Services for Georgia’s Vulnerable Get Needed Lift

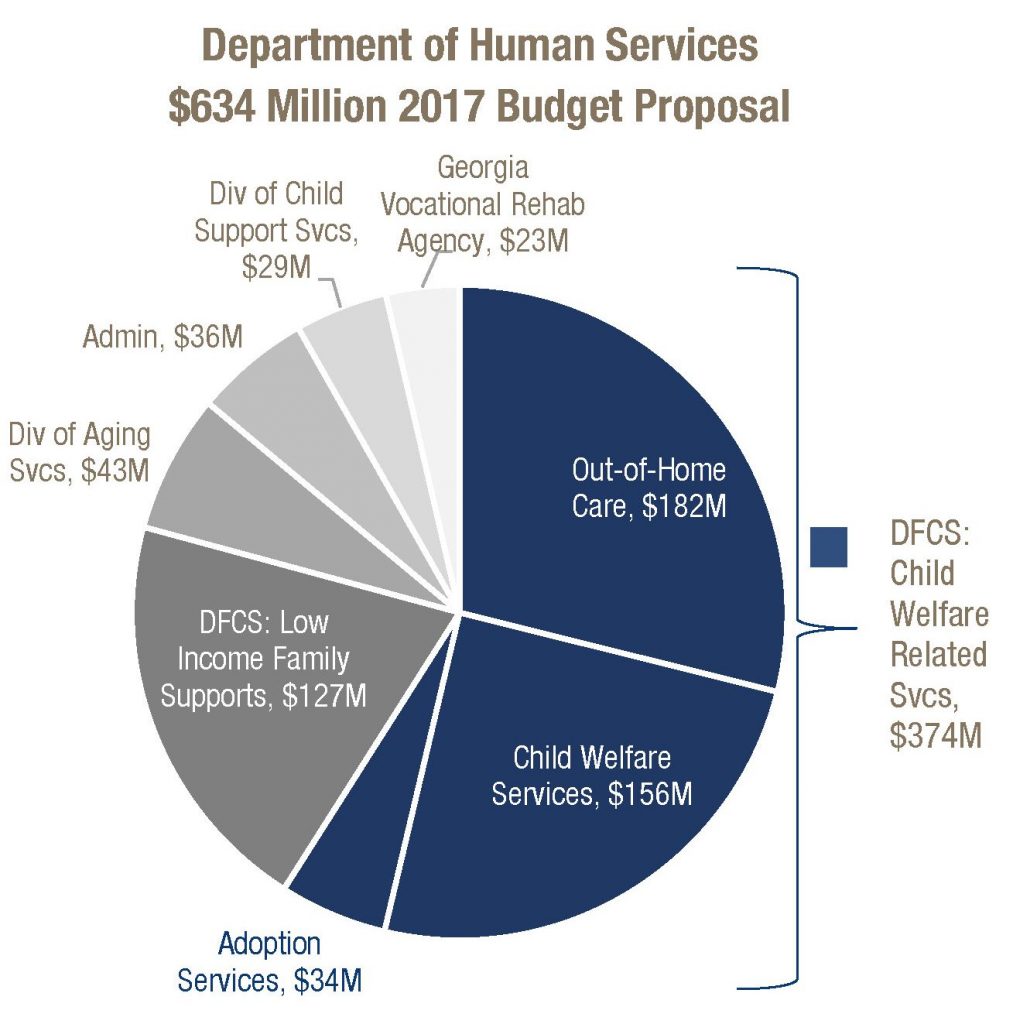

Gov. Nathan Deal’s proposed $634 million Department of Human Services budget for the 2017 fiscal year marks a clear change in direction after years of cuts and public criticism of the agency’s ability to protect and assist Georgia’s most vulnerable children and families. The spending plan adds substantial money for child welfare and other human services, but more is needed to bolster providers and workers as well as care for older Georgians.

State money is distributed in the 2017 budget as shown in the accompanying chart, with the lion’s share going to the Department of Family and Children Services (DFCS).

New in the department’s 2017 budget is:

- $8 million more than 2016 to hire 175 child protective services workers and 10 kinship navigators, who help grandparents and other relatives raising children understand benefits

- $51 million to manage the increasing number of children placed in foster and group homes

- $760,000 more than 2016 to hire 11 more adult protective services workers

Source: Governor’s Budget Report – 2017 Fiscal Year

*Residential Child Care Licensing ($1.6M) and Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention ($1.3M) not shown

Foster Care Gets Sizable Boost, Caregivers Still Stretched

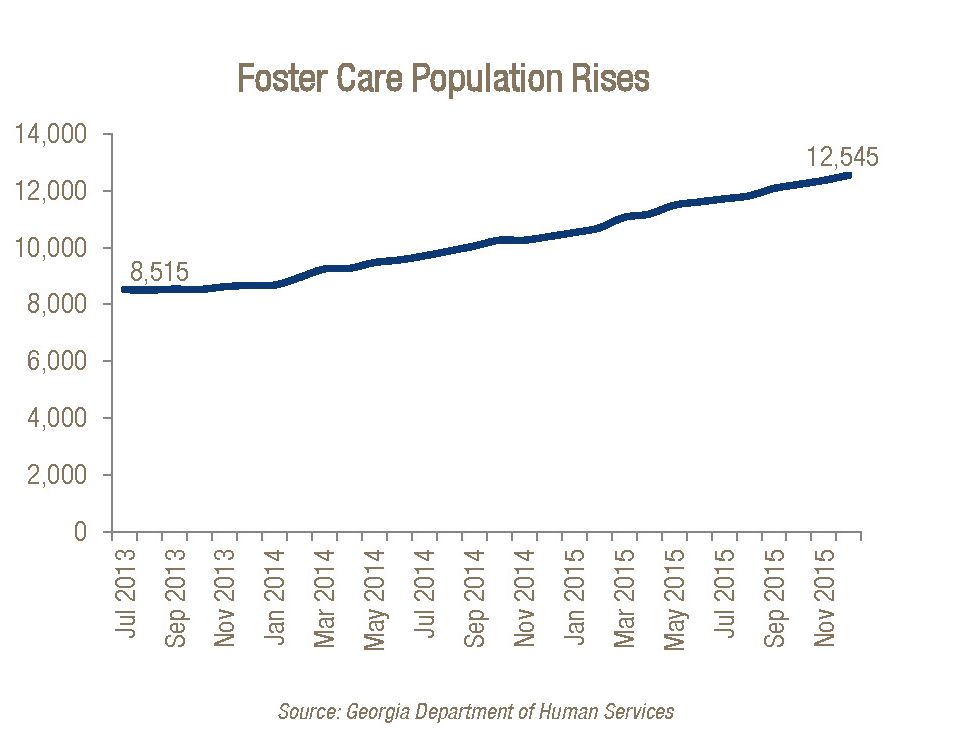

Foster care services account for the largest share of the human services budget and are set to increase in the proposed spending plans. The governor’s budget proposals add $51 million in both the amended 2016 and the proposed 2017 budgets to address growth in foster care. The spending plan also adds state funds in both budgets to replace federal funds.

A new centralized 24-hour toll-free number for suspected child abuse reports contributes to an increased growth in foster care cases. The department phased the hotline in by region in 2013. Child welfare investigations more than doubled from July 2013 to December 2015 and children in foster care increased by 47 percent in that same period. More than 12,000 children were in foster care at the end of December 2015.

| Fund Additions | 2016 Amended Budget | 2017 Budget |

|---|---|---|

| State funds added to support more children in foster care | $51 million | $51 million |

| State funds added to replace federal funds | $34 million | $49 million |

The proposed 2017 budget additions are only enough to pay for increased capacity assuming current rates. Rates paid to foster families, child placement agencies and group homes could still prove inadequate to reimburse families and organizations for the cost of children’s care. A family that cares for a foster child younger than five is paid as little as $15 a day. This is expected to cover food, shelter, clothing, supervision and oversight. Families earning less than $62,010 per year in southern urban areas spend an average of $24 per day to provide for a child younger than five, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Families in rural areas earning similar incomes spend more than $20 per day on average caring for young children.[1]

Low rates for foster families can inhibit caregiver recruitment and retention at a time when more are needed.[2] Some children are now sent to foster care homes several counties away for lack of local foster care families.

Recession-era budget cuts in 2009 and 2010 likely hurt the department’s ability to recruit foster families. The department lost more than 750 case managers from 2008 to 2013, including managers who could have helped recruit and train foster parents.

Group homes and other child care providers also tend to children in foster care. Daily rates for these operations begin at $105 per day. These providers shoulder greater costs than foster homes, including larger staff and insurance expenses. They are increasingly caring for children who require more intense levels of care and must often raise money to cover expenses.

Child Welfare Workers added as Reported Incidents Rise

Spending on child welfare services is set to increase by 10 percent over the prior year in the proposed 2017 budget. This increase is driven in large part by $7.4 million to hire 175 additional child welfare case managers. These managers are often a child’s first line of defense against abuse, abandonment and neglect. The 2017 addition completes the governor’s three-year plan to add 525 child welfare case managers. This initiative increased the division’s budget by $15 million since 2015.

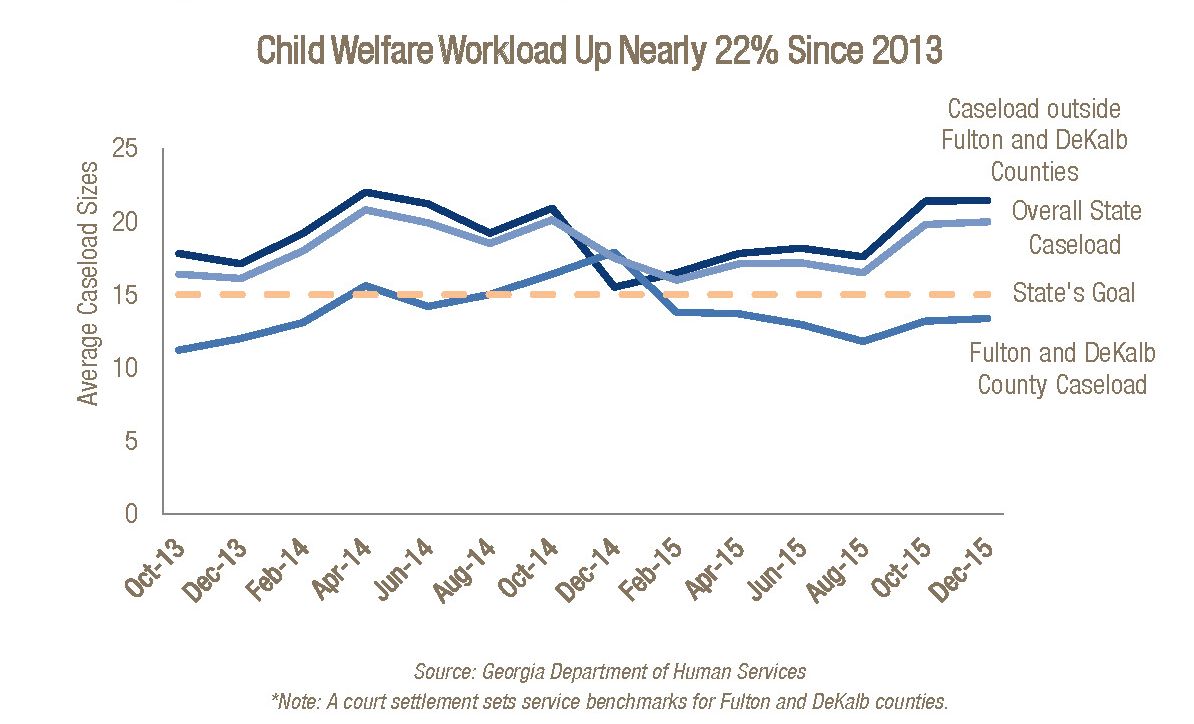

The governor’s goal is to reduce child welfare caseloads to about 15 per cases per worker by 2017. More money could be needed in the 2018 budget to achieve this objective. Each child welfare case manager now handles about 20 cases. The new case managers in the 2017 spending plan are expected to help lower workloads to about 18 cases per worker.

The new centralized toll-free phone number to report suspected child abuse and neglect is adding to the workload, even as new caseworkers are hired. The phone number allows family members or neighbors to report suspected child abuse at all hours. In the past, callers could only report concerns during regular business hours. Each worker handled an average of 20 cases in December 2015, up from 16 in October 2013.

Child welfare case managers are given more to do while earning low salaries. The starting pay is $28,000 for a case manager with a bachelor’s degree. That is less than the annual salary needed to afford a modest standard of living for a one-person household in many Georgia cities including Albany, Gainesville and Valdosta.[3]

Low salaries combined with growing caseloads are a recipe for frequent staff turnover. Among Georgia child welfare case managers, turnover was nearly 39 percent in the 2015 fiscal year. Child welfare agencies should work to limit annual turnover rates at 12 percent or less, according to experts with the Annie E. Casey Foundation.[4]

The 2017 spending plan also adds $584,000 for 10 kinship navigators. This represents less than a quarter of the total navigators recommended by the House of Representatives Study Committee on Grandparents Raising Grandchildren and Kinship Care established in 2015. This committee determined navigators help grandparents and other caregivers work better with the state child services system and access services provided by nonprofits.

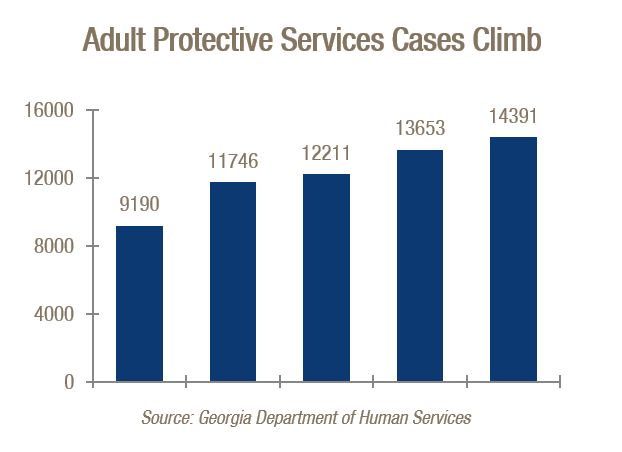

Budget for Older Georgians Increases as Abuse Cases Rise

The population of Georgians age 60 and older is projected to grow by 41 percent by 2030. This aging population will require increased support services. The 2017 spending plan adds $760,000 to hire 11 additional adult protective services workers. This is a final installment in a three-year plan to phase in 33 new workers. The budget also adds nearly $267,000 to support the adult protective services workers added in 2015 and 2016 with technology and travel expenses.

New adult protective services investigations increased 57 percent from 2011 to 2015. This is due in part to 2013 legislation passed to better protect Georgia’s adults that successfully increased awareness and reporting. The state predicts that 965,000 adult Georgians will be the victims of abuse, neglect or exploitation by 2030. This would be an increase of 42 percent since 2010.

The proposed budget also adds $2 million for elderly community living services for 1,000 Georgians. This initiative allows older Georgians to live independent lives in their own communities and to avoid moving to nursing homes. Nursing homes cost the state an average of $17,145 more per year than community-based services. The budget addition is expected to reduce a waiting list of more than 13,000 people asking for assistance with home-delivered meals, transportation, minor home repairs and other services.

The governor’s 2017 spending plan also transfers nearly $47 million from the Department of Human Services to the Department of Community Health to operate the Community Care Service Program. This program uses Medicaid money to provide services to support independent living for older Georgians.

Twelve Area Agencies on Aging help older Georgians and their families access a range of services, including those provided by the community care program. It remains to be seen if these agencies can still act as one stop shops for service access after the department switch.

Reinforcements Coming to Help Low-Income Families

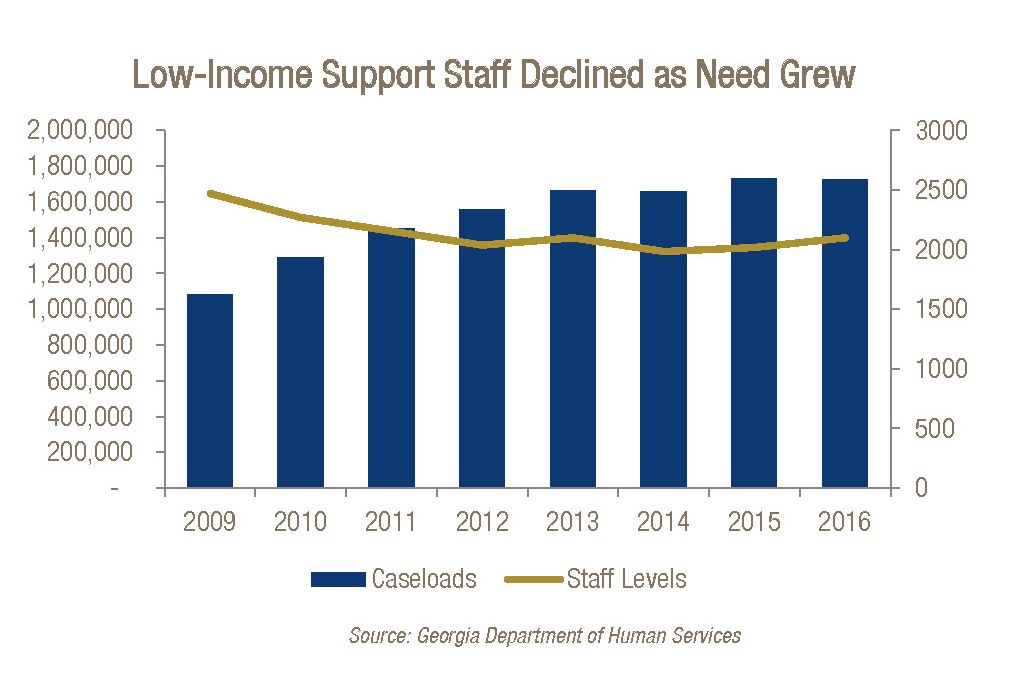

Georgians continue to struggle with poverty and hardship nearly seven years after the Great Recession’s official end. The state’s human services eligibility workers are handling 60 percent more cases than in 2009.

The proposed 2017 spending plan adds $5.4 million to hire 180 workers to help families obtain cash and food assistance, Medicaid and child care. The need for food assistance is growing at a fast rate. About 27 percent more Georgia households received food stamps in in October 2015 than December 2009.

The Georgia Department of Human Services dealt with cuts to eligibility staff made during the recession even as recipients increased. The result was longer wait times for Georgians to receive their food assistance, which in turn put the state in jeopardy of owing as much as $76 million in federal penalties for the delays. While the backlog was cleared, federal scrutiny of the program continues.

Timeliness issues also provoked a lawsuit. A number of Georgians who did not receive their food assistance on time collectively sued the department in early 2014. The department settled in August 2014. Each of the 47,760 households affected is expected to receive an average of $463 in food assistance.

The Division of Family and Children’s Services implemented a One Caseworker, One Family approach in August 2015 to streamline service delivery. This change ensures families are assigned one worker who can help them with a range of services. The new model helped boost the share of families receiving timely benefits to 94 percent from 66 percent. Additional workers can help the division sustain this improvement and avoid federal penalties.

[1]“Expenditures on Children by Families, 2013,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, August 2014.

[2] Hitting the MARC: Establishing Foster Care Minimum Adequate Rates for Children, by Children’s Rights, National Foster Parent Association, University of Maryland School of Social Work, October 2007

[3] Family Budget Calculator, Economic Policy Institute, http://www.epi.org/resources/budget/ .

[4] “A Child Welfare Leader’s Desk Guide to Building a High-Performing Agency: 10 Practices Part One,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2015.