Key Takeaways:

- Expanded access to a driver’s card promotes family unity and enhances road safety.

- GBPI projects that approximately 165,000 Georgia immigrants could benefit from expanded access to driving privileges.

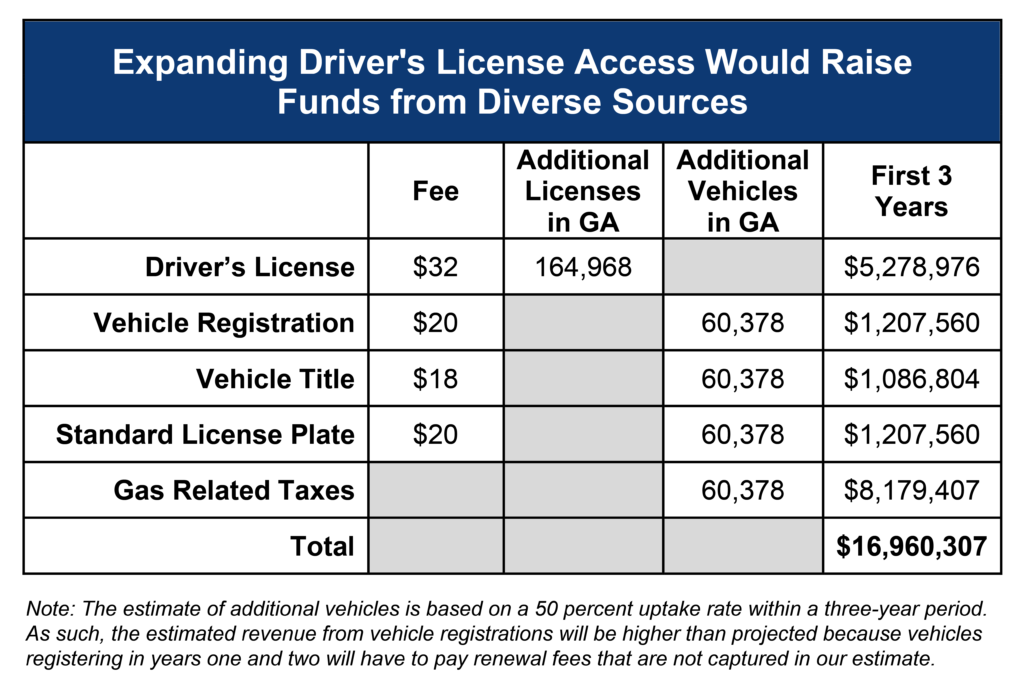

- During the first three years of implementation, the state could gain almost $17 million in revenue from driver’s card fees, motor fuel taxes, vehicle registration, vehicle title and standard license plate fees.

The value of a driver’s license is often taken for granted. But it is a tool that is frequently necessary to navigate everyday tasks like driving to work, picking up groceries and dropping kids off at school. It also helps provide identification when picking up prescription medication, opening a bank account or attending a doctor’s appointment. While seeming insignificant, a driver’s license facilitates many day-to-day activities that are essential to meeting basic needs.

Access to a driver’s license, however, is denied to Georgian immigrants lacking legal status. Following the enactment of the REAL ID Act of 2005, many states including Georgia amended their driver’s license laws, limiting driver’s license access to those who could provide proof of legal status. Prior to 2008, any Georgia resident regardless of legal status could acquire a driver’s license upon satisfying all other requirements. The enactment of SB 488 barred those without status from accessing a driver’s license.[1] Georgia law also criminalizes the act of driving without a license, thereby punishing immigrants for failing to have a driver’s license denied to them by the state.[2]

The Georgia General Assembly has an opportunity during the 2021 legislative session to roll back anti-immigrant driving restrictions in state law and afford Georgia immigrants’ access to a tool that would ease the daily challenges that come from lacking legal status. Expanding driving privileges to immigrants without legal status would also align the Peach State with the commonsense practices of 16 other states.[3],[4]

Expanding Access to Licenses Promotes Family Unity

Georgia law criminalizes the act of driving without a license and simultaneously prohibits Georgians without legal status from acquiring a driver’s license.[5],[6] This nonsensical practice forces undocumented Georgians to risk arrest on a daily basis just to go to work and conduct other essential activities to provide for their families. An individual caught driving without a license can be charged with a misdemeanor and subsequent violations can eventually lead to a felony record.[7] The criminalization of this minor traffic offense could impede an individual’s ability to adjust to legal status if immigration reform is passed in the future, a possibility which is now more likely given recent developments at the federal level.[8]

The risk undertaken is even greater for those living in or commuting through counties where local sheriffs have signed 287(g) agreement with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The 287(g) program deputizes state and local officials to perform the functions of federal immigration agents. Some local law enforcement offices also comply with voluntary, non-binding detainer requests from ICE that allow them to hold individuals at local county jails for 48 hours beyond the time they otherwise would have been released.[9] The voluntary agreements that the state and local law enforcement offices have with ICE lead to family separation and prolonged detention of many individuals whose initial contact with law enforcement stemmed from the mere lack of a driver’s license.

The Georgia Department of Corrections and six counties across the state including Floyd, Hall, Oconee, Polk and Whitfield counties have voluntarily opted into the 287(g) program.[10] Notably, Hall and Whitfield counties have high undocumented resident populations making local cooperation with ICE an even greater threat to families residing in these areas.[11] When ICE detains or deports undocumented parents, their children often get caught up in the state’s child welfare system.[12] Those children are then forced to endure psychological trauma and mental health issues resulting from familial separation and potential abuse in the child welfare system. Nationwide, ICE deported 27,080 parents of U.S. citizen children in 2017.[13]

The results of the 2021 sheriff’s races in Cobb and Gwinnett counties provide hope to immigrant residents as victors in both counties have affirmed their intent to end their agreements with ICE.[14] In fact, the Gwinnett County Sherriff terminated the county’s participation in the program on his first day in office, and the Cobb County Sherriff ended their relationship with ICE on Jan. 19, 2021.[15],[16] The state legislature can build on this momentum and similarly support immigrant communities across the state by allowing undocumented Georgians to access a driver’s license and rejecting anti-immigrant legislation during the 2021 legislative session.

Reforming Driver’s License Laws Yields Benefits Across Communities

Reforming eligibility requirements for Georgia driver’s licenses and driver cards would not only benefit undocumented Georgians but also assist members of other communities. By expanding the list of documents an applicant can present to establish identity and state residency, those who have difficulty accessing the limited list of accepted documents for a driver’s license will also benefit.

Returning Citizens

Individuals who were formerly incarcerated often face many barriers when reentering society following their release. On average, the Georgia Department of Corrections has released 17,700 people every year over the last five years.[17] A driver’s license or state ID is an essential tool that returning citizens need to secure employment, housing and reliable transportation. Returning citizens would benefit if the state expanded the list of eligible documents to obtain a driver’s license to include prison or parole discharge papers that identify the applicant’s name, date of birth and photograph. As such, this legislation would also assist returning citizens in more easily obtaining access to the tools they will need to restart their lives.

Domestic Abuse Survivors

In Georgia, 37.4 percent of women and 30.4 percent of men experience intimate partner physical violence, sexual violence or stalking at some point in their lives.[18] Survivors of intimate partner violence may struggle to find safe housing. In fact, in FY 2019 Georgia domestic violence shelters provided protection to 7,214 survivors but had to turn away over 4,000 people due to lack of shelter space.[19] Accessing important documents like birth certificates and passports can be particularly challenging for survivors of abuse who may be forced to leave their belongings behind. A more expansive list of accepted identity documents will enable survivors of intimate partner violence to access a driver’s card that they can use to secure safe housing and other essential resources.

Transgender Community

With an estimated population of 55,650 people, Georgia ranks No. 4 in the nation for the highest percentage of transgender residents.[20] In order for transgender individuals to change their gender marker on an ID or driver’s license, Georgia law requires the submission of a court order or a physician’s letter certifying the person’s gender change. These additional requirements can present a substantial obstacle for many people.

The creation of a driver’s card could allow transgender Georgians to obtain a state-issued form of identification with their accurate gender marker without having to jump through as many hoops.

Enhanced Road Safety

Allowing all immigrants, regardless of their legal status, to access a state-issued driver’s card would enhance road safety for all Georgians. Currently, undocumented Georgians are forced to drive without a license when necessary and as such are barred from taking the state’s road rules and driving exams. A report from the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety found that one in five fatal crashes involve an unlicensed or invalidly licensed diver and those drivers are 10 times more likely to leave the scene of a crash than validly licensed drivers.[21]

Aside from ensuring safer roads, access to a driver’s card for all immigrant drivers also facilitates the purchase of car insurance, a benefit for all Georgia drivers. When more Georgians are insured, all drivers could see a modest decrease in annual car insurance premiums. One recent study that analyzed a decade of state-level data found that the annual cost of insurance decreased by nearly $20 for drivers living in states that expanded driver’s license access to undocumented residents.[22]

Ultimately, when all Georgians are able to learn the rules of the road and have access to car insurance, everyone on the road is better off.

Promotes Pandemic-Era Safety Precautions

Public health officials have long urged the public to wear a mask, social distance and avoid enclosed spaces to reduce the spread of the coronavirus. The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us about the impact individual decisions can have on the well-being of the collective. Given the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on Black and immigrant communities, it is essential for lawmakers to consider advancing policies that protect these communities from further devastation.[23], [24] Undocumented Georgians are at an even higher risk of contracting the coronavirus since many rely on public transportation to get to and from work, the grocery store and other daily activities. The ability to access a driver’s card would allow more undocumented Georgians access to a safer transportation option and in turn could help curb community spread of the virus. Additionally, COVID-19 testing is often conducted through drive-in testing sites where individuals are asked for proof of identification. Thus, the lack of a driver’s license and vehicle present further barriers to basic health care access to those without legal status.

Modest Amount of Revenue Raised

If Georgia driver’s license laws were amended to expand access to Georgia residents without legal status, GBPI estimates that 164,968 undocumented Georgians would apply for a driver’s card within the first three years of implementation, which would, in turn, result in the purchase of 60,378 vehicles. As such, it is estimated that the state stands to raise over $5 million in revenue from driver’s cards by expanding access to Georgians without legal status over the first three years. The state can also expect to receive approximately $3 million in additional revenue from vehicle registration, vehicle title and standard license plate fees over the first three years of implementation. Finally, $8 million in additional revenue could be generated through the collection of motor fuel taxes within three years which can be used to build and maintain Georgia’s roads and bridges. (See ʺRevenue from the first three years of implementationʺ section below.)

Additional revenue will be generated through the Georgia Motor Vehicle Title-Ad-Valorem Tax (TAVT) which applies a 6.6 percent tax on the fair market value (FMV) of the vehicle being registered.[25] This tax is paid when vehicle ownership is transferred, or a new resident registers a vehicle in the state for the first time. Without a driver’s license, undocumented Georgians have not been able to register vehicles with the state, and, as such, the state has missed out on an additional revenue opportunity. Since the TAVT collected per individual will vary depending on the FMV of each vehicle, we are unable to accurately project the revenue the state stands to generate by reforming access to a driver’s card. But, in FY 2021, we projected the state could generate approximately $455 million in revenue from the TAVT.[26] Thus, by expanding access to a driver’s card to Georgians without status, the state can further bolster an important state revenue stream.

Revenue compared to additional costs

To keep up with an increase in the number of Georgia residents who will seek a driver’s card and register vehicles, the Department of Driver Services and local Tax Commissioner Offices may be required to increase its staff and provide additional training across the state. There are a few states whose experiences we can draw from in estimating these costs. For example, Maryland projected 230,000 new licenses would be issued over a four-year period, requiring 10 permanent and 55 temporary staff, and estimated its costs at $8.8 million. Illinois projected it would issue from 250,000 to 1 million new licenses, hire 100 people (including call operators for appointments) and require $800,000 in the first year and $250,000 annually thereafter.[27]

Based on the estimated number of new licenses that would be issued in Georgia—164,968, or approximately one-third less than what Maryland and Illinois predicted—the projected revenue ($17 million) would easily compensate for any additional costs, including staffing, outreach and translation services. A more accurate estimate of the projected costs of expanding driver’s cards in Georgia could be achieved through the request of a fiscal note, which is a written estimate of the costs, revenue or savings that can result from a bill’s implementation.[28]

Methodology

Number of undocumented immigrants of driving age and the number who would obtain a driver’s license during the first three years of implementation

Before narrowing to the number of undocumented immigrants of legal driving age, GBPI begins with the average of two population estimates for the total number of undocumented immigrants in Georgia: the Center on Migration Studies (CMS) (342,567) and the Pew Research Center (375,000).[29], [30] The CMS estimate uses microdata from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) that is reported through the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) and is recognized as a reliable estimate of local-level data. The Pew estimate is 2017 data based on augmented U.S. Census Bureau data. Based on the average of these, Georgia’s undocumented population is estimated to be 358,784 people.

To estimate the total number of undocumented immigrants who are eligible for a driver’s license because they are 16 years old or older, we first estimate the percentage of the total undocumented population in Georgia who are in this age range. Based on CMS’ estimate for the number of undocumented immigrants who are 16 years or older (314,870)—legal driving age in Georgia—GBPI calculated that 92 percent (314,870/342,567=.92) of Georgia’s undocumented population are over the age of 16. Ninety-two percent of GBPI’s estimated total of 358,784 Georgia undocumented results in an estimated 329,935 Georgia undocumented immigrants who are of driving age.

We estimate a 50 percent take-up rate for driver’s licenses among undocumented immigrants in Georgia within the first three years of implementation, resulting in 164,968 new driver’s licenses issued during this timeframe. This take-up rate is based on the experiences of other states that have passed legislation to allow undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses, estimates from other states on driver’s license take-up and data on Georgia drivers.[31]

After two full years of implementation, three out of the five states reporting saw between 34 percent and 40 percent take-up (34 percent in California, 36 percent in Washington, D.C., and 40 percent in Illinois). Of states that had reported a full three years of implementation, Nevada, which had low take-up rates all three years, saw 25 percent take-up and Illinois saw a jump to 47 percent take-up. Based on these take-up rates, the Fiscal Policy Institute in New York conducted a fiscal analysis on the impact of lifting restrictions on driver’s licenses using an estimated 50 percent take-up.[32]

This analysis compares Georgia data with that of Illinois and New York in particular to establish the likely take-up rate. All of these states have a high number of lane-miles, or miles of roads that are intended for driving. This is evidenced by the estimated lane-miles in each state as reported by the Federal Highway Administration in 2018: out of all states, Illinois ranks No. 3 (307,000 miles), and New York ranks No. 12 (239,000 miles); Georgia ranks No. 8 with 272,318 miles.[33]

Although Georgia may be similar to Illinois and New York in terms of lane-mileage, the availability of public transportation will influence how many residents use cars and apply for a driver’s license. Both Illinois and New York have extensive public transportation systems in Chicago and New York City, respectively, which is something Georgia lacks outside of limited portions of the Metro-Atlanta area. Yet, this availability did not impede the three-year take-up rate in Illinois (nor did it appear to in Washington, D.C., which is entirely urban and whose transit system is also notably robust). The New York analysis notes that 57 percent of New York City adults do have a driver’s license, which is taken into account when establishing their estimated 50 percent take-up rate.

Because Georgia does not have as extensive a public transportation system as Illinois, Washington, D.C. or New York, we would expect that the take-up rate for driver’s licenses would be higher in Georgia given that access to an alternative form of transportation is not as much a limiting factor and large pockets of the state’s undocumented population live in areas not serviced by the MARTA system.

Finally, the proportion of current adult drivers in a state provides context for the utility in having, and interest in obtaining, a driver’s license. Based on data from the Federal Highway Administration and the U.S. Census Bureau, 79 percent of adult residents in New York have a driver’s license, and 86 percent of adults in Illinois do; in Georgia, this number is 86 percent.[34] Since there is a comparable proportion of adults currently driving in Georgia as compared to Illinois and New York we would expect our take-up rate for driver’s licenses among the undocumented community to be in line with that of the higher end of the observable three-year data.

Number of new cars on the road

To project the number of new cars that might be purchased and registered in Georgia, we assume a 36.6 percent take-up rate of those who obtain driver’s licenses would purchase a car (164,968).[35] This percentage is based on the Fiscal Policy Institute in New York’s analysis of CMS IPUMS data (2010-2013), which compares vehicle ownership in two types of households: “households including an undocumented immigrant” and “other immigrant households.”[36] This analysis assumes that given access to driver’s licenses, undocumented immigrants would purchase vehicles at the same rate as other immigrants when also taking into account household income. Applying this percentage to the number of additional licenses expected in the first three years of implementation projects 60,378 newly registered vehicles in this timeframe or approximately 20,126 newly registered vehicles a year.

Revenue from the first three years of implementation

Gas-Related Tax Revenue

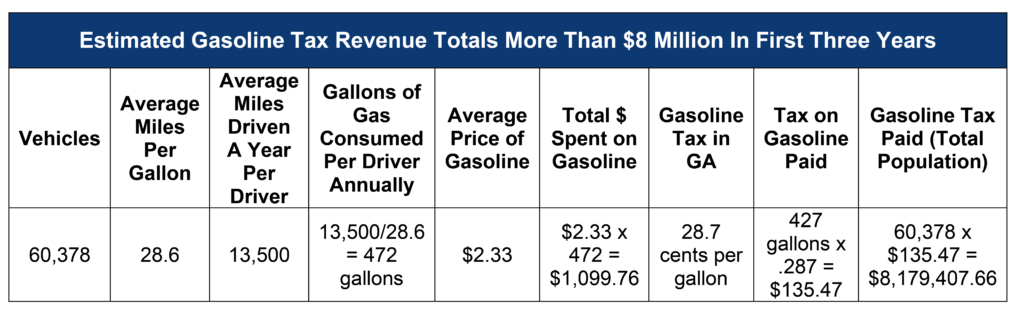

Gas-Related Tax RevenueGBPI’s analysis of gas-related taxes assumes the additional 60,378 cars that will be registered within the first three years of implementation were built in the last decade. The Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standard for new vehicles is reported by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics in miles per gallon (mpg).[37] The average mpg, considering both passenger cars and light trucks, from 2007 to 2017 (most recent data) is 28.6 mpg. (Note that if the cars purchased are older, this average mpg would decrease, in turn raising projected expenditure on gas and increasing related revenue; if newer, the reverse.) The Federal Highway Administration estimates that the average driver drives 13,500 miles per year but in Georgia vehicle miles per licensed driver average 18,920 miles per year.[38], [39]

Using the more conservative mileage estimate, GBPI estimates that drivers will consume 472.03 gallons of gasoline per year for the average vehicle made from 2007-2017. Using a point-in-time estimate based on the average prices in January 2021, GBPI assumes the price of gas is $2.33 per gallon and the average driver will spend $1,099.76 on gas per year.[40] Applying Georgia’s 28.7 cents-per-gallon gas tax to the lower cost of gasoline, the average driver will contribute $135.47 in taxes on gas to the state of Georgia per year.[41] By multiplying this amount by the projected number of new vehicles purchased, we obtain our estimated increase in gas taxes over the first three years of implementation.

End Notes

[1] National Council of State Legislatures, Immigrant Policy Project. (2008, July 24). State laws related to immigrants and immigration. https://www.ncsl.org/print/press/immigrationlegislationreport.pdf

[2] Georgia General Assembly, SB350 – Drivers’ Licenses; requirement; driving while licenses suspended/revoked; change certain provision. http://www.legis.ga.gov/legislation/en-US/display/20072008/SB/350

[3] Georgia General Assembly; HB 670 – Motor Vehicles; issuance of driving cards to noncitizen residents who are otherwise ineligible for a driver’s license, temporary permit or identification card; provide. https://www.legis.ga.gov/legislation/56218

[4] Along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, 16 states already provide access to a driver’s license or state identification card. These include: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, Virginia and Washington. See, National Immigration Law Center https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/drivers-license-access-table.pdf

[5] O.C.G.A. § 40-5-121 – Driving while licenses suspended or revoked.

[6] O.C.G.A. § 40-5-20 – License required; surrender of prior license; local licenses prohibited.

[7] O.C.G.A. § 40-5-121 – Driving while licenses suspended or revoked.

[8] Nagle, M. (2021, January 20). What to know about Joe Biden’s pathway to citizenship immigration plan. ABC. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/biden-pitch-year-pathway-citizenship-day-immigration-reform/story?id=75333490

[9] Tharpe, W. (2018). Voluntary immigration enforcement a costly choice for Georgia communities. https://gbpi.org/voluntary-immigration-enforcement-a-costly-choice-for-georgia-communities/

[10] U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Delegation of immigration authority section 287(g) Immigration and Nationality Act. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. https://www.ice.gov/287g

[11] Migration Policy Institute, Unauthorized Immigrant Population Profiles, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/us-immigration-policy-program-data-hub/unauthorized-immigrant-population-profiles

[12] Greenberg M. et al. (May 2019). Immigrant families and child welfare systems: Emerging needs and promising policies. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/ImmigrantFamiliesChildWelfare-FinalWeb.pdf

[13] Ibid.

[14] Redmon, J. (2020, November 6). New sheriffs to end immigration enforcement program in Cobb, Gwinnett. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/new-sheriffs-to-end-immigration-enforcement-program-in-cobb-gwinnett/ZXNYCGJKWVE27A2FB7HCYPQGNQ/

[15] Hallerman, T. (2021, January 1). New Gwinnett sheriff ends controversial immigration program. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-news/new-gwinnett-sheriff-ends-controversial-immigration-program/BTABR34VB5HF7JOIVLWTGT3HUY/

[16] Dixon, K. (2021, January 19). ‘New era in Cobb’: Sheriff ends controversial immigration enforcement program. Atlanta Journal Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-news/new-era-in-cobb-sheriff-ends-participation-in-controversial-immigration-program/FS3WCEQYIVEYRNFPQMCYCICQVQ/

[17] Georgia Department of Corrections. Total prison releases by home county for the past five fiscal years (FY 2016-2020). http://www.dcor.state.ga.us/sites/all/themes/gdc/pdf/Inmate_releases_by_county_by_FY.pdf

[18] National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2020). Domestic violence in Georgia. https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/ncadv_georgia_fact_sheet_2020.pdf

[19] Id.

[20] Georgia Unites Against Discrimination. (2016, July 1). Report: Georgia’s Transgender Population is 4th Highest. https://georgiaunites.org/wi-report/

[21] AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. (2011, November). Unlicensed to kill. https://www.adtsea.org/webfiles/fnitools/documents/aaa-unlicensed-to-kill.pdf

[22] Caceres, M. & Jameson, K. P. (2015, February 26). The effects on insurance costs of restricting undocumented immigrants’ access to driver licenses. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/soej.12022

[23] Moore, S. E. (2020, July). Six feet apart or six feet under: The impact of COVID-19 on the Black community. Death Studies, 1-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32609079/

[24] Clark, E., Fredricks, K, Woc-Colburn, L, Bottazzi, M. E., & Weatherhead, J. (2020, July). Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant communities in the United States. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14 (7). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7357736/

[25] Georgia Department of Revenue. Vehicle Taxes-Title Ad Valorem Tax (TAVT) and Annual Ad Valorem Tax. https://dor.georgia.gov/motor-vehicles/vehicle-taxes-title-ad-valorem-tax-tavt-and-annual-ad-valorem-tax#:~:text=TAVT%20is%20a%20one%2Dtime,Georgia%20for%20the%20first%20time.

[26] Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. The 2021 Georgia Budget Primer. https://gbpi.org/georgiabudgetprimer/

[27] The Pew Charitable Trusts. (2015, August). Deciding who drives: State choice surrounding unauthorized immigrants and driver’s licenses. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2015/08/deciding-who-drives.pdf

[28] Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. Fiscal note services. http://www.audits.ga.gov/legislativeServices.html

[29] Center for Migration Studies. (2018). State-level unauthorized population and eligible-to-naturalize estimates. http://data.cmsny.org/state.html

[30] Pew Research Center, Hispanic Trends. (2017). Unauthorized immigrant population trends for states, birth countries and regions. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/interactives/unauthorized-trends/

[31] Kallick, D. D. & Roland, C. (2017, January 31). Take-up rates for driver’s licenses: When unauthorized immigrants can get a license, how many do? Fiscal Policy Institute. http://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/FPI-Brief-on-Driver-Licenses-2017.pdf

[32] Id.

[33] U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, Federal-Aid Highway Lane – Length – 2018 (August 30,2019). https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2018/hm48.cfm

[34] U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, Licensed Drivers By Sex and Ratio to Population – 2018, (December 2019). https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2018/dl1c.cfm

[35] Note that new cars means new vehicle purchases, not necessarily a new vehicle model.

[36] Kallick, D. D. & Roland, C. (2017, January 31). Expanding access to driver’s licenses: How many additional cards might be purchased? Fiscal Policy Institute. https://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/FPI-Additional-cars-report-2017.pdf

[37] Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation, https://www.bts.dot.gov/content/average-fuel-efficiency-us-light-duty-vehicles

[38] U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration – Average Annual Miles per Driver by Age Group https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/onh00/bar8.htm

[39] U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration – State & Urbanized Statistics, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/onh00/onh2p11.htm

[40] AAA Gas Prices, Georgia Average Gas Prices (As of 1/18/20). https://gasprices.aaa.com/?state=GA

[41] Georgia Department of Revenue, Calculating Tax on Motor Fuel (See Gasoline State Excise Tax Rate). https://dor.georgia.gov/taxes/business-taxes/motor-fuel-tax/calculating-tax-motor-fuel