Overview

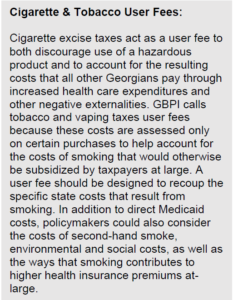

Georgia has the nation’s second lowest state cigarette user fee and lags most other states in adding common sense safeguards on the sale and use of tobacco products. With Georgia falling far short of recouping the costs of smoking through Medicaid alone, residents are effectively subsidizing the leading cause of preventable disease, death and disability. Overall, Georgia is estimated to spend approximately $782 million to cover the costs of smoking through state Medicaid spending in FY 2026, while the state is expected to raise about $486 million from all taxes and fees on tobacco products. This leaves a gap of at least $296 million in direct costs subsidized by taxpayers. This year, with the creation of the House Study Committee on the Costs & Effects of Smoking, Georgia lawmakers are looking to buck that trend.[1]

Georgia has the nation’s second lowest state cigarette user fee and lags most other states in adding common sense safeguards on the sale and use of tobacco products. With Georgia falling far short of recouping the costs of smoking through Medicaid alone, residents are effectively subsidizing the leading cause of preventable disease, death and disability. Overall, Georgia is estimated to spend approximately $782 million to cover the costs of smoking through state Medicaid spending in FY 2026, while the state is expected to raise about $486 million from all taxes and fees on tobacco products. This leaves a gap of at least $296 million in direct costs subsidized by taxpayers. This year, with the creation of the House Study Committee on the Costs & Effects of Smoking, Georgia lawmakers are looking to buck that trend.[1]

Georgia’s Costs and Revenues from Smoking are Out of Balance

Last year (2024), about 11.2% of all Georgia adults were smokers, slightly higher than the national average of 10.9%.[2] About 1.3% of Georgia adolescents reported smoking cigarettes, which is on par with the nation at-large.[3] On average, Georgia smokers consume an estimated 16 cigarettes per day, just short of a pack, which usually includes 20 cigarettes.[4]

Scholarship demonstrates that Georgians continue to suffer substantial economic losses due to rising health expenditures to treat illness caused by smoking and second-hand smoke, in addition to productivity losses from disease and premature death. Leading scholars quantify Georgia’s economic losses at $1,059 in per person income, with a cumulative loss of $11.3 billion in income that could have otherwise been earned statewide in 2020.[5] Other studies on the federal workforce show that reductions in smoking rates are associated with fewer heart disease and stroke hospitalizations, lower worker absenteeism and higher productivity levels.[6] Simply put, reducing smoking rates and encouraging Georgians to avoid tobacco use is likely to reduce long-term health care costs and strengthen the state’s economy.

In Georgia, the cost of smoking equates to a total of $2.5 billion per year in Medicaid costs, including about $782 million per year in direct costs paid by the state in Fiscal Year (FY) 2026.[7] With a higher incidence of smoking among Medicaid enrollees, about 15% of all Medicaid spending is attributed to costs related to smoking.[8] Research finds that smoking rates are highest among those with less access to education and financial resources. This lack of access may make them more susceptible to marketing strategies used by tobacco companies to encourage use of addictive products, particularly among youth.[9] Tobacco companies have historically exploited lower income and underserved communities by targeting them for “free” samples and giveaways, which in turn develop into addictions that become difficult to quit and contribute to serious health problems.[10]

Most smokers want to stop using cigarettes and have unsuccessfully tried to quit.[11] Importantly, Georgia does not provide comprehensive coverage of cessation treatments through Medicaid, although some treatments are available.[12] Lower income Georgians are less likely to be able to overcome the many barriers to quitting, requiring greater support through counseling, medications or a combination of treatments.[13] State lawmakers could address this disparity by investing more in public health and Medicaid and offering comprehensive coverage. That investment could help reduce smoking rates through no-cost cessation treatments for those who want to quit.

Since reaching a settlement agreement with four of the nation’s largest tobacco companies in 1998, Georgia has received annual payments under what is known as the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. In FY 2025, these funds amount to about $148.6 million, including $139.4 million in annual payments and $9.2 million in interest.[14] Like revenues from tobacco and vaping user fees, these funds are added to Georgia’s general fund and are freely available for appropriation without restriction.

Georgia also collects about $83.9 million in revenue from smokeless tobacco, loose tobacco and cigars. User fees on these products could be used to cover the direct costs of oral and mouth cancers, dental issues and related health expenditures that arise from other forms of tobacco use. Further research and data from the state Medicaid program could help to quantify these other costs and ensure that appropriate user fees are set to cover them.

Accounting for all user fees on cigarettes and vaping products, retail fees and the tobacco settlement agreement leaves a gap of at least $296 million in annual costs attributable to smoking among adults and teens covered by Medicaid. This demonstrates that Georgia’s tobacco revenues fail to cover even the direct annual costs of smoking paid by Medicaid. Under this policy framework, the state of Georgia is effectively asking other taxpayers to subsidize the cost of smoking.

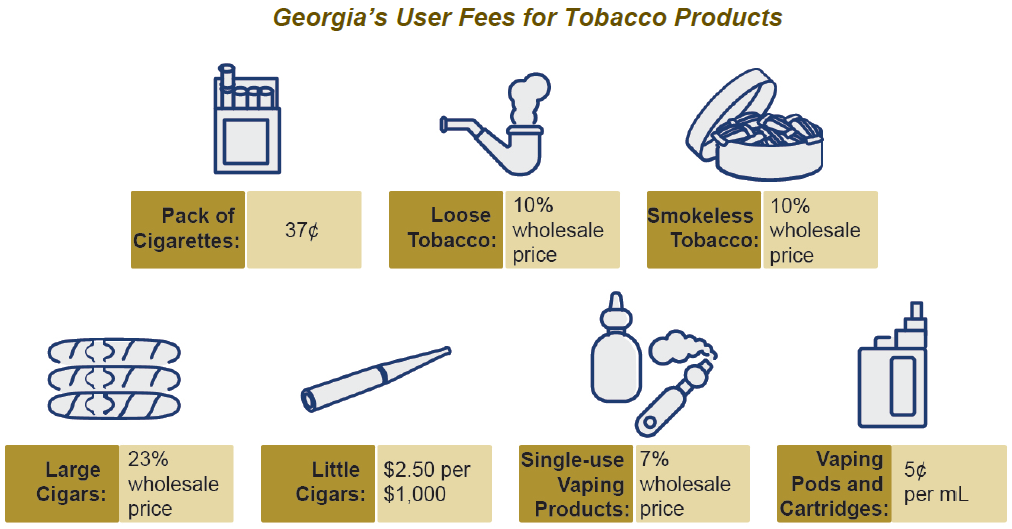

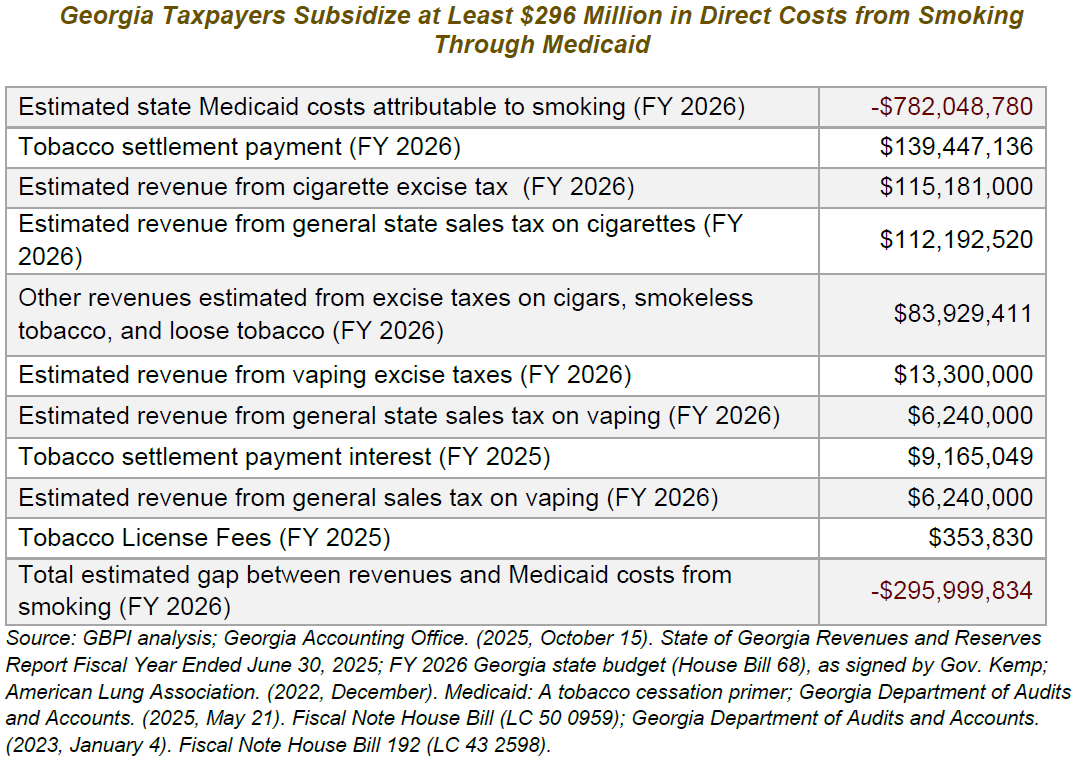

Cigarette User Fees

During the current fiscal year (FY 2026), Georgians are expected to purchase 311 million packs of cigarettes, raising about $115 million through the state’s $0.37 cigarette user fee.[15] That ranks as the nation’s second lowest state user fee per pack of cigarettes and falls far below the 50-state national average of $1.96. Like most states, Georgia also applies its 4% state general sales tax rate to the purchase of cigarettes and other tobacco products. Including both sales taxes and excise taxes on cigarettes, Georgia will collect an estimated $227 million in tax revenue in FY 2026.[16]

On average, a pack of 20 cigarettes currently retails for about $9.01 per pack, including the state’s $0.37 user fee and the federal excise tax of $1.01 per pack, which was last revised in 2009.[17] In 2003, Governor Sonny Perdue led Georgia to raise its cigarette user fee up to the current level of $0.37 per pack from the previous rate of $0.12 per pack. At the time, the average retail price for a pack of cigarettes was $3.01, with the state’s user fee equivalent to about 12% of the total cost.[18] Had Georgia’s cigarette user fee kept pace with inflation, it would be approximately $0.65 in 2025. Alternatively, a 12% state user fee would be equivalent to about $1.08 per pack today.

By any measure, Georgia’s user fee for cigarettes has failed to keep pace over the past two decades. Public health advocates recommend lifting this user fee by at least $1 at a time, avoiding a gradual phase-in to ensure that tobacco companies do not mute the effects by offering users coupons to continue smoking without bearing an increased cost. Adjusting Georgia’s $0.37 user fee to the national average of $1.96 would raise an estimated additional $453 million per year, even after accounting for reduced levels of cigarette use.[19]

Vaping Policy

Aside from cigarettes, the state of Georgia anticipates that 47.6 million milliliters of consumable vapor products will be sold in FY 2026, raising about $13.3 million in revenue on $156 million in total sales.[20] Georgia assesses two tiers of taxes on vaping products: a tax of $0.05 per milliliter for closed systems (pre-filled vapes) and a 7% tax on all other vaping products.[21] This ranks Georgia among the six states tied for last nationally, with the lowest user fees among the 33 states that assess unique excise taxes on vaping products.[22] Importantly, there is no federal excise tax on vaping products. This means that these products are taxed at significantly lower overall rates than cigarettes. For comparison, the combined current Georgia and federal excise tax on cigarettes is equivalent to about 15% of the purchase price, while the state tax on vaping products is set at less than half this level.

Nationally, states that apply unique taxes to vaping products by volume do so at a median rate of around $0.50 per milliliter. Some states also apply taxes as a percentage of wholesale costs, ranging from 7% in Georgia to 95% in Minnesota.[23] Georgia’s policymakers could model best practices in vaping policy by assessing a uniform percentage rate that keeps parity with the state’s user fee for cigarettes. If Georgia sets its cigarette user fee at the national average of $1.96, parity in its vaping user fee would be an excise tax rate of 28%, which could raise approximately $44 million annually. Other states have also demonstrated positive results in discouraging vaping, particularly among youth, by instituting bans on flavored products designed to appeal to adolescents.[24]

Licensing Fees and Public Health Policies to Reduce Smoking

Beyond user fees, Georgia can add other commonsense guardrails to discourage the sale and use of tobacco products. This year, the federal government eliminated the Office on Smoking and Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by terminating all staff, limiting the possibility of renewing grant funding through the Georgia Department of Public Health for its Tobacco Use and Prevention Program.[25] In FY 2026, Georgia budgeted $1.3 million in tobacco settlement funds for the state’s tobacco control program, along with $750,000 for its smoking Quitline. This legislative session, state leaders should prioritize appropriating additional funding for evidence-based youth prevention, smoking cession and second-hand smoke exposure services.

Georgia also maintains some of the nation’s lowest annual tobacco license fees, which are set at a combined level of $20 for retailers selling tobacco, alternative nicotine and vapor products, along with a $250 first year registration fee.[26] Last year, Georgia raised less than $354,000 from tobacco licenses and fees.[27] Lifting these fees could help address the proliferation of tobacco and vaping shops in communities across the state, while presenting another point of entry to help recoup some of the costs of smoking at-large. These fees range from the nation’s lowest rate of $6 in New Hampshire to the highest of $953 in Oregon.[28] GBPI recommends an annual retail fee of at least $120 for the sale of tobacco products, which is equivalent to the national average.[29] Although the revenue raising potential for this fee is limited, higher fees could discourage the prevalence of tobacco retailers and help reduce youth access to harmful products.

Conclusion

Looking ahead to the 2026 legislative session, policymakers have a wide menu of options to improve health outcomes and better control the substantial costs of smoking. Approximately 11,700 adults in Georgia die annually from smoking, with 29.9% of all cancer deaths attributable to smoking.[30] Over a five-to-10-year period, Georgia’s leaders should set a concrete goal to reduce the share of residents who smoke. For example, at the federal level, the Department of Health and Human Services has a target of reducing the share of adults who smoke from 11% to 6.1% by 2030.[31] At a minimum, state leaders should end Georgia’s current policy of asking other taxpayers to subsidize the cost of tobacco by raising at least $296 million in new revenues from tobacco products.

Aligning Georgia’s tobacco user fees for cigarettes and vaping products to the national average would help accomplish this goal, while instituting a disincentive to encourage smokers to quit. As tobacco use decreases, the state will reap further savings through lower health care costs and reduced direct spending on tobacco-related illness and disease through Medicaid.

Lifting Georgia’s cigarette user fee to the national average of $1.96 would raise an estimated $453 million in new revenue.[32] Doing so would put the combined state and federal user fee at approximately 28% of the adjusted price of a pack of cigarettes.[33] Establishing parity with vaping products at the same 28% rate could raise an additional $44 million in revenue—raising this total to nearly $500 million. Combining these measures with adjusting Georgia’s licensing fee on retailers of tobacco products to the national average could further help discourage tobacco use. Once these measures are in place, Georgia should include an automatic adjustment to keep pace with inflation, as the state does with motor fuel taxes, to ensure that these policies are not eroded in the future. Ultimately, reducing the share of Georgians who smoke, and in turn, reducing the amount of tobacco products sold in Georgia, will contribute to lower health care costs, improved economic productivity and a healthier state overall.

Endnotes

[1] Smith. A. (2025). House of Representatives Study Committee on the Costs and Effects of Smoking: Final report. House Budget and Research Office. https://www.legis.ga.gov/api/document/docs/default-source/house-study-committee-document-library-page/costs-effects-of-smoking/signed_costs-and-effects-of-smoking-final-report.pdf?sfvrsn=983b896f_2

[2] KFF. (2025, October 31). Adults who report smoking by sex (2024). https://www.kff.org/state-health-policy-data/state-indicator/smoking-adults-by-sex/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[3] KFF. (2025, October 31). Adolescents reporting cigarette and tobacco use in the past month (2022-2023). https://www.kff.org/state-health-policy-data/state-indicator/adolescents-reporting-cigarette-and-tobacco-product-use-in-the-past-month/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[4] Georgia Budget & Policy Institute estimate. (2025, October 31); U.S. Census Bureau, estimates of the Total resident population for the United States; Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2025, May 21). Fiscal note House Bill 83 (LC 50 0959). https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2026/lc-50-0959/download; Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2023, January 4). Fiscal note House Bill 192 (LC 43 2598). https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2023/lc-43-2598hb-192/download

U.S. Census Bureau. Population of regions, states, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: July 1, 2024 (SCPRC-EST2024-18+POP)

[5] Nargis, N., Ghulam Hussain, A. K. M., Asare, S., Xue, Z., Majmundar, A., Bandi, P., Islami, F., Yabroff, R., & Jemal, A. (2022, October). Economic loss attributable to cigarette smoking in the USA: An economic modelling study. The Lancet Public Health (7)10, e834-43. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00202-X.

[6] Beeler Asay, G. R., Homa, D. M., Abramsohn, E. M., Xu, X., O’Connor, E. L., & Wang, G. (2017, October 26). Reducing smoking in the US federal workforce: 5-year health and economic impacts from improved cardiovascular disease outcomes. Public Health Reports, 132(6), 646-653. doi: 10.1177/0033354917736300

[7] Georgia Budget & Policy Institute analysis of Georgia’s FY 2026 budget (House Bill 68), as signed by Gov. Kemp; American Lung Association. (2022, December). Medicaid: A tobacco cessation primer. https://www.lung.org/getmedia/033dbc18-aebb-4c03-b1f5-3b8599d1b9f7/medicaid-a-tobacco-cessation.pdf.pdf

[8] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, September 24). STATE system Medicaid coverage of tobacco cessation treatments fact sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/medicaid/Cessation.html; American Lung Association. (2022, December). Medicaid: A tobacco cessation primer. https://www.lung.org/getmedia/033dbc18-aebb-4c03-b1f5-3b8599d1b9f7/medicaid-a-tobacco-cessation.pdf.pdf

[9] Garett, B. E., Martell, B. N., Caraballo, R. S., & King, B. A. (2019, June 13). Socioeconomic differences in cigarette smoking among socioeconomic groups. Preventing Chronic Disease 2019, 16: 180553. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.180553

[10] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, May 15). Unfair and unjust practices and conditions harm people with low socioeconomic status and drive health disparities. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco-health-equity/collection/low-ses-unfair-and-unjust.html

[11] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, September 17). Smoking cessation: Fast facts. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/php/data-statistics/smoking-cessation/index.html

[12] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, September 24). STATE system Medicaid coverage of tobacco cessation treatments fact sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/medicaid/Cessation.html

[13] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, July 25). Adult smoking cessation – United States, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7329a1.htm

[14] Georgia Accounting Office. (2025, October 15). State of Georgia revenues and reserves report fiscal year ended June 30, 2025. https://sao.georgia.gov/press-releases/2025-10-15/fy25-georgia-revenues-and-reserves

[15] Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2025, May 21). Fiscal note House Bill (LC 50 0959). https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2026/lc-50-0959/download

[16] This figure includes $118.2 million in state general sales taxes on cigarettes, $115.2 million in excise taxes on cigarettes, $13.3 million in vaping excise taxes, and $6.2 million in state general sales taxes on vaping products.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Seaman, B. A. (2003, October). The economics of cigarette taxation: Lessons for Georgia. Georgia State University, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Fiscal Research Program. https://cslf.gsu.edu/files/2014/06/economics_of_cigarette_taxation_lessons_for_georgia.pdf

[19] Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2025, February 5). Fiscal note House Bill HB 96 (LC 59 0042). https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2025/lc-59-0042/download

[20] Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2023, January 4). Fiscal note House Bill 192 (LC 43 2598). https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2023/lc-43-2598hb-192/download

[21] Ga. Code Ann. § 48-11-2 (2024) https://law.justia.com/codes/georgia/title-48/chapter-11/section-48-11-2/

[22] Hoffer, A. (2025, June 24). Vaping taxes by state, 2025. Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/vaping-taxes/

[23] Ibid.

[24] Reiter, A., Hérbert-Loiser, A., Mylocopos, G., Filion, K. B., Windle, S. B., O’Loughlin, J. L., Grad, R., & Eisenberg, M. J. (2024, January) Regulatory strategies for preventing and reducing vaping among youth: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 66(1): 169-181. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.08.002

[25] Tagami, Ty. (2025, June 14). Lawmakers, backed by health advocates, push for increase in cigarette tax. Rough Draft Atlanta. https://roughdraftatlanta.com/2025/06/14/georgia-cigarette-tax-increase/

[26] Georgia Department of Revenue. (2025, October 31). Tobacco retailer license. https://dor.georgia.gov/tobacco-retailer; Abraham, Ann. (2024, July 19). Enhancing tobacco control through retailer licensing policies. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. https://www.astho.org/communications/blog/enhancing-tobacco-control-through-retailer-licensing-policies/

[27] Georgia Accounting Office. (2025, October 15). State of Georgia revenues and reserves report fiscal year ended June 30, 2025. https://sao.georgia.gov/document/document/fy25grrrfinalv2101525-securedpdf/download

[28] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, September 30). STATE system licensure fact sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/licensure/Licensure.html; Oregon Health Authority. (2025, November 4). Tobacco retail licensing and sales. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/preventionwellness/tobaccoprevention/pages/retailcompliance.aspx

[29] Abraham, Ann. (2024, July 19). Enhancing tobacco control through retailer licensing policies. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. https://www.astho.org/communications/blog/enhancing-tobacco-control-through-retailer-licensing-policies/

[30] Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. (2025, October 31). The toll of tobacco in Georgia. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/problem/toll-us/georgia

[31] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2025, October 31). Reduce current cigarette smoking in adults – TU 02, Healthy People 2030. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/tobacco-use/reduce-current-cigarette-smoking-adults-tu-02

[32] Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2025, February 5). Fiscal note House Bill HB 96 (LC 59 0042). https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2025/lc-59-0042/download

[33] Under this modeling, the price per pack of cigarettes would increase from an average of $9.01 to $10.60, with a state user fee of $1.96 and a federal user fee of $1.01, totaling $28% of the total cost.