Thank you to Mandy Alderman of COVID Survivors for Change for sharing her personal story.

In 2021, COVID-19 was the leading cause of premature death in Georgia, and, in mid-2022, the United States overall passed the dismal milestone of 1 million deaths from COVID-19. As COVID-19 recedes from the news headlines, it is important to maintain focus on the long-term health impacts of the pandemic and proactively plan for the future. In particular, we should consider the implications of children who have lost a caregiver to COVID-19 and adults who are experiencing long COVID symptoms.

Thousands of Children in Georgia Have Lost a Caregiver to COVID-19

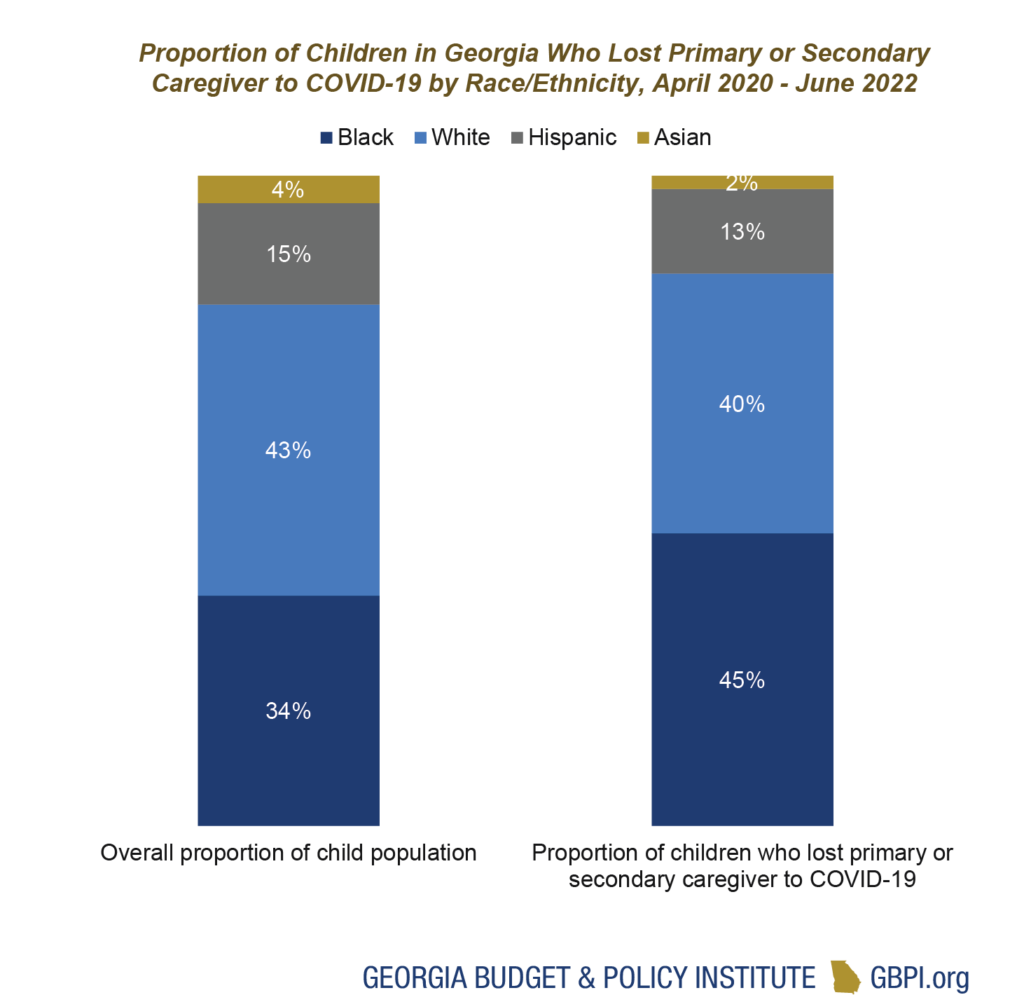

An estimated 11,725 children in Georgia under 18 years old have lost a primary or secondary caregiver to COVID-19 from April 2020 to June 2022.[1] That includes the death of one or both parents and/or the death of grandparents who live with and provide at least some support for the child. Some children are more affected by this caregiver loss than others. International data show that a disproportionate burden of COVID-19-related caregiver loss falls on young adolescents ages 10-17 years old and that children are more likely to lose a father than a mother. Due to long-standing structural inequities, like occupational segregation and labor exploitation, Black workers faced increased occupational exposure to COVID-19 as frontline workers and barriers to accessing the health care needed to prevent and treat COVID-19 infection. As a result, Black adults experienced increased risk of death from COVID-19 and Black children faced greater risk of caregiver loss. Though Black children in Georgia represent 34% of the child population, they account for 45% of the children who lost a primary or secondary caregiver to COVID-19. In other words, roughly 1 in every 215 children overall and 1 in 160 Black children in Georgia have experienced the loss of a caregiver due to COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic.

Source: GBPI analysis of data from KIDS COUNT (datacenter.kidscount.org) and Global Reference Group on Children Affected by COVID-19 (imperialcollegelondon.github.io/orphanhood_USA)

Hundreds of Thousands of Georgians Report Having Long COVID Symptoms

Post-COVID-19 conditions, often known as long COVID, are symptoms that the person did not have prior to their COVID-19 infection and that last three or more months after first contracting the virus. Symptoms range from tiredness and chest pain to difficulty concentrating and muscle pain. Studies of electronic health records among the general population and among veterans have found that COVID-19 survivors have increased risk for developing blood clots to the lungs, breathing issues, stroke, memory problems and a range of other conditions—even among people who did not require hospitalization during their COVID-19 infection.

According to a self-report survey from late July to early August 2022, about 1 in 5 of the Georgians who have had COVID-19 reported currently having long COVID symptoms. Applying the results of this survey, an estimated 715,276 of all adult Georgians are currently experiencing long COVID.[2] Georgia-specific demographic data are not available; however, national estimates indicate that women, Hispanic adults and working age people were more likely to report experiencing long COVID symptoms.

COVID-19’s Long-Term Health Impacts Have State Budgetary and Policy Implications

Georgia continues to have COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths. That means the numbers of Georgians impacted by the loss of a caregiver or by long COVID will only increase. It is critical that we as a state consider both the human toll of this loss and sickness as well as the implications for state planning.

Increased health care and human service needs

- The loss of a parent is an adverse childhood experience, or ACE. ACEs can have negative effects on life opportunities like education and job potential and are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance use disorder in adolescence and adulthood. Effective action (e.g., keeping children in their families even if a parent/caregiver dies and providing economic supports as needed; ensuring grieving children have access to behavioral health care and support services) can mitigate the harm of parent/caregiver loss; however, it will require additional, sustained support from Georgia’s health care and human service systems.

- Similarly, Georgians with long COVID who are no longer able to work could lose their existing employer-based insurance, which may increase demand for alternate sources of coverage like Medicaid. Additionally, more Georgians with long COVID who already have Medicaid may be seeking specialized health care services to address their long COVID symptoms.

Lower workforce participation and lost earnings

- A recent analysis estimates that about 1.8% of the U.S. labor force is out of work due to long COVID, and they are missing out on $168 billion a year in lost earnings. Additional research is needed to understand the impact of long COVID on Georgia’s workforce. However, extrapolating national estimates to Georgia makes it clear that, without intervention, long COVID could have serious consequences on workforce participation, individual financial stability, and Georgia’s economy.

Deepening inequity

- Georgians who already faced persistent and systemic barriers to good health prior to the COVID-19 pandemic—including Black and Latinx Georgians with lower incomes, rural Georgians and Georgians with disabilities—are likely to be disproportionately affected by the long-term health impact of COVID-19. Poverty and structural racism, in particular, create the harmful conditions—like inequitable access to health care and occupational segregation —that make exposure to COVID-19 and its long-term health impacts harder to avoid. Without intentional planning, Georgia risks further compounding existing inequities.

- For example, data indicate that rural Georgia communities suffered a disproportionate number of COVID deaths relative to their population size; the Georgia counties with the highest COVID-19 death rates—like Hancock, Terrell, and Treutlen—are all rural counties.[3] There is no data available on the prevalence of long COVID among Georgians living in rural vs. urban communities. However, researchers suggest that barriers to accessing the care needed to prevent and treat COVID-19 infection coupled with a tendency toward older populations with more chronic conditions puts rural populations at increased risk for long COVID.

Mandy Alderman, a white 44-year-old COVID “long hauler” in Gwinnett County, says she was terminated from her job as a medical assistant after getting sick with COVID in late 2020 and being unable to return to work. Alderman says that trying to treat and manage her condition (having at least four to five different doctors amongst primary care, cardiology, pulmonology, and neurology) after losing her employer-based health insurance was “absolutely terrifying.”

Alderman was able to secure a Healthcare.gov plan that made her post-COVID care costs “manageable” at first. However, after resolving an issue with her initial Healthcare.gov application process, Alderman’s documented income (which was $0 since she was unable to work) caused her new monthly premiums and plan deductibles to soar since she no longer qualified for marketplace subsidies. She was also notified that she didn’t qualify for Medicaid. Now, Alderman says she can’t afford the lung and neuropathy prescription medications needed to treat her long COVID symptoms.

Georgia’s Legislature Can Take Proactive Steps to Plan for COVID-19’s Long-Term Impact

Georgia’s state legislature can take proactive steps to plan for COVID-19’s long-term impact upon our state. National- and state-level data on the impact of caregiver loss and long COVID are sparse, and more research is needed to help guide decision-making and resource allocation. However, existing data point to several initial policy options.

Children’s COVID-19 survivor fund

-

- Create of a fund using American Rescue Plan or state funding to provide support for children who have lost a primary caregiver to COVID-19 that is either short-term (e.g., unconditional cash transfers) or long-term (e.g., ‘baby bonds’ or trust funds).

- Examples of similar programs include California’s HOPE for Children Act ($100 million allotted in their current state budget) and the 9/11 victim compensation fund.

- Create of a fund using American Rescue Plan or state funding to provide support for children who have lost a primary caregiver to COVID-19 that is either short-term (e.g., unconditional cash transfers) or long-term (e.g., ‘baby bonds’ or trust funds).

Paid family and medical leave

- Expand Georgia’s existing paid parental leave into a fully-resourced paid family medical leave program to give Georgia state and public-school employees with long COVID or state and public-school employee caregivers the support they need to care for themselves or their loved ones while also maintaining employment.

- Consider expanding paid family and medical leave to the private sector by creating a family and medical leave insurance program that helps reduce the share of employees showing up sick to work with COVID-19 (thus reducing the risk of developing long COVID).

Medicaid expansion

- Fully expand Medicaid to ensure that adults with low incomes have access to the affordable health care they need to manage their long COVID symptoms.

Study committee on long-term health impacts of the pandemic

- Create a study committee to better understand and develop a plan for addressing the long-term health impacts of COVID-19

- Issues to consider (in addition to those above) include disability benefits, workers compensation and more.

[1] Based on GBPI analysis of: Global Reference Group on Children Affected by COVID-19 (2022). COVID-19-Associated Orphanhood and Caregivers Death in the United States [Data set]. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://imperialcollegelondon.github.io/orphanhood_USA/

[2] Based on GBPI analysis of: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Household Pulse Survey-Long COVID [Data set]. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.htm

[3] Based on GBPI analysis of: Georgia Department of Public Health (2022). Georgia DPH COVID-19 Status Report [Data set]. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://ga-covid19.ondemand.sas.com/