Bill Analysis: Senate Bill 405 (LC 21 5954 S, AM 21 3929)

Georgia needs more people with higher education to meet workforce needs. Georgia can better leverage its talent and its strong colleges and universities by knocking down financial barriers to student success and making common-sense investments in financial aid.

The Georgia Senate recently passed a proposal to authorize a new grant for college students that gives weight to financial need, as well as academic and work requirements. Senate Bill 405 proposes a maximum $1,500 grant per semester for full-time, University System of Georgia college students whose family incomes do not exceed $48,000, as long as they meet these requirements:

- Receive the need-based federal Pell Grant

- Do not receive the HOPE Scholarship

- Earn a high school or college GPA ranging from 2.3 to 2.99

- Meet ACT, SAT, Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate benchmarks, pass an end-of-pathway assessment, or complete a work-based learning experience

- Work at least 15 hours per week, with an exemption for student athletes during competition semesters

The Georgia Student Finance Commission would administer payments to schools. The plan is to assign each school a budget based on a formula that accounts for a school’s tuition, fees, number of Pell and HOPE recipients and average Pell award. Schools certify students’ eligibility under the plan.

The bill establishes the new grant’s eligibility and structure, though lawmakers retain the ability to appropriate funds. An estimated 16,700 students might qualify for the grant at a cost of $25 million in the first year, according to the Department of Audits and Accounts. Administrative costs could amount to $1.1 million more. Total program costs are expected to gradually increase and cover 21,700 students by 2022.[1]

SB 405 Combines Aspects of Need-Based and Merit-Based Financial Aid

The proposed grant is best described as hybrid of need- and merit-based aid. Need-based aid weighs a family’s ability to pay for college costs to determine eligibility. It also requires GPA and credit accumulation benchmarks, or Satisfactory Academic Progress, to show progress towards a degree. Merit-based aid rewards academic performance alone, such as high test scores or grades. Much financial aid falls in between the two. Twenty states offer a hybrid of merit- and need-based aid that requires students to demonstrate financial need and also meet academic requirements.[2]

Financial Need is High Among Georgia’s College Students

Georgia is home to many hardworking students who cannot afford to go to college without financial aid. Forty-three percent of undergraduate students in the university system and 48 percent of Technical College students qualify for the Pell Grant, mostly awarded to families earning less than $30,000 per year.[3] But the Pell Grant covers only a fraction of most students’ college costs. About 112,000 of Georgia’s university system students have unmet financial need beyond grants and loans.[4] Every year an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 students in the university system and technical colleges register for classes but drop out because they can’t pay tuition and fees.[5]

Financial need tends to be highest at lower-cost technical colleges, state colleges and state universities. Enrollment at schools with a large share of students with financial need tends to fluctuate the most with economic downturns and tuition increases. Even a slight change in tuition or grants can create large enrollment swings in these schools.

The vast majority of Georgia’s financial aid is awarded through the HOPE programs, the largest merit-based state aid program in the country. But Georgia is one of only two states that lack broad need-based financial aid.[6] Students often face financial roadblocks to completing their degrees. Financial aid increases the likelihood of college enrollment[7] and can deliver longer-term benefits, including greater student persistence and completion. [8] For example, Florida’s need-based grant increased the probability of a student earning a bachelor’s degree by 4.6 percentage points.[9]

State Aid Should Knock Down Financial Barriers and Encourage College Completion

Any new state aid in Georgia should be guided by two primary goals:

- Clear pathways for students with the greatest barriers to a college degree, including low-income students, first-generation students and black and Hispanic students

- Encourage college completion

1. Clear Pathways for Students with the Greatest Barriers to a College Degree

The aim of SB 405 is to help full-time students in the university system who do not receive HOPE. Lawmakers might also consider including other types of students, including technical college students, part-time students and low-income HOPE scholars. Nearly 64,000 low-income technical college students receive the Pell Grant.[10] About 95,000 university system students attend part-time.[11] And 35,000 university system students receive both Pell and HOPE.[12]

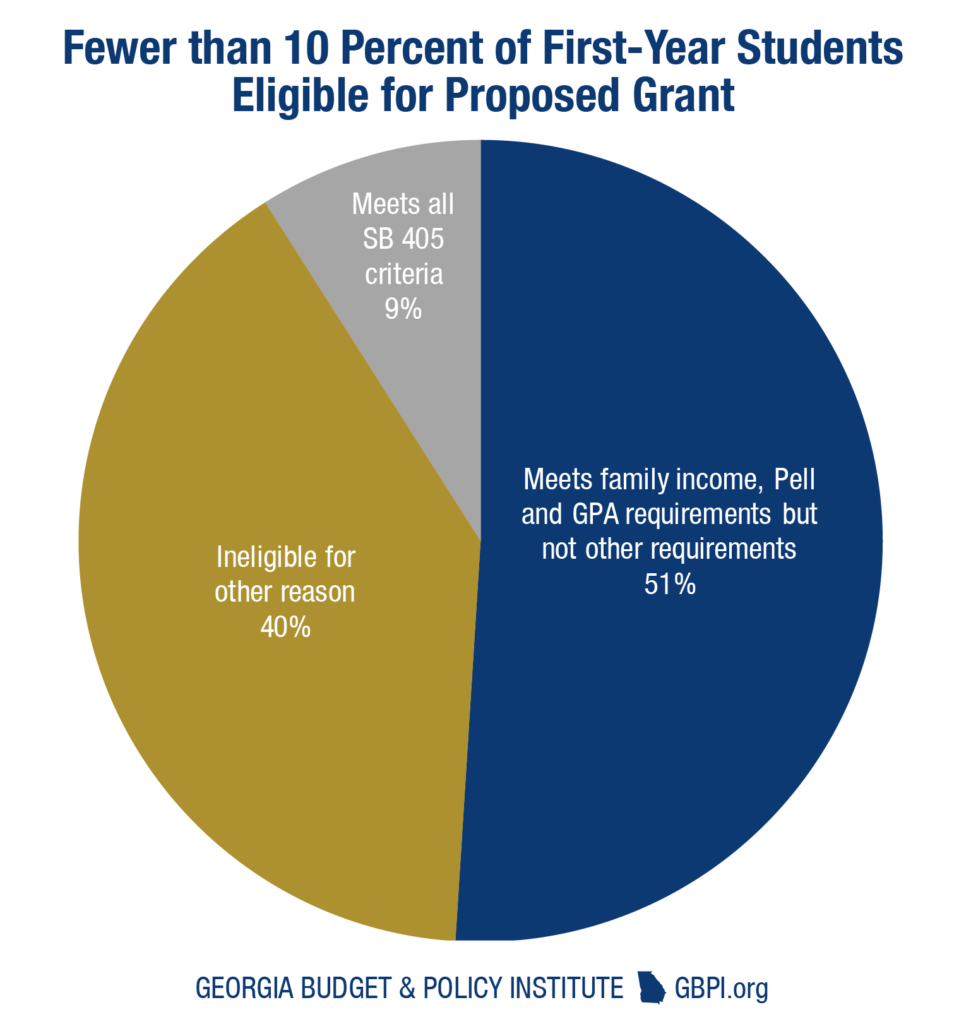

Sixty percent of first-time students qualify under the proposed family income, Pell and GPA requirements, according to the state auditors. However, only 15 percent of these students qualify under the proposed standardized test and other requirements, for a total of 9 percent of first-year students.[13]

The proposed income requirements and grant size can be better tailored to fit students’ varying financial needs. The proposed $48,000 family income cap factors in a family’s ability to pay and directs more money to lower-income families to partially offset the fact that most state financial aid dollars go to middle and high-income families. To further target financial aid dollars, it can use federal formulas that factor in family size. This information is available through the federal form used to calculate Pell Grant eligibility.

Grant amounts can also be pegged to financial need. The bill proposes a maximum $1,500 grant, and school grant budgets vary by tuition, fees, number of Pell and HOPE recipients and average Pell award. To vary individual grant amounts, to the formula can tie the award’s size to the Pell Grant the student receives. For example, set the Georgia award at 25 percent of the Pell Grant, and assuming that grant is $3,000, the student receives a Georgia award of $750.

2. Encourage College Completion

The bill includes a 15-hour weekly work requirement, with an exception for student athletes. Though many students choose to work based on their financial, academic and life needs, requiring work might impede college completion goals. Working more than 20 hours a week reduces a student’s odds of completing a degree by 19 percent, compared to those who did not work.[14]

Many students have legitimate reasons not to work as much as 15 hours per week. Some might put in hours without pay in family caretaking roles. Others might rather develop relationships with faculty, mentors and other students, and engage in career-related extracurricular activities. Students who take part in clubs their first year of college increase chances of degree completion by 39 percent over students who do not.[15] Unless the job pays well or boosts career opportunities, many students might be better served to focus more on their education. Removing or reducing the work requirement provides more flexibility for a variety of circumstances.

One strategy to promote the benefits of work without requiring it is to expand access to work-study programs. Completion rates for students attending public colleges get a boost from work-study jobs because they offer distinct advantages over other jobs, according to federal research. Most jobs are on-campus, easing transportation and scheduling conflicts. Positions can be connected to students’ academic interests and desired professional skills. And unlike wages from other jobs, work-study earnings are not counted against federal aid calculations. Instituting a work requirement without increased funding for work-study opportunities might be counterproductive for some students. Fourteen states fund their own work-study programs, leveraging state money to provide incentives for employers to hire student workers.

Conclusion

Legislative momentum to provide state need-based financial aid creates an opportunity to build a more prosperous state by supporting more students to graduation. The proposed SB 405 can be strengthened to help more students, but it offers a first step towards policies that invest in degree completion, boost the economy, and empower more Georgians on their chosen education and career paths.

More details on how Georgia can better support students and their families through state aid are available in GBPI’s January 2018 report “Strengthen Georgia’s Workforce by Making College Affordable for All.”

Endnotes

[1] Department of Audits and Accounts. (2 Feb 2018). Fiscal note, LC 21 5937. https://opb.georgia.gov/2017-2018-regular-session

[2] Education Commission of the States. (2017). 50-state policy database. http://statefinancialaidredesign.org/state-financial-aid-database/

[3] University System of Georgia and Technical College system of Georgia 2017 enrollment reports

[4] University System of Georgia data, 2014-15

[5] Community Foundation of Greater Atlanta. (2018). College access and affordability for all Georgians. [Powerpoint slides].

[6] National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs. 47th annual survey report on state-sponsored student financial aid. 2015-2016 academic year. http://nassgap.org/survey/NASSGAP%20Report%2015-16_2.pdf

[7] Dynarski, S., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2013). Financial aid policy: Lessons from research. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

[8] Castleman, B.L., & Long, B.T. (2013). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

[9] Castleman, B.L., & Long, B.T. (2013). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

[10] Technical College system of Georgia 2017 enrollment report

[11] University System of Georgia 2017 enrollment report

[12] University System of Georgia data.

[13] Department of Audits and Accounts. (2 Feb 2018). Fiscal note, LC 21 5937. https://opb.georgia.gov/2017-2018-regular-session

[14] National Center for Education Statistics. (2012). Higher education: Gaps in access and persistence study. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012046/chapter8_4.asp

[15] National Center for Education Statistics. (2012). Higher education: Gaps in access and persistence study. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012046/chapter8_4.asp