Introduction – Why An Economic Opportunity Agenda for Georgia Women?

The economic status of women in Georgia is a key factor in the overall health and future of the state’s economy. Women represent a majority of Georgia’s adult population[1] and nearly half of the workforce.[2] In more than half of all Georgia households with children, women are primary or co-breadwinners.[3]

Despite their importance, women face a host of barriers keeping them and Georgia’s economy, from reaching their full potential. Women working full-time in Georgia earn, on average, 70 cents for every dollar white men earn.[4] The gender wage gap is even wider once part-time workers are taken into account.

Georgia stands to gain a lot by removing these barriers to equal earnings for working women and their families. The state’s economy could add a staggering $14.4 billion if all working women in Georgia earned the same amount of money as men living in similar population areas, of the same age, education level and working the same number of hours.[5] Even more money could be added to Georgia’s economy if women who are now not working got more support, including child care and health care, which can allow them to rejoin the workforce or work more hours.

Increasing earnings for Georgia women can also provide a powerful boost to working families themselves. Lower earnings for Georgia women make it more likely they and their families will live in poverty, which carries a host of negative implications for the future of the state’s workforce and overall well-being. Poverty for Georgia’s working women could fall by nearly half if women earned the same amount of money as men in comparable circumstances.[6] Lower pay also makes it harder for women to afford health care which is essential to their heath and overall well-being.

Policy interventions are collectively one of the most important tools for helping to close the gender earnings gap and boost Georgia’s economy. The pay gap is driven by several distinct causes and as a result requires diverse solutions. Pay disparities exist largely because women are more likely to work in industries that pay a low wage, have higher caregiving burdens than men and more often work part-time jobs as a result of their caregiving responsibilities. This report is the first in a series designed to spotlight four policy actions Georgia can take to begin to address some of these underlying causes and unleash the economic potential of Georgia women:

- Closing Georgia’s coverage gap by expanding Medicaid eligibility can extend health insurance coverage to more than 155,000 women in the state, helping to keep them healthy enough to fully participate in the workforce

- Making child care affordable and accessible for more families can make it easier for women to balance their disproportionate caregiving responsibilities, allowing them to enter or stay in the workforce and work more hours

- Enacting the Georgia Work Credit, a state Earned Income Tax Credit can provide a modest wage enhancement that encourages low-wage women to stay employed and work more hours

- Raising the state minimum wage to $10.10 per hour can increase the incomes of nearly one in four Georgia women working in low-wage jobs and funnel hundreds of millions of dollars back into the economy

This list of policies to address the gender earnings gap in Georgia is just a starting point. They build on policy proposals already under discussion in the state and can provide a firm foundation for future leaders to build upon. Future iterations of this report will explore policies from around the nation Georgia can import to address the earnings gap.

Women and Girls: A Critical Resource for Georgia

A growing, diverse, educated population of women and girls is an important asset for Georgia to achieve a brighter future. The population of women and girls in Georgia has more than doubled since 1970, reaching 5.2 million in 2014. Women and girls continue to be a critical part of the state, representing 51 percent of the state’s population. Georgia women have become a more significant part of its workforce, growing from 40 percent of workers in 1970 to nearly 48 percent in 2015.[7] Georgia’s economic competitiveness is inseparable from the ability of women and girls to succeed.

The backbone of Georgia’s economy is its workforce living primarily in the state’s metro areas. The geographic location of the state’s women and girls tracks this reality. About 56 percent of women and girls live in metro Atlanta while another 28 percent live in other metro areas. [8]

As millennials and young people become ever more relevant to the future of the workforce, the importance of Georgia’s women is as well. About 53 percent of Georgia’s women and girls are younger than 40.

Women are also well represented among the young educated millennials Georgia and other states are trying to attract. Nationally, 37.5 percent of millennial women ages 25 to 34 hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. In contrast, only 29.5 percent of millennial men have similar educational attainment.[9] Georgia can attract educated millennial women by demonstrating equality of opportunity in the state.

Georgia has experienced some success in attracting women and their families from other states and countries. About 33 percent of Georgia women and girls were born in another state and nearly 10 percent are immigrants to the United States.

Migration helps Georgia build a diverse population and workforce. Fifty-four percent of women and girls in Georgia are white, 32 percent are African-American, 9 percent are Hispanic, 4 percent are Asian and 0.2 percent are Native American. The remainder of Georgia’s women identify with either two or more races or some other race. Georgia’s female population is projected to continue to grow even more diverse in coming years as the state nears a day when it has no racial majority.

Georgia Women and Girls at a Glance

- Nearly half of Georgia’s workforce consists of women

- Most of Georgia’s women and girls are younger than 40 and live in metropolitan areas

- Nearly half of women and girls are of color

Women Vital to Georgia Workforce, Families and Future

Earnings for Georgia women are increasingly important to the vitality of Georgia families. In 1970, 45 percent of married Georgia women worked outside the home.[10] Now, 59 percent of married Georgia women are in the labor force.[11] Participation in the workforce for Georgia single mothers is picking up as well. The share of single mothers who work increased to 83 percent from around 66 percent since 1970, while the share of Georgia families with children headed by single women more than doubled since 1970.[12] Today, 29 percent of families with children are headed by single women.[13]

Women Now Represent Nearly Half of Georgia’s Workforce

Share of Georgia Labor Force by Gender, 1970

Georgia Labor Force by Gender, 2015

In nearly 52 percent of all Georgia families with children women are breadwinners who are either the sole providers or earn at least 40 percent of family earnings. This share puts Georgia slightly above the national average.

Nearly half of all families with children across the United States have breadwinner mothers. [14] The growth of breadwinner mothers can be traced to increasing numbers of women entering the labor force over the past four decades through both choice and necessity. Increased numbers of single mothers and higher job losses suffered by men since the Great Recession started in 2007 are also contributing factors.[15]

Since most Georgia families with children are headed by breadwinner mothers while women earn less than men in comparable circumstances on average, there are a host of implications for Georgia’s future. Research shows that a child’s future income, likelihood of attending college and chance of becoming a teenage parent are all tied to parental income.[16] Academic achievement gaps between poor and low-income children and their higher-income peers also arise early in life and widen as children age.[17] As Georgia women’s pay becomes increasingly more important to family incomes, limited earning potential for women is likely to hinder outcomes for children and consequently Georgia’s future.

52%

Share of Georgia families with children where women are breadwinners

Breadwinners are women who are either the sole providers or earn at least 40 percent of family earnings. Source: Institute for Women’s Policy Research Analysis of American Community Survey Microdata (Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Version 6.0).

Women and Georgia’s Earnings Gap

Addressing barriers to equal earnings for Georgia women has tremendous economic potential for the state. If working women in Georgia earned the same amount of money as men living in similar population areas, of the same age, education level and working the same number of hours a staggering $14.4 billion can be added to Georgia’s economy each year. Even more money can be added to Georgia’s economy if women who are not working now got more supports, including child care and health care, to allow them to rejoin the workforce or work more hours.

Equal earnings for Georgia women can also have a positive effect on Georgia’s poverty rate, which ranks as the seventh highest in the nation. The poverty rate for Georgia’s working women can fall by nearly half if women earn the same amount of money as comparable men.

To achieve the $14 billion economic potential of equal pay for Georgia women, a number of factors must be addressed. Women in the state fare worse as measured by earnings and poverty despite their education and abilities. Women’s lower post-recession earnings are affected by both individual choices and systemic barriers. It is important to examine the gender earnings gap in Georgia and some of its causes including field of study, occupational choice, domestic responsibilities and hours worked. The gender earnings gap carries implications for poverty and health care coverage.

The Earnings Gap for Georgia Women

Georgia women earn less than men on average. Women in the state who work full-time year-round earn an average of $36,000 per year compared to $44,000 for men. The median earnings for Georgia women working full-time, year round were only 70 percent of the average earnings for white men in the state in 2014.[18]

Larger Earnings Gap for Georgia Women of Color

For Georgia women of color, the gender earnings gap is even more pronounced than for white women. The larger gap is due to many factors including differences in occupations, lower educational levels, as well as bias and discrimination in the workplace. Women of color are more likely to work in the low-wage service sector partly because lower education levels for some women of color – particularly Black and Hispanic women – create barriers for them in attempting to enter higher-paying professional fields.

Still, although education improves the earning potential of all women, black and Hispanic women tend to be paid less than white and Asian women even when they share the same educational backgrounds. This indicates either implicit or explicit bias may affect take home pay.[19]

Gender Earnings Gap is Largest for Women of Color

Ratio of Georgia Women’s Earnings to White Men’s Earnings, by Race/Ethnicity

Lower Earnings for Georgia Women Not Due to Lower Educational Achievement

Lower earnings for Georgia women are generally not due to lower levels of education. Georgia women are more likely than men to earn a bachelor’s degree or higher, or have some college education or an associate’s degree. In 2014, about 60 percent of Georgia women had attended at least some college compared to 55 percent of Georgia men.

Georgia Women More Likely to Have Higher Education Than Men

Educational attainment of Georgians age 25 and older by gender

Higher educational attainment among Georgia women tracks national trends. Women in the U.S. surpassed men in earning bachelor’s degrees in 1981 and that held true every year since.[20]

Although women are generally better educated than men, choices about college majors do play a part in the gender earnings gap. Men are more likely to major in higher-paying fields like engineering and computer science, while women are more likely to major in lower-paying fields like education and the social sciences. The choice of college major can x lower potential earnings for an entire career since benefits and pay raises are typically an outgrowth of initial wages.[21]

Women’s choice of college major also seems to be influenced by the degree of flexibility in the jobs associated with the concentration.[22] Women handle a disproportionate share of unpaid household labor and that future obligation might factor into their major and career choices.

Educational Attainment for Georgia Women Varies by Race

Educational gains made by Georgia women are not evenly realized across racial groups. Asian and white women are more likely than Native American, black and Hispanic women to hold an associate degree or higher. Black and Hispanic students secure college degrees at a lower rate due in part to their tendency to attend less competitive, more crowded colleges with higher dropout rates stemming from underfunding.[23] Black and Hispanic students are also more likely to have lower incomes, which makes tuition costs a barrier to college completion.[24]

Asian and White Women Most Likely to Have Higher Education

Share aged 25 and older with associate’s degree or higher, by gender and race/ethnicity

Occupations: Georgia Women More Likely to Work in Fields with Low Pay

Georgia women are more likely to pursue and attain college degrees but they still earn less than men at each education level. This is due in part to women and men choosing different occupations.

More than half of this country’s gender earnings gap in the U.S. is due to the concentration of men and women in different occupations or sectors of the economy.[25] This is evident in Georgia as more than half of women are employed in two of Georgia’s lowest paying fields compared to nearly a third of men.

Similar Levels of Education Yield Lower Pay for Women

Median earnings in the past 12 months by sex by educational attainment for the population 25 years and older

Nearly one in three Georgia women is employed in a sales or office occupation where the typical annual earnings are $27,138. Sales and office occupations include administrative assistants, retail workers, cashiers and customer service representatives. Less than one-fifth of Georgia men are in those fields.

Nearly 20 percent of women are employed in service occupations where the typical annual earnings are $16,906. Service jobs include home health aides, cooks, waitresses and building maintenance workers. Just 15 percent of men are in those jobs.

| Occupation | Women | Men |

| Sales and office | 32% | 18% |

| Service | 19% | 15% |

| Education, legal, community service, arts and media | 15% | 7% |

| Management, business and financial | 14% | 16% |

| Blue-collar jobs (e.g., construction, transportation) | 8% | 36% |

| Healthcare practitioners | 8% | 2% |

| Computer, engineering and science | 3% | 7% |

Source: Author’s calculation based on U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2014 1-year estimates

Jobs in retail, food service and home health care often require the majority of work to be performed outside of of the typical workday that falls between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. Workers in the service sector are often subjected to unpredictable just-in-time scheduling, making it difficult for women to arrange transportation, child care and classes to increase education. This unpredictable schedule also makes it difficult for women to budget for their needs each month and then earn enough money to cover them.[26]

The concentration of women in low-paying sectors of the economy makes women more likely to work in low-wage jobs. Working women in Georgia are more than twice as likely as their male counterparts to work at a job paying $10.10 or less per hour.[27]

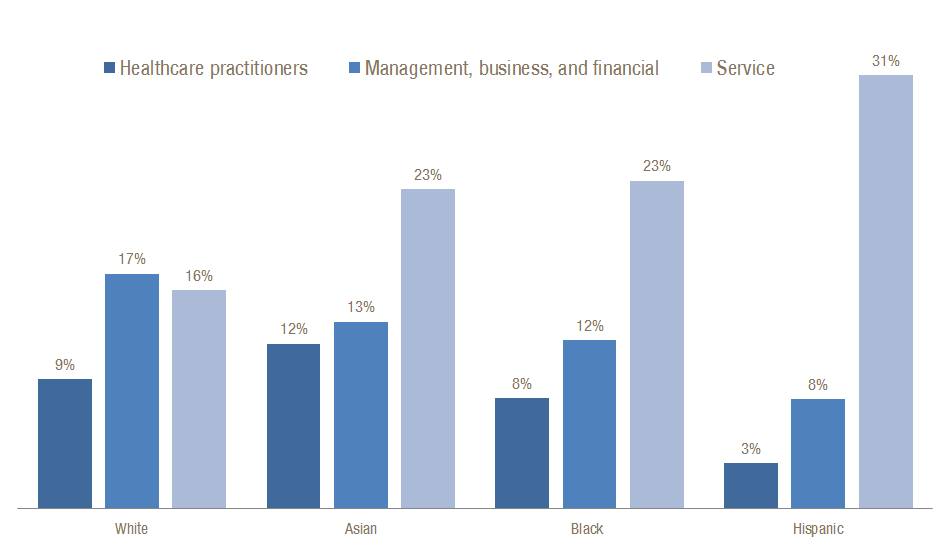

Women of Color More Likely to Work in Low-Wage Sectors

Women of color in Georgia are more likely to work in the low-wage service sector than white women. This contributes to the wider gap between their earnings the typical white man. Black and Hispanic women are also much less likely than white women to work in fields with better pay such as management, business and health care. Lower education levels for black and Hispanic women create barriers for them in attempting to enter higher-paying professional fields.[28]

Women of Color Less Likely to Work in Higher-Paying Sectors

Share of employed women age 18 and older by Occupation and Race/Ethnicity

There is no single greater policy lever than equal pay to increase women’s earnings and grow the economy

– Institute for Women’s Policy Research

Caregiving: Disproportionate Caregiving Responsibility Limits Women’s Ability to Work, Earnings

The gender pay gap is also a function of women’s greater caregiving responsibility for older people, children and people with disabilities. This disproportionate responsibility to do unpaid work often interferes with women’s participation in the workforce.[29]

Women are far more likely than men in Georgia to work part-time to make room for family care obligations.[30] Part-time work means lower earnings and also that women are less likely to get employer-provided health insurance, paid leave, or pension plans.[31]

Georgia Women More Likely to Work Part-Time

Share of employed workers who are part-time

Home Responsibilities Pull More Women From Workforce

Percent of total population 25 to 54 years of age citing “Home Responsibilities” as reason for not participating in the labor force

The responsibility for unpaid home care can also force some women to exit the workforce entirely for a while. Women across the country ages 25 to 54 who are not in the workforce cite home responsibilities as their leading reason for not working. Women are nearly 12 times more likely than men to cite this as the reason they are not working. [32]

The gap between the labor force participation rates of mothers and fathers of children under six is a clear illustration of the toll that unpaid care work can take. Georgia is one of 20 states with the widest gap between mothers’ and fathers’ labor force participation rates.[33]

The gender gap in labor force participation for parents plays a significant role in the overall gap between all Georgia men and women in labor force participation rates. Among Georgians ages 25 to 54, about 87 percent of men participated in the labor force in 2015 while nearly 72 percent of women did. In 37 other states women 25 to 54 participated in the labor force at a higher rate.[34]

Georgia’s economy has much to gain from increased labor force participation by women. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates boosting women’s labor force participation by 2 percentage points, narrowing the gap between the number of women and men who work full-time, and moving women to more productive industries like manufacturing and business services can boost the state’s economic output by $63 billion. Increasing women’s labor force participation and narrowing the gender gap for full-time work accounts for 71 percent of this growth.[35]

Georgia Mothers Less Likely to Work than Fathers

Labor force participation rates for women and men with children under six

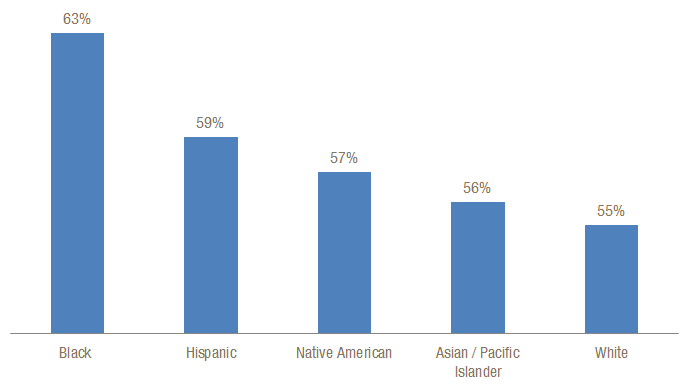

Black Women Have Highest Labor Force Participation Rates

Black women in Georgia have the highest labor force participation rates among all women. Black women are historically more likely than white women to participate in the labor force and to hold jobs in agriculture and manufacturing. This racial gap in workforce participation could have been the result of a greater stigma against white married women working in physically demanding jobs than black women. Society was more likely to accept married black women working in physically demanding jobs while it viewed married white women doing similar tasks negatively.

Significant increases in the growth of white women’s labor force participation coincided with the growth of jobs that were less physically demanding. The racial difference in women’s workforce participation rate persisted partly because daughters are more likely to work outside the home if their mothers did.[36]

Differences between the labor force participation rates for women of color and white women also might stem from white mothers leaving the workforce at higher rates. Opting out is more prevalent among white mothers than Asian, black and Hispanic mothers according to one study by the U.S. Census. White mothers are more likely to be in an occupation where they can negotiate a reduced schedule. Higher family incomes for white and Asian mothers may also give them the flexibility to work fewer hours.[37]

Black Women, Women of Color Have Higher Labor Force Participation

Labor force participation rates for women by race

Poverty: Lower Earnings Lead to Higher Poverty for Georgia Women

Georgia women make less money than men, leaving them more likely to live in poverty. More than 17 percent of Georgia women 18 and older live below the poverty line, or $19,073 in annual income for a family of three with two children. That compares to only 13 percent of Georgia men.

Georgia’s large share of women living in poverty is partly a reflection of high poverty in the state. Georgia is the seventh poorest state in the nation. More than 1.8 million people, or 18 percent of all residents – live in poverty. The state ranks about the same for poverty among women. Georgia is home to the eighth largest share of women living in poverty.

This high level of poverty carries dire implications for Georgia’s future. Poverty weakens our competitiveness. A vibrant economy depends on a strong middle class with robust purchasing power. Poverty also increases health costs as people who struggle with it are more likely to be uninsured, put off preventive care due to cost and make avoidable hospital visits. Poverty also lowers our long-term competitiveness as a state as affected children and young adults are less likely to attend college. That leaves them less prepared for high-skilled jobs of the future.

Closing the gender earnings gap can help mitigate poverty among Georgia women and strengthen the state overall. If working women in Georgia were paid the same as comparable men, the poverty rate among all working women would be cut nearly in half.

Closing Gender Earnings Gap Would Cut Poverty for Working Georgia Women Nearly in Half

Equalizing earnings for women and men can also significantly reduce poverty among single working mothers, which is a demographic important to the future of Georgia. The share of Georgia families with children headed by single women more than doubled since 1970 and continues to grow. The poverty rate among working single mothers would be cut by nearly 44 percent if working women in Georgia were paid the same as comparable men.

The gender earnings gap’s cumulative effect is also evident in poverty rates of Georgia’s older population. Nearly 13 percent of Georgia women ages 65 and older live in poverty compared to 7 percent of men the same age. Georgia women must survive on lower incomes for longer periods because they typically live longer than men do. Women’s lower earnings during their working years also make it more difficult for them to set aside money for retirement. Women are also more likely to work in jobs without retirement plans, in part because they are often in lower-paying and part-time jobs.[38]

8th Worst

Georgia’s ranking among states for women living in poverty

Source: Institute for Women’s Policy Research Analysis of American Community Survey Microdata (Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Version 6.0).

Women are the Majority of Older Georgians…

Georgians 65 and older, by gender

…And the Majority of Poor Older Georgians

Adults 65 and older in poverty, by gender

Black and Hispanic Women Have Highest Poverty Rates

Black and Hispanic women are the least likely to secure a college degree and the most likely to work in low-wage sectors when compared to white women in Georgia. Partly due to those two factors, they have the largest earnings gap when compared to white men in the state. Thus it is no surprise that women of color are more likely to live in poverty in Georgia when compared to white women. Black and Hispanic women in Georgia are about twice as likely to live in poverty as white women. One in four Black women in the state and more than one in five Native American women lives in poverty.

Black and Hispanic Women More Likely to Live in Poverty

Poverty Rates for Women by Race

Health: Georgia Women Less Likely to Have Health Insurance Compared to Other States

Lower pay and higher poverty for Georgia women also carries implications for their health. Adults living in poverty are more likely than counterparts with higher incomes to report being in poor health and adults with lower incomes also are at higher risk of heart disease, diabetes, stroke and other chronic disorders than wealthier Americans.[39]

Poor health can prevent women from fully participating in the workforce as it makes it more likely they will experience absenteeism or working while ill or injured. Workers with health-related disabilities are less likely to be able to perform basic tasks at work like lifting small objects, kneeling or standing for two hours.

The health of Georgia women with lower incomes is also directly affected by their inability to obtain health insurance. Women as a whole are more likely than men to have health insurance, but uninsured Georgia women with low incomes are more likely to go without health care because of cost. So they’re less likely to have a regular source of care and receive preventive care at lower rates than those with health insurance.[40]

Georgia Women with Health Insurance More Likely to Get Preventive Services

| Indicator | Low-Income Women Without Health Insurance | Low-Income Women with Insurance |

| In the last 12 months, have needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost | 66.3% | 26.2% |

| Have a personal doctor or health care provider | 50.6% | 83.0% |

| Had a “regular checkup” in the last two years | 67.3% | 90.8% |

| Had a mammogram in the past two years (aged 40+)* | 45.6% | 79.5% |

| Had a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy (aged 50+)* | 40.8% | 64.8% |

| Had a Pap test in the past three years (18+)* | 65.6% | 82.5% |

| Ever tested for HIV | 58.2% | 50.5% |

| In the last 12 months, have had either a seasonal flu shot or a seasonal flu vaccine that was sprayed through the nose | 16.3% | 35.1% |

*These questions are based on BRFSS data from 2012. Source: National Women’s Law Center analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Data (BRFSS), 2014

Only 79.6 percent of Georgia women ages 18 to 64 are insured compared to 85.4 percent of women in the United States.[41] That makes Georgia among the five worst states for women’s health care coverage.

Georgia 1 of 5 States Where Women Are Least Likely to Have Health Insurance

Share of Adults 18-64 Years Old with Health Insurance

The low coverage rates are due in part to the state’s refusal to expand Medicaid coverage to people with incomes at or below 138 percent of the poverty line, or about $27,800 for a family of three. More Georgia women ages 18 to 64 depend on Medicaid for their insurance coverage than men. Federal law allows states to expand Medicaid under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

Georgia Women More Likely to Be Covered by Medicaid

Share with Medicaid or means-tested public coverage 18 to 64 years of age

Georgia Women of Color Less Likely to Be Insured

Georgia women of color are less likely to carry health insurance than their white counterparts, partly because they are disproportionately represented in low-wage jobs which are less likely to offer employer-based health coverage. Even when employers offer health coverage, women of color typically earn lower incomes making it tougher for them to afford health insurance.

Nationally, women of color are more likely to depend on Medicaid for coverage than white women. This presents a particular challenge in states like Georgia did not expand Medicaid income eligibility. Women who are recent immigrants are doubly challenged by Medicaid eligibility restrictions. Immigrant women do not qualify for Medicaid for at least five years after entering the United States legally. Undocumented women are barred from both Medicaid eligibility and from purchasing insurance through state-based exchanges set up through the federal health care law.[42]

Women of Color Less Likely to Be Insured

Percent of Women with Health Insurance by Race/Ethnicity and State, 2013

Unleash the economic potential of women in Georgia

Capitalizing on the Earning Potential of Georgia’s Women

Georgia can implement several policy options to help unleash the economic earning potential of its women. Eliminating the earnings gap can add more than $14 billion to Georgia’s economy and cut the poverty rate for women in half. Four specific and viable policy opportunities for achieving that goal are outlined below. These four build on policy proposals under discussion in Georgia. Future editions of this report will identify additional potential solutions from around the nation to address the earnings gap.

Close Georgia’s Coverage Gap by Expanding Medicaid

Expanding eligibility for Medicaid could close Georgia’s coverage gap and extend health insurance to more than 300,000 uninsured adults in Georgia with incomes at or near the poverty line, including more than 155,000 women.[43] Federal funding through the Affordable Care Act can pay at least 90 percent of the costs to cover newly-eligible patients.

Uninsured Georgians with incomes below the poverty level are particularly affected by Georgia’s refusal to expand Medicaid eligibility. These are people stuck in a coverage gap as their income is too high to qualify under Georgia’s strict Medicaid eligibility rules, yet make too little to qualify for financial assistance under the federal health insurance marketplace.

Closing Georgia’s coverage gap is good for the state’s workforce and economic competitiveness. The majority of people who fall in Georgia’s coverage gap are in working families. Many of them work in Georgia’s most important industries, including construction, transportation, education and retail. Georgia ranks among the bottom five states for women’s health insurance coverage. That increases their chances of poor health. So many potential workers suffering poor health undercuts the strength of Georgia’s workforce and the state’s competitiveness.

Increasing health coverage for Georgia women is a smart investment. Women are more likely than men to rely on Medicaid and will be able to participate in the workforce longer and more consistently if they get needed care to be healthy. Georgia women are the breadwinners in more than half of Georgia households with children. So health insurance offers them financial protection by significantly reducing the strain of medical bills.

Closing the coverage gap is also a great deal for Georgia’s economy. Medicaid expansion-related revenue can exceed expansion-specific state spending by $148 million over the four years from 2016 to 2019, according to a 2013 analysis by Dr. William Custer of Georgia State University. Each $1 invested by the state from 2016 to 2024 can generate more than $12 in new federal funding for the state’s healthcare system and generate a $24 return for the state’s economy as a whole. This new economic activity is expected to create more than 56,000 jobs.

For more information on Georgia’s Medicaid program and the benefits of closing Georgia’s coverage gap through its expansion, go to gpbi.org to see Understanding Medicaid in Georgia and the Opportunity to Improve It.

155,000

Georgia women in health care coverage gap

Expand Child Care Assistance

Improved child care assistance can help close the gender earnings gap by helping women balance disproportionate caregiving responsibility for children. Women are far more likely than men in Georgia to work part-time because of family care obligations. The responsibility for unpaid care work at home also forces some women to exit the workforce entirely for a while. Women across the country ages 25 to 54 who are not in the workforce cite home responsibilities as their leading reason for not working. They are nearly 12 times more likely than men to cite this as the reason they are not working.[44]

The high cost of child care can be a severe financial impediment for women’s full workforce participation. The average annual cost of center-based child care for an infant in Georgia is $7,644. The average cost is $3,692 for a school-aged child.[45] These costs can easily consume 40 percent of a low-income family’s budget.

Helping parents with the high costs of child care strengthens today’s workforce in two ways. It helps Georgia’s low-income working parents become better workers and helps unemployed parents join the ranks of the employed. Research shows that parents who receive help paying for child care are more likely to work. They are also more likely to:

- Work with fewer child care-related disruptions, such as missed days, schedule changes and lost overtime hours

- Work more hours and stay employed longer

- Earn more income to support the family

- Stay employed at higher rates

Georgia’s child care assistance program can be strengthened to serve more low-income families in need. Georgia assists with the care of nearly 50,000 children weekly.[46] That is a fraction of the 682,000 children under 13 years old in low-income working families who likely need quality child care.[47]

For more information on the benefits of child care assistance, go to gbpi.org to see Child Care Assistance: Georgia’s Opportunity to Bolster Working Families, Economy. And for the child care funding challenges, see Help Needed to Meet Georgia’s Laudable Child Care Goals.

Child Care Can Equal Nearly 40% of a Low-Income Family Budget

Georgia Child Care Assistance Helps Only a Fraction of Those In Need

Enact the Georgia Work Credit, a state Earned Income Tax Credit

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) cuts federal taxes and provides a modest wage enhancement for low-wage workers – predominately women. The credit is available only to people who work and it grows as wages rise. That encourages people to stay employed and work more hours, rather than rely on public assistance to make ends meet. Nearly 1.1 million Georgia households , or 28 percent of all Georgia income tax filers received the federal EITC in 2013.

The federal credit is refundable, which means if a family’s credit exceeds their income tax liability, they receive the spillover as a refund. For a detailed explanation of how the credit works go to gbpi.org to see A Bottom-Up Tax Cut to Build Georgia’s Middle Class.

Twenty six states and the District of Columbia build on the federal EITC’s success with their own state-level versions of the tax credit. State EITCs piggyback on the federal version by providing a limited credit against state and local taxes up to a value each state sets. The largest value goes to families making from about $10,000 to $23,000 a year. Families making up to about $38,500 to $52,500 can still benefit, depending on number of children.[48]

State EITCs are typically claimed as a percentage of the federal credit’s value, ranging from a low of 3.5 percent in Louisiana to a high of 40 percent in Washington, D.C. If Georgia were to enact a refundable EITC set at a 10 percent state match, a family with a $3,000 federal credit also receives a $300 state credit. A Georgia EITC this size would put an estimated $270 million annually into the pockets of about 1.1 million Georgia households, 70 percent of whom include working mothers.

Georgia’s working mothers and their children stand to gain the most from a state EITC. It can provide a hand up for 900,000 women in Georgia paid low wages, over half of whom are the sole or primary earner for their family.[49] An estimated 770,000 working mothers can benefit, along with 410,000 working fathers.[50] Working mothers are likelier to receive the tax credit because they typically are more likely to raise children alone and work in low-wage occupations. Children in families with working parents who receive the tax credits perform better in school, are more likely to attend college and tend to earn more as adults.

The EITC boosts work hours, especially among single mothers

– Research Review, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

A Georgia Work Credit can help women keep working despite low wages. This is especially important given that one of the reasons for the gender earnings gap is that fewer women than men work in Georgia. The tax credit lets low- and moderate-income working mothers keep more of what they earn to help pay for things that keep them employed, such as child care and transportation.

For women with very low wages, the credit increases with each dollar earned. That encourages them to work more hours. Studies show the EITC boosts work effort especially among single mothers. That additional experience in the workforce can lead to higher pay and better opportunities. The tax credit phases out after recipients reach a modest income level.

Research suggests that the EITC’s boost to work hours and earnings of working women also boosts their Social Security retirement benefits, which helps reduce poverty in old age. This is especially important given that women are more likely to live in poverty than men.[51]

40%

Share of Georgia’s working women who would benefit from a state Earned Income Tax Credit

Raise the state minimum wage

Georgia is one of only seven states with a state-level minimum wage below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. The state’s $5.15 per hour minimum wage applies to a small subset of workers exempt from federal requirements, such as people working for very small businesses. Most Georgia workers are subject to the $7.25 an hour federal wage floor. Raising Georgia’s minimum wage to $10.10, phased in over a period of three years, can help close the gender earnings gap, increase incomes of women workers and likely funnel millions of dollars back into the economy.

Increasing the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour can close about 5 percent of gender wage gap, according to the President’s Council of Economic Advisers.[52] States that set their minimum wages higher than federal minimum wage have a smaller gender earnings gaps.[53]

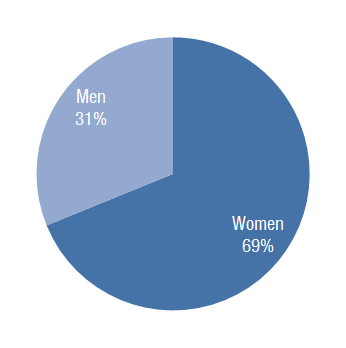

In Georgia, about six in 10 minimum wage workers are women.[54] A low minimum wage that loses value each year is more likely to hurt working women than working men.

The minimum wage is not automatically adjusted for inflation or price increases. So each year the minimum wage is not increased, low-wage workers lose valuable purchasing power. Today the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour is worth $2.29 less than in 1968, as measured in 2014 dollars. The real purchasing value will only continue to diminish if it is not raised or at least linked to inflation.[55]

A $10.10 minimum wage can raise wages for nearly a half-million women in Georgia. An estimated 56 percent of the Georgia workers who stand to benefit from a minimum wage increase are women, even though women make up less than half of Georgia’s workforce. In fact, nearly one in four women in Georgia would see wages increase as a result of a $10.10 minimum wage.

Raising the minimum wage can put $342 million more into the hands of women who are more likely to spend it immediately. Women who benefit from a minimum wage increase would see their cumulative wages rise by more than $340 million. Women who make less than $10.10 today would gain an extra $700 in annual income, on average, with a $10.10 minimum wage. The $342 million cumulative wage increase can be expected to funnel back into Georgia’s economy as women across the state use their boosted incomes to support their families and pay for basic necessities.

Women are two-thirds of tipped workers nationally and suffer disproportionately from a low tipped subminimum wage.[56] The federal government in 1996 established a subminimum wage for tipped workers at $2.13 an hour, which is less than 30 percent of the federal minimum wage. Georgia is one of 17 states yet to set a higher subminimum wage for tipped workers.[57]

An employer is expected to make up the difference if a tipped worker can makes less than $7.25 per hour in wages and tips. This rule it is not consistently enforced. In the 2010 to 2012 compliance sweep of 9,000 restaurants by the U.S. Department of Labor alone, investigators found 1,170 violations of the tipped minimum wage rule that resulted in payments of nearly $5.5 million in back wages.[58]

Wages for tipped employees are generally lower than for other workers. In states like Georgia, where tipped workers are only paid $2.13 an hour, the poverty rate for women workers in tipped occupations is 22 percent. This compares to a 15 percent poverty rate for workers in tipped occupations in states where there is no subminimum wage.[59]

The tipped subminimum wage also puts women at greater risk of sexual harassment because it creates a culture in which workers must endear themselves to customers to make a living. It also allows a few bad employers to withhold cash unless certain requests are met. Workers in states with a subminimum wage, including men and non-tipped workers, report higher rates of sexual harassment. Women who live in states with a $2.13 an hour subminimum wage are twice as likely to be sexually harassed as women in states with no subminimum wage.[60]

Georgia should eliminate the subminimum wage. Raising the full minimum wage while keeping the tipped subminimum wage aggravates today’s enforcement problems. Eliminating the lower minimum wage for tipped workers helps mitigate the gender earnings gap as well. The gender pay gap is smaller in states that require employers to pay tipped workers the regular minimum wage than states with a $2.13 tipped minimum wage. [61]

For more reasons why Georgia should increase its minimum wage, read Better Pay for Honest Work.

Conclusion

Georgia leaves behind more than $14.4 billion in potential additional household income for its residents because women are not earning the same amount of money as men in the state. This missing money is critical to Georgia’s future since women are responsible for bringing in at least 40 percent of family earnings in more than half of the state’s families with children. Leveling the pay gap can also cut poverty for Georgia women by as much as half, providing a powerful boost to both working women and their families.

Georgia can remove barriers that stand between women and equal earnings and at the same time realize a resulting economic boon. Women are likelier to work in economic sectors that pay a low wage. They carry higher caregiving responsibilities than men. And they tend to work fewer hours due to caregiving responsibilities.

Georgia can make concrete policy decisions to knock down these barriers, close the gender earnings gap and boost the state’s economy in the bargain. This report spotlights four initial steps within Georgia’s grasp to unleash the economic potential of Georgia women:

- Close Georgia’s coverage gap through the expansion of Medicaid

- Make child care more affordable and accessible

- Enact the Georgia Work Credit, a state Earned Income Tax Credit

- Raise the state minimum wage to $10.10 per hour

Acknowledgments & Endnotes

This report is made possible by the generous support of the Working Poor Families Project, a national initiative funded by the Annie E Casey, Ford, Joyce and W.K. Kellogg foundations.

This report is made possible by the generous support of the Working Poor Families Project, a national initiative funded by the Annie E Casey, Ford, Joyce and W.K. Kellogg foundations.

The Georgia Budget and Policy Institute would also like to thank the Institute for Women’s Policy Research for the data provided in the Status of Women in the South report published in February 2016. This analysis is enriched by the Georgia-specific data and insights on economic parity and opportunity included in that report.

END NOTES

[1] Author’s calculation based on US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2014 1-Year Estimates Table B01001.

[2] Economic Policy Institute analysis of 2015 Current Population Survey data.

[3] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 79.

[4] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 53.

[5] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Pages 36-37.

[6] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 109.

[7] Author’s calculation based on US Census Bureau, “Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1974,” p.852; Economic Policy Institute analysis of 2015 Current Population Survey data.

[8] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2014 1-Year Estimates.

[9] US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2014 1-Year Estimates.

[10] Author’s calculation based on labor force statistics from US Census Bureau, 1970 Census of the Population, Characteristics of the Population: Georgia, Issued March 1973.

[11] Author’s calculation based on US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2014 1-Year Estimates.

[12] Author’s calculation based on labor force statistics from US Census Bureau, 1970 Census of the Population, Characteristics of the Population: Georgia, Issued March 1973; US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2014 1-Year Estimates.

[13] Author’s calculation based on US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2014 1-Year Estimates.

[14] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 79.

[15] Sarah Jane Glynn, “The New Breadwinners: 2010 Update, Rates of Women Supporting their Families Economically Increased Since 2007,” Center for American Progress, April 16, 2012.

[16] Alison Griswold, “Here’s the Startling Degree to Which Your Parents Determine Your Success,” Business Insider, January 24, 2014.

[17] Julie Vogtman and Karen Schulman, “Set Up to Fail: When Low-Wage Work Jeopardizes Parents’ and Children’s Success,” National Women’s Law Center, 2016.

[18] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 53.

[19] “The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap,” American Association of University Women, Spring 2016.

[20] Rose, Deondra. 2015. “Regulating Opportunity: Title IX and the Birth of Gender-Conscious Higher Education Policy.” Journal of Policy History 27 p. 157-183.

[21] “The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap,” American Association of University Women, Spring 2016.

[22] Matthew Wiswall and Basit Zafar, “Preferences for the Workplace, Investment in Human Capital, and Gender,” Association for Education, Finance, and Policy, January 2016.

[23] Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, “Separate and Unequal: How Higher Education Reinforces the Intergenerational Reproduction of White Racial Privilege,” Georgetown Public Policy Institute Center on Education and the Workforce, July 2013.

[24] Institute for Research on Higher Education. (2016). College Affordability Diagnosis: National Report. Philadelphia, PA: Institute for Research on Higher Education, Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania. http://www2.gse.upenn.edu/irhe/affordability-diagnosis.

[25] Ariane Hegewisch, Marc Bendick, Barbara Gault, Heidi Hartmann, “Pathways to Equity: Narrowing the Wage Gap by Improving Women’s Access to Good Middle-Skill Jobs,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, March 2016, Page 6.

[26] Julie Vogtman and Karen Schulman, “Set Up to Fail: When Low-Wage Work Jeopardizes Parents’ and Children’s Success,” National Women’s Law Center, 2016.

[27] Interactive Map: Women and Men in the Low-Wage Workforce, National Women’s Law Center. Available at http://nwlc.org/resources/interactive-map-women-and-men-low-wage-workforce, Accessed June 20, 2016.

[28] Milia Fisher, “Women of Color and the Gender Wage Gap” Center for American Progress, April 14, 2015

[29] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 35.

[30] Geographic Profile of Employment and Unemployment, 2014 – Table 23. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. <http://www.bls.gov/opub/gp/pdf/gp14_23.pdf>.

[31] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 70-71.

[32] Steven F. Hipple, “People who are not in the labor force: why aren’t they working?,” Beyond the Numbers: Employment & Unemployment, vol. 4, no. 15 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2015), http://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-4/people-who-are-not-in-the-labor-force-why-arent-they-working.htm (accessed July 7, 2016).

[33] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 87.

[34]Author’s calculations based on “States: Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population by sex, race, Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and detailed age, 2015 annual averages,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor.

[35] “The Power of Parity: Advancing Women’s Equality in the United States,” McKinsey Global Institute, April 2016. Raw number increase in GDP calculated by author using U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (2015).

[36] Leah Platt Boustan and William J. Collins, “The Origins and Persistence of Black-White Differences in Women’s Labor Force Participation” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 19040, May 2013.

[37] Liana Christin Landivar, “Who Opts Out? Labor Force Participation among Asian, Black, Hispanic and White Mothers in 20 Occupations,” Industry and Occupation Statistics Branch, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, U.S. Census Bureau, May 2012.

[38] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 61.

[39] Steven H. Woolf, Laudan Aaron, Lisa Dubay, Sarah M. Simon, Emily Zimmerman, Kim X. Luk, “How Are Income and Wealth Linked to Health and Longevity,” Urban Institute and Center on Society and Health, April 2015.

[40] Stephanie Glover, “States Must Close the Gap: Low-Income Women Need Health Insurance,” National Women’s Law Center, October 2014.

[41] Julie Anderson, Elyse Shaw, Chandra Childers, Jessica Milli, and Asha DuMonthier, “The Status of Women in the South,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, February 2016, Page 98.

[42] Alina Salganicoff, Usha Ranji, Adara Beamesderfer, and Nisha Kurani, “Women and Health Care in the Early Years of the Affordable Care Act: Key Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, May 2014.

[43] Rachel Garfield and Anthony Damico, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid – An Update,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, January 21, 2016.

[44] Steven F. Hipple, “People who are not in the labor force: why aren’t they working?,” Beyond the Numbers: Employment & Unemployment, vol. 4, no. 15, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2015, http://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-4/people-who-are-not-in-the-labor-force-why-arent-they-working.htm (accessed July 7, 2016).

[45] “Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2015 Report”, Child Care Aware of America.

[46] Average weekly number of children served in federal fiscal year 2016, Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning, February 2016.

[47] Working Poor Families Project, Analysis of American Community Survey, 2013 (Washington, D.C: Population Reference Bureau).

[48] Wesley Tharpe, “A Bottom-Up Tax Cut for Georgia’s Middle Class: The Case for a State Earned Income Tax Credit,” Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, August 2015.

[49] Estimate provided by the nonpartisan, nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, D.C.

[50] “Who Would Benefit from a Georgia EITC?,” http://georgiaworkcredit.org/who-would-benefit/ (accessed July 7, 2016).

[51] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon Debot, “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 1, 2015.

[52] “The Impact of Raising the Minimum Wage on Women: And the Importance of Ensuring a Robust Tipped Minimum Wage”, The White House, March 2014

[53] Julie Vogtman and Katherine Gallagher Robbins, “Higher State Minimum Wages Promote Fair Pay for Women,” National Women’s Law Center, May 2015.

[54] “Women and the Minimum Wage, State by State” National Women’s Law Center, August 2015.

[55] David Cooper, “Raising the Minimum Wage by $12 by 2020 Would Lift Wages for 35 Million American Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, July 14, 2015.

[56] Katherine Gallagher Robbins, Julie Vogtman, & Joan Entmacher, “States with Equal Minimum Wages for Tipped Workers Have Smaller Wage Gaps for Women Overall and Lower Poverty Rates for Tipped Workers,” National Women’s Law Center, May 2015.

[57] “Minimum Wages for Tipped Employees,” US Department of Labor.

[58] Sylvia Allegretto and David Cooper, “Twenty-Three Years and Still Waiting for Change: Why It’s Time to Give Tipped Workers the Regular Minimum Wage,” Economic Policy Institute, July 10, 2014.

[59] Katherine Gallagher Robbins, Julie Vogtman, & Joan Entmacher, “States with Equal Minimum Wages for Tipped Workers Have Smaller Wage Gaps for Women Overall and Lower Poverty Rates for Tipped Workers,” National Women’s Law Center, May 2015.

[60] “The Glass Floor: Sexual Harassment in the Restaurant Industry,” The Restaurant Opportunities Centers United and Forward Together, October 7, 2014.

[61] Katherine Gallagher Robbins, Julie Vogtman, & Joan Entmacher, “States with Equal Minimum Wages for Tipped Workers Have Smaller Wage Gaps for Women Overall and Lower Poverty Rates for Tipped Workers,” National Women’s Law Center, May 2015.