The House is rushing the process to fundamentally change the structure of the SNAP program. They held no hearings before the House Agriculture Committee decided to make these dramatic changes. Therefore, some critical details are unknown because they are not addressed in the current legislation, nor have they been discussed by the committee. This analysis uses the best available data and information for this brief as of May 21, 2025. Additional information will be provided as the bill progresses.

![]()

The U.S. House of Representatives is currently considering plans to drastically cut basic needs programs, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid, to help pay for an extension and expansion of tax cuts for wealthy corporations and individuals. The House Committee on Agriculture recently marked up legislation that would completely change the structure of SNAP, also known as food stamps, by shifting a share of the benefit costs onto states. It would also expand ineffective work reporting requirements, restrict future benefit increases, end access for certain qualified immigrants and make other changes. (This policy brief is intended for state-level policymakers and advocates to help them better understand the state fiscal and economic impact of these potential cuts.)

The provisions in this bill would make it harder for people with low incomes to afford the growing cost of groceries. Currently, food prices are more than the value of maximum SNAP benefits in every Georgia county and 10% or more than SNAP benefits in 142 counties.[1] While the bill does not outright cut SNAP benefits, certain provisions would still lead to cuts to many households, who could lose some or all of their benefits. Additionally, limiting the increase of SNAP benefits in the future would mean that SNAP would fall further behind the cost of food over time.

Some members of Congress have made arguments that Georgia’s multibillion-dollar surplus will allow the state to absorb these new costs. This is not a viable option: Even if Georgia’s surplus is tapped, it is not a sustainable way to backfill the magnitude of federal funding cuts that would be shifted to Georgia’s state budget over the long term.

SNAP promotes food security and stronger local economies

SNAP provides food assistance to individuals and families with low incomes and reduces the likelihood of being food insecure by 30%.[2] These benefits are 100% federally funded and help recipients afford the growing cost of food, support their economic stability and maintain their health. In Georgia, about 1.4 million people, or about 700,000 households, utilized SNAP in 2024.[3] While SNAP does a lot of good to support individuals and families, it is not an extravagant benefit. The average SNAP benefit is $6.20 per person per day.[4]

SNAP supports local economies as well. In 2023, Georgia issued more than $3 billion in federal SNAP benefits. Individuals then spent those benefits in about 10,000 retailers throughout the state.[5] The National Grocers Association estimates that at grocery stores alone, SNAP benefits helped generate more than $343 million in grocery industry wages in Georgia.[6] During an economic downturn, every $1 of SNAP benefits generates between $1.50 and $1.80 in economic activity.[7] Rural areas disproportionately benefit from SNAP as they are more likely to utilize SNAP compared to metropolitan areas.[8]

The House bill’s fundamental change to the structure of SNAP creates a dilemma for Georgia, likely leading to reductions in SNAP benefits and/or caseload and layoffs

The bill expands the state’s SNAP expenses in two ways: requiring states to cover a share of SNAP benefits and increasing the states’ share of administrative costs from 50% to 75%. Starting in 2028, every state will have to cover a share of benefits; what share the state must pay will depend on the state’s ability to reduce any administrative mistakes that could lead to improper payments to beneficiaries. Paradoxically, the legislation would also reduce the state’s ability to establish and maintain efficient benefit issuance processes because Georgia would likely reduce staff under a 75% administrative cost share. The change to the structure of SNAP will most likely push state leaders to cut the program. The ultimate impact is significant harm to people who are at risk of food insecurity.

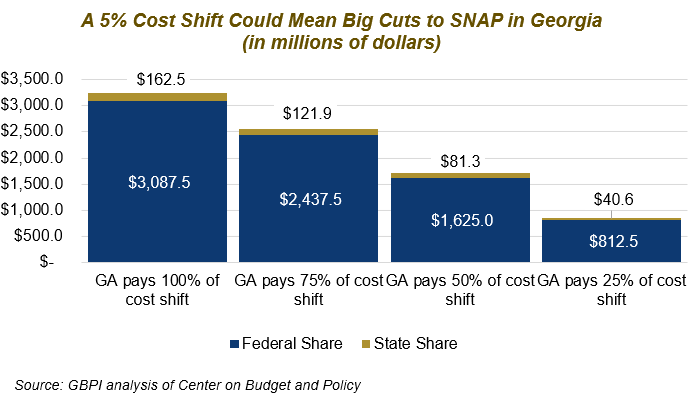

A SNAP benefit cost shift would be expensive for Georgia and harmful for SNAP recipients

Today, SNAP benefits are 100% federally funded, but the draft legislation proposes that all states be required to pay at least 5% of SNAP benefits starting in January 2028. Five percent of SNAP benefits today would be more than $162 million.[9] If Georgia leaders decided they could not afford $162 million, they would likely cut the SNAP program to establish a lower dollar amount. That would shrink the federal and state funds for SNAP.

The bill goes further and establishes a sliding scale based on error rates. Error rates include agency overpayments and underpayments to SNAP recipients. Both types of improper payments are largely the result of human error by state workers and/or clients, not fraud.[10] The bill says that if a state has a payment error rate of between 6 and 8% the state cost requirement increases to 15%; an error rate between 8 and 10% increases the cost shift to 20%. If the error rate is 10% or higher, the state share is 25%. In 2023, Georgia was one of several states that had an error rate of more than 10%. If this policy went into effect this year, the state share would be about $812 million based on current spending.[11]

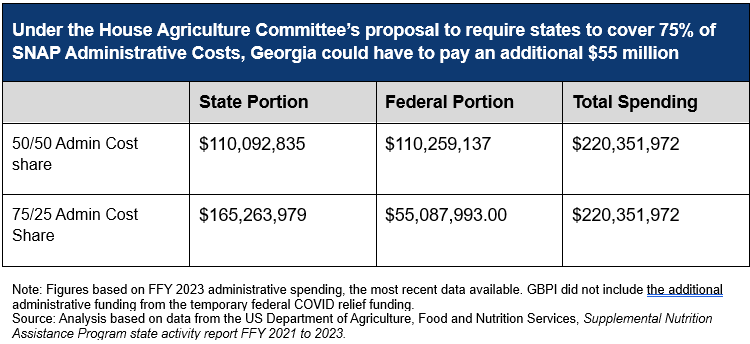

Shifting more of the administrative costs onto states would likely mean layoffs and an increased risk of agency inefficiency

During the markup of the bill, Congressional members stated that the threat of an increased benefit cost share would motivate the state to improve its administrative processes.[12] However, a separate proposal to increase the state share of administrative costs would undermine that goal.

Requiring Georgia to take on 75% of the administrative costs could be a major increase for the state. For example, in federal fiscal (FFY) year 2023, the state spent about $110 million on administrative costs, and the federal government spent about $110 million, for a total of $220 million.[13] Under this new policy, if the state wanted to maintain the total administrative spending from FFY 2023, it would have to pay an additional $55 million annually.

If state leaders decide not to cover SNAP administrative costs at that level, they may lower the administrative expenses and trigger the federal government to lower what it contributes as well. Fewer administrative resources for the Georgia Department of Human Services’ administration would likely mean cuts in the form of layoffs.[14] However, a cut to staff as a cost-saving measure may make it harder to keep error rates low as high workloads could lead to more mistakes. Instead of the state improving payment performance, it would likely struggle to keep error rates low, putting it at risk of an even greater benefit-cost share.

Ineffective work reporting requirements would cut food assistance for hundreds of thousands of Georgians

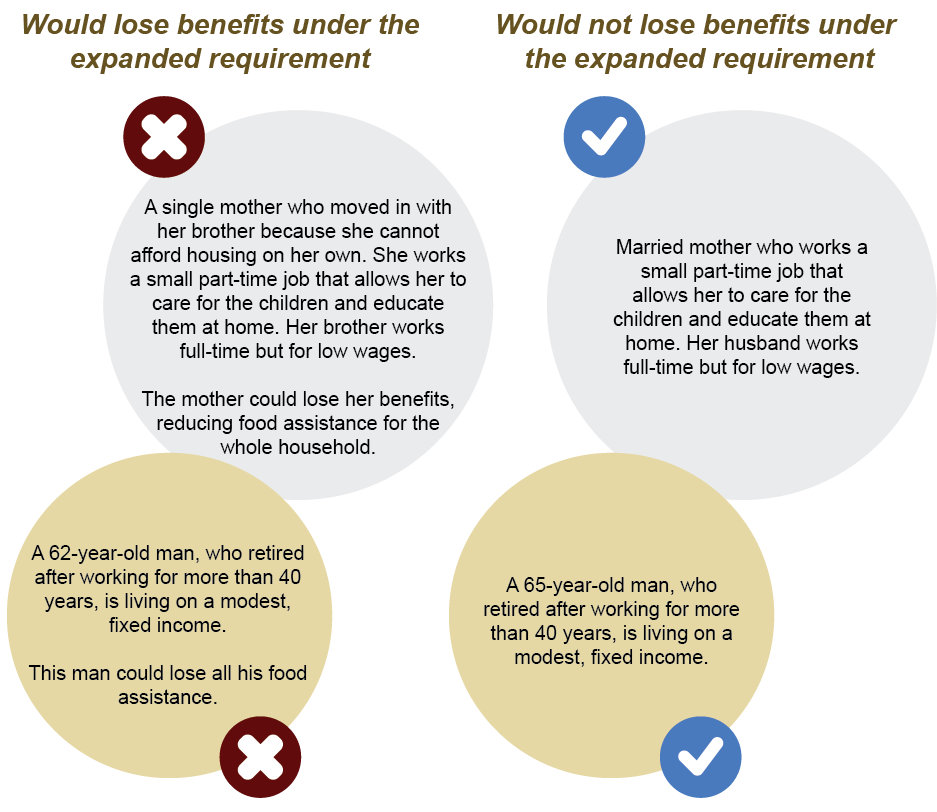

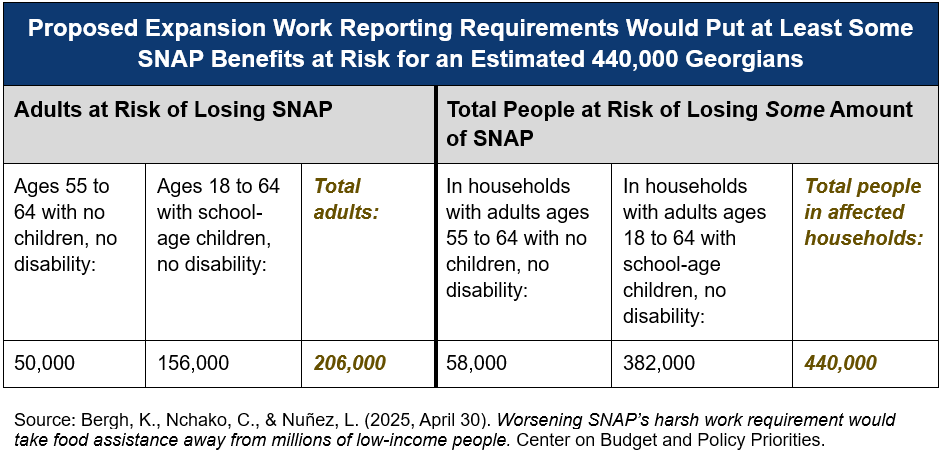

The House Agriculture Committee proposes to expand policies that take away benefits from those who cannot show they are meeting or are exempt from a work requirement. Their bill would include older adults and parents with school-aged children.

SNAP’s current policy states that adults aged 18 to 54[15] without a documented disability and not living with children have three months to receive benefits if they do not demonstrate to the state that they are working 20 hours a week. If they cannot meet this requirement after three months, they are ineligible for three years.

Many people who turn to SNAP are between jobs, do not get enough consistent hours at work, live in a rural area with limited access to jobs or are caring for a family member, which prevents them from working. Research studies find little evidence of work reporting requirements leading to economically secure jobs; instead, these requirements kick people off basic needs programs.[16]

The proposal would ignore the complex realities of people with low incomes and would expand the reporting requirement to:

- Parents or grandparents living with children 7 or older. There is an exception for married couples; a person who is caring for children, but not otherwise working, does not have to meet these requirements as long as they are married and reside with an individual who does comply with the work rules.

- Older adults not living with children and without a verified disability up to age 65.[17]

People living in households that were previously exempt could lose some or all their benefits, while others who are similarly situated may not.

The proposal puts at risk some or all the food security for up to 440,000 people. For example, if a parent cannot meet the work reporting requirement, the family will have less food assistance to buy food, but the same number of people to feed.

Other provisions in the bill would exacerbate harm

The bill includes other harsh measures that make SNAP less effective at supporting food security and nutrition.

- Freeze future increases to the cost of the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP)—a USDA diet plan designed to be nutritionally adequate at a very low cost. The FFY 2021 update to the TFP was the first update to the plan in 50 years, and it increased the per-person-per-day value of SNAP benefits from $4.80 to $6.20.[18] The House change would return to the previous standard of only adjusting SNAP benefits relative to inflation. With food prices rising faster than overall prices, the purchasing power of SNAP benefits will erode.

- Prevent all legally present “qualified” immigrants who are not Lawful Permanent Residents from receiving SNAP. This includes low-income legally present immigrants such as immigrants granted asylum, refugee status, humanitarian parolees and conditional entrants.

- Eliminates the SNAP Nutrition Education program, which provides nutrition and obesity prevention education. SNAP Ed provides funding to Georgia’s Department of Public Health, universities and non-profits to provide nutrition education to people eligible for SNAP benefits. In 2024, SNAP Ed reached 40,000 people, and in FFY 2025, Georgia’s grantees received a total of $10.5 million.[19]

Conclusion

Hunger is a policy choice. If Congress approves this bill in its current form, it will walk away from the federal government’s 60-year commitment to support the food insecurity of millions of Americans. The cost shift to states is so great that some states may choose to opt out of the SNAP program. Individuals and families would struggle to meet their basic needs. Children living in families with low income would likely have worse health and life outcomes. Seniors would be forced to choose between medicine and food. Local economies, especially in rural areas, would suffer.

Congress can make a different choice to support the well-being of all Americans by supporting basic assistance programs and asking the richest individuals and companies to pay their fair share.

Endnotes

[1] Waxman, E., Gupta, P., & Gundersen, C. (2024). The gap between SNAP benefits and meal costs. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/data-tools/does-snap-cover-cost-meal-your-county

[2] Ratcliffe, C., & McKernan, S. M. (2010, April). How much does SNAP reduce food insecurity? US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84335#:~:text=The%20results%20suggest%20that%20receiving,of%20reducing%20food%2Drelated%20hardship

[3] Data from the Department of Human Services, Division of Family and Children Services.

[4] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2024, November 25). Policy basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap

[5] U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service. (2024). SNAP retailer locator. https://usda-fns.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=15e1c457b56c4a729861d015cd626a23

[6] National Grocers Association. (2025). Georgia SNAP economic impact. https://grocers.guerrillaeconomics.net/reports/3d35f2a0-06f3-4c7d-a4a5-fce5357dbdfc?

[7] Canning, P., & Mentzer Morrison, R. (2019, July 18). Quantifying the impact of SNAP benefits on the U.S. economy and jobs. USDA, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2019/july/quantifying-the-impact-of-snap-benefits-on-the-us-economy-and-jobs/

[8] Finch Floyd, I. (2023, September 6). The Basics of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in Georgia. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/the-basics-of-the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-in-georgia/?_gl=1*1k2oyuf*_up*MQ..*_ga*NzkzMTY2MzgwLjE3NDc0MTAyMjg.*_ga_ZWZC5HZ1YJ*czE3NDc0MTAyMjckbzEkZzEkdDE3NDc0MTAyNDEkajAkbDAkaDA

[9] Rosenbaum, D., Bergh, K., & Tharpe, W. (2025, March 11). Imposing SNAP food benefit costs on states would worsen hunger, hurt states’ ability to meet residents’ needs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/imposing-snap-food-benefit-costs-on-states-would-worsen-hunger-hurt-states#mandating-that-states-cover-even-cbpp-anchor

[10] Rosenbaum, D., & Bergh, K. (2024, June 21). SNAP includes extensive payment accuracy system. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-includes-extensive-payment-accuracy-system

[11] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Services. (2024, June 28). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Payment error rates, fiscal year 2023. https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-fy23-qc-payment-error-rate.pdf;

Rosenbaum, D., Bergh, K., & Tharpe, W. (2025, March 11). Imposing SNAP food benefit costs on states would worsen hunger, hurt states’ ability to meet residents’ needs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/imposing-snap-food-benefit-costs-on-states-would-worsen-hunger-hurt-states#mandating-that-states-cover-even-cbpp-anchor

[12] House Committee on Agriculture. (2025, May 13). SNAP integrity and farm security full committee markup. https://www.youtube.com/live/qmeLZYEAxwI?si=jC–C-TqaA7w7VQc.

[13] FFY 2023 administrative spending also included additional American Rescue Plan resource to provide added support to state agencies.

[14] The Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) has been hiring staff since 2024 to help address years of high turnover and high workloads. For the FY 2026 budget, the legislature included a much-needed $3,000 pay increase for DFCS eligibility staff for FY 2026.

[15] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (updated, 2024, September 30). A quick guide to SNAP eligibility and benefits. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/11-18-08fa.pdf

[16] Pavetti, L. (2018, April 3). Evidence doesn’t support claims of success of TANF work requirements. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/evidence-doesnt-support-claims-of-success-of-tanf-work-requirements.

Gray, C., Leive, A., Prager, E., Pukelis, K., & Zaki, M. (2023). Employed in a SNAP: The impact of work requirements on program participation and labor supply. American Economic Association Journal, 15(1), 306-341. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20200561

Feng, W. (2021). The effects of changing SNAP work requirement on the health and employment outcomes of able-bodied adults without dependents. Journal of the American Nutrition Association, 41(3), 281-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2021.1879692;

Han, J. (2022). The impact of SNAP work requirements on labor supply. Labour Economics, 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2021.102089; Ku, L., Brantley, E., & Pillai, D. (2019). The effects of SNAP work requirements in reducing participation and benefits from 2013 to 2017. American Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1446-1451. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305232#:~:text=Expansions%20of%20work%20requirements%20caused%20about%20600%E2%80%89000%20participants,after%20work%20requirements%20were%20imposed.%20Public%20Health%20Implications;

Stacy, B., Scherpf, E., & Jo, Y. (2018, December 14). The impact of SNAP work requirements. working paper, https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2019/preliminary/paper/Z8ZhzBZt

[17] In 2023, Congress expanded the time limit to include adults ages 50-54 in the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA), and added new exemptions for adults who are experiencing homelessness, veterans, or under 24 and were in foster care when they turned 18. The House bill would allow the 2023 exemptions to sunset on October 1, 2030, as the original IRA law intended; the bill ends the IRA sunset on the work requirement for older adults.

[18] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2024, November 25). Policy basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap

[19] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. (2024, August 24). Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Nutrition Education (SNAP-Ed): Final allocations. https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/SNAPFY2025FinalSNAP-EdAllocationsMemoAugust2024_0.pdf