To expand Georgia’s economy, the state should reassess the way it allocates resources. For the last few years, Georgia cut state spending on supports for low-income families and increasingly relied on other sources to provide services – which potentially reduced the total services available to these families, as new data shows. To give low-income families in Georgia the chance to secure better jobs and contribute more to Georgia’s economy, the state should invest more in job training, child care, transportation and other work supports.

To expand Georgia’s economy, the state should reassess the way it allocates resources. For the last few years, Georgia cut state spending on supports for low-income families and increasingly relied on other sources to provide services – which potentially reduced the total services available to these families, as new data shows. To give low-income families in Georgia the chance to secure better jobs and contribute more to Georgia’s economy, the state should invest more in job training, child care, transportation and other work supports.

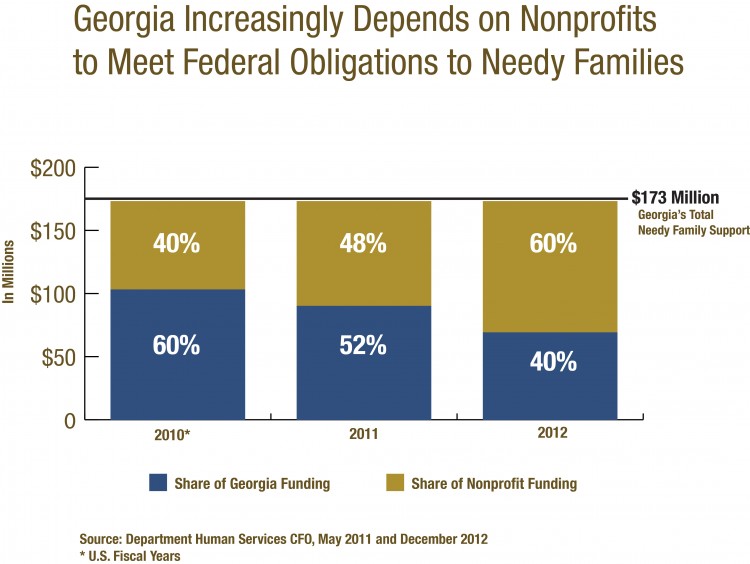

States receive federal funds through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program to help low-income families become financially independent through job preparation, temporary cash assistance and other support. To receive this money, the state must show the federal government it is also contributing resources to serve these low-income families, referred to as Maintenance of Effort (MOE). Georgia is required to show it provides $173 million worth of services to these families.

There are two ways for the state to document services supplied to low-income families: Georgia can count state or local government funds for the services, or it can count spending by third parties on services that they may already provide (third-party MOE). In either case, the services must be delivered to eligible low-income families with children and satisfy four broad purposes – offering cash assistance; promoting job preparation, work and marriage; preventing out-of-wedlock pregnancy and encouraging two-parent families.

Georgia’s Shift of TANF Obligations to Nonprofits is Flagged by Congress

Prompted by members of the U.S. Congress, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) performed a study of these third-party services, which revealed two primary concerns. (Our analyst commented on this study in November).

The GAO study’s first concern is that the practice of counting third-party services “may reduce the overall level of services available to low-income families in a state if, for example, that state counts services already provided by third parties while reducing its own spending.”

Georgia may be doing just that: counting services that are already provided by numerous private nonprofits to meet federal obligations, while reducing its own spending on the programs. For example, during the last federal fiscal year, Georgia counted $104 million, or 60 percent, of third-party spending toward its required efforts under TANF. Georgia also spent about $3.4 million less for work assistance programs and $500,000 less for technical education for TANF-eligible families, compared to federal fiscal year 2010.

Second, the study says counting services delivered by third parties toward a state’s required efforts under TANF is a concern because the practice may “not be in keeping with the intent” of such requirements. Though the practice of counting third-party services is allowable by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the practice is not mentioned in the federal law creating TANF. In fact, the practice of counting third party services first surfaced in a 2004 policy announcement by the department, eight years after the law took effect.

State officials are aware their practice of counting third-party services toward federal requirements is under scrutiny. Lynn Vellinga, CFO for the Georgia Department of Human Services, said at a 2012 department board meeting:

“…there is a policy debate going on with TANF reauthorization at the federal level about whether states’ ability to use third-party funds to meet TANF MOE should be restricted or eliminated. If federal TANF law changes under reauthorization, we obviously will have to reassess our practices to remain in conformance with federal law.”

The concern at the federal level regarding counting third party services is understandable, considering the consequences for Georgia’s families and the state’s economy. Limiting services to Georgia’s low-income families, who could become financially independent with child care assistance, job training and other support, will keep the state’s economy from reaching its full potential. About 349,000 families in Georgia, or 14.7 percent, live below the poverty line. (The poverty line was $22,891 for a family of four in 2011, the most recent year available). If Georgia is serious about expanding the state’s economy, it should increase its investment in its low-income families.