This blog was co-authored by Senior Policy Analyst Alex Camardelle and Research Associate Ray Khalfani

On March 13, 2020 the President of the United States declared a national emergency in response to the global coronavirus pandemic. To protect the public’s health, the Centers for Disease Control began recommending social distancing, with executive orders at the local, state and national level to follow. As the virus has reached thousands of Georgians now, it has spotlighted cracks in Georgia’s economy that are primed to worsen.

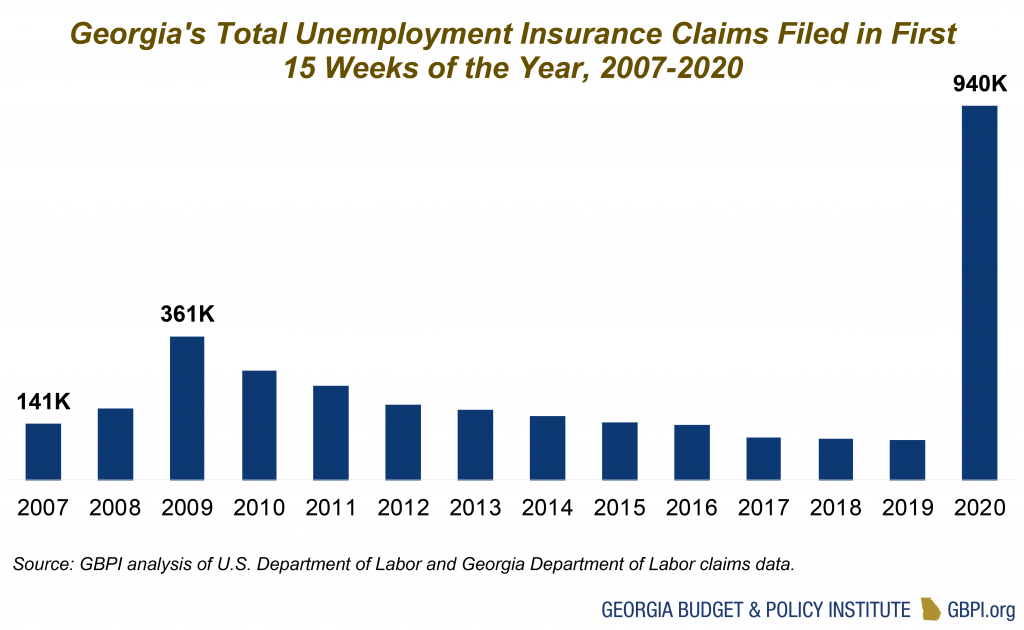

This is evident in the unprecedented numbers of workers turning to Georgia’s safety net right now. Laid off workers are rushing to the state’s unemployment insurance program at rates never seen before. We are just a little over a quarter into the year, and so far 940,000 Georgia workers have already filed for unemployment.

The state’s Labor Commissioner remarked that the majority of claims being filed come from workers in food services and accommodation jobs, where workers of color and women are overrepresented. These workers are also least likely to have the privilege of working from home and continuing to receive income from the job. We are already seeing disproportionate rates of joblessness among some workers. For example, despite making up 30 percent of Georgia’s labor force, Black workers account for more than half of recent unemployment insurance claims. It is important for us to take stock of where we were before this pandemic began to address these racial and gender disparities.

The state’s Labor Commissioner remarked that the majority of claims being filed come from workers in food services and accommodation jobs, where workers of color and women are overrepresented. These workers are also least likely to have the privilege of working from home and continuing to receive income from the job. We are already seeing disproportionate rates of joblessness among some workers. For example, despite making up 30 percent of Georgia’s labor force, Black workers account for more than half of recent unemployment insurance claims. It is important for us to take stock of where we were before this pandemic began to address these racial and gender disparities.

Demographics of Georgia’s UI claimers in March 2020 |

||

| Share of UI claimers | Share of Labor Force | |

Race/ethnicity |

||

| Black | 55% | 31% |

| White | 42% | 52% |

| Asian | 2% | 6% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1% | 11% |

Gender |

||

| Women | 46% | 48% |

| Men | 55% | 52% |

After the Great Recession, Georgia’s recovery strategy failed to prioritize job quality and on-ramps to meaningful employment. A tradition of disinvestment in the safety net and workforce development opportunities have disproportionately impacted workers of color and women, who, because of largely unaddressed sexism and racism baked into policy, were left furthest behind in the recovery years. Gender and racial inequities have always been a key feature of Georgia’s economy.

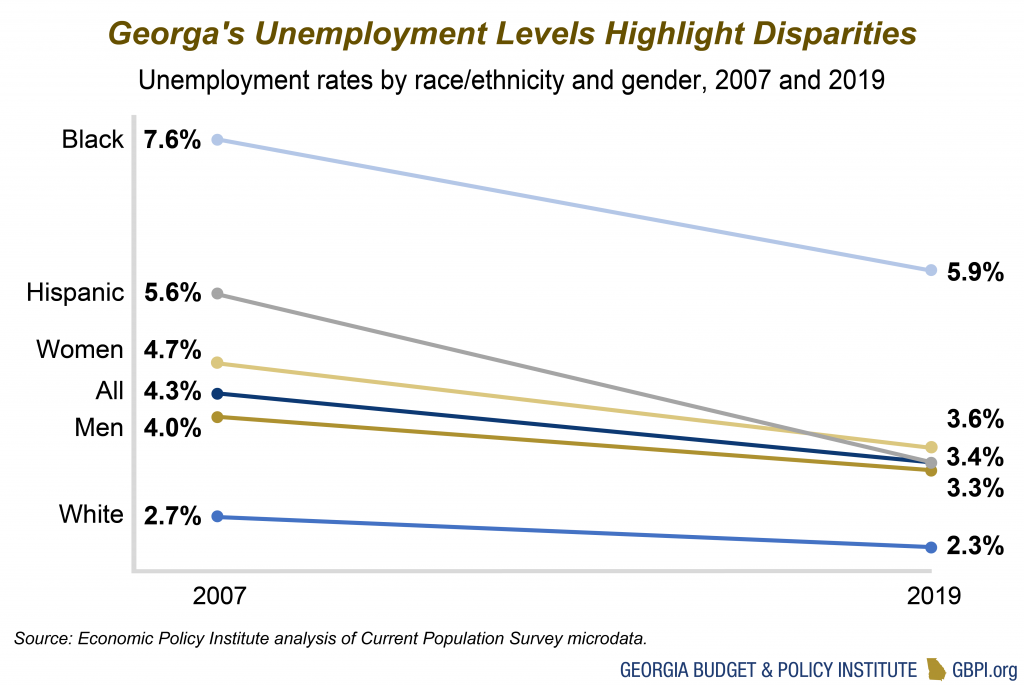

Today, Georgia’s unemployment rate has climbed to 4.2 percent for the first time since early 2018, reflecting what we feared about the impact of the coronavirus on the labor market. Prior to the pandemic, Georgia and the nation were experiencing historically low levels of overall unemployment. However, recovery from the Great Recession fortified inequities among women and people of color. For example, although unemployment rates have improved generally, the disparities among these groups remain pervasive.

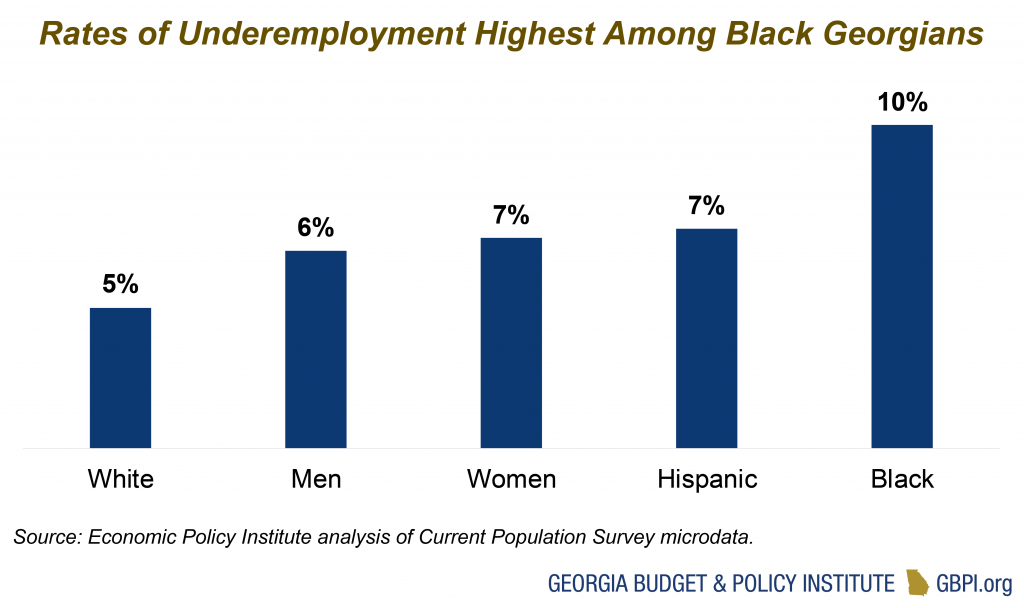

Although celebrated, the low unemployment levels are loaded with disparities, and thus are not indicative of the strength and prosperity of Georgia’s individuals and families. Additional measures are necessary. For example, despite historically low unemployment rates, cases of underemployment remain high as well. Underemployment refers to people who would rather work full-time but instead work part-time for economic reasons, as well as those who want a job but have not looked for work recently. This is also felt more sharply by Black Georgians. Ten percent of Black Georgians are underemployed, compared to just 5 percent of white Georgians.

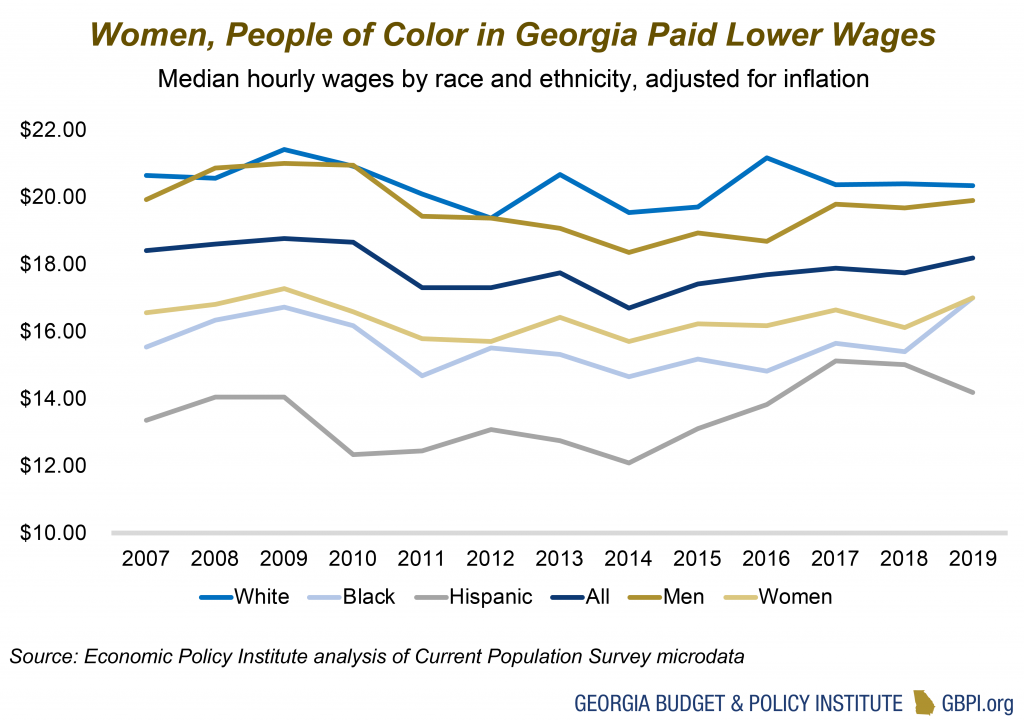

The median hourly wages for workers remained stagnant throughout the recovery period as well. For some, they may have never returned to pre-recession levels. This pandemic downturn has exposed a reality that was ignored for too long: too many people are only surviving, not thriving. Stubbornly low wages have stripped away the ability of women and people of color to establish enough savings and wealth to protect them from moments like this.

After the Great Recession began, it took 76 months for overall employment levels to return to pre-recession status but the pace of that recovery varied widely by race, ethnicity and gender. Meanwhile, experts are already estimating that the current pandemic downturn will extend well into 2021. To prevent worsening these inequities over the short and long-term, Georgia will need a robust and targeted strategy to support women and people of color throughout the economic downturn. But first, acknowledgement that the path to prosperity for all has not been prioritized in public policy and state fiscal decisions must be made clear. The post-coronavirus Georgia must resist reverting back to the status quo, where only a few consistently benefit from the recovery.