Note on Nov. 11, 2021: In 2021, Georgia was approved to expand postpartum Medicaid to six months. Federal lawmakers are debating requiring states to extend the program to one year after giving birth.

Georgia lawmakers are considering a measure to allow mothers who receive Medicaid to keep their coverage for six months after their delivery. Medicaid plays an important role in maternal health in the state because it pays for half of all births each year.

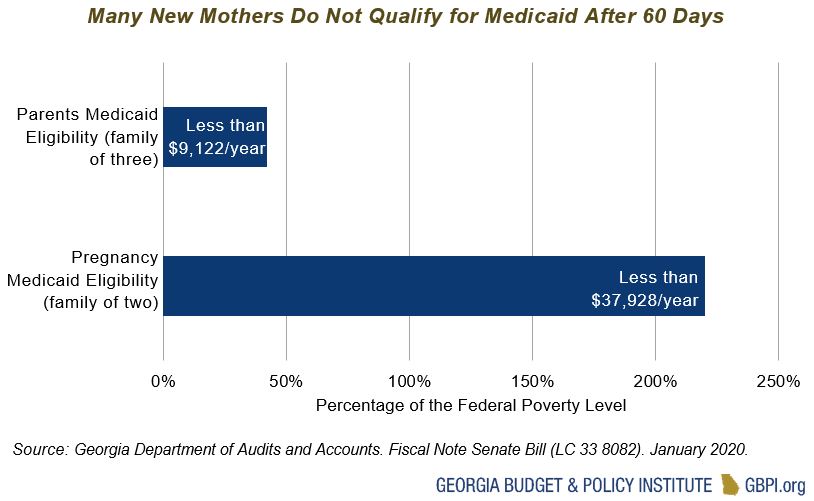

Currently, pregnant women making less than 220 percent of the federal poverty line (less than $37,928 a year for a family of two) can receive Medicaid until up to 60 days after the birth or miscarriage. Once the 60 days end, they can reapply for Medicaid, but they would have to meet a different eligibility criteria, called Parents Medicaid Eligibility, that requires an income below 42 percent of the poverty line. This means that a family of three would need to earn less than $9,122 a year to continue their Medicaid coverage.

Because of the more restrictive Medicaid eligibility for parents, many new mothers no longer qualify for Medicaid. Due to this and other barriers, 76 percent of Georgia’s new mothers who make less than 220 percent of the poverty line made too much money to qualify for Medicaid after the 60 days[1]

They may be able to enroll in the state’s Planning for Healthy Babies Medicaid waiver, which covers family planning services for women with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line, but it does not cover other postpartum health needs such as chronic disease management and mental health treatment. Some of these mothers do not earn enough to get premium subsidies in the Affordable Care Act marketplace and/or may face other challenges to finding a new health insurance plan, leaving them without comprehensive coverage during part of the critical postpartum period. Twenty-two percent of Georgians who gave birth in the last year reported not having health coverage.[2]

Preventing Maternal Deaths in Georgia

Comprehensive postpartum care is an important component to preventing maternal mortality. Georgia ranks no. 49 among states for the rate of maternal mortality, defined as deaths related to pregnancy that occurred during or within one year of the pregnancy or birth. [3]

Georgia established a Maternal Mortality Review Committee in 2014 to identify maternal deaths and their causes. The committee found that between 2012 and 2014, 101 mothers died from pregnancy-related causes (such as cardiomyopathy, hemorrhage, preeclampsia and other conditions) and about 60 percent of the deaths were preventable.

The committee also found significant evidence of the maternal mortality crisis Black women are facing in Georgia. The maternal mortality rates for Black women in Georgia were three to four times higher than for white women. The committee, as well as House Study Committee on Maternal Mortality and House Study Committee on Infant and Toddler Social and Emotional Health, included the postpartum Medicaid extension in their recommendations to help address the maternal mortality crisis.

Currently no states have implemented the postpartum Medicaid extension, but several states are pursuing the option through Medicaid 1115 waivers. Applying for a waiver is the only way to enact the policy and get federal Medicaid matching funds, unless proposed federal legislation passes to make it a state option.

Postpartum Medicaid Extension Is Cost-Effective

Fiscal notes published late last year and early this year show a 10-month extension of Medicaid for pregnant women would cost the state $44 million in the first year and $70 million in the second year. About 5,096 women are expected to become eligible for the extension each month, for a total estimate of about 61,000 new mothers receiving extended coverage each year.

Although the state currently faces steep budget cuts, the extension would be relatively cost-effective; moreover, there are additional considerations that could offset this cost. For example, state agencies like the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities could save money because of more opportunities to bill Medicaid for services. The agency added $1.05 million of state funds to the 2020 budget to screen and treat maternal depression in rural areas. The governor’s proposed amended 2020 budget replaces these state funds with federal Maternal and Child Health block grant funding, but billing Medicaid would be a more sustainable funding source to keep up these efforts.

The state could also reduce the costs by taking advantage of the federal money available to the state to expand Medicaid and cover more pregnant women after the 60 days. Medicaid expansion would cover some of the pregnant women who lose their coverage and make less than 138 percent of the poverty line, or $29,000 a year for a family of three. Seventy-eight percent of uninsured new mothers in Georgia making below the pregnancy Medicaid limit of 220 percent of the federal poverty line would qualify for full Medicaid expansion.[4] Expanding Medicaid would allow the state to receive a 90 percent federal match compared to the 67 percent federal match used in the fiscal notes, lowering the total cost to the state for the postpartum extension.

Furthermore, a recent study in Women’s Health Issues showed that Medicaid expansion is associated with lower rates of maternal mortality by about 7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared to states that did not expand Medicaid.[5] Black women had the largest drop in maternal mortality in states that expanded Medicaid, showing the success of expanded coverage in helping end the maternal mortality crisis for Black women. Georgia submitted a federal waiver in December of 2019 that would partially expand Medicaid and is awaiting approval. But the plan is only expected to cover 50,000 of the estimated 400,000 who are eligible—compared to about 500,000 people covered under full Medicaid expansion—and it would be funded at the lower 67 percent match rate.

Extending postpartum Medicaid coverage can also bring economic benefits, such as preventing productivity losses related to untreated mental illnesses or substance use disorders and expensive emergency room visits and hospitalizations for chronic illness. Maternal depression and anxiety can occur up to a year after pregnancy ends; it is the most common complication of pregnancy. About 12.5 percent of Georgia women who recently gave birth reported postpartum depression.[6] An analysis from Mathematica showed that untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders have an average economic cost of $5,300 per year.[7] The postpartum Medicaid extension could help more mothers get treatment and avoid these unnecessary costs.

Some Chronic Illnesses or Mental Health and Substance Abuse Conditions Require More Than Six Months of Care

Extending postpartum Medicaid coverage for six months would be an excellent first step, but to best improve outcomes, Georgia should look at extending coverage for one year. The Georgia Maternal Mortality Review Committee found that about 27 percent of maternal deaths between 2012 and 2014 occurred between 43 days to 1 year after birth. In 2014, the committee determined 67 percent of the pregnancy-related deaths occurring between 6 months and one year could have been prevented.[8] Extending coverage can play a role in some of the preventable deaths that occur after Medicaid coverage ends. A longer coverage period is also important for addressing the rising rates of maternal morbidity, health challenges for women after giving birth such as chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease and substance abuse that could lead to death if left untreated.

Extending coverage from two months after birth to six months is a start, but women in substance abuse treatment, treatment for postpartum depression or diabetes management programs could still face gaps in their care. Women can receive screening for maternal depression through their child’s Medicaid plan, but without coverage they often do not have an option to get treated. For substance abuse treatment, the coverage disruption can have a greater effect in the later postpartum months. An August 2018 study found that “opioid overdose deaths decline during pregnancy and peak in the seven to 12 months postpartum.” [9]

Children are automatically enrolled in Medicaid for one year after they are born, but research from Health Affairs shows that some babies experience coverage interruptions.[10] One reason is related to the mismatch in the length of coverage for mothers and babies. Services for newborns must be billed through their mother’s Medicaid identification number. When the mother loses coverage, it can cause a disruption in coverage for the baby if a new number is not generated in time. Bringing coverage for the mother and child in alignment to a full year and allowing more time for mothers to transition during longer-term treatments is the best way to maximize the benefits of the policy.

Given the critical role of Medicaid in maternal health in Georgia and the flexibility for states to innovate and make changes to Medicaid policy, Georgia can take a big step in ending the maternal mortality crisis and reducing maternal morbidity by extending postpartum Medicaid coverage to one year.

[1] GBPI analysis of American Community Survey 5-year estimates (2014-2018)

[2] GBPI analysis of American Community Survey 5-year estimates (2014-2018)

[3] America’s Health Rankings. 2019. Maternal mortality in Georgia. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/health-of-women-and-children/measure/maternal_mortality_a/state/GA

[4] GBPI analysis of American Community Survey 5-year estimates (2014-2018)

[5] Eliason, E.L. (2020, February 25). Adoption of Medicaid expansion is associated with lower maternal mortality. Women’s Health Issues. https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(20)30005-0/fulltext

[6] America’s Health Rankings. 2019. Postpartum depression in Georgia. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/health-of-women-and-children/measure/postpartum_depression/state/GA

[7] Luca, D.L., Garlow, N., Staatz, C., Margiotta, C., & Zivin, K. (2019, April). Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica. https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-findings/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

[8] Georgia Department of Public Health. (2019, March). Maternal Mortality Review Committee report, 2014. https://dph.georgia.gov/document/publication/maternal-mortality-2014-case-review/download

[9] Schiff, DM, et al. (2018). Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstetrics & Gynecology. Retrieved Marcy 5, 2020 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29995730

[10] Johnson, K., Rosenbaum, S., & Handley, M. (2020, January 9). The next steps to advance maternal and child health In Medicaid: Filling gaps in postpartum coverage and newborn enrollment. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191230.967912/full/