Key Takeaways:

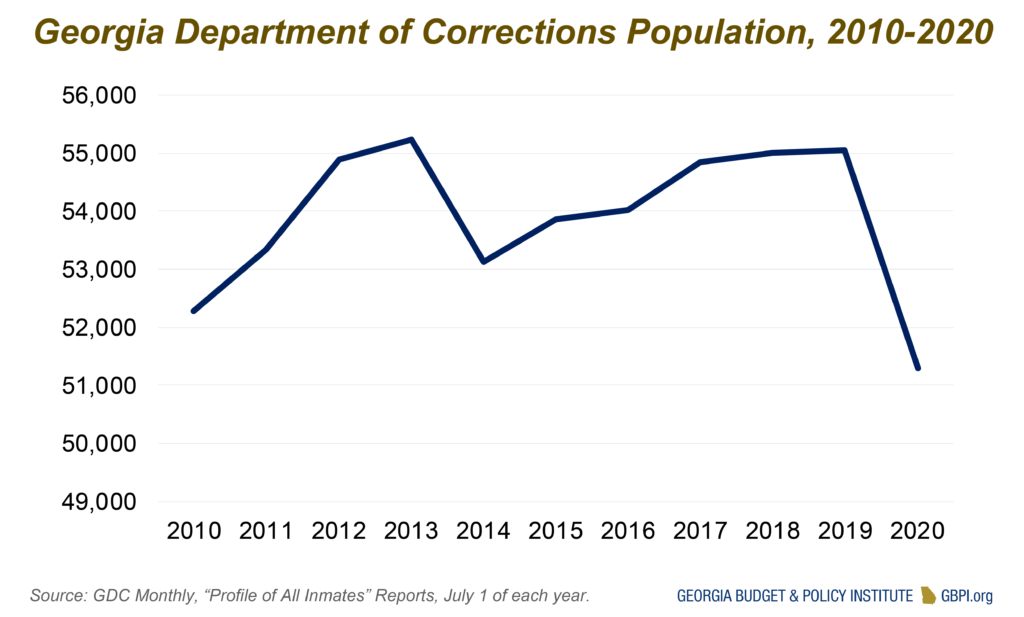

- Prior to the pandemic, the GDC population was rising, leaving those within densely populated facilities particularly vulnerable to the spread of COVID-19.

- The GDC is not tracking COVID-19 cases or fatalities by race/ethnicity, making it difficult to identify how racially disparate health outcomes are experienced in confinement.

- 38 percent of people who are incarcerated in Georgia suffer from a chronic condition that puts them at a higher risk of experiencing complications from the coronavirus.

Six months into the coronavirus pandemic, the virus has ravaged lives and the economy. While most of our focus has centered around the prevalence of the virus statewide, less attention has been specifically extended to the spread of COVID-19 within Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) facilities.

Over the last decade, Georgia has adopted a number of legislative changes to address the projected increase in the prison population and in state spending on corrections. Whether those policy changes have yielded meaningful outcomes, however, remains to be seen. The pandemic has further exacerbated the need to reduce the population of people who the state incarcerates and in turn reduce the GDC’s budget. The inability to social distance and limited access to personal hygiene products make correctional facilities prime breeding grounds for the acquisition and transmission of the coronavirus. And, given the economic effects of the virus on state revenues and the resultant steep budget cuts, reduced spending in corrections could help fill gaps in other key areas like education or child welfare.

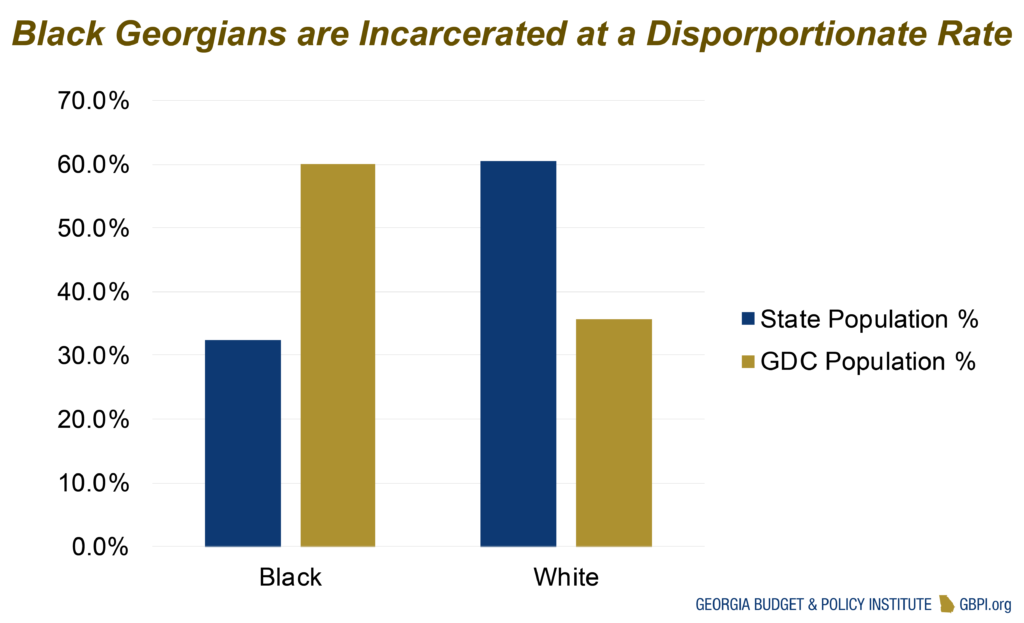

The pandemic has underscored the racial equity issues that put communities of color—particularly Black Georgians—at higher risk of contracting and dying because of the virus. Notably, despite representing only 32.4 percent of Georgia’s total population, Black Georgians comprise almost 60 percent of the state’s prison population. Black communities are over-policed and disparately impacted by the legacy of racist laws that have led to harsher sentences and over incarceration. The GDC is not tracking coronavirus cases or fatalities by race or ethnicity. Given the statewide case trends and the overrepresentation of Black people within facilities, it is vital that the agency disaggregate their case data. Without doing so, the GDC is choosing to further ignore racial inequities experienced by those in their custody.

Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC)

Although there are many entities responsible for maintaining the state’s criminal legal system, the GDC is tasked with the largest share of those duties and therefore provided with the greatest amount of funding to accomplish their tasks.[1] Individuals in GDC custody are supervised within one of the following types of facilities: state prisons, pre-release centers, county prisons, transition centers, inmate boot camps, private prisons, diversion centers, detention centers, probation boot camps, parole revocation centers or residential substance abuse treatment centers. At the beginning of the 2020 fiscal year, the population of individuals in GDC custody was 55,047.

GDC Population and the Budget

State spending on corrections exponentially increased between the 1990s and early 2000s when “tough on crime” policies were implemented both at the state and national level. During this period of time, the GDC budget ballooned from $478.5 million dollars to $1.1 billion dollars, and the prison population skyrocketed along with it from approximately 23,000 people to 52,000 people. The need to reduce state correctional spending and in turn the prison population prompted the Georgia Legislature and then-Governor Nathan Deal to enact a number of reforms to the criminal legal system beginning in 2012.

In the years that immediately followed these reform efforts, the GDC did experience a stabilization in the growth of their budget as well as a modest, short-term decrease in the commitment rate, sentencing length and total time-served for crimes whose sentencing criteria was modified. But, beginning in 2015, the GDC population began to incrementally increase, and the population rose from 53,131 in 2014 to 55,047 in 2019.[2] As the coronavirus pandemic began, the GDC reported a population of 55,025 people as of March 1, 2020. Those numbers, however, began to dip in the months that followed. Between the start of the pandemic to July 1st, the GDC population decreased by 3,734 or 6.8 percent, for a total of 51,291.

While the decline in the GDC population during the pandemic may appear promising, it should be met with substantial skepticism as to the long-term sustainability of this progress. The bulk of nationwide prison population declines are largely due to the temporary halt on transfers from county jails to avoid the spread of COVID-19 within facilities, court closures reducing the number of people being sentenced to prison and parole officers sending fewer people inside for low-level violations. With this in mind, we can assume that any gains made in reducing the prison population during the pandemic will likely be reversed once the precautionary measures are removed. The GDC population was rising before the pandemic began, which should prompt the Legislature to examine the impact of the reforms passed in 2012 and further consider steps that can be taken to ensure long-term, sustained population declines.

Correctional spending in Georgia has hovered around $1-1.2 billion dollars since 2007, even after the 2012 justice reform measures were implemented.

COVID-19 Risks Within GDC Facilities

Data collection during the pandemic has shed light on the people and communities most susceptible to COVID-19. As a result, we know that elderly people, Black, indigenous, people of color and people with underlying conditions are more likely to lose their life after becoming infected with the coronavirus.

Despite physical isolation from most of the outside world, people who are incarcerated have not been spared from the wrath of the pandemic. The nature of correctional confinement makes social distancing impossible and access to sufficient personal hygiene and cleaning products limited. Although, state and local governments are able to use CARES Act funding to maintain sanitary conditions and implement social distancing in state prisons and county jails, there is little evidence to demonstrate this type of resource allocation has in fact occurred.

Fulton County attempted to use $23 million dollars in CARES Act funding to ostensibly create solitary confinement rooms, masked as COVID-19 isolation units. Activism by organizations like the Black Futurists Group were able to shut down efforts to expand Fulton County Jail and instead push for funding that promoted community wellbeing. To date, the GDC has reported 1,847 and 720 positive coronavirus cases for incarcerated individuals and staff members, respectively. Of those cases, 41 individuals serving sentences and one staff member have lost their lives. While these numbers are troubling, the lack of mass testing within GDC facilities is leading to an under counting of cases.

To add to the dynamics at hand, the GDC has reported 11 prison murders since the agency’s internal pandemic restrictions began on March 12. Tensions within facilities are said to be running high amid the restrictions and mistreatment of those within facilities. Advocates and family members of individuals who are incarcerated are hearing reports of inhumane conditions, including unsanitary facilities and inadequate access to basic nutrition. The situation within GDC facilities is dangerous for both incarcerated people and staff members. When coupled with an ongoing global pandemic, it is incumbent on the state to reexamine the situation and assess the risks being inflicted upon those inside.

Aging Prison Population and Prevalence of Chronic Conditions

Georgia’s historic enforcement of “tough on crime” policies yielded harsher sentences that have unsurprisingly led to a prison population that is older on average today than it has been in the past. Although the general population may define an older adult as someone age 65 or older, GDC typically defines older incarcerated adults as those age 50 or older. Researchers believe that incarcerated adults who are 50 years old present a similar physical state to non-incarcerated adults who are 65 years old.

The 50-year-old threshold to define older adults within confinement is primarily due to lower life expectancy, associated with stressors from prison life such as anxiety due to a change in environment, isolation and exclusion from family and society and the threat of victimization, which disproportionately affects older incarcerated people. Additionally, older incarcerated adults are more likely to have chronic and mental health conditions often identified as the collateral consequences of poverty, drug and alcohol addiction and the lack of access to preventive health care. At the end of 2019, the GDC reported that 38 percent of its population suffered from chronic conditions such as diabetes, congestive heart failure or asthma, and that 20 percent of the GDC population had a mental health diagnosis. The agency granted 57,013 medical consults and filled 1.2 million prescriptions in 2019 alone.

The average age of people who are incarcerated in Georgia has risen since the start of tough on crime policies, from 29 in 1979 to 39 in 2020. Today, there are 10,469 people in GDC custody who are age 50 or older, representing roughly 20 percent of the total GDC population. In addition to the health care risks faced by older incarcerated adults, the state incurs exponentially higher costs in their medical care. A 2013 GDC study found that on average, yearly medical costs for people age 65 or older amount to $8,500 compared to $950 for those who are younger. As the population of older incarcerated people continues to grow, so too will state spending on health care for the GDC.

The Legal Right to Health Care

The Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution is supposed to protect individuals from “cruel and unusual punishment.” Under this amendment, people who are incarcerated in the custody of state, federal or local correctional systems are entitled to health care. The U.S. Supreme Court in Estelle v. Gamble (1976) found that people who are incarcerated have a right to be free of “deliberate indifference to their serious health care needs,” and that deliberate indifference is a violation of a person’s Eighth Amendment rights.

Litigation has given rise to three basic health care rights, which are recognized by the GDC:

- The right to access health care services;

- The right to a professional medical judgment; and

- The right to care that is ordered by a health care professional.

Amid a global pandemic, the ability to access health care is imperative. The GDC has published several press releases in which they identify the measures they are taking to slow the spread of COVID-19 within GDC facilities. Every day, however, the GDC reports a higher case count and death toll within facilities, which further indicates an inadequacy in their safety precautions. The Georgia National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Southern Center for Human Rights have both called for increased transparency by the GDC of coronavirus case data and for improved conditions within facilities. In 2018 alone, the state paid out $3 million dollars to settle prison medical negligence lawsuits.

Historical medical negligence by the GDC reveals that the health care needs of people who are incarcerated are not, in fact, being taken seriously. A prison sentence during a global pandemic can mean a death sentence, and there is no justice in dying behind bars due to the indifference of those who have the power to decide to provide health care or not. The GDC has a responsibility to care for those in their custody, and the current coronavirus data demonstrates that responsibility is being ignored.

Recommendations

- The GDC should mirror state-level coronavirus case and fatality metrics and make data available that is disaggregated by race/ethnicity, age and gender.

- The GDC must ensure that COVID-19 testing is widely available to those who are incarcerated within their facilities and to correctional staff, provide face masks and ensure they are worn by everyone, and provide adequate and timely medical care.

- Lawmakers should continue to evaluate the impact of 2012 justice reform measures to ensure that expected outcomes are being met and sustained long-term. They should also consider further reforms to drive down the GDC population.

- Lawmakers should hold the GDC accountable for reported inhumane conditions within facilities to address concerns around nutrition, mistreatment and access to hygiene products. Lawmakers should also investigate allegations of retaliation by the GDC against those in their custody for speaking out about these conditions.

[1] While the term ‘criminal justice system’ is most commonly used to refer to the system of law enforcement in this country, the system has historically demonstrated a failure to achieve true justice. As such, GBPI will intentionally use ‘criminal legal system’ to refer to the current system moving forward. (Nixon, V., & Atkinson, D. [2020]). Introduction. In What We Know: Solutions from Our Experiences in the Justice System. The New Press.)

[2] The GDC population data used in this blog reflects those reported in the GDC’s monthly “Profile of All Inmates” reports and includes all individuals housed in the following facilities: State Prisons, County Correctional Institutions, Transitional Centers, Private Prisons, County Jails, and State Hospitals. Notably, excluded from the monthly Profile of All Inmates report are individuals in Detention Centers (1,456) and RSAT Centers (1,651), which the GDC reports in its Annual Statistical Reports entitled “Average Daily Population By Facility.”