Key Takeaways:

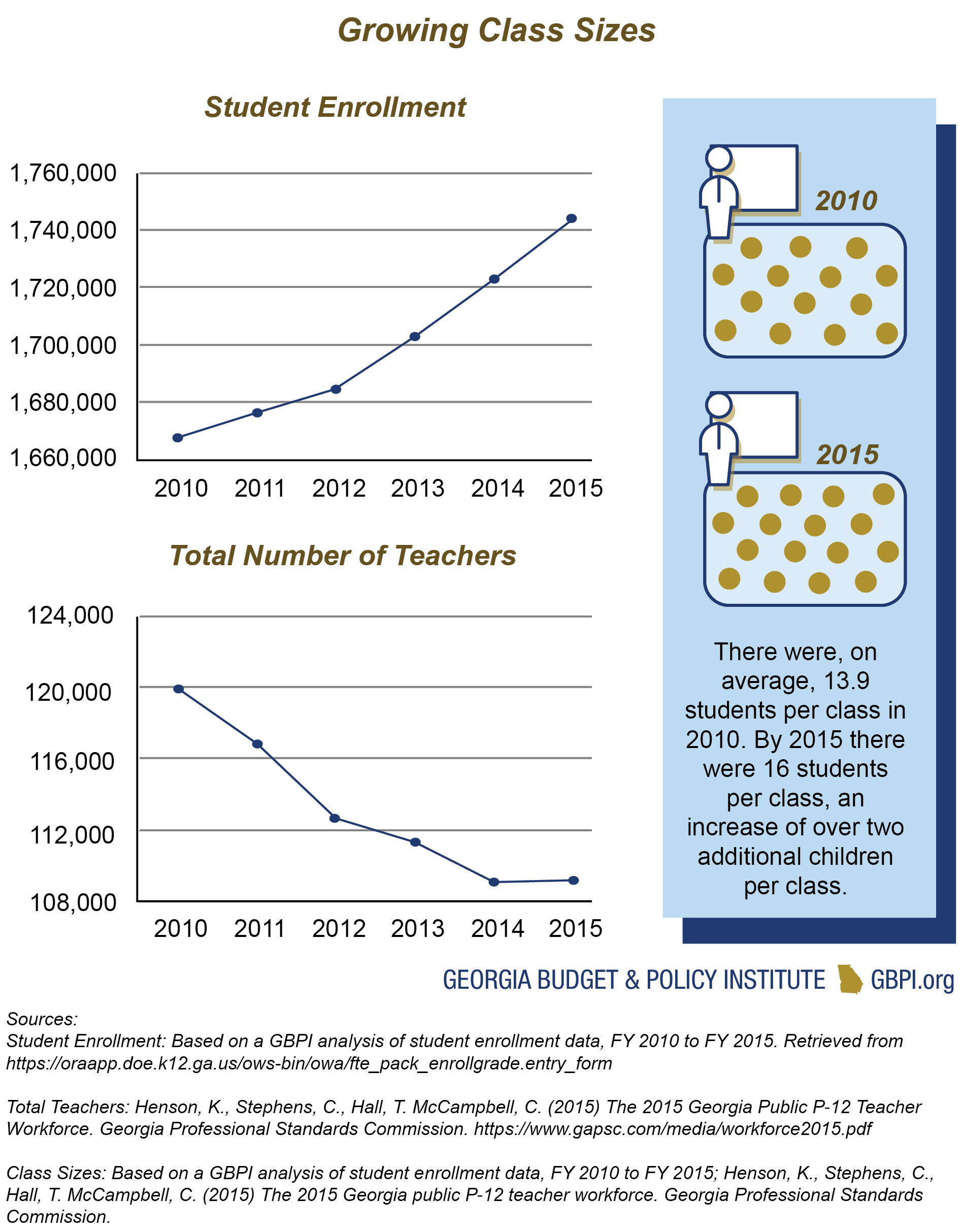

- Due to COVID-19, Georgia revenues are lagging. State leaders must either raise new revenues or make steep cuts to the budget, but budget cuts could devastate K-12 education for years to come. Austerity in the wake of the Great Recession led to increased class sizes, the end of enrichment programs such as art and music and furlough days for teachers. Students are still feeling the effects.

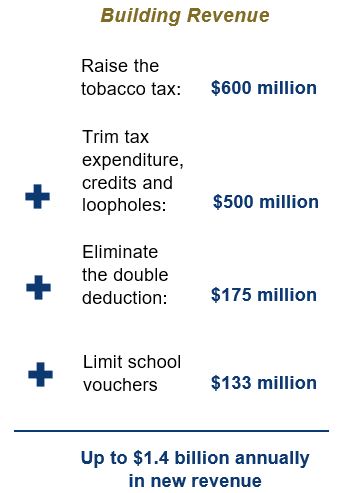

- There are simple options to raise up to $1.4 billion revenues in Georgia, such as raising the tobacco tax to the national average, trimming tax expenditures and loopholes and eliminating the state’s double deduction. The state can also limit the school voucher programs, which have sent $881 million to private schools in the last 12 years.

- If the state is forced to make cuts to K-12 education, those resulting budget cuts must be (a) temporary, (b) equitable and (c) contextual. For example, the majority-Black, rural school districts in Georgia’s Black Belt already experience fewer educational opportunities than the rest of the state of Georgia. These same districts are often in regions most affected by COVID-19. School districts such as these should be held harmless from any budget cuts in order to avoid further damaging the already-hurting communities.

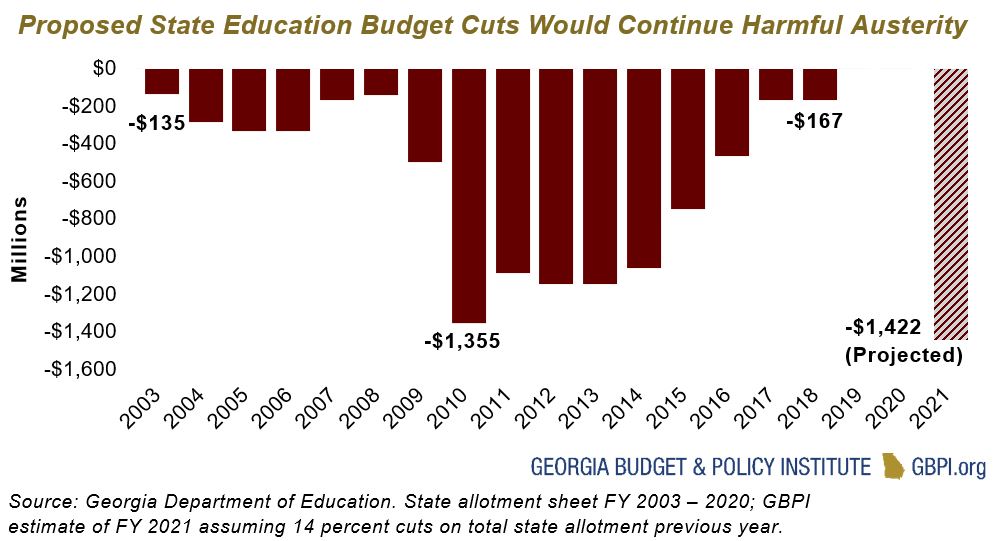

As local school districts prepare to make severe budget cuts due to the impact of the novel coronavirus, lawmakers have an opportunity to protect the education of Georgia’s 1.8 million school children through sensible revenue raisers. The directive to reduce state agency budgets by 14 percent has the potential to cut $1.5 billion from the total Department of Education budget, $1.42 billion of which goes directly to local schools.[1] If state lawmakers plan to cut budgets in the same way that was employed in the years following the Great Recession, the fallout will accelerate a massive economic downturn and cause harm to a generation of public school students. The chart below shows what is at stake.

Georgia students who began kindergarten in FY 2010 when billion-dollar austerity began will only be in 11th grade in the FY 2021 school year. Any future budget cuts will mean that this cohort of children only experienced two school years without deep financial losses. During the last 20 years, Georgia lawmakers cut billions of dollars from public education. These cuts took three basic forms: austerity cuts, formula changes and shifting burden of payment away from the state. First, austerity cuts were temporary budget cuts ranging from $135 million to $1.4 billion annually from the Quality Basic Education Act (QBE) funding calculation.[2] Second, in 2012 lawmakers made a structural change to the formula that dictated grants paid to low property-wealth school districts, called equalization grants, in order to lower the amount of money required by the state. After years of underfunding the grant, the formula change reduced equalization earnings from $830 million in FY 2013 to $474 million in FY 2014.[3]

Finally, at the same time that the state was sending billions less to schools through austerity and changes to equalization, Georgia stopped contributing to health insurance for bus drivers, cafeteria workers, maintenance workers and other non-teaching staff.[4] When stakeholders mention Georgia lawmakers’ success in “fully funding education,” that is only a reference to ending austerity cuts in FY 2019. Lowering equalization and ending payments for school staff’s health insurance have left Georgia’s schools with billions less in funding and saddled with additional costs.

This first section of this report acts as a warning: what waits for the state if lawmakers attempt to follow the same playbook used in the years following the Great Recession. The report also offers commonsense solutions to the projected budget shortfalls for schools. Finally, if state leaders are forced to make budget cuts to public education, there are guiding principles for consideration to guarantee that state funding reductions are not paid for on the backs of children for years to come, especially in Black and Brown communities that have traditionally been underserved by the state.

Recalling the Mistakes of the Past: Results of Underfunding in the Great Recession

By 2014 in Georgia Schools:

A Way Forward: Responsible Revenue Raising

What follows is a menu of options that could be used to build the revenue base in a fair and inclusive way. Raise the tobacco tax: $600 million

What follows is a menu of options that could be used to build the revenue base in a fair and inclusive way. Raise the tobacco tax: $600 million

Georgia currently has the nation’s second-lowest tobacco tax, levying a fee of just 37 cents per pack of cigarettes. The national average is currently $1.81 a pack.[5] By raising the fee to the national average and taxing vaping products the equivalent amount, the state could gain the dual benefit of $600 million per year in additional revenue in the short term while disincentivizing smoking in the long run.[6]

Trim tax expenditures, credits and loopholes: $500 million

Georgia’s film tax credit is unique in that, if a studio cannot make use of a credit, they are allowed to sell (or transfer) it to anyone who owes Georgia taxes. The end result is that entities that might have no connection to the state’s film industry can avoid paying taxes meant for essential state services.[7] Eliminating these and other loopholes could result in an additional $500 million annually. GBPI has compiled a detailed explainer of the changes necessary to the state’s tax credits in a published menu of revenue options.[8]

Eliminate the double deduction: $175 million

Some Georgia taxpayers can write off their state income tax payments when calculating owed state income taxes. This quirk in Georgia’s tax law, called the double deduction, is only applicable to tax filers that make an average of $240,000 yearly and is unique nationwide: 46 other states do not allow the practice.[9] The end result has no clear economic benefit, yet the state forfeits $130 million to $220 million annually.[10]

Limit school vouchers: up to $133 million

State lawmakers created and bolstered two voucher programs that have sent $881 million to private schools in the last 12 years, even while public schools endured austerity cuts of $7.8 billion over that same time. In FY 2021, Georgia is projected to spend $133 million on these programs with zero evidence of success.[11] Lowering the funding provided to these vouchers would shore up the state coffers while recognizing the need to invest in the state’s public school system.

Building Revenue: up to $1.4 billion annually

Making these investments in Georgia’s children would help the state weather the current storm and set Georgians up for years to reap the benefits through increased state services, including education, made possible by strong leadership.

CARES Act Funding is a Band-Aid, Not a Cure

The federal government passed legislation in April (the CARES Act) that provides education funding to support schools as they are dealing with the effects of the pandemic. This $411 million will be used to offset the increased costs of remote instruction, school meal service, physical and mental health services and many other areas that arose due to the novel coronavirus. Due to the increased costs and the fact that this funding is temporary, the CARES Act cannot be counted on to fill the upcoming shortfalls in Georgia’s public education budgets.

Mitigate Harm: Equitable, Short-term Cuts

If the federal government does not provide additional relief for struggling state budgets, lawmakers may be left considering significant cuts to public education. If this is the reality, then resulting budget cuts must be (a) temporary, (b) equitable and (c) contextual. What follows is a rationale for three budget-cutting concepts with a potential policy solution to achieve each goal.

Temporary.

Lawmakers must reject structural changes to the way Georgia schools are funded. Any budget cuts should resemble the austerity cuts of FY 2003 to FY 2018, except with a deliberate eye towards filling the gap in funding as soon as financially able. By keeping cuts temporary, stakeholders can ensure that children are not paying the costs of the coronavirus years after the pandemic has been contained.

Policy recommendation:

Cuts should be explicitly accounted for on the state funding allocation sheets and, if continuing for more than one fiscal year, should include a cumulative amount for reference and accountability.

Equitable.

School districts in Georgia have unequal funding due to the state’s reliance on local property taxes as a large portion of the public education budget (see the following chart). Since the state acts as an equalizing agent through grants such as the equalization funding mentioned earlier, many districts with low property-wealth rely on state funding as a larger portion of their budget. Any state cuts that do not take into account property tax collection would disproportionately harm these districts.

Policy recommendation:

State budget writers could use property valuations to direct cuts in the same way the Local Five Mill Share is calculated.[12] In this way while all districts would receive less state money, those school districts that are unable to levy significant local taxes will be protected from the bulk of school budget cuts.

Contextual.

Any potential budget cuts are not happening in a vacuum. The novel coronavirus has caused an unparalleled halt in economic activity, and it has not been felt equally across the state. Nationwide the virus has been infecting Black communities at a higher rate.[13] In Georgia 49 percent of those with confirmed COVID-19 cases (omitting those cases marked “unknown” or “missing”) were Black Georgians, who make up only 32 percent of the state’s population.[14] At the same time, five of the ten worst-hit counties per capita in the United States are in rural, southwest Georgia.[15] These majority-Black, rural school districts in Georgia’s Black Belt already experience fewer educational opportunities than the rest of the state of Georgia, a practice that has a long history.[16] School districts such as these should be held harmless from any budget cuts in order to avoid further damaging the already-hurting communities.

Policy recommendation:

Georgia offers grants to rural school districts that do not enroll enough students to fund an adequate education, called sparsity grants. Many of the counties that have been hardest hit by the coronavirus have schools receiving sparsity grants. Policymakers should exempt school districts that receive sparsity grants and districts in counties with high confirmed cases (i.e. Dougherty County) from budget cuts.

Conclusion

The devastating policy decisions in the years after the Great Recession continue to underfund Georgia’s public education system. If there is anything to be gained from the last 12 years it is a blueprint for choices to avoid moving forward. State lawmakers can learn from the past to enact sound economic policy to support the state’s children.

Endnotes

[1] Salzer, J. (2020, May 1). Georgia agencies told to plan billions in spending cuts due to pandemic. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/state–regional-govt–politics/georgia-agencies-told-plan-billions-spending-cuts-due-pandemic/tLrAiX29jBWzIizTLzX8wN/

[2] Georgia Department of Education. State allotment sheet FY 2003 – 2020

[3] Johnson, C. D. (2012, February). Bill analysis: House Bill 824: House Bill 824 makes changes to Georgia’s K-12 Education Equalization Program. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://cdn.gbpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Bill-Analysis-HB-824.pdf; Georgia Department of Education, Quality Basic Education Earning Sheets FY 2013 and FY 2014.

[4] Suggs, C. (2014, September). The schoolhouse squeeze 2014: State cuts, lost property values still pinch school districts. Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. https://cdn.gbpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Schoolhouse-Squeeze-2014.pdf

[5] Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. (2019, January 14). State cigarette excise tax rates & rankings. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0097.pdf

[6] Harker, L. (2018, December 4). Increase the state tobacco tax for a healthier Georgia. Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2018/tobacco-tax-increase/

[7] Galloway, J. (2019, December 31). Analysis: Georgia’s film and TV incentives could become part of a 2020 budget battle. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/blog/politics/analysis-georgia-film-and-incentives-could-become-part-2020-budget-battle/WChRc5e9JFmxjkMv3nJi4N/

[8] Kanso, D. (2020, May 11). Georgia can’t afford another lost decade: Options to increase state revenues to close budget shortfalls. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2020/georgia-cant-afford-another-lost-decade-options-to-increase-state-revenues-to-close-budget-shortfalls/

[9] Kanso, D. (2020, May 11). Georgia can’t afford another lost decade: Options to increase state revenues to close budget shortfalls. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2020/georgia-cant-afford-another-lost-decade-options-to-increase-state-revenues-to-close-budget-shortfalls/

[10] Salzer, J. (2020, March 6). Ga House may go after ‘double deduction’ some get when they file income tax returns. Atlanta Journal Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/state–regional-govt–politics/georgia-house-may-after-double-deduction-some-georgians-get-when-they-file-income-tax-returns/DbQzkGzoZxg2fl7CRqfcyO/

[11] Owens, S. (2019, March 28). Bills set stage to divert hundreds of millions of dollars from public to private schools. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2019/millions-diverted-to-private-schools/

[12] Owens, S. (2019, May 23). How does Georgia fund schools? Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. (Video: 3-minute and 11-second mark, “5 Mills”). https://gbpi.org/2019/how-does-georgia-fund-schools/

[13] Brooks, R. A. (2020, April 24). African Americans struggle with disproportionate COVID death toll. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/04/coronavirus-disproportionately-impacts-african-americans/

[14] Georgia Department of Public Health. (2020). Georgia overall COVID-19 status. Retrieved 5/8/20 at 3:20pm from https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-daily-status-report; U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY RACE – Georgia – 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year estimates. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/GA

[15] Galofaro, C. (2020, May 6). ‘It’s gone haywire’: When COVID-19 arrived in rural America. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/b2a2add19ce7f4f75f42b29331034706

[16] Owens, S. (2019, October 10). Education in Georgia’s Black Belt: Policy solutions to help overcome a history of exclusion. Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2019/education-in-georgias-black-belt/