*The following information reflects the legislation passed by the United States House of Representatives on May 22, 2025. Additional information will be provided as the bill progresses.

![]()

Introduction and Summary

Congress is currently negotiating a federal budget package. To pay for tax cuts for wealthy individuals and corporations, Congress is looking for ways to decrease federal spending on programs like Medicaid. The budget resolution already passed by Congress instructed the House Energy & Commerce committee to find $880 billion in cuts for programs under its jurisdiction, the largest of which is Medicaid. On May 22, the House of Representative passed a bill that specifically outlines how Medicaid cuts would be implemented. This policy brief is intended for state-level policymakers and advocates to help them better understand the proposed Medicaid changes that would have the greatest fiscal impact for Georgia.

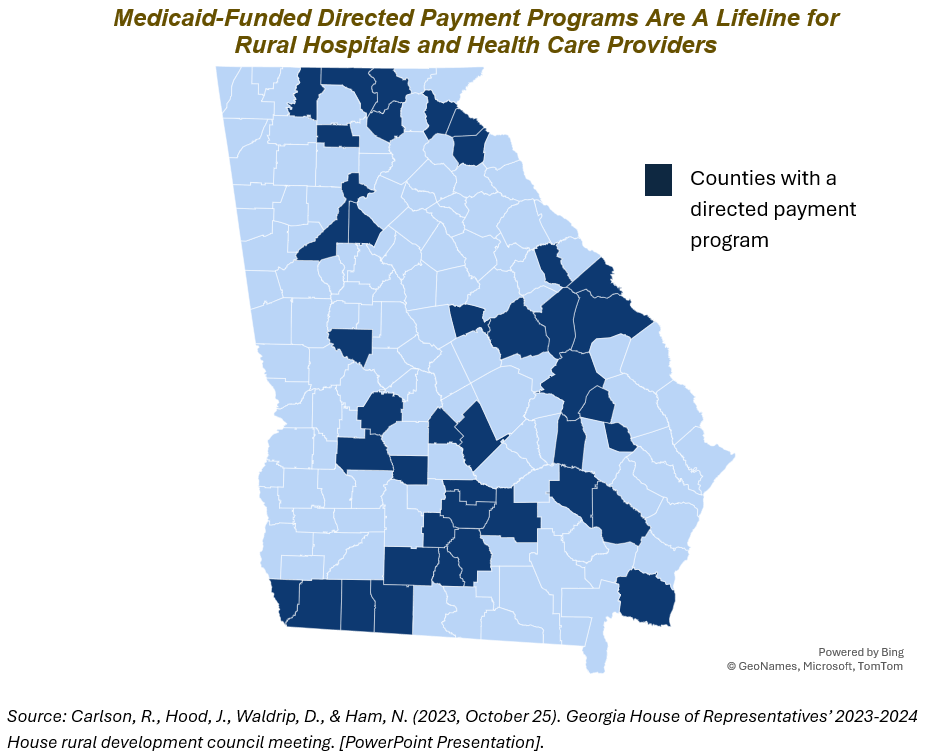

Georgia has one of the highest uninsured rates in the country and ranks 48th in the nation based on key health care measures, such as access, quality and preventive services.[1],[2] Sixty-five rural counties either have no hospital or have a hospital under significant financial strain, like Southeast Georgia Health System in Camden County and Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Habersham County.[3],[4] In other words, Georgia’s healthcare system is under stress, and the relative impact is greatest in rural Georgia.

Although this new legislation has greater implications for other states with more comprehensive Medicaid programs, even moderate changes for Georgia would put pressure on a system that is already overburdened. Among other important impacts, the bill language that passed out of the House of Representatives on May 22, 2025:

- Limits Georgia’s options for financing its state share of Medicaid and for using directed payments to respond to future healthcare system needs, particularly those in rural Georgia

- Eliminates a federal financial incentive to fully close the state’s health insurance coverage gap

- Adds complexity to Georgia’s already costly and ineffective work reporting requirement for low-income adults and potentially adds a new paperwork burden for exempt Georgians

This proposed legislation would shift Medicaid costs from the federal government to the state and force the state to either pick up the tab or make difficult decisions in the future about who gets covered and what kind of benefits they receive. It would also make it harder for the state to support hospitals as more uninsured or underinsured patients come through their doors and the hospitals’ uncompensated care costs rise. An estimated 160,000 Georgians would become uninsured due to combined effect of the Medicaid changes highlighted above along with other health care-related bill provisions.[5] Premiums will increase substantially for Georgians who get their health insurance through Georgia’s state-based marketplace, Georgia Access, if Congress allows the enhanced premium tax credits to expire at the end of 2025. Taken together, the expiration of those tax credits and the Medicaid changes in the House’s bill would result in an estimated 610,000 Georgians becoming uninsured.[6] The bottom-line is this: this legislation has the potential to take life-saving health coverage from eligible Georgians at a time when families are already struggling to make ends meet while also eroding the state’s rural healthcare system and threatening local economies.

How Medicaid Is Currently Financed in Georgia

Medicaid is a federal-state partnership that provides access to health coverage for about 2 million Georgians, including about 2 in every 5 children.[7] The program is jointly financed by the state and federal government. Currently, the federal government pays about 66% of costs for health care benefits, and the state pays the remainder.

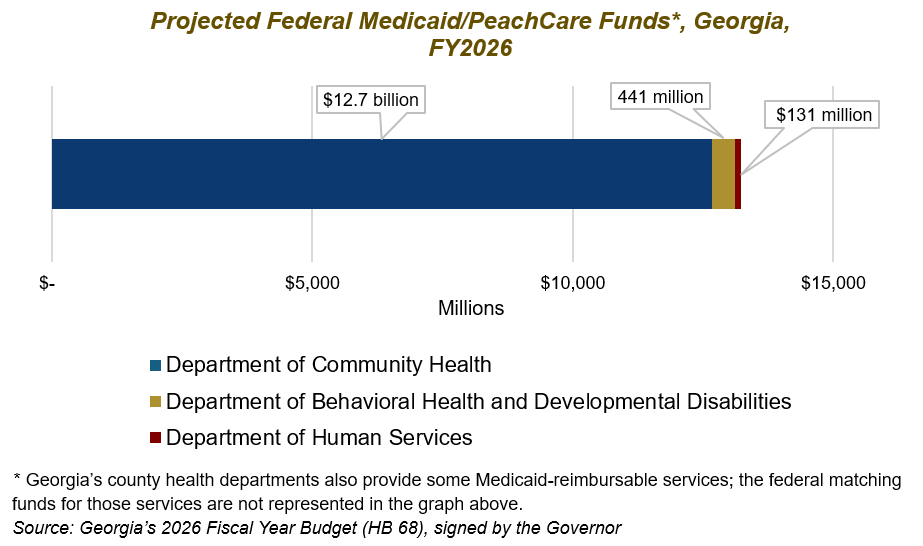

Federal Medicaid is Georgia’s largest single source of federal revenue. In fact, federal Medicaid dollars alone account for about 1 in every 5 dollars spent by the state.[8] In state fiscal year 2026 (FY 2026), Georgia expects to receive about $13 billion in federal Medicaid and PeachCare funds spread out across three primary agencies: about 96% (or $12,661,331,013) of Georgia’s federal Medicaid funds are allocated to the Department of Community Health; about 3% (or $440,688,213) to the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities; and about 1% (or $130,569,082) to the Department of Human Services.

Potential Federal Medicaid Changes with Major Fiscal Implications

Provider Taxes

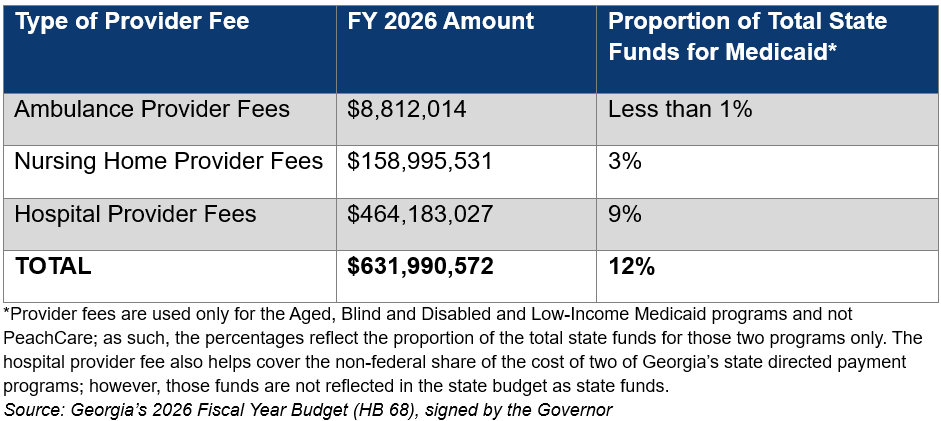

Provider taxes (also known as provider fees) help states, like Georgia, to pay the state share of Medicaid costs. Data show that states rely more heavily on provider taxes during and after economic recessions – when state revenue goes down and the number of people relying on Medicaid for health coverage increases.[9] Although state general funds make up the majority of state Medicaid spending, provider fees provide critical support and account for about 12% of Georgia’s total state funds for Medicaid.

What does the House budget propose? Freeze state provider taxes at current rates and prohibit states from establishing new provider taxes.[a]

Bottom-line for Georgia: Georgia’s provider taxes are already at the lowest rate compared to 48 other states.[10] Freezing state provider taxes deprives Georgia of an important tool for filling holes in the state’s health care budget during economic downturns. Preserving the state’s ability to raise provider taxes would help ensure that Georgians stay covered and that health care facilities, like nursing homes and safety net hospitals, remain open.[11] Freezing provider taxes could also impact Georgia’s ability to cover the rising cost of optional Medicaid benefits, like prescription drugs, home-and community-based services and dental care.

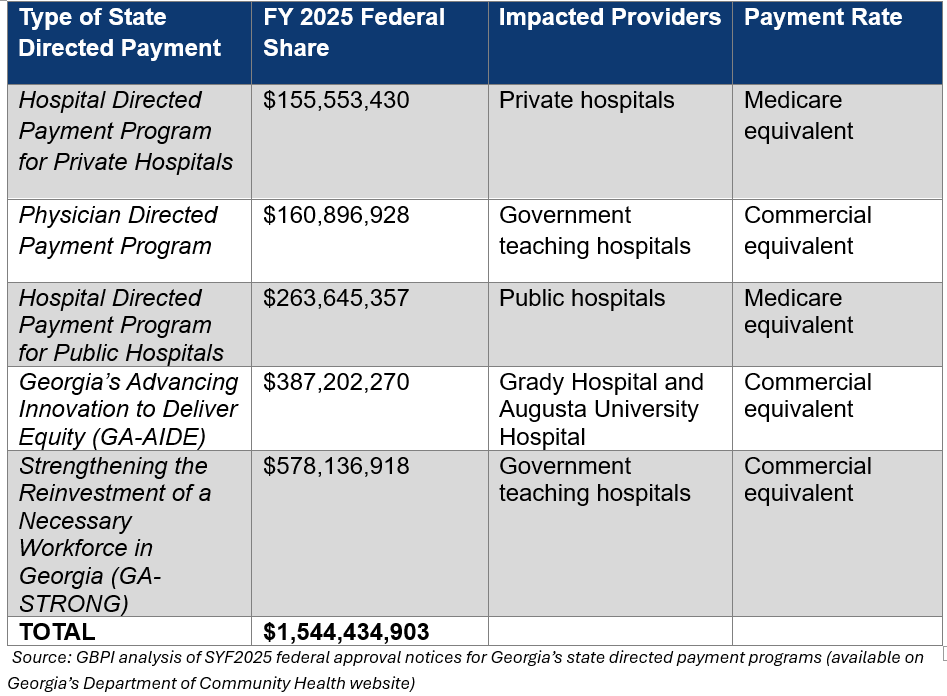

State Directed Payment Program

State directed payment programs (DPPs) allow states to direct Medicaid managed care organizations to pay providers according to specific rates or methods. In general, Medicaid reimburses health care providers at a lower rate than Medicare or commercial plans. DPPs allow states to more adequately compensate providers and provide a critical financial boost to safety net hospitals, such as those in rural areas.[12] In fact, Georgia’s Department of Community Health projected that DPPs would eliminate uncompensated care costs for small rural hospitals and cut total uncompensated costs across the state by 50%.[13] In fiscal year 2025, the state is receiving an estimated $1.5 billion in federal dollars to support DPP. Unlike other Medicaid-funded programs, the non-federal share of DPP does not need to be financed by state general funds. To cover the non-federal share of the cost, Georgia relies on hospital provider taxes and on intergovernmental transfers that allow hospital authorities or related government-entities, like the Fulton/DeKalb Hospital Authority that oversees Grady Hospital, to transfer funding to the state.[14]

What does the House budget propose? Limit DPPs from exceeding the Medicare payment rate (100% of the Medicare rate in states that have expanded Medicaid and 110% in non-expansion states like Georgia)

Bottom-line for Georgia: The immediate impact for Georgia would be limited since existing DPPs are grandfathered in; however, it is unclear if three of Georgia’s DPPs (see table above) would need to reduce their payment rates from the commercial equivalent to Medicare rates after the current yearly approval period ends. In addition, the bill language disincentivizes full Medicaid expansion: if Georgia were to cover adults with household incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level in the future, allowable DPP payment rates would need to drop from 110% to 100% of the Medicare rate. Ultimately, this proposal removes the state’s ability to be nimble and respond to shifting state needs in future DPP applications and puts the state’s ability to shore up the financial viability of Georgia’s rural hospital system at risk.

Federal Incentive for New Medicaid Expansion States

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) offers an added financial incentive, on top of the existing 90% federal match for newly eligible enrollees, for the final 10 states that have yet to fully expand Medicaid for uninsured adults with low incomes. Georgia’s state auditor estimates that the ARPA incentive would bring about $1 billion in additional federal revenue to Georgia over the course of two years.[15] If Georgia were to fully expand Medicaid to low-income adults earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level (about $44,000 for a family of four), the federal funds flowing to our state would help offset the state costs of full Medicaid expansion for at least the first two years. Modeling also indicates that these federal funds would stimulate Georgia’s economy – helping create over 50,000 new jobs and increase state economic output by $9.4 billion.[16]

What does the House budget propose? Sunset the two-year 5% enhanced federal match on existing Medicaid enrollees for states that fully expand their Medicaid programs

Bottom-line for Georgia: If Georgia fully expands Medicaid to low-income uninsured adults in the future, either by offering low-income adults coverage through Medicaid or by purchasing them qualified health plans through the state-based marketplace, the state would no longer be able to take advantage of this Medicaid expansion ‘signing bonus’ and some of the downstream economic benefits.

Work Requirements

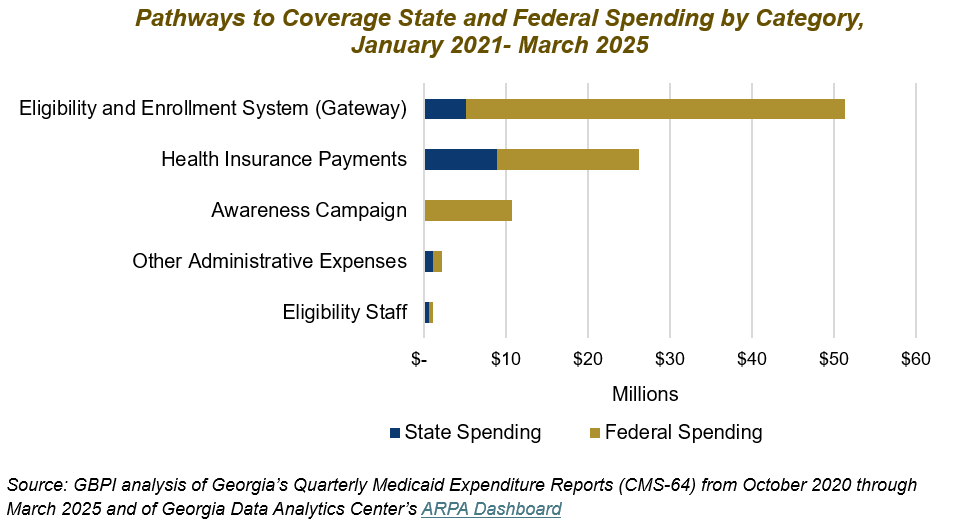

In July 2023, Georgia launched the Pathways to Coverage program, which offers Medicaid coverage to low-income, uninsured adults who report 80 hours per month of work, higher education, volunteering or some other combination of qualifying activities. Currently, Georgia is the only state that offers Medicaid coverage to low-income adults contingent upon this type of work or other qualifying activities requirement. Georgia’s experience with Pathways to Coverage clearly demonstrates the pitfalls of implementing policies that take away or make access to basic needs contingent upon cumbersome reporting processes[17], including:

- Extra bureaucratic red tape for Medicaid applicants/enrollees and state agency staff

- High administrative costs, which are mostly covered by the federal government

- Low enrollment

Most existing Medicaid enrollees as well as those in the health insurance coverage gap are already working themselves or are in a household with at least one worker.[18], However, they are often employed in jobs that do not offer employer-sponsored coverage, such as construction, food service and retail.[19] Those who are not working are often caring for children or other family members, living with a serious health condition or disability or are enrolled in school.[20] Prior research shows that work reporting requirements have limited impact on long-term employment gains.[21],[22] Conversely, being in poor health increases the risk of job loss, while having access to health insurance can help people stay employed and increase income.[23],[24]

What does the House propose? Make Medicaid eligibility for low-income, able-bodied adults without dependents contingent upon reporting 80 hours per month of work or some other qualifying ‘community engagement’ activity (with exemptions for pregnant women, former foster youth under the age of 26, individuals with a chronic substance use disorder, caregivers of individuals with disabilities, etc.)

Bottom-line for Georgia: Some of the exemptions in the House proposal do not align with Georgia’s current work reporting requirement and may require Georgia to amend who receives an exemption under the Pathways to Coverage program. Depending upon how this policy is implemented at the state level, it may also result in Georgians covered by traditional Medicaid having to submit verification of their exemption from the work requirement. Based on Arkansas’ experience with work reporting exemptions, this additional red tape could result in procedural denials – meaning eligible Georgians, like individuals with a disability and pregnant/postpartum women, lose their health coverage for ‘paperwork’ reasons.[25] It would likely result in Georgia spending even more on costly technology upgrades to the state’s outdated eligibility and enrollment system and increase the untenable workload for Georgia’s frontline eligibility caseworkers.[26],[27],[28]

Conclusion

The potential Medicaid changes outlined in this policy brief are those with the greatest financial implications. However, the full proposed legislation includes many other cuts and policy changes that threaten the health and economic security of Georgia’s low-income families and push Georgia’s rural healthcare system to the brink. Federal lawmakers should protect Medicaid and reject these changes that stand in the way of well-being and economic progress here in Georgia.

Endnotes

[a] An additional provision in the House budget proposal penalizes states based on how they are applying the formula used to determine if a provider tax is ‘redistributive’; it is unclear if Georgia would be impacted.

[1] 2023 ACS tables: State and county uninsured rates, with comparison year 2022. (2024, September 17). State Health Access Data Assistance Center. https://www.shadac.org/news/2023-acs-tables-state-and-county-uninsured-rates-comparison-year-2022

[2] Georgia state summary. (2025) America’s Health Rankings. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2024-annual-report

[3] Chan, L. (2024, March 4). The state of Georgia’s healthcare system. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/statehealthcaresources/

[4] Rural hospital tax credit – 2025 ranking of financial need. (2025). Georgia Department of Community Health. https://dch.georgia.gov/document/document/rural-hospital-tax-credit-2025-ranking-financial-need-revised-1252024-rvd-51525/download

[5] Burns, A., Ortaliza, J., Lo, J., Rae, M. & Cox, C. (2025, May 20). How will the 2025 reconciliation bill affect the uninsured rate in each state? Allocating CBO’s partial estimates of coverage loss. KKF. https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/issue-brief/how-will-the-2025-reconciliation-bill-affect-the-uninsured-rate-in-each-state-allocating-cbos-partial-estimates-of-coverage-loss/

[6] Ibid.

[7] The Commonwealth Fund. (2025, January 30). What Medicaid brings to Georgia. https://interactives.commonwealthfund.org/2025/medicaid-fact-sheets/Georgia.pdf

[8] Chan, L. (2025, February 7). Overview: 2026 fiscal year budget for the Georgia Department of Community Health. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/overview-2026-fiscal-year-budget-for-the-georgia-department-of-community-health/

[9] Mitchell, A. (2024, December 30). Medicaid provider taxes. Congressional Research Services. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RS22843

[10] Burns, A., Hinton, E., Williams, E., & Rudowitz, R. (2025, March 26). 5 key facts about Medicaid and provider taxes. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/5-key-facts-about-medicaid-and-provider-taxes/

[11] Park, Edwin. (2025, May 13). House Energy and Commerce Committee reconciliation bill would restrict state use of provider taxes and undermine state financing of Medicaid. Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2025/05/13/house-energy-and-commerce-committee-reconciliation-bill-would-restrict-state-use-of-provider-taxes-and-undermine-state-financing-of-medicaid/

[12] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. (2024). Directed payments in Medicaid managed care. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/directed-payments-in-medicaid-managed-care/

[13] Noggle, C. (2023). Georgia Department of Community Health. Amended FY 2023 and FY 2024 Governor’s budget recommendation. [PowerPoint Presentation]. Joint Appropriations Committee. https://www.legis.ga.gov/api/document/docs/default-source/house-budget-and-research-office-document-library/2023-joint-budget-hearings/department_of_community_health.pdf?sfvrsn=71411797_2

[14] Carlson, R., Hood, J., Waldrip, D., & Ham, N. (2023, October 25). Georgia House of Representatives’ 2023-2024 House rural development council meeting. [PowerPoint Presentation]. https://www.house.ga.gov/Documents/CommitteeDocuments/2023/Rural_Development_Council/Oct%2025/4%20DCH%20House%20Rural%20Committee%20meeting_Final.pdf

[15] Griffin, G. (2025, March 3). Fiscal note on House Bill 97 (LC 52 0636). Georgia Department of Audits & Accounts. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2025/lc-52-0636/download

[16] Evangelakis, P. (2024, March 28). Economic impacts of Medicaid expansion in Georgia. REMI. https://www.remi.com/topics-and-studies/economic-impacts-of-medicaid-expansion-in-georgia/

[17] Chan, L. (2024, October 29). Georgia’s Pathways to Coverage program: The first year in review. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgias-pathways-to-coverage-program-the-first-year-in-review/

[18] Hinton, E & Rudowitz, R. (2025, February 18). 5 key facts about Medicaid work requirements. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/5-key-facts-about-medicaid-work-requirements/

[19] Cervantes, S, Bell, C., Tolbert, J., & Damico, A. (2025, February 25). How many uninsured are in the coverage gap and how many could be eligible if all states adopted the Medicaid expansion? KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-many-uninsured-are-in-the-coverage-gap-and-how-many-could-be-eligible-if-all-states-adopted-the-medicaid-expansion/

[20] Rosenbaum, S., Cohen, M., Tavares, J.L., & Barkoff, A. (2025, April 30). Who’s affected by Medicaid work requirements? It’s not who you think. Milbank Quarterly Opinion. https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/opinions/whos-affected-by-medicaid-work-requirements-its-not-who-you-think/

[21] Pavetti, L., Bolen, E., Harker, L., Orris, A., & Mazzara, A. (2023). Expanding work requirements would make it harder for people to meet basic needs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/expanding-work-requirements-would-make-it-harder-for-people-to-meet

[22] Gangopadhyaya, A. & Karpman, M. (2025, April 9). The impact of Arkansas Medicaid work requirements on coverage and employment: Estimating effects using National Survey Data. Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.14624

[23] Hinton, E & Rudowitz, R. (2025, February 18). 5 key facts about Medicaid work requirements. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/5-key-facts-about-medicaid-work-requirements/

[24] Chen, B. & Staiger, B. (2025, April 28). Medicaid expansion increased income among newly-eligible adults. Health Affairs Scholar. https://doi.org/10.1093/haschl/qxaf091

[25] Harker, L. (2023). Pain but no gain: Arkansas’ failed Medicaid work-reporting requirements should not be a model. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/pain-but-no-gain-arkansas-failed-medicaid-work-reporting-requirements-should-not-be

[26] Chan, L. (2024, October 29). Georgia’s Pathways to Coverage program: The first year in review. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgias-pathways-to-coverage-program-the-first-year-in-review/

[27] Lucas, L. (2025, April 1). Legislation could require plan to address backlog of federal benefit cases in Georgia. 11 Alive News. https://www.11alive.com/article/news/state/georgia-lawmakers-legislation-provision-to-address-medicaid-snap-tanf-benefits-backlog/85-df10c637-cc89-4ed4-adda-f4165e404ec7

[28] Coker, M. (2025, February 19). Georgia touts its Medicaid experiment as a success- the number tell a different story. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/georgia-medicaid-work-requirement-pathways-to-coverage-hurdles