During the 2018 legislative session, the Georgia Legislature passed House Bill 787 with a provision authorizing the Georgia Student Finance Commission to create the state’s first broad need-based aid program for university system students. Critical next steps include deciding the structure of a need-based aid program and adequately funding it. Lawmakers now have the opportunity to create a more prosperous and competitive state by helping hardworking Georgians who face financial barriers complete their degrees.

Georgia led the nation on student financial aid with the HOPE scholarship, providing greater access to college—one of the best engines to propel low-income students into the middle class. Recent legislation bolsters that foundation and offers an opportunity to build on HOPE’s success. Funding need-based aid and ensuring its effective implementation will expand and strengthen Georgia’s financial aid portfolio by investing in college credentials, skilled workers and a competitive workforce. Georgia needs more people with higher education. Low-income students drove college enrollment growth, yet colleges and universities struggle to support them to graduation. Our state cannot afford to leave these students behind.

In a few short years, more than 60 percent of Georgia jobs will require some postsecondary education.[1] Georgians with a bachelor’s degree earn nearly $17,000 more than those with some college or an associate degree and in excess of $22,000 more than those with a high school diploma only.[2] But many are not prepared to meet future job requirements. And financial challenges create roadblocks for many students working toward a postsecondary credential. Each year, Georgia colleges drop students by the thousands because they cannot pay their tuition and fees. Even more students struggle to graduate because the financial challenges of paying for college overwhelm their ability to perform well in school. These students miss out on the job opportunities that come with a postsecondary credential. Though students across various family income and racial/ethnic classifications struggle with college costs, evidence shows that black students lack access to state financial aid and take on heavy debts to finance their education.

Georgia is poised to strengthen its financial aid strategy by targeting support for low-income students that includes HOPE and need-based aid and maximizes the number of students graduating with college credentials from all walks of life. Nationwide, states award an average of $624 in need-based aid per student. If Georgia committed the national average per-student amount to university system students, it would cost $169 million.[3] The state today fails to fully leverage its most powerful economic asset—its own people. Georgia cannot serve only some college students well, continue to fulfill a growing state’s workforce needs and enjoy a prosperous economy statewide. Georgia needs a people-first strategy to build a stronger, more inclusive economy.

To Meet Workforce Demands, Georgia Must Graduate More Low-Income Students and Students of Color

Georgia colleges produce fewer graduates than necessary for future job requirements. More than 60 percent of Georgia jobs will require some postsecondary education by 2025.[4] Recent data show 48 percent of the state’s young adults have postsecondary credentials.[5]

About 34,000 students enrolled in Georgia’s public university system as first-time, full-time college freshmen in Fall 2012. Today only 61 percent, or fewer than 21,000, graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the university system.[6] Thousands more enroll as part-time or returning students and face long, challenging paths to graduation. To meet workforce needs, Georgia will need to improve upon its graduation rate.

Though the state can improve the way it supports college students from all family backgrounds, students from low income families will benefit the most from support that continues to graduation. College enrollment often follows years of unequal education opportunities linked to family income. But even with similar levels of academic preparation and achievement, financial insecurity creates challenges for many students. Paying for tuition, fees, books, transportation and other living expenses while balancing the need to work and focus on school poses obstacles to students’ academic careers. These challenges show up in graduation rates.

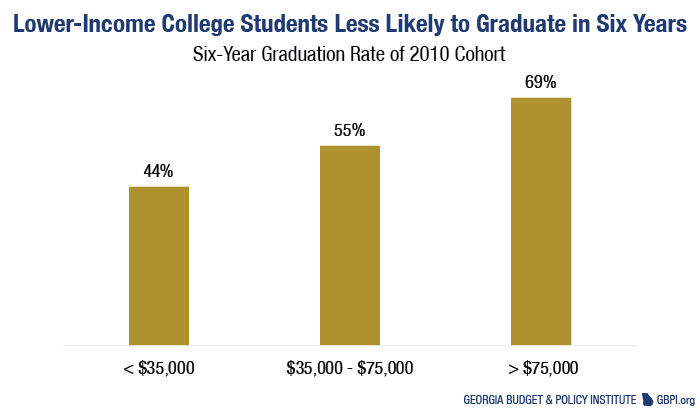

Fewer than half of freshmen from families earning less than $35,000 per year will graduate with a bachelor’s degree within six years. Almost 70 percent of students from families earning more than $75,000 a year will graduate.[7] Students who qualify for the federal need-based Pell Grant graduate at rates nearly 20 percentage points lower than their fellow students who do not receive the grant.[8] Though Pell Grants help many students, they have not kept up with student financial need. Even after Pell Grants, the university system estimates more than 112,000 students experience a gap between available financial resources and college costs.[9]

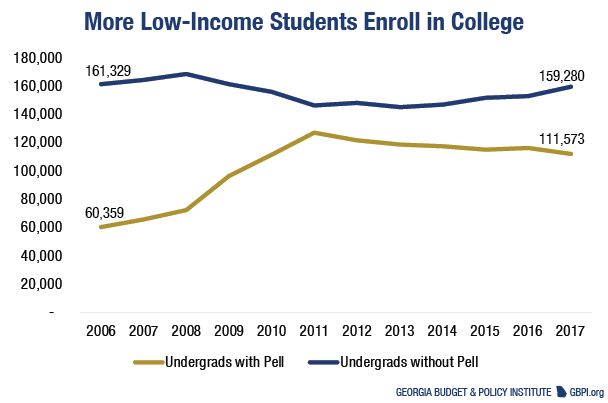

Graduating enough skilled workers depends on the success of the state’s low-income students. Eighty-five percent more students who qualify for the Pell Grant enroll in the university system today than 10 years ago. Student enrollment of those not qualifying for the Pell Grant stayed almost the same.[10] If more low-income students enroll in college but state policies do not support low-income students to graduation, Georgia will not produce enough workers with postsecondary education to fuel future economic growth. Worse, thousands of students’ potential goes untapped.

The same analysis holds true for race and ethnicity. In the past five years, enrollment by Hispanic/Latino students increased by 41 percent, while total undergraduate enrollment increased by 2 percent. Without increased enrollment from Hispanic students, the university system’s total enrollment would have declined.[11] But large racial and ethnic disparities persist in graduation rates. Overall the university system sees a nearly 20 percentage-point difference in the bachelor’s degree graduation rates between white and black students.[12] Though a few schools closed graduation gaps between student groups by race and ethnicity, a number of schools that serve many students of color still struggle to lower barriers. As Georgia’s college students become more diverse by race, ethnicity and family income, graduation gaps will weaken the state’s ability to educate its people and provide a skilled workforce. Georgia cannot afford to leave low and middle-income students and students of color behind.

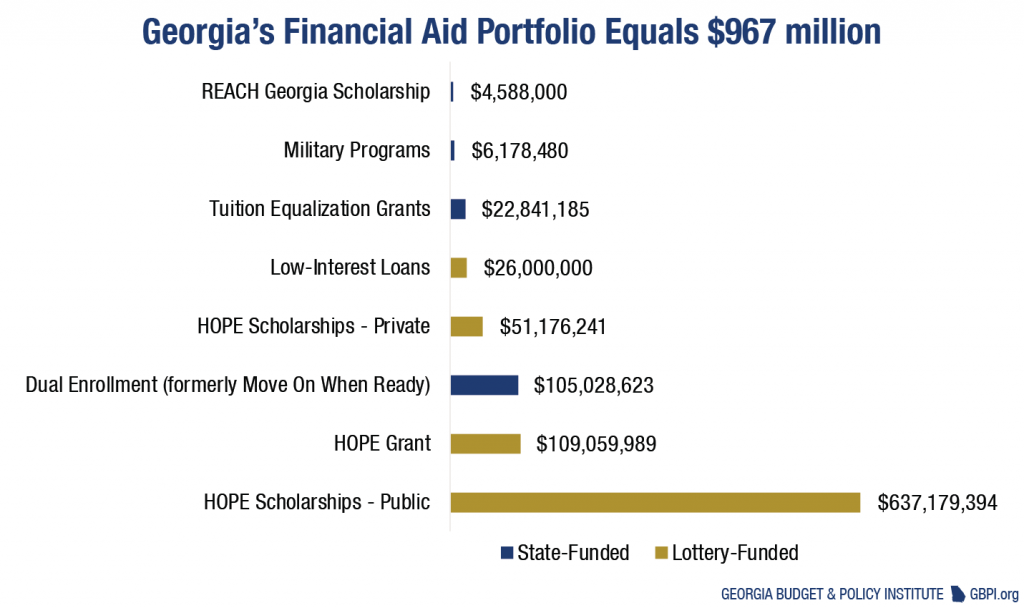

State Financial Aid Portfolio Lacks Targeted Support for Low-Income Students

Current state financial aid policy leaves out many low-income students and schools that serve them. HOPE Scholarships dominate Georgia’s financial aid portfolio. It is the largest state merit-based aid program in the country, and many low-income students receive HOPE scholarships and grants.[13]

HOPE helped a generation of Georgians pay for college, but the program is no longer sufficient for the state’s needs. The scholarship used to pay full tuition, fees and books for all qualifying students. But in 2011 the Legislature reduced the scholarship to cover partial tuition, cut the fee and book award and restricted eligibility for the full-tuition scholarship. The higher education landscape also changed in important ways since the state created the scholarship 25 years ago. These changes include soaring student enrollment, low-income student enrollment growth, public funding decline and college tuition increases.

Most state financial aid dollars benefit students at only a few universities. Fifty-four percent of all HOPE dollars in the university system go to students attending three schools: the University of Georgia, Georgia State and Georgia Tech.[14] Institutional need-based scholarships, or scholarships that schools award from privately raised funds, are also concentrated in student populations attending these universities.[15] In contrast, 16 percent of HOPE dollars go to students attending state universities like the University of North Georgia, Middle Georgia State and Savannah State. These schools with fewer resources and who serve larger numbers of low-income students receive fewer HOPE dollars and struggle to raise money for private need-based scholarships for their students.

Large racial and ethnic differences exist in who receives state aid as well. In Fall 2017, 29 percent of undergraduates in the university system were black/African-American, yet only 20 percent of HOPE recipients were.[16] HOPE requires a 3.0 GPA and four academically rigorous courses such as Advanced Placement. Black students in Georgia are much more likely to attend high-poverty schools that experience challenges such as less experienced teachers and high teacher and principal turnover. These challenges undermine student academic success.

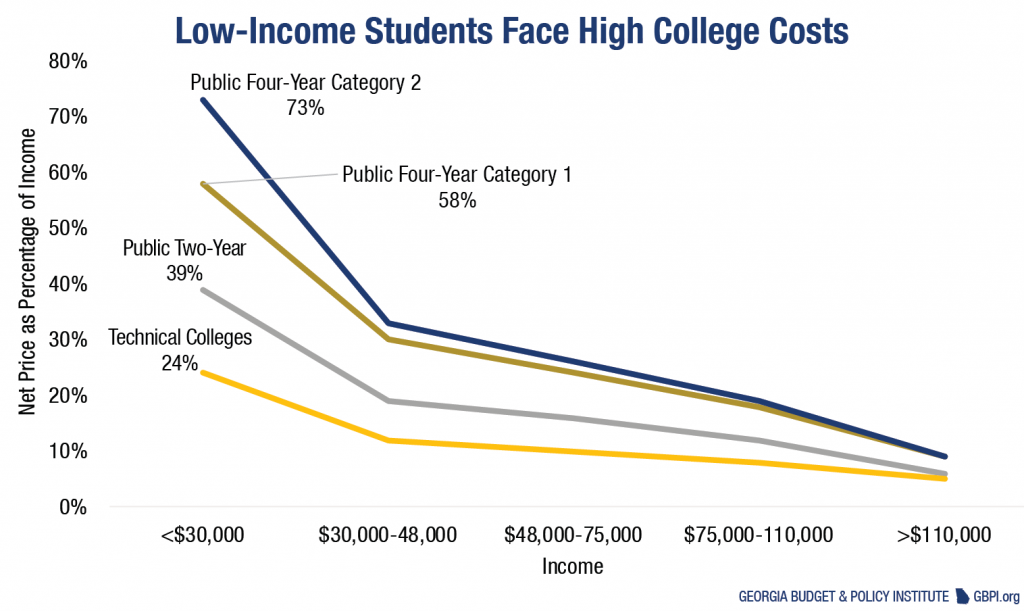

While many low-income students choose to attend lower-priced schools, costs are still high relative to their resources, even after accounting for financial aid. The net costs of most Georgia colleges are more than half of the income for students whose family earns less than $30,000, according to analysis by the Southern Regional Education Board: this is a quarter of all Georgia families.[17]

The lack of state need-based aid leaves the federal government as the primary, and often only, source of financial resources for low-income students through Pell Grants. Though Pell Grants help many students, they can still leave a large financial gap. Today, the maximum Pell Grant covers 29 percent of the average cost to attend a public four-year college. It covered 42 percent in 2001.[18] The university system estimates that even after Pell Grants and federal loans, more than 112,000 students have unmet financial need totaling more than $808 million, or $7,198 per student.[19]

The lack of state need-based aid also leaves students more dependent on loans, which enable them to attend college in the short-term but can hamper financial security in the long-term. About half of undergraduates will take out federal loans to pay for college, borrowing on average $7,774 in one year.[20]

“Black families, on average, have seven times less wealth than white families and are more likely to turn to loans to finance college.” [21]

Student loan debt places a very heavy burden on black students. National data show that black students have the highest borrowing rates and debt loads in both private and public two and four-year colleges.[22] Black families, on average, have seven times less wealth than white families and are more likely to turn to loans to finance higher education.[23] Past and present policies and behaviors that discriminated against African-Americans contribute to this disparity. In Georgia’s university system, the three schools with the highest borrowing rates are historically black colleges: Fort Valley State, Savannah State and Albany State. Most students at these schools take out federal loans to help pay for college, averaging more than $9,000 in loans per year.[24]

A College Degree Can Launch Students to the Middle Class

High costs block students from college, one of the best engines to launch low-income students into the middle class. Researchers analyzed millions of individual tax records and compared students’ family incomes before college and the students’ incomes in their early 30s. The study found that college can be a powerful tool for changing the trajectory of students’ lives. When students from low-income families attended college, they earned similar salaries as their higher-income peers afterward.[25]

A few high-priced and resourced schools like Georgia Tech and Emory were most successful in boosting their lower-income students up the economic ladder. Students whose family incomes were in the bottom 60 percent before college were top earners by their early 30s. But these schools serve a relatively small number of low-income students statewide. Georgia’s historically black colleges and universities, like Albany State, Clark Atlanta, Fort Valley State and Spelman College have best balanced serving many low-income students and propelling them up the economic ladder.[26]

Schools that serve many low-income students tend to get much less state funding. Most Georgia public colleges get about half of the per-student funding as the University of Georgia and Georgia Tech.[27] Following long-term cuts to public funding and associated increases in tuition and student financial need, many Georgia schools struggle today with high student borrowing rates, low graduation rates and gaps in graduation rates between low-income and higher-income students.

In addition to direct student aid, the state should also continue to support strong funding to colleges and universities so that schools can support students to graduation. Research shows that in less selective colleges, state spending has large effects on graduation rates. With more resources, these schools increase academic services, like advising and tutoring, which support students to graduation.[28] System-wide initiatives that focus on campus practices such as Momentum Year and campus-level experimentation around High-Impact Practices, innovative data and technology use and rethinking advising models should continue. Smart investments in need-based aid can supplement these efforts.

Need-Based Aid is One Tool Georgia Lacks to Support College Completion

Money matters for college students throughout their college careers: the decision to enroll,[29] the ability to persist without gaps in enrollment and completing a degree. Evidence suggests for every $1,000 in HOPE scholarship aid, Georgia’s college enrollment rate increased by 4 percentage points.[30] A Wisconsin study found that for every $1,000 increase in total financial aid, the probability of persistence between the first and second years of college rose by 3 to 4 percentage points.[31] A recent study of Florida’s need-based grant found that an additional $1,000 in grant aid increased bachelor’s degree attainment by 4 percentage points, 22 percent.[32]

Students who received both a need-based and merit-based scholarship completed bachelor’s degrees at rates 9.1 percentage points higher than those who qualified for the merit-based award only. Students with more financial aid work less, do better in school and earn college credit faster.

“In Florida, students who received both a need- and merit-based scholarship graduated at rates 9.1 percentage points higher than those who qualified for the merit-based award only.” [33]

College students’ financial need is high and hurts their academic careers. About 70,000 Georgia high school graduates will enroll in college within 16 months of graduation. Forty-two percent of those students qualified for free or reduced lunch during high school.[34] When students go from high school to college, they transition between a mostly free system to one with high costs not only for tuition and fees, but often for housing, food, transportation and books. Forty-two percent of college students did not receive financial support from their parents to help pay for college, according to a recent survey.[35]

Every semester colleges drop thousands from classes because they can’t pay tuition, not because they fail their academic requirements. Thousands more underperform because they lack secure housing and food, consistent transportation or money for books. Fifty-four percent of Georgia college students face food or housing insecurity, meaning they struggle to pay for food, rent or utilities. Many students underperform because they work many hours to pay for tuition and make ends meet.

Nearly 60 percent surveyed have one or more jobs and work on average 24 hours per week. Work does not correlate with financial security: the more hours students work, the more likely they report being food or housing insecure.[36] Many students find themselves in situations like Elton’s, where the necessity to work and pay for living costs conflicts with doing well in school:

“My first couple of years I struggled with paying my expenses. I decided to get a job as a server at a Mexican restaurant called Tlaloc. I worked there for a couple months during the week and weekends when I started to notice an impact on my grades. I saw myself struggling to maintain my grades and eventually my GPA started to decline. I honestly believe that it was a trade-off between having to work to pay off bills or spend more time to study and excel in school. Once I noticed that my grades were taking a toll I had to quit my job and focus mostly on school. I lost the HOPE scholarship, which paid 80 percent of my tuition, because I was not performing well in school and that made it more difficult on me. I realized that I had to do one or the other and that by doing both work and school at the same time I would not perform to my full potential and succeed.”

Georgia lacks a comprehensive financial aid strategy for supporting low-income students to succeed in college. Need-based aid, which uses a family’s ability to pay to determine initial eligibility, can take many forms, including grants, work-study and loans. Georgia funds need-based Student Access Loans and a small hybrid need-merit scholarship called REACH but lacks state need-based work-study. The state needs a different approach to meet today’s higher education challenges and a changing economy’s demands for college-educated workers.

Conclusion: Fund Need-Based Financial Aid

In the January 2018 report “Strengthen Georgia’s Workforce by Making College Affordable for All: Six Proposals to Build on HOPE’s Foundation,” GBPI states two principles to guide higher education investments into state aid. First, state aid should help clear pathways for students with the greatest barriers to a college degree, including low-income students, first-generation students and black and Hispanic students. Second, state aid should facilitate college completion.

Need-based financial aid is one tool to support more students to graduation—and more low-income students to the middle class—that follows these principles. Nationwide, states award an average of $624 in need-based aid per student. If Georgia committed the national average per-student amount to university system students, it would cost $169 million.[37] Though the university system depends on low-income students for enrollment, they face high college costs that make it less likely they will graduate. Need-based aid would help many promising students finish their degrees. It would also help fulfill workforce demands for a growing state.

This report is part of an ongoing series of work tied to GBPI’s People-Powered Prosperity initiative, a comprehensive vision for how Georgia lawmakers can bolster support for educated youth, a skilled workforce, thriving families and healthy communities. A statewide poll conducted earlier this year showed 82 percent of Georgians support funding need-based aid. Learn more at gbpi.org/peoplefirst.

Endnotes

[1] Carnevale, A.P., Jayasundera, T., & Gulish, A. (2016) America’s divided recovery: College haves and have-nots. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wpcontent/uploads/Americas-Divided-Recovery-web.pdf

[2] 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table B20004. Median earnings by educational attainment for the population 25 years and over.

[3] National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs. 48th annual survey report on state-sponsored student financial aid. 2016-2017 academic year. https://www.nassgapsurvey.com/survey_reports.aspx The average is calculated as total awards divided by total students and does not represent the average size of the award received. Assuming 271,000 undergraduates enrolled.

[4] Carnevale, A.P., Jayasundera, T., & Gulish, A. (2016) America’s divided recovery: College haves and have-nots. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wpcontent/uploads/Americas-Divided-Recovery-web.pdf

[5] University System of Georgia, Complete College Georgia. https://www.completegeorgia.org/

[6] University System of Georgia, Graduation Rate Reports. Bachelor’s Degree Six-Year Rates for First-Time, Full-Time Freshmen, Fall 2012 Cohort. https://www.usg.edu/research/usgbythenumbers

[7] University System of Georgia. First-time, full-time degree-seeking freshmen. Fall 2010 cohort. BA degree six-year rates.

[8] University System of Georgia data

[9] University System of Georgia data

[10] GBPI analysis of University System of Georgia data. Pell Grant awards are used as a proxy of low-income students; not all eligible students receive Pell; 80 percent of Pell Grant recipients are from families earning less than $40,000 per year.

[11] GBPI analysis of University System undergraduate enrollment data, 2014-2018. https://www.usg.edu/research/usgbythenumbers

[12] University System of Georgia, Graduation Rate Reports. Bachelor’s Degree Six-Year Rates for First-Time, Full-Time Freshmen, Fall 2012 Cohort. https://www.usg.edu/research/usgbythenumbers

[13] University System of Georgia data.

[14] GBPI analysis of Georgia Student Finance Commission data.

[15] GBPI analysis of University System or Georgia data. See also https://gbpi.org/2018/need-based-aid-complements-school-scholarships-helps-fill-financial-holes-for-college-students/

[16] University System of Georgia data

[17] Southern Regional Education Board. (November 2018). Georgia College Affordability Profile. https://www.sreb.org/state-affordability-profiles. Public Four-Year Category 1 include Georgia Tech, Georgia State and University of Georgia. Public Two-Year include Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College, Darton State, Atlanta Metropolitan, Bainbridge State, College of Coastal Georgia, East Georgia State, Georgia Highlands, Gordon State, Georgia Perimeter, South Georgia State and Georgia Military College. All other university system schools are considered Public Four-Year Category 2.

[18] Protopsaltis, S., & Parrott, S. (2017). Pell Grants. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[19] University System of Georgia data.

[20] University System of Georgia data.

[21] Urban Institute. (2017). Nine charts about wealth inequality in America. http://apps.urban.org/features/wealth-inequality-charts/

[22] GBPI analysis of data from U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2016 Undergraduates. https://nces.ed.gov/datalab/index.aspx

[23] Urban Institute. (2017). Nine charts about wealth inequality in America. http://apps.urban.org/features/wealth-inequality-charts/

[24] University System of Georgia data.

[25] Chetty, et. al. (2017). Mobility report cards: The role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/ See also https://gbpi.org/2018/overlooked-colleges-often-a-springboard-to-middle-class/

[26] EARN analysis of data from Chetty, et. al. (2017). Mobility report cards: The role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/ See also https://gbpi.org/2018/overlooked-colleges-often-a-springboard-to-middle-class/

[27] GBPI analysis of FY 2019 University System budget and Fall 2018 FTE.

[28] Deming, D.J., & Walters, C.R. (2017). The impacts of price and spending subsidies on U.S. postsecondary attainment. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/ddeming/files/DW_Aug2017.pdf

[29] Dynarski, S., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2013). Financial aid policy: Lessons from research. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w18710

[30] Dynarski, S. (2000). Hope for whom? Financial aid for the middle class and its impact on college attendance. National Tax Journal: 53, 2, part 2. https://www.nber.org/papers/w7756.pdf

[31] Goldrick-Rab, S., et. Cal. (2012). Need-based financial aid and college persistence: Experimental evidence from Wisconsin.

[32] Castleman, B.L., & Long, B.T. (2013). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

[33] Castleman, B.L., & Long, B.T. (2013). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

[34] The Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, Downloadable Data, Postsecondary C11 Report, 2016-17. https://gosa.georgia.gov/downloadable-data

[35] The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. (2018, Oct 15). Basic needs security among students attending Georgia colleges and universities. https://hope4college.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/GeorgiaSchools-10.16.2018.html

[36] The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. (2018, Oct 15). Basic needs security among students attending Georgia colleges and universities. https://hope4college.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/GeorgiaSchools-10.16.2018.html

[37] National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs. 48th annual survey report on state-sponsored student financial aid. 2016-2017 academic year. https://www.nassgapsurvey.com/survey_reports.aspx The average is calculated as total awards divided by total students and does not represent the average size of the award received. Assuming 271,000 undergraduates enrolled.