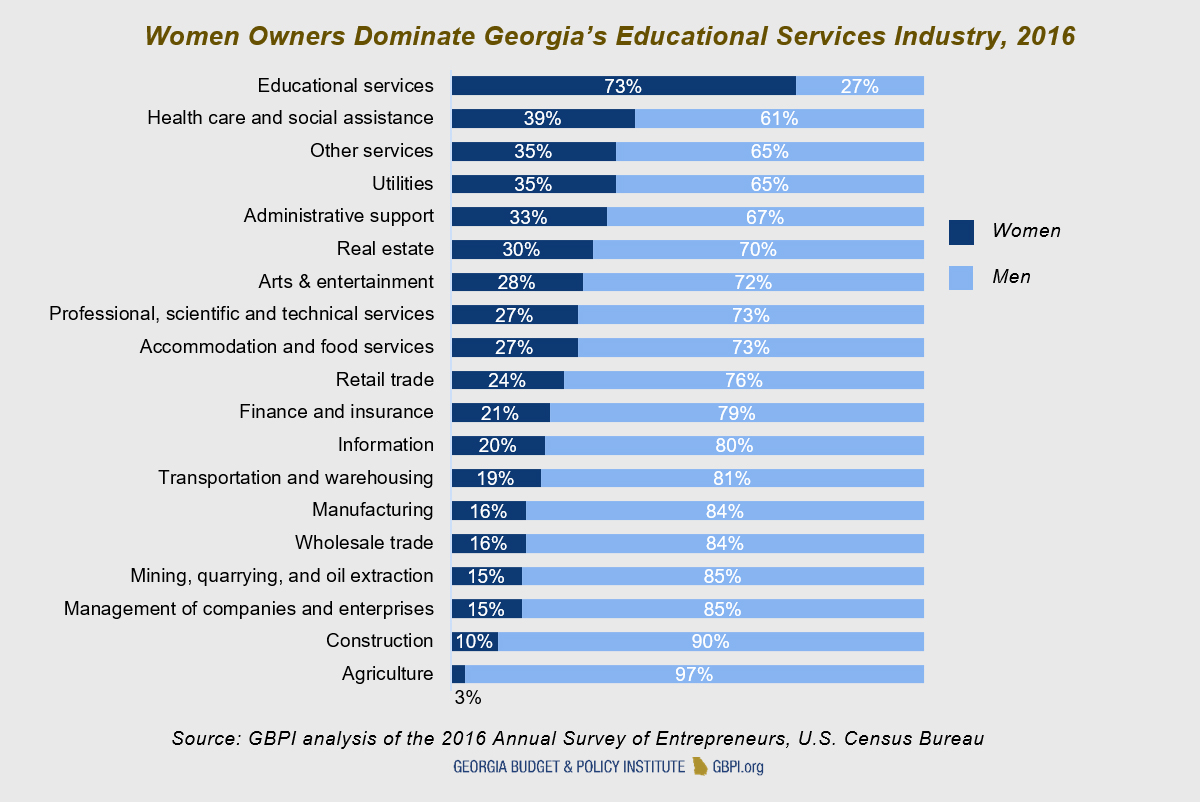

Georgia women tend to own companies in lower-revenue industries. The top industry for women-owned businesses is educational services. Other common industries include personal care, laundry, health care and social assistance. The top industries for men-owned businesses are construction and professional, scientific and technical services.

Georgia women tend to own companies in lower-revenue industries. The top industry for women-owned businesses is educational services. Other common industries include personal care, laundry, health care and social assistance. The top industries for men-owned businesses are construction and professional, scientific and technical services.

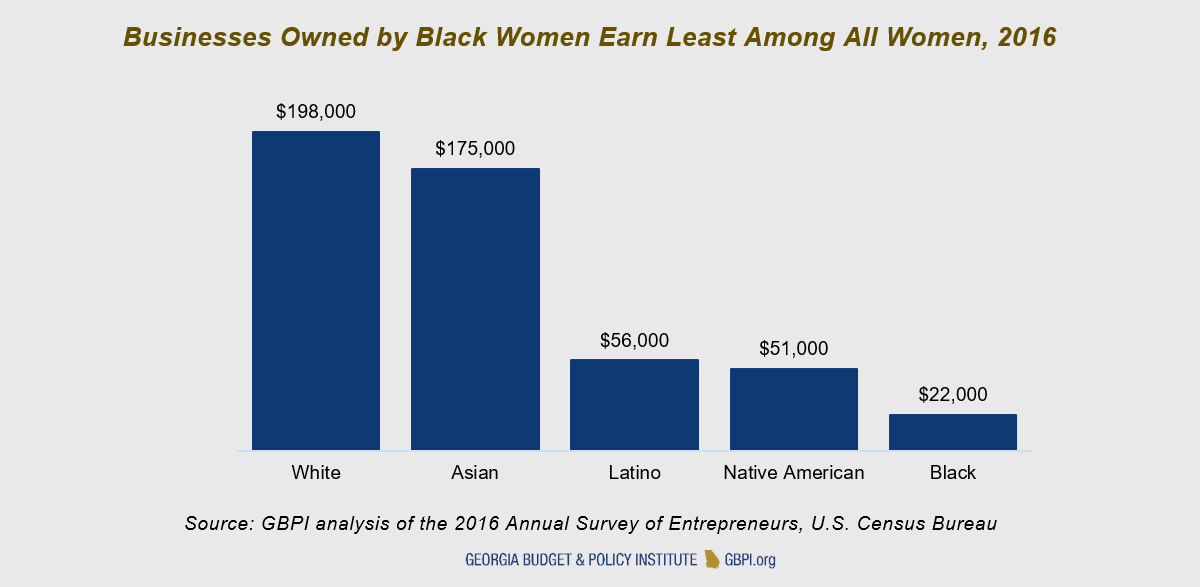

Women of color own more businesses than white women in Georgia, yet their revenues are lower. Georgia’s business owned by white women reported an average of $198,000 in annual revenues, compared to just $22,000 for black women and $56,000 for Latinas. And just two percent of Georgia businesses owned by black women employ paid staff, compared to 13 percent for firms owned by white women.[17]

Women of color own more businesses than white women in Georgia, yet their revenues are lower. Georgia’s business owned by white women reported an average of $198,000 in annual revenues, compared to just $22,000 for black women and $56,000 for Latinas. And just two percent of Georgia businesses owned by black women employ paid staff, compared to 13 percent for firms owned by white women.[17]

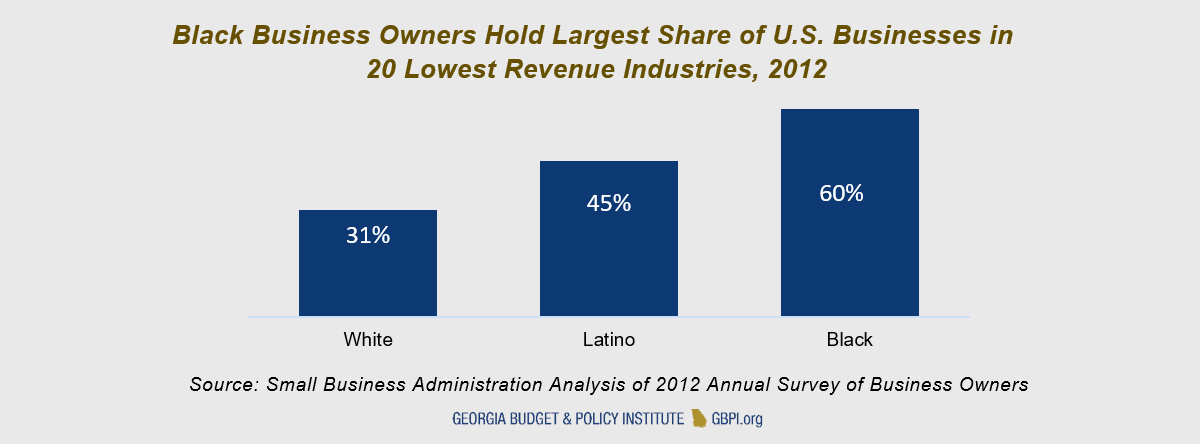

The different kinds of products and services these firms provide help explain the revenue among racial and ethnic groups. Nearly 60 percent of all black-owned businesses in the country are in the 20 lowest sales-generating industries. Nearly 45 percent of Latino businesses are also in these industries while just 31 percent of white-owned businesses are in the low-sales category.

The different kinds of products and services these firms provide help explain the revenue among racial and ethnic groups. Nearly 60 percent of all black-owned businesses in the country are in the 20 lowest sales-generating industries. Nearly 45 percent of Latino businesses are also in these industries while just 31 percent of white-owned businesses are in the low-sales category.

Women Struggle to Gain Access to Capital

Women Struggle to Gain Access to Capital

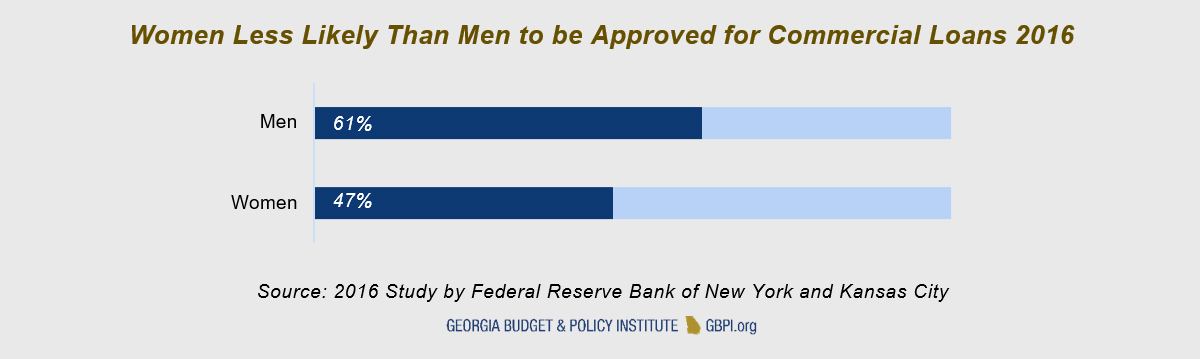

Women open businesses with about half as much capital as men and struggle to borrow additional money.[18] Access to capital is key to successful business ownership. The amount of startup money an entrepreneur has available for a business launch often determines its future success. Barriers to gaining capital is an ongoing challenge for women entrepreneurs. Fewer than half of applications women business owners submitted for commercial business loans in 2016 were approved.[19] Financing shortfalls underpinned by gender biases derail women from growing and sustaining their own businesses.

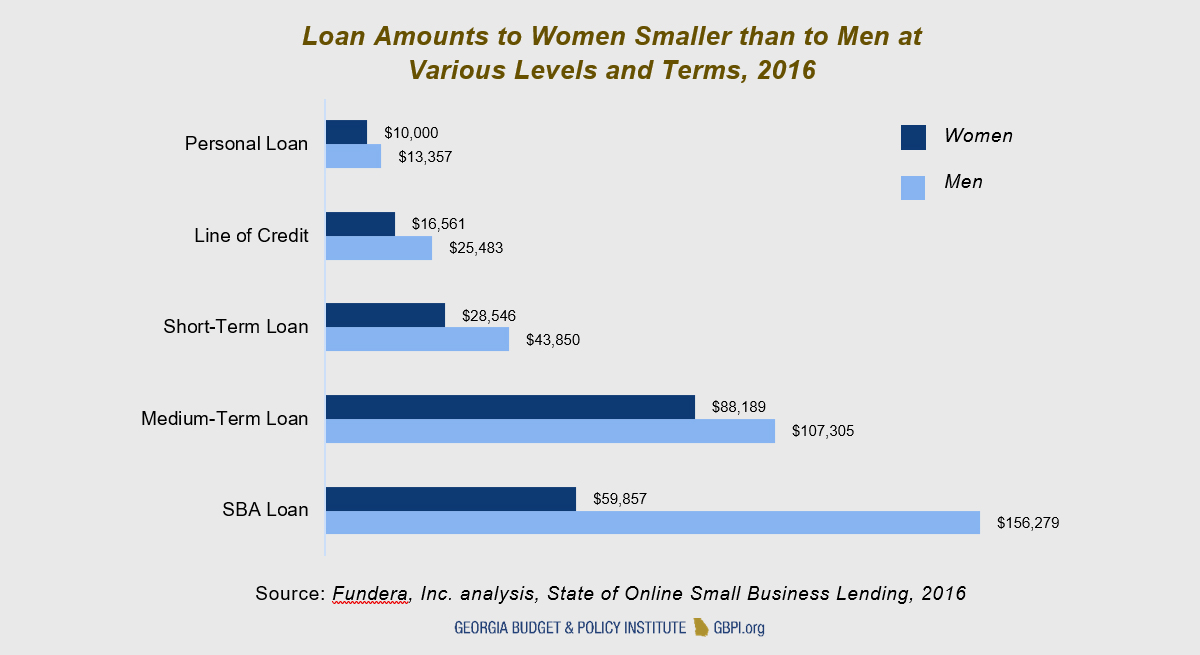

Women are about as likely to be approved for government-backed U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) loans as men. Still, the SBA loan program awards women an average of 2.5 times less than men. In both the private and SBA markets, women are also awarded smaller loans than men.[20]

Women are about as likely to be approved for government-backed U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) loans as men. Still, the SBA loan program awards women an average of 2.5 times less than men. In both the private and SBA markets, women are also awarded smaller loans than men.[20]

The troubling tendency to underfund women-owned startups extends to venture capitalists. Those investors handed $85 billion to U.S. businesses in 2017 and just $1.9 billion of that went to women entrepreneurs.[21] Venture capital is an important source for startup businesses, especially in technology and other industries traditionally dominated by men.

The troubling tendency to underfund women-owned startups extends to venture capitalists. Those investors handed $85 billion to U.S. businesses in 2017 and just $1.9 billion of that went to women entrepreneurs.[21] Venture capital is an important source for startup businesses, especially in technology and other industries traditionally dominated by men.

Women are often unable to tap capital due to harmful gender-based stereotypes, along with less consistent credit and income history as a result of job discrimination and wage inequality. A lack of access to safe and affordable banking products creates yet another obstacle.

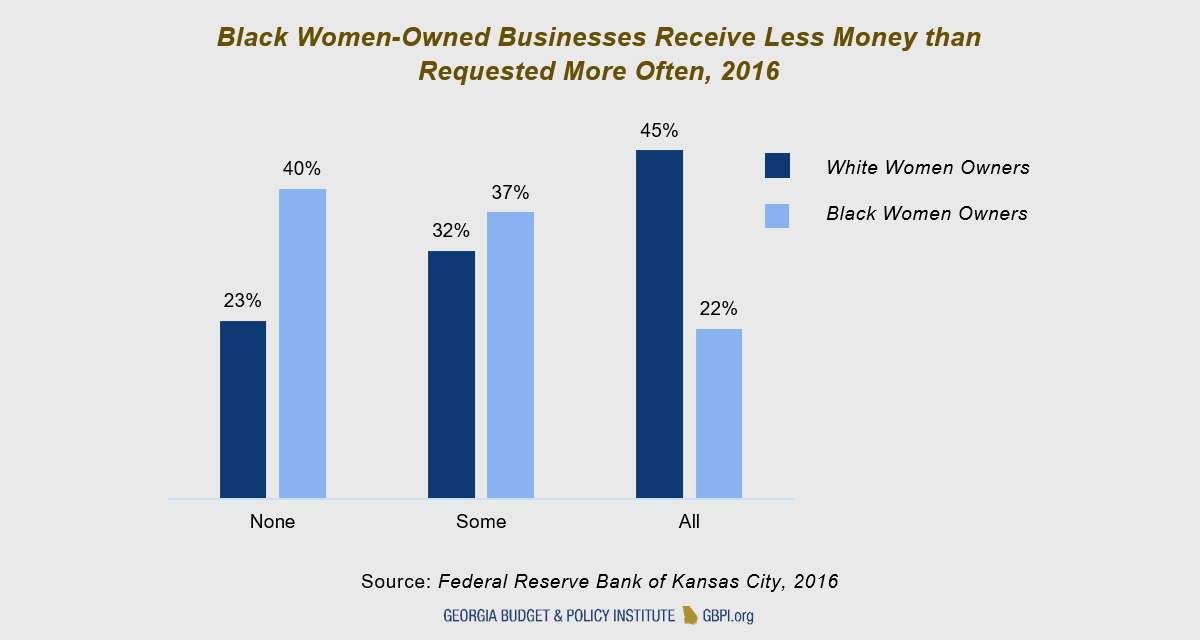

Women entrepreneurs who are black or Latina are denied loans at even higher rates. Even when controlling for differences in creditworthiness, black and Latina business owners tend to pay higher interest rates than white business owners and are likelier to be denied business loans.[22] Black women are even less likely to obtain business capital than the general population of business owners, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City survey.[23] Just 22 percent of black women entrepreneurs in the survey say they raised all the capital they needed, compared to 45 percent of white women respondents.[24]

Financing is key to starting and growing a business, so these gaps in access to capital create major barriers for women entrepreneurs, which in turn hinders the ability to generate jobs and economic impact. The lag in capital access translates to much smaller bottom lines for women-owned businesses when compared to men. As a result, household and personal wealth for women entrepreneurs doesn’t reach its potential and the community gets fewer jobs.

Financing is key to starting and growing a business, so these gaps in access to capital create major barriers for women entrepreneurs, which in turn hinders the ability to generate jobs and economic impact. The lag in capital access translates to much smaller bottom lines for women-owned businesses when compared to men. As a result, household and personal wealth for women entrepreneurs doesn’t reach its potential and the community gets fewer jobs.

Help Women Build Wealth through Contracting Goals, Technical Assistance

Georgia can eliminate systemic barriers that perpetuate and limit opportunities for women to grow wealth by implementing targeted efforts to support women-owned businesses. State lawmakers can seize this moment to keep Georgia positioned as the number one place in the country to do business while also becoming a national leader in economic inclusion. Two key strategies to make this happen are to:

- Leverage the state government’s immense purchasing power and target women as contractors

- Increase targeted technical assistance and capital for immigrant women entrepreneurs

Georgia Can Increase Gender Equity through State Contracting Goals

Including more women in state contracting is one promising way to increase their access to business ownership and employment. Federal, state and local governments are major purchasers of business services and products. Businesses owned solely by women historically had limited opportunities to compete for government contracts due to conscious and systemic discrimination. Georgia can advance women-owned businesses with new goals for state contracting relationships in all of its state agencies, from public safety to colleges and universities. Georgia buys more than $4.5 billion in goods and services each year and a fair distribution of that spending can provide a huge lift to ensure more women-owned businesses grow in the mainstream economy and create jobs.[25]

Georgia’s minority business certification program is now designed to help increase the visibility of businesses owned by people of color. Georgia corporations can also earn a tax credit for payments made to subcontractors certified as minority businesses. The state’s minority business certification does not include women.[26] There are also no goals to contract with women and people of color across all state agencies. Georgia also does not publicly report how much business it does with women and people of color across all agencies either.

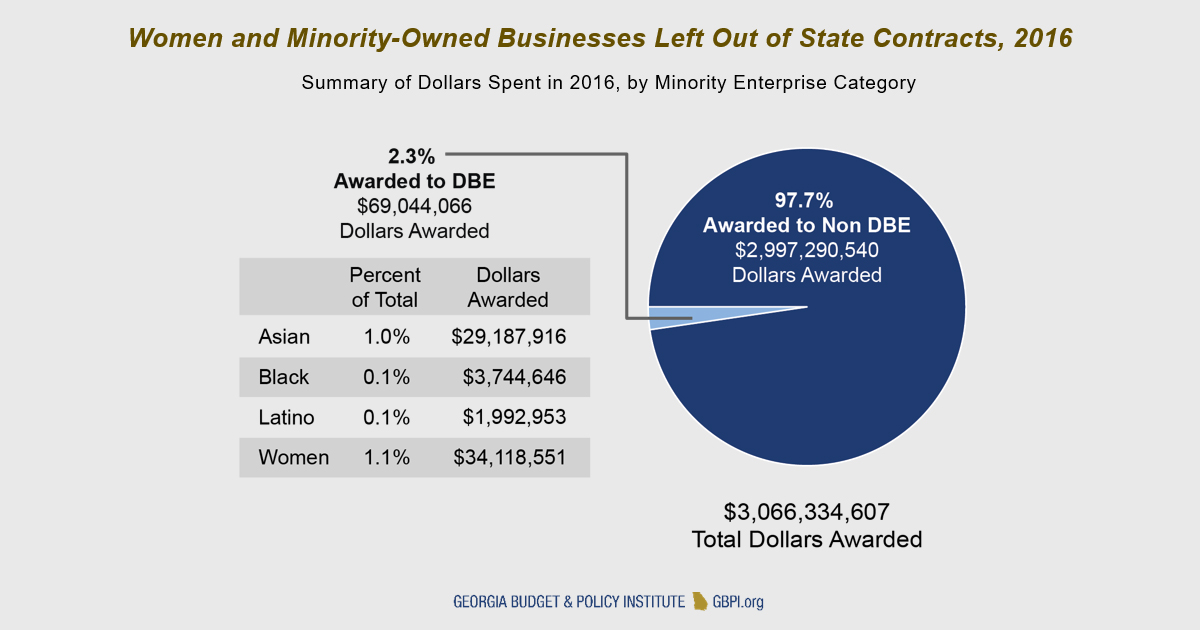

The federal Disadvantaged-Business Enterprise program operated by the U.S. Department of Transportation requires that Georgia undergoes an inclusive contracting procedure. Georgia must operate an enterprise program within its transportation department to get federal money, which amounted to $1.6 billion in the 2018. Just one percent of money the Georgia Department of Transportation spent in 2016 went to women-owned prime contractors.[27] This falls well below even the modest federal efforts to target women-owned businesses. According to the SBA, only 5 percent of federal procurement contracts are awarded to women-owned businesses.[28]

The state transportation department now uses race- and gender-neutral strategies to encourage underrepresented contractors to participate in the bid process.[29] A contractor is selected solely on the basis of the lowest bid without regard to enterprise program status. This approach hurts the chances of small and mid-sized businesses to win contracts against larger, better connected businesses. These programs can help increase opportunities for businesses owned by women and people of color, but outcomes are likely to be poorer than racial- or gender-explicit policies that set contracting goals specifically for women and people of color.[30]

The state transportation department now uses race- and gender-neutral strategies to encourage underrepresented contractors to participate in the bid process.[29] A contractor is selected solely on the basis of the lowest bid without regard to enterprise program status. This approach hurts the chances of small and mid-sized businesses to win contracts against larger, better connected businesses. These programs can help increase opportunities for businesses owned by women and people of color, but outcomes are likely to be poorer than racial- or gender-explicit policies that set contracting goals specifically for women and people of color.[30]

As a state, Georgia can learn from Maryland’s model. Lawmakers there aim to deliver 29 percent of all state contracts to minority and women-owned businesses. Maryland awarded about $2.3 billion, or 26.2 percent, of its procurement to businesses owned by women and people of color in 2015, according to the most recent available data. The strategy generated 22,128 jobs, $917 million in wages and about $67.4 million in state and local tax receipts in 2014.[31]

Georgia lawmakers proposed in 2019 to establish a division of supplier diversity in its Department of Administrative Services. The legislation aimed to increase the amount of minority and women-owned contractors in the state procurement process through the creation of this new division. The legislation didn’t pass before the General Assembly adjourned.

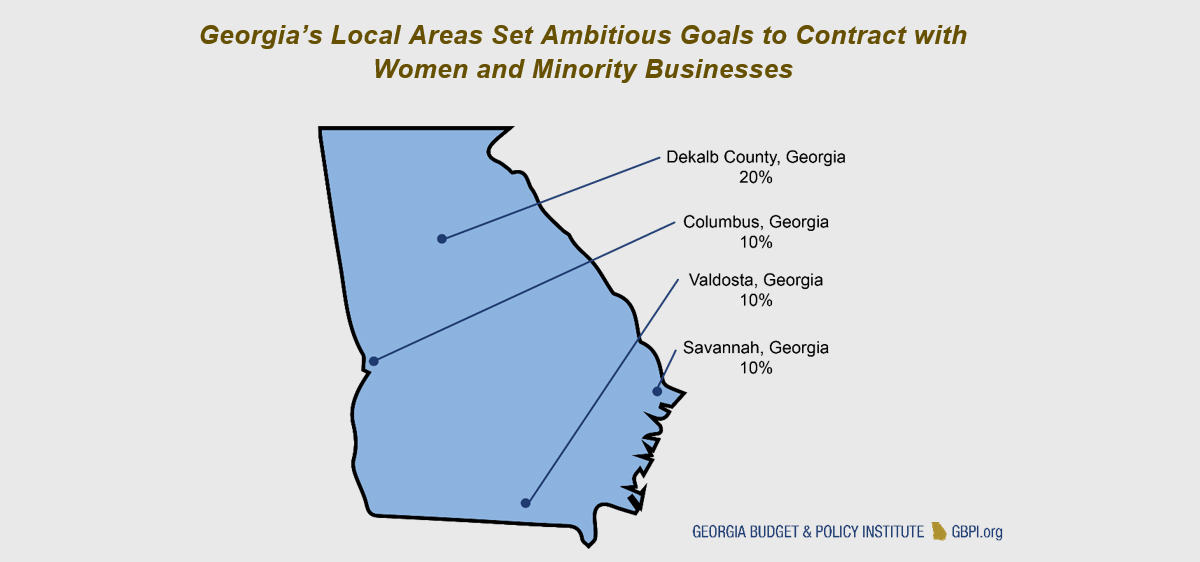

Despite the state’s lack of explicit and robust participation goals, municipalities are leading in inclusive procurement for women who own small businesses. Atlanta, Georgia is well-known for its inclusive contracting goals, especially for women- and minority-owned firms. According to a study by Colorado-based Keen Research, 40 percent of contracts with stated goals went to minority- and women-owned businesses. Based on data for $4 million of contracts with goals for small businesses for 2013 and 2014, 79 percent of those dollars went to minority- and women-owned firms.[32]

Other examples of cities and counties with stated goals for small, minority and women-owned businesses in their local code ordinances are in the chart below[33]:

Improve Equity with Targeted Technical Assistance and Capital for Immigrant Entrepreneurs

Improve Equity with Targeted Technical Assistance and Capital for Immigrant Entrepreneurs

Immigrant entrepreneurs offer strong economic growth potential, but they are often overlooked in programs intended to strengthen small business in Georgia. Sure, the state offers technical assistance to small businesses through a number of agencies and programs. What’s lacking is targeted outreach and support specific to businesses owned by immigrants.[34]

Georgia can seize a huge opportunity by giving immigrant women entrepreneurs more support. Immigrants are more likely than native-born Americans to start businesses.[35] Immigrants make up 31 percent of Georgia’s Main Street business owners, despite accounting for only 10 percent of the state’s population. Georgia can build on that success with more inclusive contracting targets and programming to leverage the state’s growing base of immigrant entrepreneurs. Georgia experienced the most rapid growth of Latina-owned business in the country from 2007 to 2018.[36] About 60 percent of Georgia’s Latinas are immigrants. Access to Capital for Entrepreneurs and the Latin American Association[37] are two Georgia-based organizations leading the way by providing capital and dual language business planning curricula to Latinas and immigrants. The Latin American Association helped more than 400 low-income Hispanic women launch small businesses. The Refugee Women’s Network in Georgia also provides microloans and training to refugee[38] women of color resettling in Georgia.[39] The state can partner with these efforts to build on the phenomenal growth of businesses owned by newcomers while specifically increasing the wealth of women.

Georgia can seize a huge opportunity by giving immigrant women entrepreneurs more support. Immigrants are more likely than native-born Americans to start businesses.[35] Immigrants make up 31 percent of Georgia’s Main Street business owners, despite accounting for only 10 percent of the state’s population. Georgia can build on that success with more inclusive contracting targets and programming to leverage the state’s growing base of immigrant entrepreneurs. Georgia experienced the most rapid growth of Latina-owned business in the country from 2007 to 2018.[36] About 60 percent of Georgia’s Latinas are immigrants. Access to Capital for Entrepreneurs and the Latin American Association[37] are two Georgia-based organizations leading the way by providing capital and dual language business planning curricula to Latinas and immigrants. The Latin American Association helped more than 400 low-income Hispanic women launch small businesses. The Refugee Women’s Network in Georgia also provides microloans and training to refugee[38] women of color resettling in Georgia.[39] The state can partner with these efforts to build on the phenomenal growth of businesses owned by newcomers while specifically increasing the wealth of women.

Conclusion

Uneven access to capital and contracting opportunities for women business owners are among the steepest barriers they must overcome to build wealth and support their families and communities. Women of color and immigrants are at a deep disadvantage, finding the least support of all along the path to successful business ownership. As Georgia’s population of women and people of color grows, the state needs to deploy new strategies to bolster economic inclusion for these groups. The future prosperity of all Georgians depends on fair and inclusive, gender- and race-conscious policies to close the wealth divide in the state.

More technical assistance, better access to capital resources, and new targeted, inclusive, and transparent state contracting goals offer a path to help the state’s women entrepreneurs build on the success of their businesses. This business growth can increase women’s wealth by providing them with greater personal income that can be used to increase their savings and other assets. That will lead to a more financially secure future for their children and contribute to the economic growth of their local communities.

Endnotes

[1] “2018 State of Women-Owned Businesses: Summary Tables”, American Express OPEN

[2] GBPI analysis of the 2016 Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, U.S. Census Bureau

[3] Melissa Johnson, “Laying the Foundation: A Wealth-Building Agenda for Georgia Women”, Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, 2017

[4] “Lifting as We Climb: Women of Color, Wealth, and America’s Future”, Insight Center for Community Economic Development, 2010

[5] Prosperity Now Scorecard, Prosperity Now, 2017

[6] Data and analysis of 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation provided by Prosperity Now

[7] Ibid.

[8] Alexandra Bastian, “Employment Equity: Putting Georgia on the Path to Inclusive Prosperity”, PolicyLink, 2017

[9] “The Growth and Development of Women-Owned Enterprises in the United States, 2002 – 2012,” National Women’s Business Council.

[10] “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America”, Association for Enterprise Opportunity, 2017

[11] GBPI analysis of the 2016 American Community Survey, US Census.

[12] “Innovation and Intellectual Property Among Women Entrepreneurs”, Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2018

[13] “Bigger Than You Think: The Economic Impact of Microbusiness in the United States”, Association for Enterprise Opportunity, 2013

[14] “Bigger Than You Think: The Economic Impact of Microbusiness in the United States”, Association for Enterprise Opportunity, 2013

[15] “2018 State of Women-Owned Businesses: Summary Tables”, American Express OPEN

[16] Melissa Johnson, “Laying the Foundation: A Wealth-Building Agenda for Georgia Women”, Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, 2017

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Capital Access for Women: Profile and Analysis of U.S. Best Practice Programs”, Kauffman Foundation, 2006

[19] Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Women-Owned Firms”, The Federal Reserve Banks of New York & Kansas City, 2016.

[20] “The State of Online Small Business Lending”, Fundera, Inc., 2018

[21] Valentina Zarya, “Female Founders got 2% of Venture Capital Dollars in 2017”, Fortune, 2018

[22] “The State of Online Small Business Lending”, Fundera, Inc., 2018

[23] “Black Women Business Startups”, The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 2016

[24] Ibid.

[25] FY2016 Supplier Orientation, Georgia Department of Administrative Services. http://doas.ga.gov/assets/State%20Purchasing/Documents%20for%20Getting%20Started%20as%20a%20Supplier/FY2016%20Supplier%20Orientation.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

[26] FAQ: Minority Business Enterprise Certification”, http://doas.ga.gov/state-purchasing/FAQ. Accessed September 11, 2017.

[27] “Georgia Department of Transportation Disparity Study”, 2016

[28] https://www.sba.gov/about-sba/sba-newsroom/press-releases-media-advisories/federal-government-achieves-small-business-procurement-contracting-goal-4th-consecutive-year

[29] FY2016-2018 Federal Transit Administration Disadvantaged Business Enterprise Program Goals, Georgia Department of Transportation http://www.dot.ga.gov/PartnerSmart/Business/Documents/DBE/DBEGoalFY2016-2018-b.pdf

[30] “Contracting for Equity: Best Local Government Practices that Advance Racial Equity in Government Contracting and Procurement”, Insight Center for Community Economic Development, 2015

[31] See “Minority Business Enterprise Program” Governor’s Office of Small, Minority & Women Business Affairs, http://goma.maryland.gov/Pages/mbe-Program.aspx . Accessed September 11, 2017.

[32] “2016 Fulton County Small Business Study”, Keen Independent Research

[33] Dekalb County Ordinance, Sec. 2-204; Valdosta, GA ordinance section 4.5.1;

[34] A larger list of state-sponsored programs can be found in “Laying the Foundation: A Wealth-Building Agenda for Georgia Women”, Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, 2017

[35] “Kauffman Compilation: Research on Immigration and Entrepreneurship”, Kauffman Foundation, 2016

[36] “2017 State of Women-Owned Businesses: Summary Tables”, American Express OPEN

[37] https://thelaa.org/focus-areas/economic-empowerment/

[38] An immigrant is someone who chooses to resettle to another country; A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her home country

[39] http://refugeewomensnetworkinc.org/projects/