Marisol Estrada decided to attend Armstrong State, now part of Georgia Southern University, because it was in her hometown of Savannah and she could save on living expenses. She learned that tuition didn’t increase after 15 credit hours, so she enrolled in at least 18 credit hours each semester. She worked multiple jobs on campus, at restaurants and as a babysitter. She applied to countless scholarships. Her high school teachers even raised money and created a scholarship for her.

Estrada was like many Georgia students who struggle to pay for college. But her costs were even higher. Unlike her peers, she is not eligible for federal student loans, and she pays out-of-state tuition and fees totaling nearly $10,000 per semester.

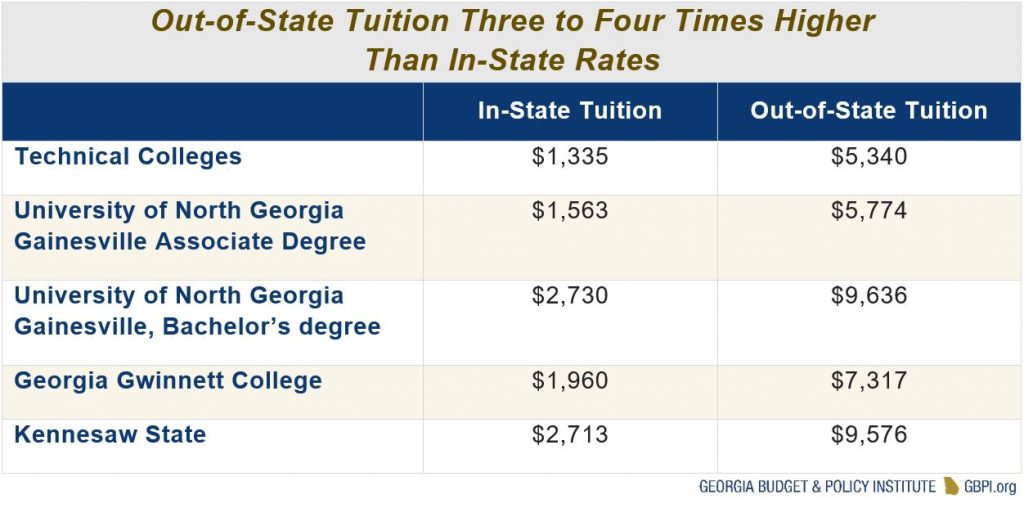

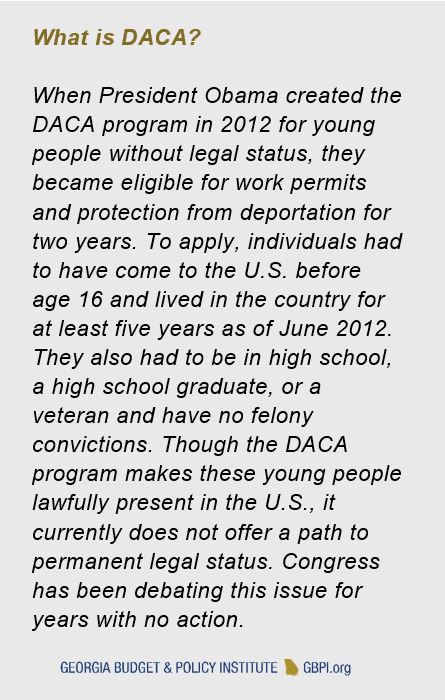

Estrada is one of about 21,600 undocumented young people who participate in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in Georgia. Through DACA, she is lawfully present in the U.S., but Georgia policy requires she pay out-of-state tuition rates three times higher than in-state tuition.

Estrada is one of about 21,600 undocumented young people who participate in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in Georgia. Through DACA, she is lawfully present in the U.S., but Georgia policy requires she pay out-of-state tuition rates three times higher than in-state tuition.

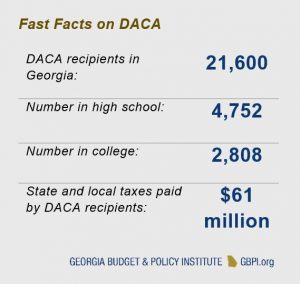

DACA recipients, colloquially known as “Dreamers” or “DACAmented,” have lived in Georgia most of their lives. Twenty-two percent (4,752) are in high school and 13 percent are in college (2,808), according to estimates from the Migration Policy Institute.[1] Georgia has a unique opportunity to include Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program participants in the population eligible for in-state tuition rates. Making college more affordable provides more opportunity for young people who grew up in Georgia, helps the state meet its skilled workforce goals and bolsters the economy by increasing individuals’ earning capacity.

More than 200 years ago, Georgia earned the distinction of being the first state to charter a public university. By supporting higher education, Georgia creates more educated communities that are safer, healthier and more prosperous.

A key asset of public higher education is in-state tuition benefits. The state provides lower tuition rates for Georgians whose taxes help support public colleges and universities. But state policy excludes young people who participate in the DACA program.

A key asset of public higher education is in-state tuition benefits. The state provides lower tuition rates for Georgians whose taxes help support public colleges and universities. But state policy excludes young people who participate in the DACA program.

DACA participants in Georgia pay more than $61 million in state and local taxes.[2] In addition to supporting public higher education, these sales, excise, property and income taxes go to support essential services like public schools, public safety and roads. Estrada says, “At the end of the day we pay taxes, our families pay taxes. We pay into a system…. that puts a lot of obstacles in our way to be successful.”

Though they are part of Georgia communities across the state, Georgia’s DACA program participants face tuition rates nearly three times higher in the university system and four times higher in technical colleges than their friends or teammates may pay. Out-of-state tuition creates a financial barrier compounded by students’ ineligibility for state and federal aid. Program recipients cannot receive Pell Grants, HOPE scholarships or grants or even federal loans.

While Congress has failed to take action on DACA, many states have taken steps to maximize the potential of these young people by opening up opportunities to affordable higher education. Twenty states and the District of Columbia allow students who meet specific residency requirements to pay in-state tuition rates at public colleges, regardless of their immigration status. Sixteen of those states have higher postsecondary attainment rates than Georgia.[3]

Georgia lawmakers can change who qualifies for in-state tuition. For example, legislators proposed expanding in-state tuition to children of active duty military stationed in Georgia, children in Georgia state custody who live with foster families out of state and homeless youth who can’t provide the paperwork to prove their residency. State policy allows schools to grant tuition waivers for many reasons, including excellence in academics, athletics and being a spouse or dependent of a university system, technical college system or public K-12 school employee. Estrada recalls that she went to school with students from Alabama and Florida who received in-state tuition waivers while she, a hometown student, paid out-of-state tuition.

High college costs are an enrollment barrier and put students at higher risk for dropping out.

High college costs are an enrollment barrier and put students at higher risk for dropping out.

- Georgia ranks in the bottom third of states for adults with an associate degree or higher.

- 39 percent of Georgians ages 18 to 24 are enrolled in college.[4]

- 60 percent of full-time first-year students in the university system graduate within six years; rates are lower for low-income students.[5]

- 30 percent of full-time first-year technical college students will complete their credentials.[6]

- The statewide median income for a bachelor’s degree holder is nearly $17,000 more than a person with an associate degree or some college and $22,000 more than a person with a high school diploma only.[7]

National estimates show that DACA recipients enroll in college at the same rates as U.S. adults in the same age group but are less likely to complete.[8] Extending eligibility to in-state tuition rates for these students is a powerful strategy to move more students to and through college and complement the state’s access, affordability and completion goals. It weakens the workforce, stymies human potential and fails to capitalize on investments the state already made in these students through the K-12 school system.

Georgia lawmakers can facilitate a more educated workforce by removing the financial barrier that stands in the way of aspiring college graduates. Despite the large financial obstacles, Estrada was able to graduate from Armstrong, now works as a legal assistant and aspires to go to law school. But she knows how extraordinary that is. She says, “We can’t afford to be mediocre…. If you don’t allow us to be successful and are stopping us from giving back to the state, you’re wasting your resources and your investment in the future of the state.”

[1] Zong, J., et. Al. (2017). A profile of current DACA recipients by education, industry, and occupation. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/profile-current-daca-recipients-education-industry-and-occupation

[2] Hill, M.E., & Wiehe, M. (April 2018). State and local tax contributions of young undocumented immigrants. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/state-local-tax-contributions-of-young-undocumented-immigrants/

[3] GBPI analysis of Census data.

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 American Community Survey, 5-Year Estimates, Table S1401.

[5] University System of Georgia data.

[6] Technical College System of Georgia data. All credentials two years or less, completing within 150 percent of normal time. Figures do not include students enrolling in an associate degree program and leaving after completion of a technical certificate.

[7] U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 American Community Survey, 5-Year Estimates, Table S1401.

[8] Zong, J., et. Al. (2017). A profile of current DACA recipients by education, industry, and occupation. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/profile-current-daca-recipients-education-industry-and-occupation