Services for Children and Older Adults Get Substantial Boost

Gov. Nathan Deal’s proposed $732 million Department of Human Services 2018 budget takes another significant step forward to restoring and fortifying the agency after recession-era cuts. The spending plan adds substantial money for child welfare and other human services. Still, more money is needed to ensure equal pay for all foster families.

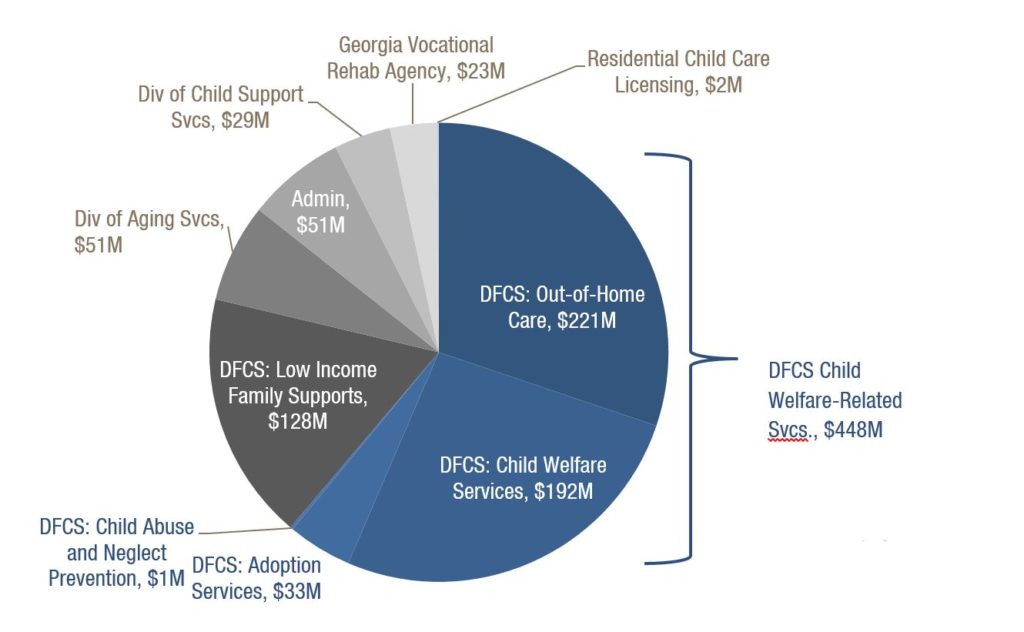

State money is distributed in the 2018 human services budget as shown in the accompanying chart, with the lion’s share going to the Division of Family and Children’s Services (DFCS).

Department of Human Services $732 Million 2018 Budget Proposal

Notable increases to the department’s 2018 budget include:

- $31 million for an increase in the number of children who need foster care

- $26 million to increase the salaries of child welfare workers by 19 percent

- $11 million for a new Integrated Eligibility System

- $4.2 million for new senior services, including Meals on Wheels

Foster Care Budget Rises to Meet Growing Need

Foster care services account for the largest share of the human services budget and are set to expand in the proposed spending plans. The governor’s budget proposals add $29 million in the amended 2017 budget and $31 million in the 2018 proposal to keep pace with growth in foster care.

A centralized 24-hour toll-free number for suspected child abuse reports is a primary reason for the growth in foster care cases. The department phased the hotline in by region in 2013. The department now receives more than 148,000 reports of abuse and neglect per year, a 93 percent increase from nearly 77,000 reports in 2013.[1]

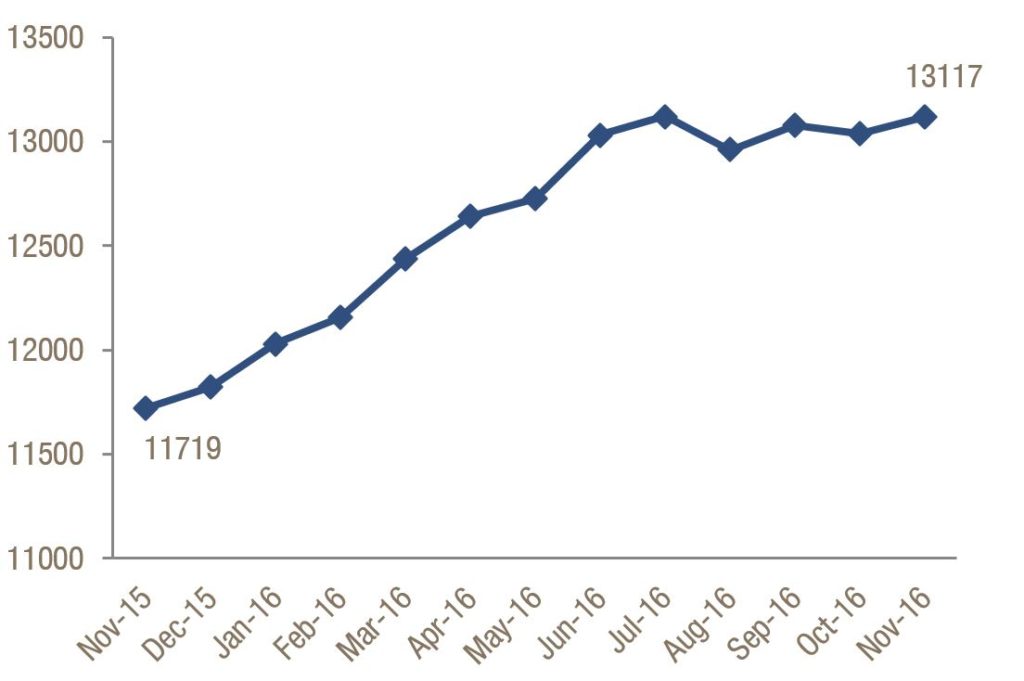

Foster Care Population Rises

Children in DFCS Custody Under the Age of 18

The proposed 2018 budget also includes nearly $4 million to increase monthly payments for children’s care costs to about half of Georgia’s foster families. The foster families projected to receive the increase are recruited and managed by the Division of Family and Children’s Services, as opposed to private agencies. More than 13,000 Georgia children were in foster care at the end of November 2016.

A family that cared for a foster child younger than five in 2016 was paid a little more than $15 a day. This is designed to cover food, shelter, clothing, supervision and oversight. The new money in the budget aims to increase the rates paid to foster parents by 57 percent to about $24 a day for a child younger than five. If approved, the rates paid to foster families will likely be closer in line with what low- and middle-income families spend to raise their children. Families that earn less than $59,200 per year in southern urban areas spend an average of $22 per day to provide for a child younger than five. Families that earn between $59,200 and $107,400 spend about $30 a day on young children, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.[2]

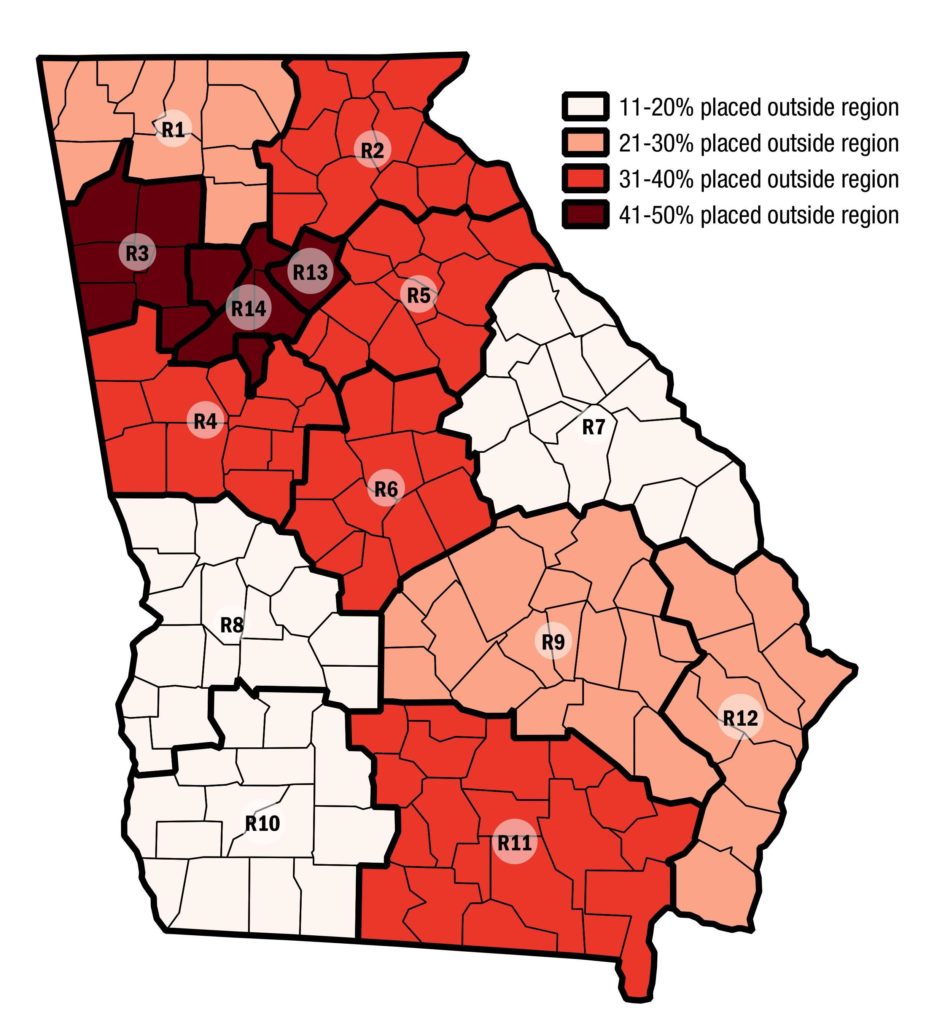

Increased rates for foster families should encourage caregiver recruitment and retention at a time when more are needed. In most Georgia counties at least one in five children are sent to foster care homes several counties away for lack of local placement options.

Still, the increase in payment rates will only benefit the half of Georgia’s foster families recruited and managed by the Division of Family and Children’s Services. Foster families recruited and managed by private agencies are not scheduled for an increase, creating inequity between different groups of families who are both charged with bringing neglected or abused children into their homes.

Children Placed Far From Home Due to Shortage of Local Foster Families

Share of Children Placed Outside of Region

The governor’s proposed 2018 budget also includes $2.9 million to hire 80 new foster care support workers. These new hires are intended to help restore support to foster families that fell off due to the recession. The department lost more than 750 child welfare case managers from 2008 to 2013, including managers who helped recruit, train and support foster parents.

Child Welfare Workers Receive Needed Investment

State spending on child welfare services is set to increase by 21 percent in the proposed 2018 budget compared to the prior year. A $26 million budget increase is intended to boost salaries for child welfare case managers and their supervisors by 19 percent on average. The governor’s 2015 Child Welfare Reform Council report recommended pay increases for case managers.

Case workers are often a child’s first line of defense against abuse, abandonment and neglect. The starting pay for a case manager with a bachelor’s degree is $28,000. That is less than the annual salary needed to afford a modest standard of living for a one-person household in many Georgia cities, including Albany, Gainesville and Valdosta.[3] The proposed raise in the governor’s budget would increase starting salaries up to $35,000. Low starting salaries for Georgia child welfare case managers leaves them far behind counterparts in the Southeast.

Entry-Level Salaries for Georgia Child Welfare Workers Among Lowest in the Southeast

| Regional Rank | State | Entry-Level Salary |

| 1 | South Carolina | $31,805 |

| 2 | Alabama | $31,488 |

| 3 | Tennessee | $31,320 |

| 4 | Mississippi | $30,050 |

| 5 | Georgia | $28,005 |

| 6 | Louisiana | $25,860 |

Source: Georgia Department of Human Services

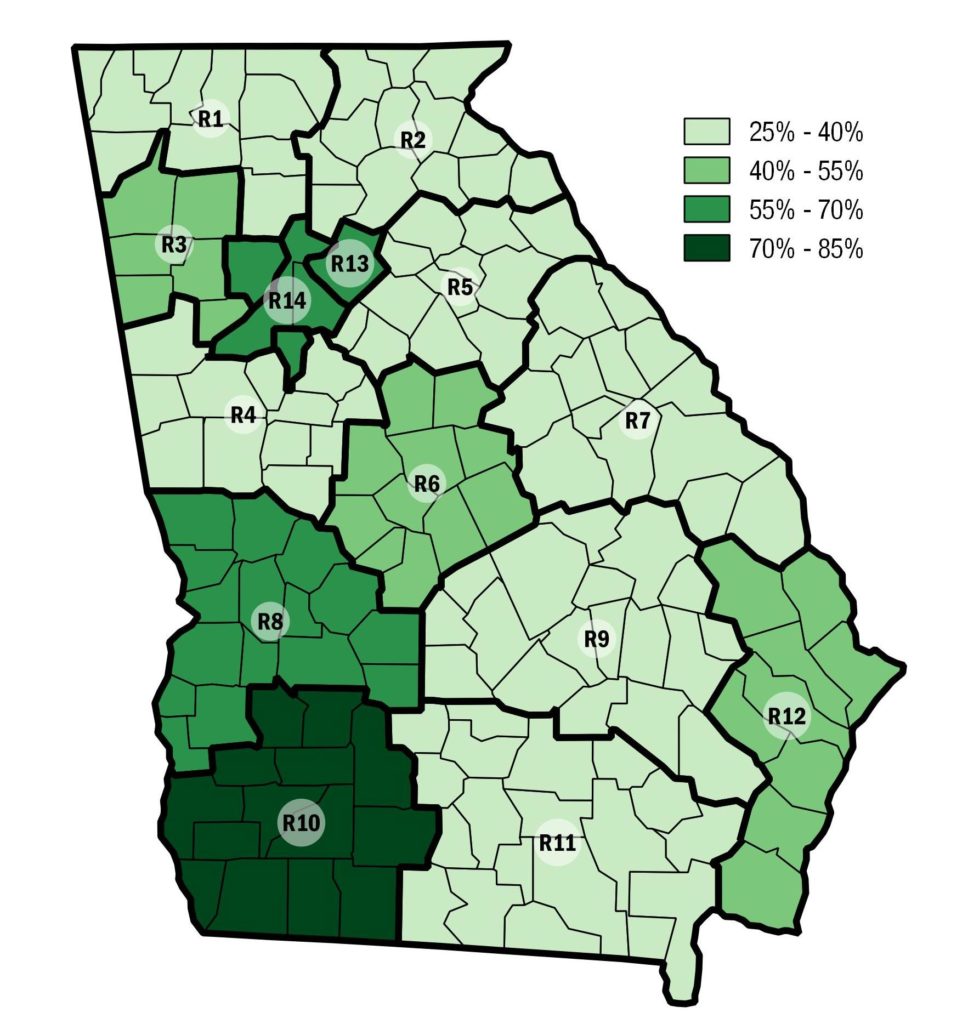

Low salaries combined with growing caseloads are a recipe for frequent staff turnover. The turnover rate for Georgia child welfare workers stands at 32 percent. Child welfare agencies should work to limit annual turnover rates to 12 percent or less, according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation.[4]

Reducing turnover among child welfare case managers helps reduce caseloads for each worker. Each child welfare case manager handled anywhere from 20 to 31 cases at once in 2016, with variation by region. Child welfare experts indicate caseloads should be about 10 to 15 cases per worker. The Division of Family and Children’s services projects caseloads to fall to between 8 and 19 per worker with improved case manager retention.

Reducing Turnover Projected to Reduce Caseloads for Child Welfare Workers

Projected Average Caseload Reduction if All Positions Filled

The proposed 2018 spending plan also adds $2.5 million to hire 27 workers to fully implement a supervisor-mentor program for child welfare workers. Implementing such a program was another key recommendation of the governor’s Child Welfare Reform Council. Mentors who provide intense, one-on-one support to selected supervisors of child welfare workers offer another important strategy to reduce child welfare worker turnover.

The governor’s 2018 budget also includes $2.5 million to hire 25 new human resources employees to meet the department’s recruitment demands. One human resources worker is now available to support an average of 150 employees who deliver services in the Department of Human Services. Experts say the optimal ratio in large organizations is about one human resource worker to every 100 service delivery employees. The department projects the new human resources staff contemplated in the governor’s proposed budget will reduce the ratio to a fraction above that target.

The department added more than 600 child welfare worker positions over the past three years, new employees who require human resource support. The department will also need new human resource support for the new mentors and foster care support service workers proposed in the governor’s 2018 budget.

New Integrated Eligibility System Offers Increased Efficiency, Reduced Fraud Risk

The proposed 2018 spending plan adds $11 million to complete implementation of an Integrated Eligibility System – Georgia Gateway. Georgia Gateway is the largest information technology project in the state’s history. The system is designed to serve as a one-stop shop to allow Georgians to determine eligibility for six of the state’s major benefit programs:

- Medical Assistance, including PeachCare for Kids

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

- Women, Infants, and Children Supplemental Nutrition Program

- Childcare and Parent Services Program

- Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program

Georgia Gateway replaces several older, antiquated systems used to determine eligibility. The new system is designed to offer timely and more accurately delivery of assistance for residents across programs. The department received federal scrutiny over delays in processing benefits from 2014 to 2016. Federal officials warned Georgia it faced $76 million in federal penalties for the delays until lifting the threat in December 2016.

The new integrated system is also designed to reduce the risk of fraud, increase efficiency and lessen manual work. Federal funding covers the bulk of the Georgia Gateway system.

A pilot of the new system is set to begin this winter in Henry County. All of the state’s PeachCare for Kids accounts are set to be migrated to Georgia Gateway at the same time. Following a 90-day pilot, the department plans to phase in the state’s remaining counties in spring and summer 2017.

Spending for Older Georgians Grows to Shorten Long Waiting Lists

Georgians 65 and older are the fastest-growing age group in the state’s population.[5] Anticipating this aging population will require increased support services, the governor’s proposed budget also adds $4.2 million for elderly community living services for 1,000 Georgians. This initiative allows older Georgians to live independent lives in their own communities and to avoid moving to nursing homes. Nursing homes cost the state an average of $18,544 more per year than community-based services.[6] The budget addition is designed to reduce a waiting list of about 9,000 people asking for assistance with home-delivered meals, transportation, minor home repairs and other services.

The governor’s spending plan also adds $750,000 more for home-delivered and congregate meal services. The new money is targeted to reduce the average wait time for seniors seeking home-delivered meals in Georgia. The wait time for an older Georgian to join the meal-delivery program is more than one year. More than 4,000 people are on waiting lists. Meanwhile, nearly 18 percent of seniors in the state face the threat of hunger, giving Georgia the ninth highest share of older adults at risk.[7]

366 Days:

Average Wait Time to Join Home-Delivered Meals Program

Source: Georgia Department of Human Services

This cash infusion is also timely following the state’s first-ever Senior Hunger Summit in 2016. The summit brought together experts, policymakers, and community supporters to discuss the problem of senior hunger in Georgia. The Department of Human Services also created a Senior Hunger Workgroup in 2016. The group is working to develop a state plan by 2018 to lessen senior hunger.

The governor’s 2018 spending plan also includes $766,000 to hire 11 new adult protective services supervisors. The department hired 33 adult protective services workers in the budget years from 2015 to 2017 to help investigate and prevent increased abuse, neglect and exploitation of Georgians 65 or older not in long-term care.

[1] Compares Child Abuse and Neglect Reports for most recent year according to 2017-2018 DHS Budget Presentation to total child abuse and neglect reports for federal fiscal year 2013 as reported in “Child Welfare: Outcome Measures and Results,” Department of Human Services January 2014.

[2]“Expenditures on Children by Families, 2015,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, January 2017. Expenses are from families in southern urban areas.

[3] Family Budget Calculator, Economic Policy Institute, http://www.epi.org/resources/budget/.

[4] “A Child Welfare Leader’s Desk Guide to Building a High-Performing Agency: 10 Practices Part One,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2015.

[5] Author’s analysis of US Census Bureau American Community Survey Table S0101, 2005 – 2015 1 yr. estimates.

[6] Difference between average annual cost of non-Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services and state portion of Medicaid nursing home bed. “Funding for Home and Community-Based Services” Fact Sheet for 2017 Legislative Session, Georgia Council on Aging and Coalition of Advocates for Georgia’s Elderly (CO-AGE).

[7] “Percent of Seniors Facing the Threat of Hunger by State – 2014” National Foundation to End Senior Hunger, June 2016.