As the country finds itself in another historic recession, Georgia faces an opportunity to focus state financial aid resources on an equitable economic recovery. A budget-neutral and effective option is to rework the state’s troubled lottery-funded Student Access Loan program to fund scholarships and grants that support degree completion.

Georgia is the only state that uses state appropriations to fund a student loan program. Policymakers created Student Access Loans in the wake of the last recession. Since then, average tuition, fees and student loan debt have soared. Thousands of students drop out each year, some within the final year of their programs, due to unexpected expenses that can derail the ability to pay tuition and fees. Many students take on debt and struggle to pay back loans due to circumstances outside their control, like a weak job market or lack of family savings and wealth.

After the bottom of the last recession, 99 percent of new jobs went to those with at least some college education.[1] The Great Recession sped up long-term trends that provide vastly different opportunities to those with a college degree and those without. At the same time, excessive student loan debt has been linked with lower rates of homeownership and small business formation, two key drivers of the economy.[2], [3] Georgia’s workforce will be stronger in a post-pandemic recovery if more Georgians have postsecondary credentials without the excessive student debt burden that drags down the economy.

Lottery-Funded Student Access Loans Unique to Georgia

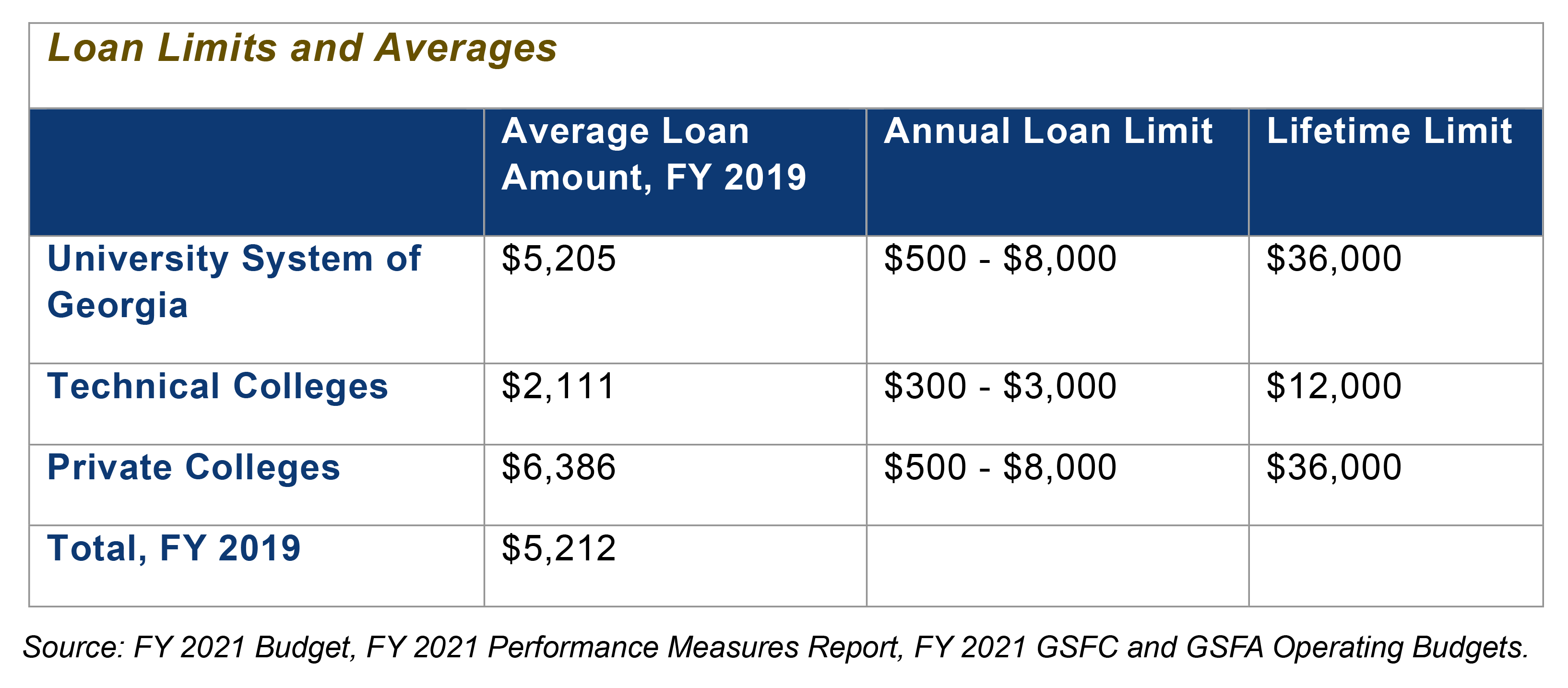

Georgia began lending lottery funds to students through Student Access Loans (SAL), or Low-Interest Loans, in 2012. These loans carry a one-percent interest rate. Student borrowers must first use all available federal, institutional and private scholarships, loans and veterans’ educational benefits. Students can use SAL at most public and private colleges and universities in Georgia, including technical colleges.[4]

Georgia is the only state with a loan program that relies on state appropriations. Other states use proceeds from the sale of bonds, loan repayments and investment income to fund state student loans. Since SAL’s inception, the state has loaned nearly $234 million in lottery funds to Georgia students through it.[5]

Most students using SAL come from families with low incomes; 73 percent of students were receiving Pell Grants, a federal grant for students with financial need.[6] State rules give current HOPE and Zell Miller Scholars and prior year SAL recipients priority for SAL. Thirty percent of SAL borrowers also received HOPE or Zell Miller Scholarships in 2019; an additional 4 percent also received HOPE or Zell Miller Grants.

Few Student Borrowers Get Student Access Loan Debt Relief

Student loan debt relief is sometimes referred to as loan “forgiveness,” “cancellation,” “cancellation credit,” “discharge” or “conversion to grant.” All terms refer to financial aid that needed to be paid back and no longer needs to be repaid.

The state administers several debt relief options through multiple state agencies. Lawmakers create these benefits as incentives for desired behaviors, like pursuing occupations with perceived shortages, such as medicine or engineering. But relief often reaches few students and certifying eligibility is complicated. The Georgia Student Finance Authority (GSFA) administers the following debt relief options related to the $26 million SAL appropriation:

- Public service and Science, Technology Engineering or Math (STEM) teacher loan cancellation. Since this debt relief option began in 2012, 140 total student borrowers have benefitted from partial loan cancellation. In 2020, GSFA received 159 applications for STEM/Public Service Loan cancellation.[7] A 2017 audit report found that the state’s public service loan forgiveness does not target high-need occupations or geographies and is unlikely to recruit or retain persons in specific occupations or locations.[8]

- Temporary Student Access Loan for Zell Miller Scholars due to COVID-19. High school students with the 3.7 GPA required for the Zell Miller Scholarship who could not take the SAT or ACT due to test cancellations can apply for SAL. These small loans will fill the gap between HOPE award amounts, which students will receive, and the Zell Miller award. Home study students can receive loans for the Zell Miller amount. The state will change the loan to a grant or cancel the loan after students submit qualifying SAT or ACT scores. The deadline for submitting SAT/ACT scores is currently June 30, 2021 (visit gafutures.org for updates).

- Technical college students graduating with a cumulative 3.5 GPA or higher can have loans discharged in full. Since this option began in 2015, 1,381 students have qualified for loan discharge.[9]

Many Student Borrowers Struggle to Repay Student Access Loans

Though student loans enable many students to go to college, the negative effects of debt loom large for many Georgians. Excessive debt creates obstacles to wealth creation, including lower homeownership rates among young adults.[10] Student loan debt is also linked to a decrease in small business formation. Small businesses are the most reliant on personal debt for financing, and counties with the largest growth in student debt experienced the smallest net growth of small businesses.[11] Student debt also contributes to the racial wealth gap, which grows during the early adult years.[12]

Student loan debt is common. Most college students who graduate finish their degrees with debt: 57 percent of Georgia college graduates carry student loan debt and that debt averages $28,824.[13] Many more students have debt, but no degree.[14]

The racial wealth gap both contributes to and is exacerbated by student debt. Due to historic policies and practices that excluded African Americans from wealth-building, like redlining and discriminatory lending, the median net worth of Black households in Georgia ($21,000) is much lower than the median net worth for white households ($124,000).[15] With fewer resources to pay for college, Black students are more likely to turn to federal loans to finance higher education, and they borrow more on average.[16] National data show debt divides grow even larger after graduation, as some students pursue graduate school or face a job market that prioritizes white graduates.[17]

Many student borrowers struggle to pay back their loans, and SAL borrowers default at higher rates. About three in 10 SAL borrowers who entered loan repayment in 2017 defaulted on their loan within three years. This is three times higher than the federal loan default rate (default is failing to make payments on a loan for more than 270 days). [18], [19]

Sometimes administrative barriers hinder repayment, rather than borrowers’ inability to pay. For example:

Kendall, a first-generation college student from Marion County, applied for a Student Access Loan after she hit federal loan limits. In addition to a scholarship from Agnes Scott College, she received the federal need-based Pell Grant and state HOPE Scholarship, yet she still faced a financial gap. SAL helped her pay for college, but the problems began as soon as she owed her first payment for the interest accumulated on the loan while she was in school. “The bill was $15. I could not pay that $15. And the reason I could not pay is because there was no way to get the money to them,” she says. Kendall experienced multiple problems with the website and online payment system, days of unanswered phone calls and a state agency website that displayed only a generic office address. Missing that initial payment led to an increase in her interest rate. She says, “To this day, the only way I can pay is to mail a check, hope that it gets there and that nobody loses my check.” Now working as a teacher, Kendall continues to successfully make payments on her much-larger federal loan but almost gave up trying to repay SAL. “I’ve never missed a payment on the other loan. [Problems repaying SAL] are not because it’s a financial burden, it’s an administrative hassle.”

Even the existing student loan relief options may not be reaching borrowers because of administrative barriers:

Emily graduated in four years at the top of her class from Armstrong State University. She put herself through college but did not qualify for Pell Grants and maxed out on federal loans. She took out a Student Access Loan to cover expenses. After graduation, Emily made regular payments and thought she was doing everything right. She started working at a non-profit organization in Savannah focused on homelessness, and a Georgia Student Finance Authority representative told her that working there for one year would qualify her for partial loan cancellation. After a year, the agency denied her application. After multiple conflicting conversations, GSFA told Emily she had to work for a state agency to qualify. She also discovered that, without her knowledge, the interest rate had jumped from 1 to 8 percent because she had not submitted a form confirming her graduation. And an administrative error meant the agency withdrew three payments in one month from her bank account. Emily now works for a county health department in Arizona. She decided to refinance her loans with a different provider to get a better interest rate and for a better customer service experience. “[SAL] ended up being more hassle than it was worth,” she says. “I would warn people about using it.”

Online reviews and complaints filed with the Better Business Bureau indicate that Kendall and Emily’s stories are not unique. Problems with repayment can lead to loan default, which has serious consequences, including damage to credit scores, wage garnishment and ineligibility for programs like HOPE or even the recent Paycheck Protection Program meant to keep people employed during the pandemic. Debt can continue generational cycles of financial insecurity.

Loans More Expensive to Administer than Scholarships and Grants

Georgia Student Finance Authority (GSFA) administers Student Access Loans and state-general-funded scholarships, like the Tuition Equalization Grant for students who attend private colleges or universities, REACH Georgia and a variety of other small, specialized scholarships. Georgia Student Finance Commission (GSFC) administers HOPE and Dual Enrollment.

Administrative costs for GSFA are much higher than for GSFC, relative to the value of scholarships, grants and loans they manage. The state spends $10 for every $1,000 awarded in HOPE or Dual Enrollment. In contrast, the state spends $83 for every $1,000 awarded in SAL or a state-general-funded scholarship or grant.

Loan programs generally require more administration than scholarships or grants. Though the state collects money from borrowers in the form of interest and fees, it also incurs losses through default (affecting 31 percent of SAL borrowers within three years of entering repayment) and costs from disbursement, application processing, collections and answering borrower questions.

Policy Recommendations for State Student Loan Debt Relief

Policymakers created Student Access Loans amid major changes to HOPE in 2011 as a “loan of last resort” for students. Since then, lawmakers have appropriated $26 million per year for SAL. It is the only state-funded loan program in the country. Instead of adding to students’ existing debt burdens—and the state’s administrative burden for servicing loans —a budget-neutral, efficient and effective option to use lottery funds and boost economic recovery is to award scholarships or grants focused on degree completion.

Convert $26 million in Student Access Loans to need-based scholarships or emergency grants for students near graduation.

Georgia is one of two states without need-based scholarships and the only state that uses state appropriations for student loans. The state already targets the most financial aid to students from middle- and upper-income families; it should target additional scholarship dollars to students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.[20] Four-year and technical colleges have already tested one popular option, called the “last mile” or “emergency grant” approach, which uses small dollar amounts to stop students near graduation from dropping out due to financial challenges. SAL dollars could scale and supplement this innovative and successful approach by creating a need-based scholarship for students close to completing their degree, certificate or diploma.

Expand Student Access Loan debt relief.

After repurposing SAL to a scholarship, the state should forgive outstanding SAL debt. Current relief options benefit few borrowers, and the program suffers high default rates—unsurprising given one of the eligibility requirements is maximizing all available loan and scholarship options and reported administrative problems for borrowers in repayment. Debt burden hurts individuals’ and ultimately communities’ economic strength.

If the last economic recovery is a guide, the vast majority of new jobs will go to those with some college education.[21] Evidence also suggests that student loan debts hurt economic activity like homeownership and small business formation.[22], [23] The state’s economy and workforce will be stronger if more hardworking Georgians complete their degrees and credentials without excessive debt burden that drags down the economy. We can leverage all of Georgia’s talent by knocking down small financial barriers to student success.

Appendix

For more information, visit www.gafutures.com.

Costs to Student Borrowers

- Loan origination fee: 5 percent of loan amount, not to exceed $50

- Interest rate: 1 percent; increases to 5 percent after borrower defaults or fails to make payments for 270 days

- Late fees: 6 percent of the monthly payment

- Monthly “Keep In Touch” payments are ten dollars per month and due starting 60 days after loan disbursement.

Endnotes

[1] Carnevale, A., Jayasundra, T., & Gulish, A. (2016). America’s divided recovery: College haves and have nots. Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/americas-divided-recovery/

[2] Mezza, A., Ringo, D., & Sommer, K. (2019 Feb). Can student loan debt explain low homeownership rates for young adults? Consumer & Community Context. Federal Reserve Board Division of Research and Statistics. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-january-consumer-community-context.htm

[3] Ambrose, B. W., Cordell, L., & Ma, Shuwei. (2015 July). The impact of student loan debt on small business formation. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

[4] For more information, visit www.gafutures.org/hope-state-aid-programs/loans/

[5] Georgia Student Finance Commission data.

[6] Georgia Student Finance Commission data.

[7] Georgia Student Finance Commission.

[8] Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (Oct. 2017). Loan forgiveness programs: Ongoing assessment of loan forgiveness programs could enhance effectiveness.

[9] Georgia Student Finance Commission.

[10] Mezza, A., Ringo, D., & Sommer, K. (2019 Feb.). Can student loan debt explain low homeownership rates for young adults? Consumer & Community Context. Federal Reserve Board Division of Research and Statistics. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-january-consumer-community-context.htm

[11] Ambrose, B.W., Cordell, L., & Ma, Shuwei. (2015 July). The impact of student loan debt on small business formation. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

[12] Houle, J.N., & Addo, F. (2018). Racial disparities in student loan debt and the reproduction of the fragile black middle class. CDE Working Paper No. 2018-2. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin Madison. https://cde.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/839/2018/12/cde-working-paper-2018-02.pdf

[13] The Institute for College Access and Success. Student debt and the class of 2018. https://ticas.org/interactive-map/

[14] Barshay, J. (2017, Nov. 6). Federal data show 3.9 million students dropped out of college with debt in 2015 and 2016. Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/federal-data-shows-3-9-million-students-dropped-college-debt-2015-2016/

[15] Prosperity Now Scorecard. https://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by-location#state/ga

[16] University System of Georgia data.

[17] Scott-Clayton, J., & Li, J. (2016 Oct.). Black-white disparity in student loan debt more than triples after graduation. Economic Studies at Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/es_20161020_scott-clayton_evidence_speaks.pdf

[18] Georgia Student Finance Commission data.

[19] Federal Student Aid, U.S. Department of Education. FY 2016 official cohort default rates by state/territory. https://www2.ed.gov/offices/OSFAP/defaultmanagement/staterates.pdf

[20] Lee, J. (2020 Sep). Moving HOPE forward into the 21st century. https://gbpi.org/moving-hope-forward-into-the-21st-century/

[21] Carnevale, A., Jayasundra, T., & Gulish, A. (2016). America’s divided recovery: College haves and have nots. Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/americas-divided-recovery/

[22] Mezza, A., Ringo, D., & Sommer, K. (2019 Feb). Can student loan debt explain low homeownership rates for young adults? Consumer & Community Context. Federal Reserve Board Division of Research and Statistics. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-january-consumer-community-context.htm

[23] Ambrose, B. W., Cordell, L., & Ma, Shuwei. (2015 July). The impact of student loan debt on small business formation. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.