Recommendations to Eliminate the Cliff Effect in Georgia’s Safety Net Programs

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) program act as safety nets for many hardworking Georgians by providing a line of defense against poverty, fulfilling basic needs and encouraging economic mobility. Specifically, these supports are essential for helping parents with young children find jobs, remain employed longer and keep food on the table.

As a result, children grow up in economically secure households, have fewer disruptions in their education and experience better health. Yet too many working families are unable to maximize the full potential that the safety net can offer, especially in Georgia. Due to harsh eligibility rules, participants are often cut off from the programs once they begin to see slightly modest increases in earnings, choose to pursue a postsecondary education or fail to meet difficult reporting requirements. This cut off, commonly known as the ‘cliff effect’[1], sets families back on their path to self-sufficiency.

By eliminating crucial resources, the cliff effect guarantees that pay raises do not always equal improvements in financial security. Despite their effectiveness, safety net programs can be improved so that hardworking parents are not forced to choose between upward mobility and keeping critical assistance that benefits the entire family. Declining opportunities to move up the economic ladder can keep parents from improving their family’s long-term prosperity and contributing to the state’s economy by limiting the ability of more Georgians to become financially secure.

Programs such as SNAP and CAPS provide much-needed resources to families while also encouraging parents to work. This policy report highlights the effects of work support programs on Georgians who earn low incomes while illuminating the difficult choices working parents need to make due to counterproductive program rules. In addition, this report proposes policy changes that can help Georgians mitigate the cliff effect by ensuring they can support their family in the short-term while building a more financially secure life for the long-term.

The goals of all safety net programs are the same: encourage work, promote family economic security and well-being, and eliminate poverty. To ensure programs achieve those goals, Georgia lawmakers should look to make program improvements by considering the following recommendations:

- Streamline public assistance program reporting requirements

- Raise SNAP’s categorical eligibility gross income limit from 130 percent to 200 percent of federal poverty guidelines

- Help families avoid cliffs by raising the initial income limits for entering the child care subsidy program

- Implement transitional child care assistance for parents who are unable to meet work requirements or exceed income limits

- Extend eligibility for child care subsidies to 4-year college students

What it Takes to be Self-Sufficient in Georgia

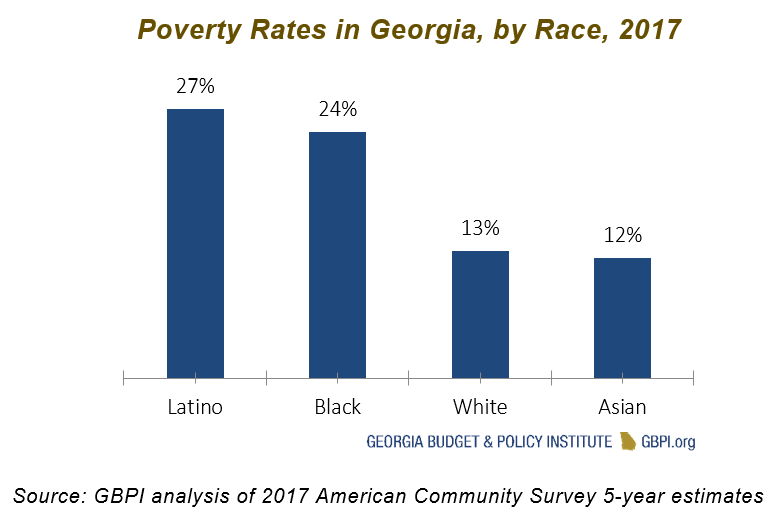

Georgia’s story is no different than that of many other states, especially those across the South. A staggering 3.6 million Georgians live below 200 percent of the federal poverty level or make $24,000 a year or less. Safety net programs are particularly crucial for Georgians of color who also disproportionately live in poverty. About 1 in 4 Latino and black Georgians live below the poverty line or make $25,100 a year for a family of four.[2]

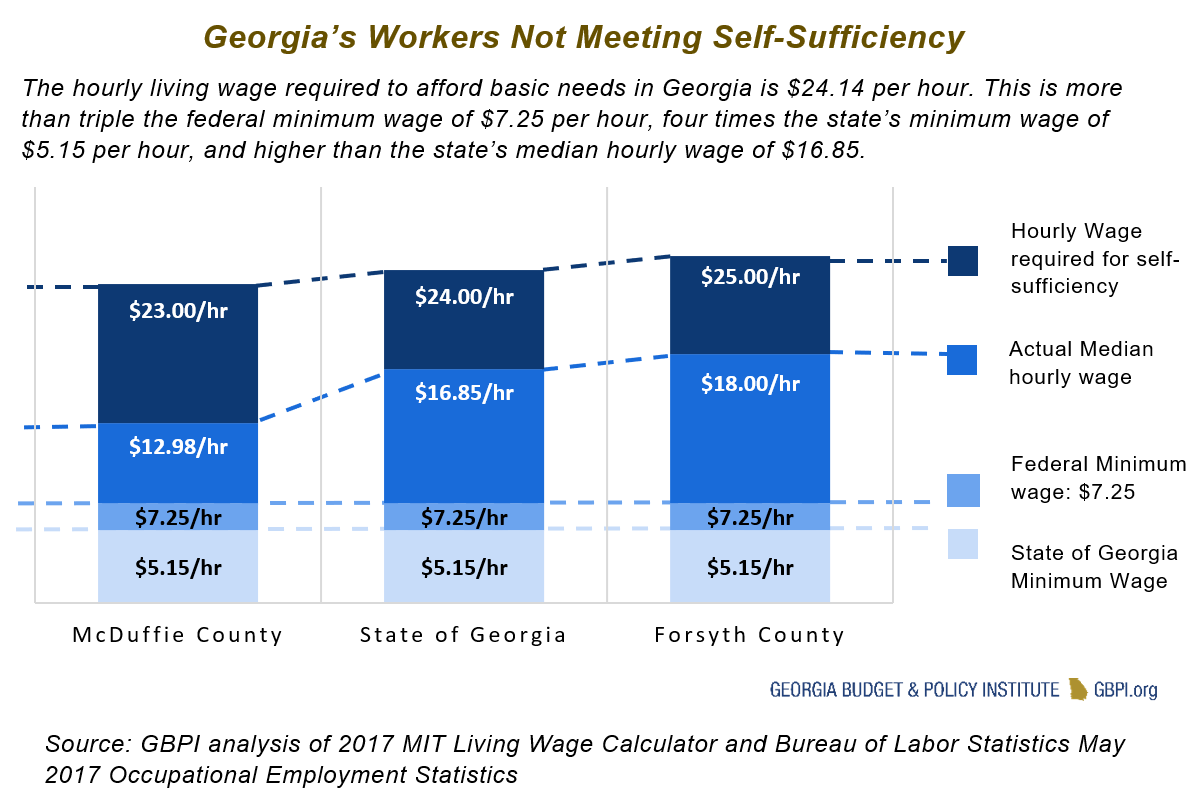

In Georgia, a typical household with one adult, one child needs about $50,000 a year (2,080 hours for a full-time worker) to cover basic expenses. This is also known as the living wage standard for the state. This measure in Georgia was developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and defines the amount of income (including taxes) needed to meet basic needs without public subsidies (e.g. food stamps or child care). The standard is higher than actual hourly wages earned by workers across the state. For example, Forsyth County has an annual living wage of $52,000, while McDuffie County’s living wage is roughly $48,000. In both counties the living wage exceeds the actual median wages of workers.[3]

The Safety Net is Powerful Policy

The high costs of child care, poor transportation options and the lack of jobs that pay sufficient wages are barriers to economic opportunity in Georgia. Safety net programs bridge the gap between the rising costs of basic needs and the low wages of workers. Designed to encourage work and upward mobility, these programs lifted millions of Georgians out of poverty in the last decade.[4]

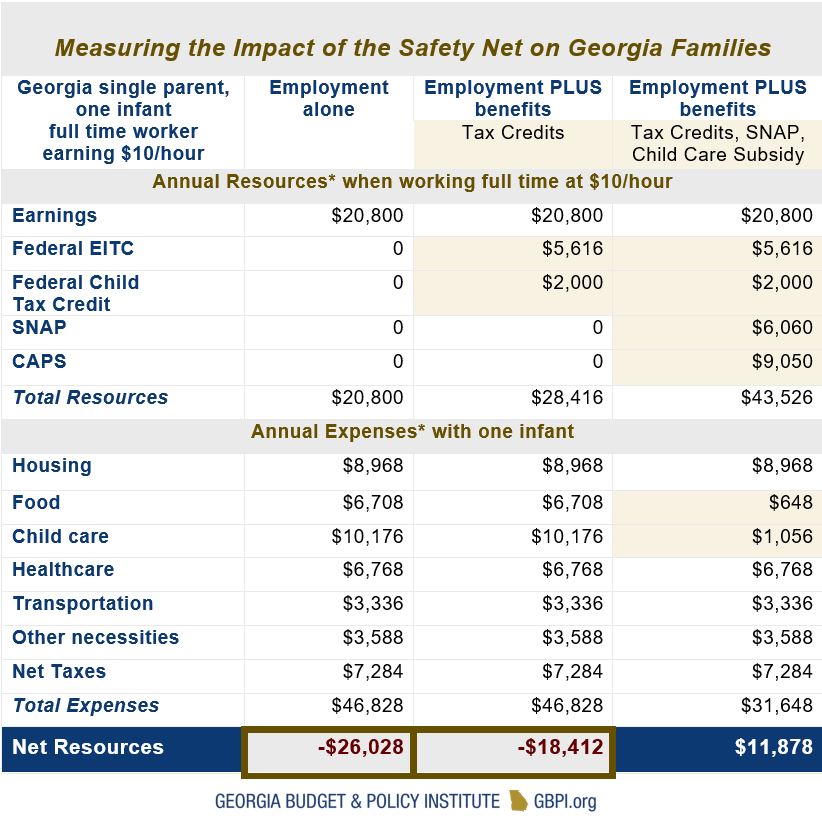

Low wages do not provide enough income for families to fully participate in today’s economy and achieve self-sufficiency. A single parent of one who earns a minimum wage of $7.25 per hour would spend a quarter of their paycheck on food alone every month. Even for parents earning slightly more than minimum wage, safety net programs play a critical role in helping them provide for their families. The table below demonstrates the important boost that food assistance, child care subsidies and tax credits play in helping Georgia families reach self-sufficiency and afford basic needs for a single parent with one infant.

*Note: Annual resources: Gross annual earnings based on full-time work for $10/hour, Federal EITC and Child Tax Credit amounts based on IRS rules for one parent, one dependent[5], SNAP amount based on USDA benefit calculation for two-person household[6], and CAPS amount based on value for one infant in care receiving quality rated discount[7]; Annual expenses are based on Self-Sufficiency Standard for Georgia.[8]

Consequences of Cliffs in Georgia’s Safety Net Programs

Safety net programs that have income thresholds or work activity requirements are well known for the cliff effect. When an individual abruptly loses their assistance because of changes in income or work activities, it causes major disruptions to economic mobility, often by forcing individuals to turn down pay raises or opportunities to pursue higher education. The general income eligibility requirements for safety net programs are well below 200 percent of the federal poverty line. Some programs include rules to ensure that benefits smoothly phase out over time with increases in income. Despite the phase-out, the abrupt loss of supports at income levels less than Georgia’s living wage standard of $50,000 a year can throw up a major hurdle for Georgians working hard to move up the economic ladder.

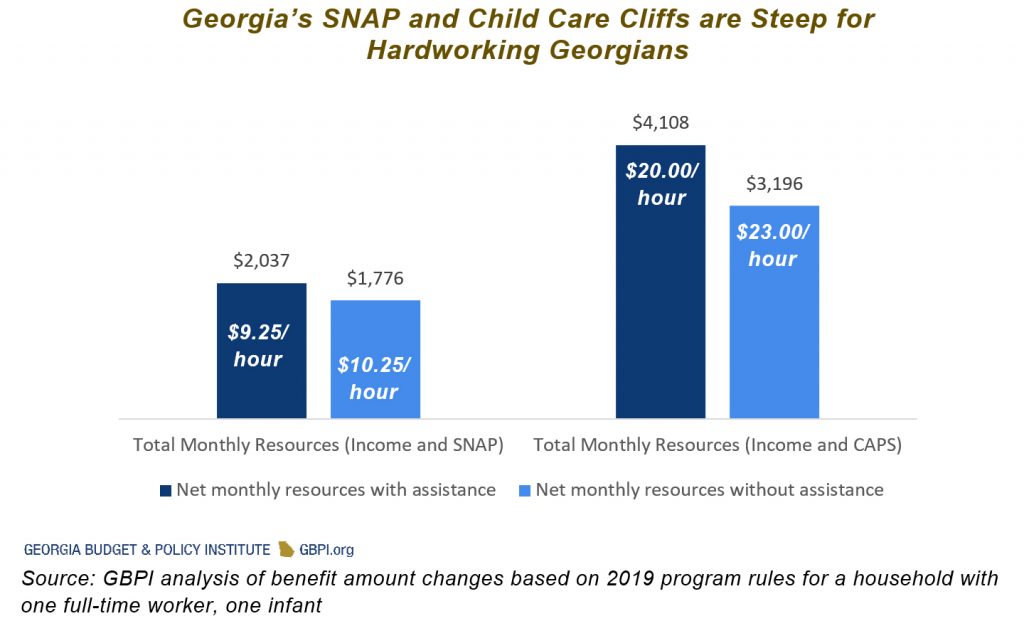

The figure below illustrates the cliff effect when examining two of Georgia’s key safety net programs, SNAP and CAPS, for a single parent using infant care and who works full-time with low wages. Although steadily earning more, due to the steep cliffs, this parent is worse off when she/he experiences a small raise.

Food Assistance (SNAP)

The first major loss of net resources for this Georgia family happens quickly when income increases from $9.25 to $10.25 an hour. The loss of SNAP results in a $261 loss of net monthly resources. The loss in food assistance requires income between $13.25 and $15.25 to cover the loss in resources. While this seems small, SNAP is a proven tool to help individuals and families mitigate food insecurity. The abrupt loss of food assistance is particularly harmful for low-income parents who already cope with little to no supplemental income and makes way for life-threatening health conditions and poorer education outcomes for children and families.[9]

Child Care (CAPS)

The most dramatic effect occurs with child care assistance which is lost when the annual salary tops out at Georgia’s cliff of $42,311 annually for a single parent of one, roughly $21-$22 per hour and 85 percent of Georgia’s federal maximum allowed income limit.[10] This results in an alarming loss of nearly $912 in net monthly resources. Additionally, the loss of child care subsidies curtails opportunities to improve family economic security by forcing low- and moderate-income individuals to foot the full bill of expensive care.

Working Hard Not Good Enough

Several studies argue that the cliff effect reinforces a culture of dependency on the safety net by discouraging work, but there is an abundance of research that suggests unfair rules are much more likely to hurt a parent’s ability to navigate the labor market and find quality, family-supporting work.[11]

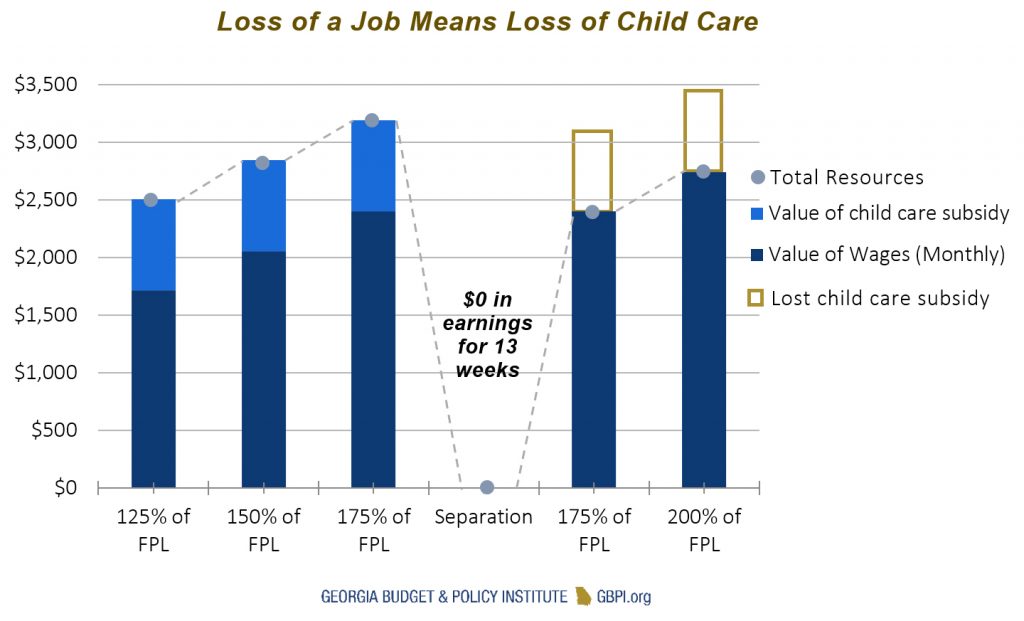

For example, when a parent loses their job or is unable to meet work or education requirements for child care subsidies, they risk losing assistance completely unless they re-enter the workforce or a training program within a short amount of time (13 weeks according to Georgia’s subsidy policy).[12] The figure below shows that even when the parent resumes employment at their previous wage level, they are unable to access care because the rules have changed. They now make slightly more than Georgia’s very low initial income threshold of $24,889.[13]

Georgia requires that parents experiencing separation from employment or training programs report their circumstances immediately. They are then able to remain registered for a maximum of 13 weeks while participating in a state-approved job search. Even though the parent’s case remains open during the job search, the state discontinues payment of the subsidy during this period and the parent is responsible for negotiating payments directly with their provider.[14]

The loss of child care can have a devastating effect on the long-term participation of parents in the workforce with even larger consequences for the state’s future economy. A 2018 report found that 1 in 5 parents have been forced to quit a job, school or work training program, significantly reduce hours, turn down advancement or enrollment opportunities, or even face termination because of child care issues. Major disruptions in care can result in more than $1.75 billion lost annually in economic activity in Georgia.[15]

Fixing Cliff Effects Key for Improving Gender Equity and Child Well-Being

Georgia can help redress inequities by helping families mitigate these cliffs. In Georgia, 366,000 family households living in poverty are headed by single working moms who are particularly in need of food and child care assistance.[16] Considering that women in Georgia earn 70 cents for every dollar men make, coupled with the fact that mothers tend to earn less than women without children, providing access to affordable child care and food assistance is an important gender equity issue. Women of color feel the effects more acutely. Native American and black women in Georgia only make 64 percent of what white men earn in the state. The number decreases to 48 percent for Latina women.[17]

Due to a long history of direct discrimination, racist public policies and ongoing barriers to economic opportunity in Georgia, families of color have long been prevented from building wealth.[18] This has generational consequences for children. Ensuring that low-income children of color have access to affordable child care and food assistance while their parents are working their way up the economic ladder is imperative for achieving racial and ethnic equity. In Georgia, youth of color represent about 60 percent of young children but represent 76 percent of children in households receiving public assistance.[19]

Proposed Solutions

Proposed Solutions

All safety net programs have matching goals: encourage work and education, promote economic security and lift families out of poverty. The programs mentioned in this report have been very successful in helping move families out of poverty when designed well. However, many challenges remain for Georgians receiving public assistance. Below are opportunities for Georgia’s policymakers to make safety net programs work better for those who need them the most.

Streamline safety net program reporting requirements

Public assistance programs integrated into broader eligibility processes help achieve shared goals across programs. This ensures that all families with one form of assistance receive other benefits for which they are eligible. In 2017, Georgia created an award-winning integrated eligibility system, known as Georgia Gateway, to help achieve this. As we seek continuous system improvement we should keep in mind the ways the system can help prevent the cliff effect.

Georgia’s SNAP program requires monthly reports to track income and work changes. Parents enrolled in the CAPS program are responsible for notifying their case manager within 10 days of becoming aware of the change in work or income. A patchwork of reporting requirements can trip families up and lead to punitive sanctions, including the complete loss of assistance. South Carolina, Colorado and Idaho align reporting and redetermination dates for major safety net programs. They also prepopulate forms that require clients to report less information which reduces client burden and saves time for workers who often must reconcile conflicting or missing information on redetermination forms.[20]

SNAP and CAPS have various work and education requirements. To help families avoid the loss of assistance due to administrative hurdles, Georgia should make sure that work requirements and penalties match those of other major programs. For example, SNAP recipients are required to complete 30 hours per week.[21] This is more than the 24 hours a week required for child care assistance.[22] Making sure work rules are consistent across programs will help with some of the confusion parents experience when attempting to accurately report their activities and maintain assistance.

Raise the broad-based categorical eligibility gross income limit from 130 percent to 200 percent of federal poverty line

Georgia is just one of 10 states that has not raised the broad-based eligibility limit above 130 percent of the federal poverty line, or about $21,000 for a family of two, as done by neighbors North Carolina and Florida.[23] Broad-based categorical eligibility (BBCE) is a policy that makes households eligible for SNAP because they receive or are authorized to receive non-cash TANF funded services, including job training. Federal guidelines allow states to extend SNAP eligibility to TANF-funded program participants with incomes as high as 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level. This can help reduce the first major SNAP cliff effect and help families avoid unnecessary hunger.

Help families avoid permanent cliffs by raising the initial income limits for child care subsidies

Raising the state’s initial income limit for CAPS can help parents who lose child care subsidies re-enroll while also promoting continuity of care. If a single parent of one who lost subsidies due to job loss and re-enters the workforce making just over the initial eligibility limit of $24,889 a year, the parent is ineligible for care. Individuals making well above the limit struggle to afford the costs of Georgia’s expensive child care.

Thirty-seven states, including Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and North Carolina, have initial eligibility limits higher than Georgia.[24] Georgia needs initial eligibility criteria that accurately reflects the economic conditions of the state for low-to-middle income families. During GBPI’s people-first statewide listening tours, parents said restrictive income eligibility limits are a persistent barrier. Increasing Georgia’s initial eligibility threshold will help families who earn more than the current limits but less than what it takes to meet their basic needs avoid disruptions in work.

Implement transitional child care for parents who are unable to meet work requirements or exceed income limits

States offer transitional child care subsidies when families experience changes in work or income. For example, Rhode Island continues to pay child care until family incomes reach 225 percent of the federal poverty level.[25] Tennessee offers up to 18 months of additional payments for families who have their cases closed.[26] South Carolina provides up to 24 months of payments for families who exceed the income limits or have disruptions in work.[27]

Transitional child care services funded by the state can provide game-changing benefits to families, especially those who live in areas with difficult labor markets. Georgia’s economy continues to improve overall, but the long tail of the Great Recession still lingers in many counties. This is an important consideration for safety net programs, since states require work or training to maintain assistance.

Extend eligibility for CAPS to 4-year college students

Georgia is one of only 10 states that limits parents receiving state-funded child care subsidies to less than a bachelor’s degree.[28] This rule threatens the future earning potential and financial security of families. There is no shortage of research that demonstrates the link between greater educational attainment, lifetime earnings and multigenerational benefits. By expanding the education criteria to include bachelor’s degrees, thousands of Georgia students who are parents stand to gain. If a parent currently decides to pursue a bachelor’s degree to move up the economic ladder, they become ineligible for child care assistance, leading them to fall off the child care cliff.

Conclusion

Policies that erode wages and reinforce poverty further disadvantage families in Georgia by contributing to the weakened labor market. As parts of the state are still slowly recovering from the recession, we should pursue policies that build up working families by increasing flexibility for safety net programs like food and child care assistance. These families play by the rules and work hard but public policies continue to erect barriers to economic mobility. The role for policymakers should not be to punish Georgians by further restricting safety net programs but to create policies that reward hard work and promote economic mobility for working families.

Evidence shows that parents who receive public assistance like food and child care support experience fewer work disruptions, work more hours, stay employed for longer periods and enjoy higher family earnings. The evidence also shows that safety net programs help children, including infants, gain economic, social and health benefits that extend well into adulthood. In this moment, policymakers have tremendous opportunities to make our safety net work for working people.

Endnotes

[1] National Center for Children in Poverty. http://www.nccp.org/projects/mwsw.html

[2] GBPI analysis of 2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates

[3] GBPI analysis of the 2017 MIT Living Wage Calculator. Data provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Livingwage.mit.edu

[4] “In Georgia, Safety Net Lifts Roughly 1.4 Million People Above Poverty Line and Provides Health Coverage to 43 Percent of Children”. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 2016. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/7-22-16pov-factsheets-ga.pdf

[5] IRS guidelines updated for 2019. Benefit amounts represent one parent, one qualifying child in a household earning less than $40,320 annually. https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions-for-individuals

[6] 2018-2019 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program guidelines. United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. 2018; A “household” for SNAP consists of individuals who live together in the same residence and who purchase and prepare food together https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility

[7] Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) Policy Manual. 2018. Department of Early Care and Learning. https://caps.decal.ga.gov/assets/downloads/CAPS/0-CAPS_Policy-Manual.pdf

[8] GBPI analysis of the 2018 Self-Sufficiency Standard for Georgia. Data provided by the University of Washington. http://www.selfsufficiencystandard.org/the-standard

[9] Cliff Effects and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. 2017. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/communities-and-banking/2017/winter/cliff-effects-and-the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program.aspx

[10] The threshold for ongoing eligibility in the CAPS program is 85% of the state median income (SMI), or $42,311 for a family of 2. SMI is updated by the federal government prior to the beginning of each federal fiscal year (October 1) and is dependent on family unit size. https://caps.decal.ga.gov/assets/downloads/CAPS/AppendixA-CAPS%20Maximum%20Income%20Limits%20by%20Family%20Size.pdf

[11] See Ohio’s Childcare Cliffs, Canyons and Cracks report. 2014. Policy Matters Ohio. https://www.policymattersohio.org/research-policy/quality-ohio/revenue-budget/budget-policy/ohios-childcare-cliffs-canyons-and-cracks; See Falling off the Cliff: Increasing Economic Security for Low Income Adults as the Safety Net Shrinks. 2015. https://www.systemdynamics.org/assets/conferences/2015/proceed/papers/P1389.pdf

[12] Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) Policy Manual. 2018. Department of Early Care and Learning. https://caps.decal.ga.gov/assets/downloads/CAPS/0-CAPS_Policy-Manual.pdf

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] See Opportunities Lost: How Child Care Challenges Affect Georgia’s Workforce and Economy. 2018. Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce and the Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students. http://geears.org/wp-content/uploads/Opportunities-Lost-Report-FINAL.pdf

[16] GBPI analysis of 2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates

[17] See Economic Opportunity Agenda for Georgia Women. 2016. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2016/economic-opportunity-agenda-for-georgia-women/

[18] See Growing Diverse, Thriving Together. 2018. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/2018/growing-diverse-thriving-together/

[19] Data retrieved from Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center. https://www.aecf.org/work/kids-count/

[20] See Changing Policies to Streamline Access to Medicaid, SNAP, and Child Care Assistance. 2016. Urban Institute. http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/78846/2000668-Changing-Policies-to-Streamline-Access-to-Medicaid-SNAP-and-Child-Care-Assistance-Findings-from-the-Work-Support-Strategies-Evaluation.pdf

[21] Georgia Online Directives Information System (ODIS) of the Georgia Department of Human Services (DHS) Food Stamps (SNAP) Section 3380

[22] Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) Policy Manual. 2018. Department of Early Care and Learning. https://caps.decal.ga.gov/assets/downloads/CAPS/0-CAPS_Policy-Manual.pdf

[23] United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2019. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/snap/BBCE.pdf

[24] See Overdue for Investment: State Child Care Assistance Policies. 2018. National Women’s Law Center. https://nwlc-ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NWLC-State-Child-Care-Assistance-Policies-2018.pdf

[25] Rhode Island Department of Human Services. Retrieved February 2019. http://www.dhs.ri.gov/Programs/CCAPProgramInfo.php

[26] Tennessee Department of Human Services. Retrieved February 2019. https://www.tn.gov/humanservices/for-families/child-care-services/more-about-child-care-payment-assistance.html

[27] See South Carolina Voucher Program Policy Manual, Sec. 2.8. 2016. https://dss.sc.gov/media/1488/abc-voucher-2017-v27.pdf

[28] See Overdue for Investment: State Child Care Assistance Policies. 2018. National Women’s Law Center.