![]()

Key Takeaways

- Non-medical drivers of health, including access to safe, stable and affordable housing, shape most health outcomes.

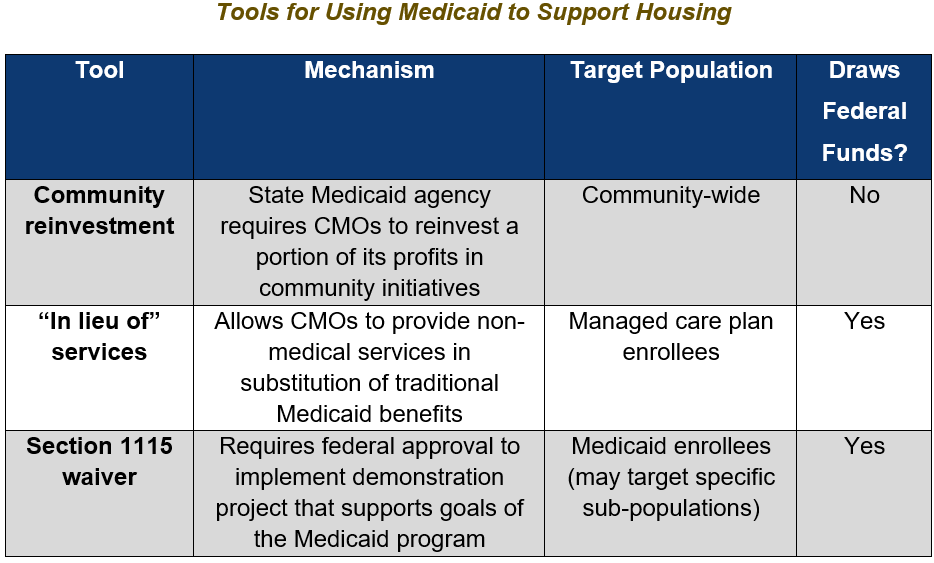

- States can leverage Medicaid funds to address health-related social needs using mechanisms such as community reinvestment, “in lieu of” services and Section 1115 waivers.

- Community reinvestment requirements mandate Medicaid care management organizations to reinvest a portion of their profits into initiatives that improve health for not only Medicaid members but entire communities.

- “In lieu of” services allow Medicaid managed care plans to offer medically appropriate, cost-effective substitutes for state plan-covered services including various housing supports.

- Section 1115 waivers allow states to test programs that support the goals of the Medicaid program and draw down federal funds for activities not usually covered by Medicaid.

- Georgia could take advantage of these opportunities to address the social determinants of health within its public healthcare system, lower health care costs and support holistic health among the state Medicaid population.

- Although potential changes to federal Medicaid policy may impact the immediate viability of using “in lieu of” services or Section 1115 waivers to address non-medical drivers of health, these policy tools still serve as potential long-term mechanisms through which the state could increase funding for housing support.

Introduction

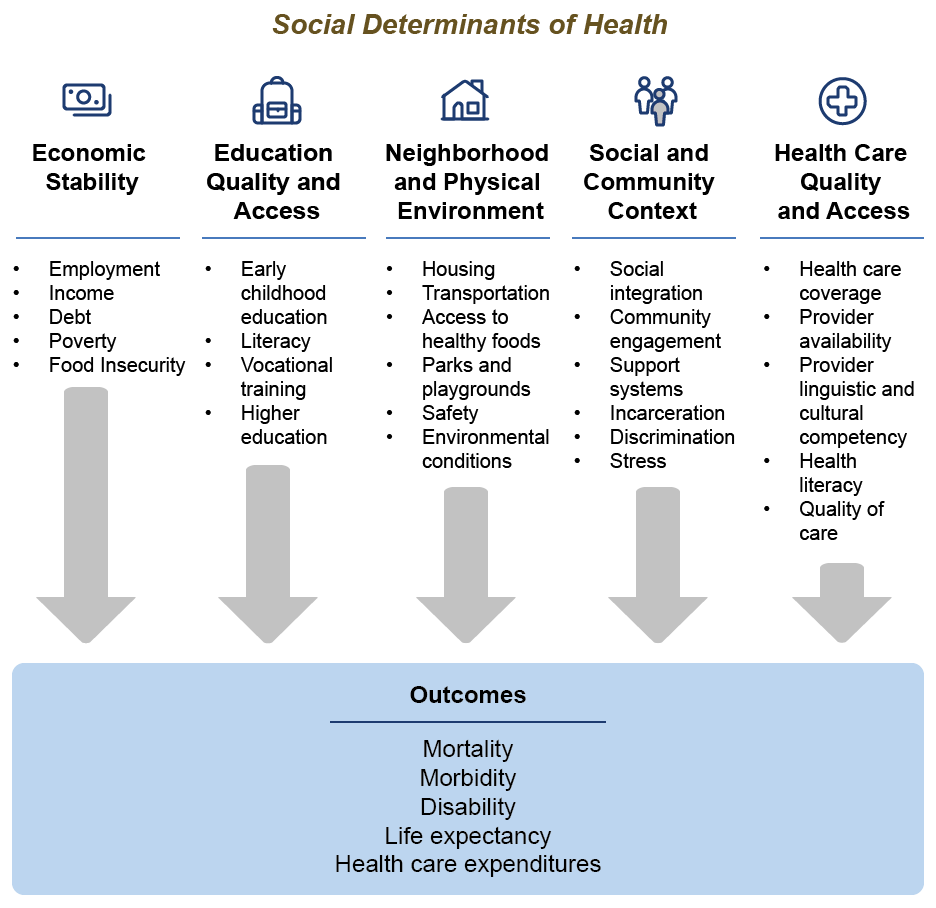

To achieve the strongest return on investment, state health spending should incorporate factors outside traditional medical care that shape a person’s ability to achieve optimal health. These factors, often referred to as the social determinants of health, are responsible for upwards of 90% of health outcomes.[1]

Among these social determinants of health is access to safe, stable and affordable housing. Unsafe housing can expose individuals to health hazards such as lead or mold, while housing instability can exacerbate stress, anxiety and other mental health issues.[2],[3] High housing costs can leave families strapped for cash, with fewer funds for other necessities including food, transportation and medical care.

Georgians are struggling to stay safely, affordably and stably housed:

- 46% of Georgia renters experience housing cost burden—in other words, they spend at least 30% of their income on housing costs.[4]

- 24% of Georgia renters experience severe cost burden, spending half or more of their income on housing.[4]

- While the issue of housing affordability is widespread, Georgians of color feel the burden at a disproportionate rate: 49% of Black renters and 47% of Latinx renters in Georgia experience cost burden compared to 36% of white renters in Georgia.[4]

Not only is housing becoming increasingly unaffordable for Georgians, but poor housing quality is putting Georgians’ health at risk:

- Over 15% of Georgia households experience a lack of plumbing, lack of complete kitchen facilities, overcrowding and/or severe cost burden.[7]

- One-third of Georgia homes were built prior to 1978 and may contain lead paint. In 17 Georgia counties, 29% or more of homes tested with high levels of radon, which can cause lung cancer with repeated exposure.[8]

Housing issues are both urgent in the current moment and enduring in their relevance. The struggle to access safe, affordable and stable housing has immediate implications for people’s lives as well as long-term effects on their health and wellbeing, and there will always be ways in which housing policy can be improved. Addressing the connection between Georgians’ health and housing needs requires a holistic approach that seeks to not only increase access to health care but work upstream to prevent the conditions that enable the proliferation of many preventable health issues as well. However, state funding for housing continues to lag what is needed to meet the severity of Georgia’s housing crisis. This report explores three mechanisms for funding housing supports through Medicaid to supplement—not supplant—existing federal and state appropriations for housing programs in Georgia: community reinvestment, “in lieu of” services and Section 1115 waivers. These mechanisms could contribute to a fully funded integrated health and human services system that supports holistic solutions to meeting Georgians’ health and housing needs.

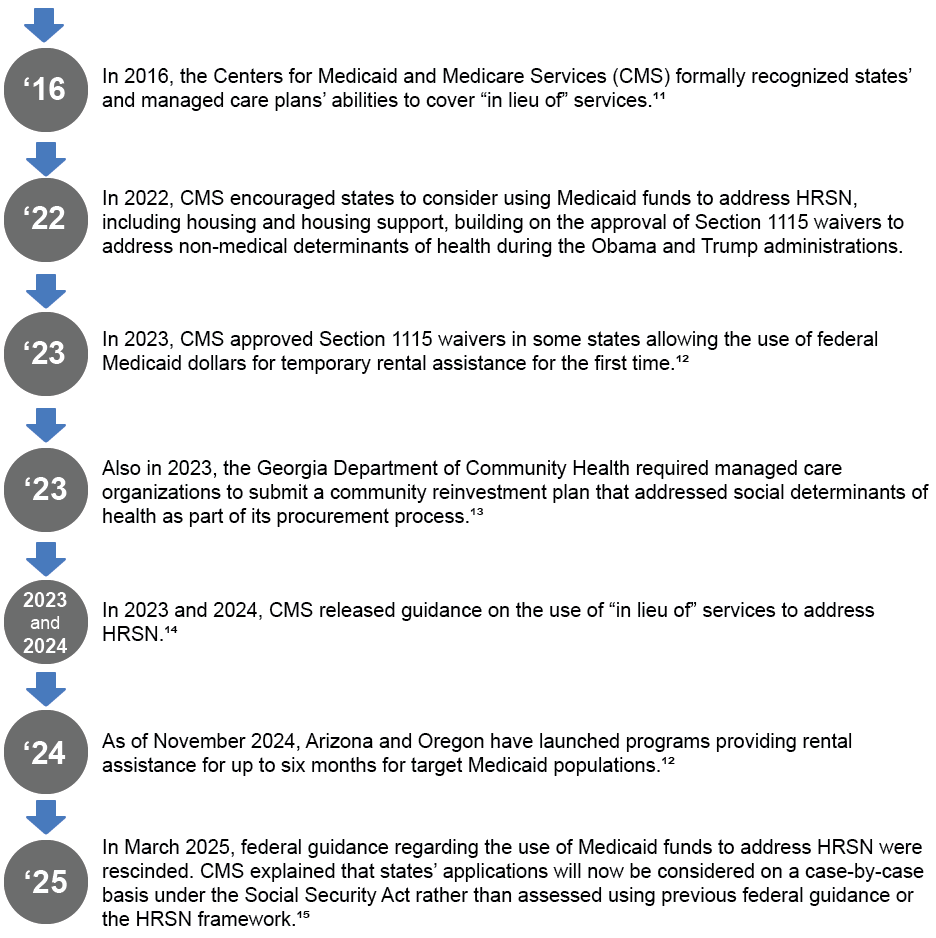

Medicaid and Health-Related Social Needs

Research suggests that many Medicaid patients experience health-related social needs (HRSN).[9],[a] Evidence indicates that housing improvements and interventions may not only improve health outcomes but also reduce health care costs in some cases.[10] Given this, federal and state Medicaid agencies have implemented several mechanisms to address non-medical drivers of health using Medicaid funds.

As states continue to innovate their approaches to addressing health and housing, community reinvestment, “in lieu of” services and Section 1115 waivers provide flexible opportunities for Georgia to follow suit and increase its investment in Georgians’ safety and well-being.

Addressing Housing Through Community Reinvestment

Through community reinvestment, state Medicaid agencies can leverage care management organizations (CMOs)[b] to address non-medical drivers of health by requiring them to reinvest a portion of their profits into initiatives to improve health for not only Medicaid enrollees but entire communities.[16],[17] As of September 2024, 10 states including Georgia either required or were in the process of developing community reinvestment policies for CMOs.

The Georgia Department of Community Health (DCH) began a bidding process for the state’s Medicaid managed care contracts in September 2023. DCH included in its request for proposals a requirement for CMOs to create a community reinvestment plan that identifies population health strategies in line with DCH’s Quality Strategic Plan and makes investments to address non-medical health risk factors such as housing.[18] Under this requirement, CMOs are allowed to include strategies to engage subcontractors, other CMOs, state agencies or community-based organizations in order to increase the impact of the activities undertaken using reinvestment spending.

While this requirement applies to new CMO contracts, CMOs in Georgia are already engaged in housing-related community reinvestment.[19] For example, CareSource has invested $3.5 million in affordable housing initiatives in Georgia. In 2022, CareSource invested $2.5 million with the Atlanta Neighborhood Development Partnership to support the acquisition and rehabilitation of 75 single-family homes in the Atlanta metropolitan area for affordable rental housing.[20] Later that same year, they announced a $1 million investment with the Volunteers of America to support the construction of new affordable housing as well as multifamily housing and a senior living complex in rural south Georgia.[21] Additionally, Amerigroup has participated in community reinvestment by providing a $400,000 grant to Wellspring Living to support a tiny home village for adult women survivors of sex trafficking in Kennesaw, Georgia.[18]

Although CMOs are required to have a community reinvestment plan as a part of their contract with DCH, community reinvestment contributions are voluntary in Georgia except in the case of required reinvestment due to a CMO not meeting Value-Based Payment performance targets.[17],[c] DCH also does not specify where community reinvestment funds should come from. Most other states that have implemented community reinvestment requirements have either required CMOs to reinvest a portion of their profits or reinvest or remit funds to the state if the CMO does not meet the minimum Medical Loss Ratio in a given contract year.[16],[17],[d] The inclusion of a community reinvestment plan requirement for CMOs in Georgia indicates a strong potential for Georgia to leverage Medicaid funds, including CMO profits, to address health-related social needs such as housing.

Addressing Housing Through “In Lieu of” Services

As of September 2024, over two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries in Georgia were enrolled in a managed care plan.[22] Federal Medicaid managed care rules allow CMOs to offer non-medical services in substitution of traditional Medicaid benefits, referred to as “in lieu of” services (ILOS).[23] ILOS must be optional to Medicaid patients and cannot be used to replace social services offered by other state or federal agencies.[24]

CMS guidance also asserts that states and CMOs do not have to demonstrate that a service creates “an immediate offset or reduction in the State plan-covered service or setting” for it to qualify as an ILOS. While ILOS must be cost-effective, they do not have to be budget neutral, and their cost-effectiveness can be measured over several years.[25]

How Can “In Lieu of” Services Be Used to Address Housing?

ILOS offer states a flexible avenue to address health and social needs using Medicaid funds, although there are some limitations to what services it can cover. ILOS can be used for housing support services such as providing air filters or a dehumidifier to a Medicaid enrollee with asthma to reduce the need for future asthma-related medical services, though federal guidance has generally prohibited them from used to cover room and board.[24] ILOS could cover services such as:

- First month’s rent as a transitionary service (i.e., if a housing deposit requires first month’s rent)

- Temporary placement of a Medicaid beneficiary into a nursing home or other institutional setting to give the beneficiary’s at-home caregiver a break from caretaking

- Housing transition and navigation services

- Pre-tenancy navigation services (e.g., conducting an assessment to identify housing preferences and barriers, housing search assistance, housing application assistance or move-in support)

- One-time transition and moving costs

- Tenancy sustaining services and case management

- Medically necessary home remediations (e.g., air conditioning or filtration improvements, refrigeration for medication, carpet replacement, mold removal or pest control)

- Home accessibility modifications (e.g., installing chairlifts, wheelchair ramps, railings or widening doorways)

Several states including Kansas and Iowa currently cover housing-related ILOS. In Kansas, ILOS can be used to cover home modifications that support a patient’s ability to function independently and create a safer, healthier environment to avoid placing a patient in a long-term care facility.[26] Kansas also covers comprehensive community support and transition assistance services for individuals transitioning out of institutional settings. Iowa includes pre-tenancy and tenancy sustaining services, housing transition navigation services (excluding deposits), case management and home modifications up to $4,000 per year as substitutes for nursing or intermediate care facility placement.[27]

Georgia could take advantage of its ILOS authority to address HRSN, including housing, among its Medicaid population. ILOS enables the state to use Medicaid funds to support non-medical health needs while circumventing the lengthy administrative process required to secure a Section 1115 waiver.[14] While they do not cover quite the same breadth of services that a Section 1115 waiver might, ILOS are still inclusive of many housing support services that would aid in housing Medicaid enrollees at risk of or experiencing homelessness, transitioning out of institutional care or living in unsafe and/or unhealthy homes. By using ILOS to get and keep Georgians housed, the state can work upstream to keep Georgians healthy and create cost savings down the line.

Addressing Housing Through Section 1115 Waivers

Section 1115 of the Social Security Act enables the Secretary of Health and Human Services to approve experimental programs that support the goals of the Medicaid program.[28] Section 1115 waivers give states flexibility by allowing them to deviate from certain Medicaid requirements to implement such a demonstration project and draw down federal matching funds for services not usually covered by Medicaid. They are initially approved for a 5-year period and can be renewed upon evaluation.[29]

Section 1115 waivers must follow certain fiscal guidelines. All Section 1115 waivers must be budget-neutral for the federal government.[30] For example, a state may identify savings created by the implementation of a demonstration that offset the cost of the program. As with ILOS, CMS guidance had specified that HRSN services offered through Section 1115 waivers are not intended to replace social services offered by other state or federal agencies, and state spending on social services offered prior to the waiver’s implementation must be maintained or increased.

How a North Carolina Section 1115 Waiver Addresses Housing Needs

North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots (HOP) program was approved as a Section 1115 waiver demonstration by CMS in October 2018 to spend up to $650 million in state and federal funds to address issues related to housing and other factors affecting high-needs Medicaid enrollees.[31] HOP began rolling out in March 2022, with housing/utilities and transportation services beginning in May 2022.

As of October 31, 2024, HOP has delivered over 668,000 services to over 26,700 enrollees and their families, equating to over $131 million in reimbursed services.[32] The efficiency of HOP’s payment model ensured the HSOs were able to operate successfully as Medicaid service providers, despite being historically dependent on grant funding for their operations.

Strong infrastructure has enabled North Carolina’s success in establishing multi-sector collaboration between the state, pre-paid health plans, healthcare systems, network leads and HSOs in the three regions serviced by HOP, as well as successful delivery of services.[33] Through a public-private partnership, North Carolina was able to develop NCCARE360, a statewide coordinated care network that connects individuals with identified needs to community resources.[27]

Between March 2022 and November 2023, housing needs were identified as the second-most common need among HOP participants, behind food. Over 65% of participants reported a housing need. Of those reporting a housing need, 68% received a housing service through HOP. Housing services provided by HOP include:

- Housing navigation, support and sustaining services

- Essential utility set-up; move-in support

- One-time payment of security deposit and first and last month’s rent

- Home remediation

- Safety and quality inspection

- Accessibility and safety modifications

- Healthy home goods

- Short-term post-hospitalization housing

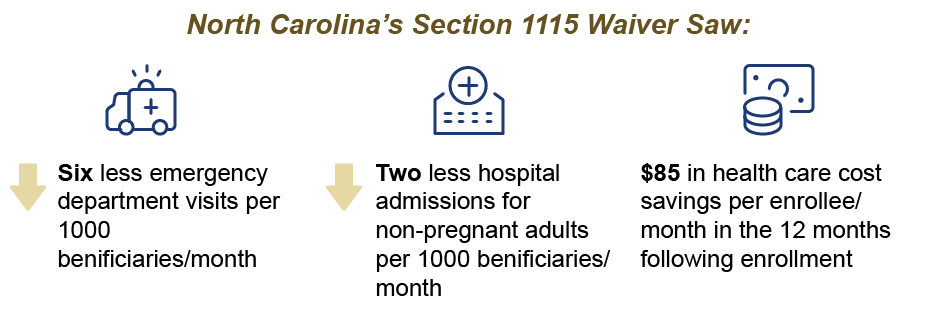

Results from an interim evaluation report of HOP suggest that the probability of a housing need decreases the longer a participant is enrolled in HOP.[34] Findings also indicate reduced emergency room utilization by emergency department visits per 1,000 beneficiaries per month, decreased hospitalization for non-pregnant adults at a rate of two admissions per 1,000 beneficiaries per month and health care cost savings of $85 per enrollee per month in the 12 months following enrollment.[32] Additionally, cost savings grew the longer a participant was enrolled in HOP, indicating that a participant’s decrease the longer they are enrolled in the program.[29]

HOP is notable for being the first program of its kind to operate on such a large scale. While some previous Medicaid programs reimbursed for limited non-medical services for small Medicaid sub-populations, HOP is the first Medicaid program to reimburse for a wide array of non-medical services for a breadth of Medicaid populations, including children and pregnant people.28 It is also able to offer services, such as household mold removal, that benefit not only a Medicaid enrollee but their whole family.

Given the promising results of the initial pilot program, North Carolina received federal approval to extend HOP for another 5-year period in December 2024.[35] The waiver renewal expands the program statewide and allows rental assistance up to six months as an eligible service.[36],[37]

What Could the Impact Be in Georgia?

As of August 2024, approximately 2 million Georgians—or 18% of Georgia’s total population—were enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP, known in Georgia as PeachCare for Kids). Medicaid provides health insurance to some of the most vulnerable in our state: 42% of children and 30% of people with disabilities in Georgia are Medicaid recipients.[38] Medicaid is also vital for health care access in communities of color, as 69% of non-elderly Medicaid enrollees are people of color.[39] An additional 240,485 uninsured adults could be eligible for Medicaid if Georgia were to close the coverage gap.[38],[e]

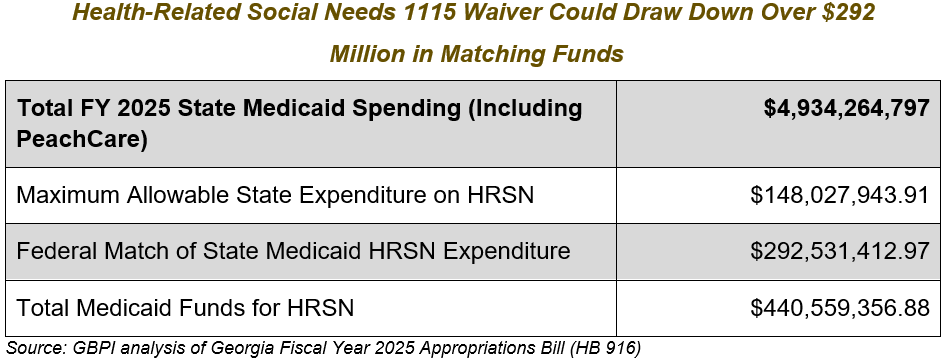

State funds spent on HRSN—both those expended through ILOS and Section 1115 waivers—are matched by the federal government at the standard Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage. As of FY 2025, Georgia’s standard Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage sits around 66%.[40] ILOS receive the federal match as they are services offered by managed care organizations and therefore reimbursable by Medicaid. Based on Georgia’s FY 2025 state Medicaid spending, the state could invest as much as $148 million in state funds to address social drivers of health through a Section 1115 waiver. This would allow Georgia to leverage over $292 million in federal matching funds to further fund these services as well.[41] In contrast, only about $35 million in state funds were allocated to housing programs in FY 2025.

While Medicaid funds cannot and should not accomplish all the same objectives as other sources of funding for housing, the state has a striking opportunity to support Georgians’ health and well-being by using a Section 1115 demonstration to strengthen social services infrastructure and provide housing support.

Housing Support for Rural Georgians

Housing support provided through a ILOS or Section 1115 waiver could be a lifeline for housing-insecure families in rural Georgia. As housing becomes more expensive statewide, rural Georgians have increasingly struggled to make ends meet.[42] This is especially true given that rural Georgians experience poverty at a higher rate than urban residents and often lack the social services and resources available in cities.[43],[44] Advocates have noted that many rural Georgians are forced to live in overcrowded homes to stay housed, and some individuals experiencing homelessness in rural Georgia are living in tent encampments in wooded or otherwise secluded areas due to a lack of emergency shelter.[41]

Many rural communities also struggle with the prevalence of unsafe housing conditions. A survey conducted by the University of Georgia showed that older housing units in need of maintenance and dilapidated housing in need of significant rehabilitation or demolition were identified as two of the most common housing issues in incorporated rural small towns in Georgia.[45] Georgians in rural counties also experience the greatest energy cost burden in the state due to several factors including poverty, unemployment and the prevalence of older, energy inefficient, single-family rental housing. Rural households with a household income less than 50% of the Federal Poverty Level (e.g., $16,075 or less annually for a family of four) spent a median of nearly 30% of their income on household electricity bills. Rural households between 50-99% of the Federal Poverty Level experienced an energy burden of approximately 16%.[46]

Rural Georgians are more likely to receive health insurance through Medicaid than Georgians living in urban areas: 13% of non-elderly rural adults are insured through Medicaid and 52% of children in rural areas are covered by Medicaid.[47] For rural Georgian Medicaid recipients struggling with housing, a Section 1115 waiver or ILOS policy could create access to housing resources such as home remediation, safety and accessibility modifications, utility assistance, and housing navigation, support, and sustaining services. By addressing health issues upstream through housing, rural Medicaid beneficiaries could also see health benefits like lower emergency room and hospital utilization as documented in North Carolina—a worthwhile consideration given the long-standing health care accessibility issues in rural Georgia, including health professional shortages and hospital closures.[48]

Housing Support for Georgians Living with Serious Mental Illness

Given the widespread impact of housing issues in Georgia, the state has an opportunity to deploy a Section 1115 waiver in ways that focus on key populations. For example, Arkansas, HRSN-related services offered through its Section 1115 waiver target three Medicaid sub-populations, including individuals in rural areas with serious mental illness (SMI) or substance use disorder (SUD).[49]

Mental health concerns have been on the rise in rural Georgia, with a majority of calls in Georgia to 988 (a national mental health crisis hotline) coming from rural Georgia, particularly south Georgia.[50] Suicide has increased in rural Georgia by over 66% in the last 20 years, and all rural counties in Georgia are considered mental health professional shortage areas.[51] Medicaid plays an important role in mental health treatment, acting as the largest funder of mental health and SUD services in the United States.[52] Between 2018 and 2019, 14.7% of adults with any mental illness in Georgia reported having Medicaid.[53] Medicaid enrollment is particularly high in South Georgia, especially southwestern Georgia. In 2023, Medicaid enrollees made up 20% or more of most South Georgia counties’ population.[54]

While housing interventions will not in and of themselves solve the mental health crisis in rural Georgia, they can help support access to housing for those with SMI or SUD and prevent exacerbated symptoms due to housing-related stress. Housing has proven integral to the treatment of SMI and SUD, with numerous studies indicating that Housing First models offer greater long-term housing stability than treatment first programs and reduce the length of hospital, residential substance abuse treatment and prison stays.[55] A Section 1115 demonstration project could take a Housing First approach,[f] providing temporary housing assistance and other housing supports to support for individuals with SMI and/or SUD, especially those transitioning out of institutional care or congregate settings.

Housing Support for Pregnant and Postpartum People

Georgia could build upon its adoption of 12-month postpartum coverage for pregnant people with a program providing housing support and case management to pregnant and postpartum people. Given that 46% of births and 40% of children in Georgia are covered by Medicaid, such a policy would have far-reaching implications for Georgia’s youth and familial outcomes.[36] Homelessness during pregnancy is associated with extreme preterm delivery, as well as increased maternal morbidity and mortality.[56] Georgia experiences one of the worst maternal mortality rates in the nation, and the risks are even higher for Black women.[57] Infants in households experiencing homelessness are more likely to be admitted into the neonatal intensive care unit, less likely to be enrolled in early childhood development programs and more likely to develop health conditions such as asthma, upper respiratory infections and developmental disorders.[53] By providing housing assistance and support to pregnant Medicaid enrollees, the state may be able to provide safeguards for some of the most vulnerable parents in our state.

Conclusion

Allowing the use of Medicaid dollars for housing assistance and support could be a crucial step toward supporting whole person health in Georgia. Georgia has already made moves in this direction by including a community reinvestment plan requirement in its most recent managed care plan procurement process, recognizing the important role non-medical factors play in individuals’ health outcomes. Several other states are already leveraging Medicaid funds to address the social determinants of health, including housing. Some, such as Kansas and Iowa, are taking advantage of ILOS authority—and the federal matching funds received by services offered by managed care organizations—to provide housing supports to managed care plan enrollees. Others, including North Carolina and Arkansas, have used Section 1115 waivers with promising results including lowered emergency room utilization, lowered non-pregnant adult hospital utilization and lowered health care costs.

Through a Section 1115 waiver, Georgia could enable the use of nearly $292 million in federal matching funds to address social drivers of health and uplift any number of the state’s vulnerable populations, such as rural Georgians, Georgians with serious mental illness or substance use disorder or pregnant Georgians and their young children.

Georgia can take advantage of lessons learned from policy tools implemented in other states to develop effective programs that not only elevate our state healthcare system but connects them with social services, community organizations, and other wraparound supports to create a truly comprehensive healthcare system that addresses every facet of Georgians’ health and well-being.

Acronym Glossary

CMO – Care management organization. Entity contracted with the state Medicaid agency to coordinate and manage services for Medicaid members.

CMS – Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Federal agency within the United States Department of Health and Human Services that oversees Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Health Insurance Marketplace.

DCH – Georgia Department of Community Health. Administers the state’s healthcare safety net, reimburses hospitals for services provided to uninsured and underinsured Georgians, manages health insurance coverage for state and school system employees and regulates health care and long-term care facilities. Responsible for administering Medicaid and CHIP in Georgia.

HOP – Healthy Opportunities Pilots. Section 1115 waiver demonstration in North Carolina providing non-medical interventions related to housing, food, transportation and interpersonal safety and toxic stress to high-needs Medicaid enrollees.

HRSN – Health-related social needs. Social and economic needs that individuals experience that affect their ability to maintain their health and well-being.

ILOS – “In lieu of” services. Policy tool that allows Medicaid managed care plans to offer medically appropriate, cost-effective substitutes for state plan-covered services.

SMI – Serious mental illness. A mental, behavioral or emotional disorder that substantially interferes with a person’s life and ability to function.

SUD – Substance use disorder. A treatable mental condition affecting a person’s brain and behavior characterized by the inability to control the use of a substance (or substances) despite harmful consequences.

Endnotes

[a] Although health-related social needs and social determinants of health are related terms, the two differ in scope. Social determinants of health refer to community-level social and economic factors that affect health outcomes, while health-related social needs refer to the specific individual-level factors that affect health outcomes. For more information, see: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (Accessed 2025, May 8). Social drivers of health and health-related social needs. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/social-drivers-health-and-health-related-social-needs

[b] “Managed Care is a health care delivery system organized to manage cost, utilization, and quality. Medicaid managed care provides for the delivery of Medicaid health benefits and additional services through contracted arrangements between state Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations (MCOs) that accept a set per member per month (capitation) payment for these services.” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (Accessed 2025, May 8). Managed Care. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care#:~:text=Managed%20Care%20is%20a%20health,accountability%20for%20high%20quality%20care

[c] “Value-based purchasing (VBP) refers to a broad set of performance-based payment strategies that link financial incentives to health care providers’ performance on a set of defined measures in an effort to achieve better value.” Damberg, C. L, Sorbero, M. E., Lovejoy, S. L., Martsolf, G. R., Raaen, L., & Mandel, D. (2024, Dec. 30). Measuring success in health care value-based purchasing programs. Rand Health Quarterly, 4, 3-9. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5161317/

[d] “The MLR is a comparison of how much of your premium goes towards paying medical claims compared to how much the insurer pays for administrative costs and keeps as profits. For example, an 82% MLR would mean that 82% of the total premiums paid by policyholders was going towards paying claims, and the other 18% was kept by the insurer for administrative expenses and profits. The MLR is important because it is used as a measure of the reasonableness of premiums.” New York State, Department of Financial Services. What is “medical loss ratio” or “MLR” and why does it matter? https://www.dfs.ny.gov/faqs/consumer-health/what-medical-loss-ratio-or-mlr-and-why-does-it-matter#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20an%2082%25%20MLR,of%20the%20reasonableness%20of%20premiums.

[e] “The coverage gap population is defined as uninsured adults aged 19-64 whose incomes are below the federal poverty level and who are ineligible for Medicaid because their states did not adopt the expansion. This includes parents whose incomes are above the eligibility limits for parents with children, and childless adults who wouldn’t be eligible at any income level.” Georgia Department of Community Health. (2024, August). Georgia Uninsured and Marketplace Data. https://dch.georgia.gov/document/document/georgia-uninsured-and-marketplace-data-august-2024-002/download

[f] “Housing First is a homeless assistance approach that prioritizes providing permanent housing to people experiencing homelessness, thus ending their homelessness and serving as a platform from which they can pursue personal goals and improve their quality of life. This approach is guided by the belief that people need basic necessities like food and a place to live before attending to anything less critical, such as getting a job, budgeting properly, or attending to substance use issues. Additionally, Housing First is based on the understanding that client choice is valuable in housing selection and supportive service participation, and that exercising that choice is likely to make a client more successful in remaining housed and improving their life.” National Alliance to End Homelessness. (Accessed 2025, May 19). Housing First. https://endhomelessness.org/resources/toolkits-and-training-materials/housing-first/

![]()

[1] Magnan, S. (2017, October 9). Social determinants of health 101 for health care: Five plus five. National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu/social-determinants-of-health-101-for-health-care-five-plus-five/

[2] Krieger, J., & Higgins, D.L. (2002). Housing and health: Time again for public health action. American Journal of Public Health. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1447157/

[3] Fallon, K. (2023, April 26). How does housing stability affect mental health? Urban Institute. https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/how-does-housing-stability-affect-mental-health

[4] Dong, H. (2024, July 17). How does Georgia fund housing? Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/how-does-georgia-fund-housing/

[5] The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2024, June 10). 2024 Kids Count data book: State trends in child well-being. https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-2024kidscountdatabook-2024.pdf

[6] The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2024, January). Children in low-income households with a high housing cost burden in Georgia. https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/71-children-in-low-income-households-with-a-high-housing-cost-burden#detailed/2/12/false/1095,2048,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868/any/376,377

[7] America’s Health Rankings. (Accessed 2024, September 30). Severe housing problems in Georgia. United Health Foundation. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/severe_housing_problems/GA

[8] National Center for Healthy Housing. (2024, May). Georgia 2024 healthy housing fact sheet. https://nchh.org/resource-library/fact-sheet_state-healthy-housing_ga.pdf

[9] Schiavoni, K. H., Helscel, K., Vogeli, C., Thorndike, A. N., Cash, R. E., Camargo, C. A., Jr., & Samuels-Kalow, M. E. (2022). Prevalence of social risk factors and social needs in a Medicaid Accountable Care Organization (ACO). BMC Health Services Research. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9675191/

[10] Whitman, A., De Lew, N., Chappel, A., Aysola, V., Zuckerman, R., & Sommers, B. D. (2022, April 1). Addressing social determinants of health: Examples of successful evidence-based strategies and current federal efforts. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e2b650cd64cf84aae8ff0fae7474af82/SDOH-Evidence-Review.pdf

[11] Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. (2023, January 3). RE: additional guidance on use of in lieu of services and settings in Medicaid managed care. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd23001.pdf

[12] Cohen, R. (2024, February 13). A prescription for housing? Vox. https://www.vox.com/2024/2/13/24064445/medicaid-rent-housing-homelessness-healthcare

[13] State Health & Values Strategies. (Updated 2024, October). Addressing health-related social needs through Medicaid managed care. Princeton University. https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/SHVS_Addressing-HRSN-Through-Medicaid-Managed-Care_October-2024.pdf

[14] Crumley, D. (2024, June). Using in lieu of services to address health-related social needs: Upshots from the recent federal rule. Center for Health Care Strategies. https://www.chcs.org/resource/using-in-lieu-of-services-to-address-health-related-social-needs-upshots-from-the-recent-federal-rule/

[15] Snyder, D. (2025, March 4). CMCS informational bulletin: rescission of guidance on health-related social needs. Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib03042025.pdf

[16] Snyder, D. (2025, March 4). CMCS informational bulletin: rescission of guidance on health-related social needs. Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib03042025.pdf

[17] Shippy, A., Silver, S., & McLendon, S. (2024, September 16). Community reinvestment: Forging new partnerships in Medicaid. Manatt, Phelps, & Phillips, LLP. https://www.manatt.com/insights/newsletters/health-highlights/community-reinvestment-forging-new-partnerships-in

[18] State of Georgia. (2023, September 22). State of Georgia contract between the Georgia Department of Community Health and [CMO] for the provision of Medicaid care management services (working draft). Georgia Procurement Registry. https://fscm.teamworks.georgia.gov/psc/supp/view/%7bV2%7d14ZudZ9ojO.ShnTaZt2HNXgoQOVpi6FEanhB0Z9t33ewUS82thSmbPORwzbCR0Cqkn9kxEZjKW2aRXh8K.PkjQMw1MmC20R0OlZLbBPdQElzBwOpwU0MU5it5tjAv1wNOPvS.dgMvhfL4LgKMAFK1PTAIzIHFwmZpN7ePMOGrdSGgv7Fj4dckXnk6IgqampvNGD51ktcmOf_ehQIvFTQLe5.UB_Vx7b81m_FxfuUnnDt_uOrTkfJV.D_RfDjbpaWSHA-/Attachment_F__CMO_GF_MODEL_Contract.pdf

[19] Health Management Associates. (2025, April 23). Maximizing collective impact: Navigating Georgia’s Medicaid reinvestment requirement with federal insights and collaborative solutions [Webinar]. https://healthmanagement.zoom.us/rec/play/BZL81fEuxCNFJAdPPiFheLBWo912XmS5isug1VpqqA_eugbXicecYoT-ZeJFoeOxhA6L0zGJrgcL-_Iz.9eA5TAv4-nONuE4V?accessLevel=meeting&canPlayFromShare=true&from=share_recording_detail&startTime=1745413254000&componentName=rec-play&originRequestUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fhealthmanagement.zoom.us%2Frec%2Fshare%2FM3cyO36GBrAAv8Lt33FoXgXTKmO-Ts8YTo03n8WNIvnig35Moh_spJljQlfC5i5W.RStLBq04zbjQXeoH%3FstartTime%3D1745413254000

[20] CareSource. (2022, September 14). CareSource invests $2.5M in Atlanta housing. https://www.caresource.com/newsroom/articles/caresource-invests-2-5m-in-atlanta-housing/

[21] CareSource. (2022, October 5). CareSource invests $1M to support affordable housing in rural Georgia. https://www.caresource.com/newsroom/press-releases/caresource-invests-1m-to-support-affordable-housing-in-rural-georgia/

[22] Georgia Department of Community Health. (Accessed 2024, November 22). Medicaid managed care. https://dch.georgia.gov/medicaid-managed-care

[23] Cuello, L. (2024, May 23). Strengthened tool to address health-related social needs: The new Medicaid managed care regulation’s “in lieu of services” explained. Georgetown Center for Children and Families. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2024/05/23/strengthened-tool-to-address-health-related-social-needs-the-new-medicaid-managed-care-regulations-in-lieu-of-services-explained/

[24] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2023, November). Coverage of health-related social needs (HRSN) services in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/hrsn-coverage-table.pdf

[25] Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2024, May 10). Medicaid program; Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) managed care access, finance, and quality. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/05/10/2024-08085/medicaid-program-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip-managed-care-access-finance

[26] KanCare. (2024, July 1). KanCare in lieu of services. https://www.kancare.ks.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/1402/638576006967370000

[27] Iowa Department of Health and Human Services. (2024, June 19). IA Health Link SFY25 rate certification appendix III. https://hhs.iowa.gov/media/13960/download?inline

[28] National Diabetes Prevention Program Coverage Toolkit. (Accessed 2024, September 30). Attaining coverage through a Section 1115 demonstration waiver. https://coveragetoolkit.org/medicaid/medicaid-coverage-2/medicaid-1115-demonstration-waivers/

[29] NAMD Staff. (2024, April 17). Medicaid innovation pathway: How 1115 waivers work. National Association of Medicaid Directors. https://medicaiddirectors.org/resource/how-1115-waivers-work/

[30] Hinton, E., & Amaya, D. (2024, March 4). Section 1115 Medicaid waiver watch: A closer look at recent approvals to address health-related social needs (HRSN). KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/section-1115-medicaid-waiver-watch-a-closer-look-at-recent-approvals-to-address-health-related-social-needs-hrsn/

[31] Van Vleet, A. (2024, March 17). Reflecting on nearly two years of North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots. North Carolina Medical Journal. https://ncmedicaljournal.com/article/94844-reflecting-on-nearly-two-years-of-north-carolina-s-healthy-opportunities-pilots

[32] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (Accessed 2024, November 22). Healthy Opportunities Pilots at work. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/healthy-opportunities-pilots/healthy-opportunities-pilots-work

[33] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (2024, April 4). Healthy Opportunities Pilots interim evaluation report summary. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/documents/healthy-opportunities-pilots-interim-evaluation-report-summary/open

[34] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (2024, April 16). NC Healthy Opportunities Pilots interim evaluation report. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/healthy-opportunities-pilots-interim-evaluation-report/download?attachment

[35] Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2025, January 16). Demonstration approval. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/nc-technical-correction-ltr-01162025.pdf

[36] NCTracks. (2024, December 14). NCDHHS receives 1115 Medicaid waiver approval. https://www.nctracks.nc.gov/content/public/providers/provider-communications/2024-Announcements/NCDHHS-Receives-1115-Medicaid-Waiver-Approval.html

[37] Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2024, December 18). CMS approval – HOP post-approval protocols. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/nc-medicaid-reform-demo-dmnstrn-aprvl-12182024.pdf

[38] Georgia Department of Community Health. (2024, August). Georgia uninsured and marketplace data. https://dch.georgia.gov/document/document/georgia-uninsured-and-marketplace-data-august-2024-002/download

[39] KFF. (2024, August). Medicaid in Georgia. https://files.kff.org/attachment/fact-sheet-medicaid-state-GA

[40] KFF. (Accessed 2024, November 26). Federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and multiplier. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[41] GBPI analysis of: Georgia Fiscal Year 2025 appropriations bill (HB 916). 157th Georgia General Assembly. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/appropriations-bills/hb-916-fy-2025-appropriations-bill/download

[42] U.S. Federal Housing Finance Agency. (Accessed 2025, May 19). All-transactions house price index for Georgia [GASTHPI]. Federal Reserve Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GASTHPI

[43] Georgia Health Initiative. (2024, February). Closing the coverage gap: policy considerations for public-private solutions to expand health insurance in Georgia. https://georgiahealthinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Closing-the-Coverage-Gap.pdf

[44] Grapevine, R. (2022, August 29). Homelessness a problem in rural Georgia. Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://www.gpb.org/news/2022/08/29/homelessness-problem-in-rural-georgia

[45] Skobba, K., & Tinsley, K. (2019, October 29). Survey of rural small town housing in Georgia. UGA Housing and Demographics Research Center. https://www.fcs.uga.edu/docs/GA_Small_Town_Housing_Survey_Report-102919.pdf

[46] Moleka, E. (2022, March). A call to action: Analyzing rural energy burdens in Georgia. Groundswell. https://groundswell-web-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/GA+rural+ENERGY+burdens.pdf

[47] Osorio, A., Alker, J., Park, E. (2023, August 17). Medicaid’s coverage role in small towns and rural areas. Georgetown Center for Children and Families. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2023/08/17/medicaids-coverage-role-in-small-towns-and-rural-areas/

[48] Burton, A. (2023, September 8). In rural Georgia, Senate study committee looks at how to address medical workforce concerns. Georgia Public Broadcasting. https://www.gpb.org/news/2023/09/08/in-rural-georgia-senate-study-committee-looks-at-how-address-medical-workforce

[49] KFF. (2024, November 1). Medicaid waiver tracker: approved and pending Section 1115 waivers by state. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/

[50] Williams, D. (2023, October 26). Rural Georgians suffering disproportionately from mental health issues. Capitol Beat. https://capitol-beat.org/2023/10/rural-georgians-suffering-disproportionately-from-mental-health-issues/

[51] Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. (2023, October). Media briefing: Farm workers mental health in Georgia. https://dbhdd.georgia.gov/document/document/farmers-mental-health-oct-2023-fact-sheet-dbhddpdf/download

[52] National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2025). Medicaid & mental health in Georgia. https://www.nami.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Georgia_NAMI-Medicaid-State-Fact-Sheet.pdf

[53] KFF. (2023, March 20). Mental health in Georgia. https://www.kff.org/statedata/mental-health-and-substance-use-state-fact-sheets/georgia/

[54] Center for Children and Families. (Accessed 2025, May 8). Medicaid coverage in metro and small town/rural counties in Georgia, 2023. Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2025/01/14/medicaid-coverage-in-metro-and-small-town-rural-counties-in-georgia-2023/

[55] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research. (2023). Housing First: A review of the evidence. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/spring-summer-23/highlight2.html

[56] Gardner, A., Mondestin, T., Kaneb, N., & St. Goar, J. (2024, June 13). State use of Section 1115 demonstrations to support the health-related social needs of pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and young children. Georgetown Center for Children and Families. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2024/06/13/state-use-of-section-1115-waivers-to-support-the-health-related-social-needs-of-pregnant-and-postpartum-women-infants-and-young-children/#heading-5

[57] Libers, A. (2023). Fighting the maternal mortality crisis. Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. https://sph.emory.edu/features/2023/06/maternal-mortality/#:~:text=In%20fact%2C%20Georgia’s%20maternal%20mortality,per%20the%202021%20CDC%20report