Key Takeaways:

- Nearly 60 percent of Georgia’s pre-pandemic labor force have turned to the unemployment safety net at some point during the last year.

- In February 2021, unemployment claims for Black Georgians were 52 percent higher than those of all other filers, and 71 percent higher than those of white Georgians alone.

- Hispanic and Black women have experienced at least 15 percent underemployment since the pandemic, while underemployment for Black men was 18 percent in the first quarter of 2021, more than any other group in Georgia’s workforce.

Recent historic federal stimulus packages have extended critical unemployment safety net programs, provided immediate cash aid to millions of employed and unemployed Georgians and provided state and local funding to jumpstart Georgia’s recovery. As a result, state lawmakers have an opportunity to target federal and state funding to rebuild Georgia’s economy through racial and gender equity-centered solutions that can support economic mobility for all Georgians. However, more than a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, data shows how some Georgians are beginning to recover, while others have experienced little to no recovery at all.

Accessing Georgia’s Unemployment System

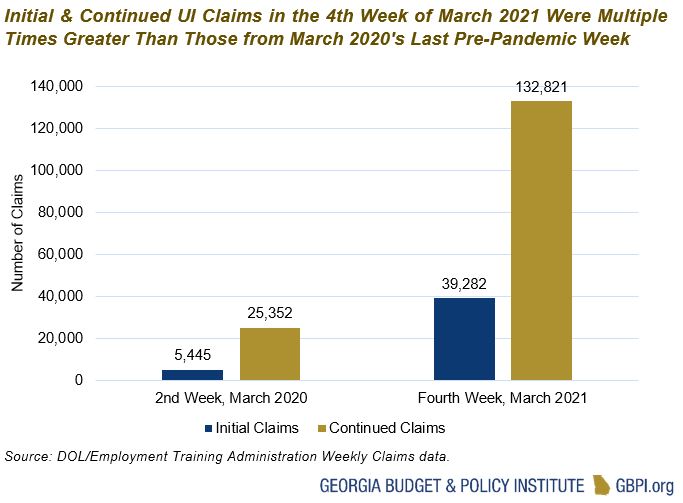

From mid-March 2020 to now, 4.6 million Georgians have turned to unemployment insurance. Excluding those with multiple episodes of job loss who therefore filed more than once as well as those who filed multiple claims for the same lost job, nearly 60 percent of Georgia’s pre-pandemic labor force have turned to the unemployment safety net at some point during the last year. New weekly claims continue to reflect high levels of joblessness, with over 39,000 Georgians filing for regular unemployment benefits during the week ending March 27, 2021. This is more than seven times the amount of new jobless claims that were filed during the last pre-pandemic week of March 2020. Continued claims—which signify people who continue to certify for pending payments after their initial claim, as well as those who certify to continue receiving payments – provide even greater context into persistent unemployment trends in Georgia. Continued claims at the end of March 2021 were more than five times greater than continued claims in the last pre-pandemic week of March 2020.

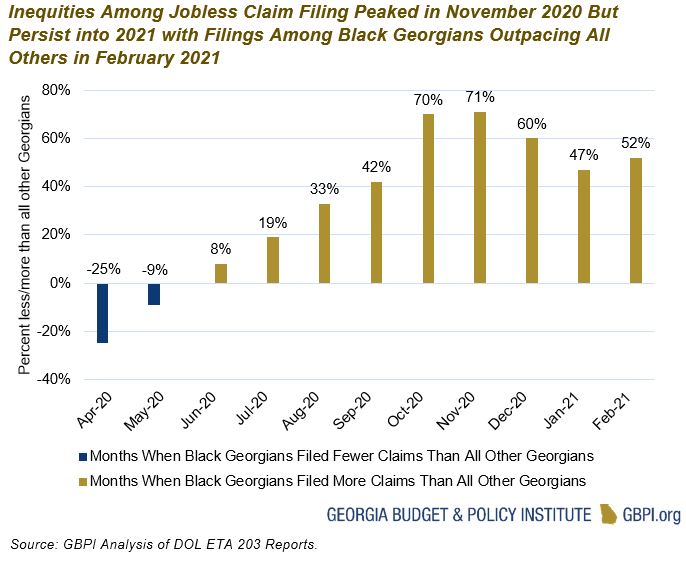

When disaggregating continued claims data, we see persistent unemployment disparities. Across race and ethnicity, Black Georgians remain overrepresented in the number of claims filed for jobless benefits. Across gender, women remain overrepresented in unemployment claims despite making up a much smaller portion of the labor force than men. While structural racism – a collection of discriminatory practices and racial biases across several facets of life, which include but are not limited to health care access, job access and retention, income, housing and education – has allowed these inequities to persist for decades, they reached their COVID pandemic peaks in the spring and summer of 2020 and have remained strikingly high well into 2021.

In February 2021, unemployment claims for Black Georgians were 52 percent higher than those of all other filers, and 71 percent higher than those of white Georgians alone. February unemployment claims for Georgia women remained higher than Georgia men, even though there are nearly 100,000 fewer women in the workforce than men, and they filed 32 percent fewer unemployment claims than men before the pandemic began.

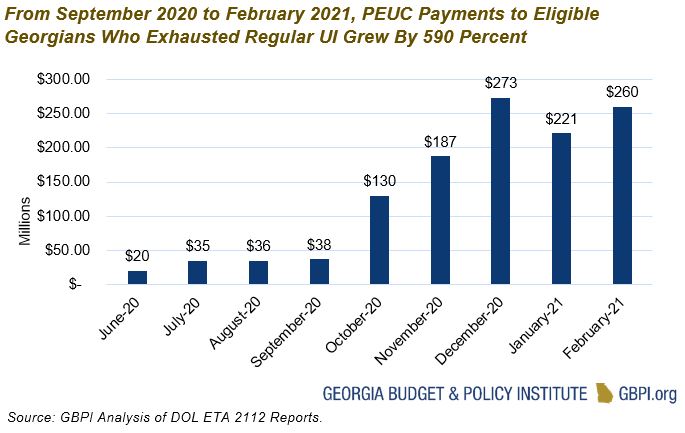

Over the past year, claims numbers have also shown continued need for federal unemployment safety net programs offering a floor for unemployed non-traditional workers and the long-term unemployed: the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program (PUA) and the Pandemic Extended Unemployment Compensation program (PEUC). Gig-workers, part-time workers and independent contractors suffering continued pandemic job loss have filed over 2,000 new PUA claims per week throughout March 2021. And the number of long-term unemployed Georgians who exhausted their regular state benefits and qualify for extended benefits through the PEUC program has continued to grow, as evidenced by PEUC program spending growth of 590 percent from September 2020 to February 2021.

The state’s unemployment system has service capacity challenges that have kept it from adequately serving the needs of recently and long-term unemployed Georgians. As a result, there is an urgent need for reform and modernization.

Georgia Job Trends: One Year Into The COVID Pandemic

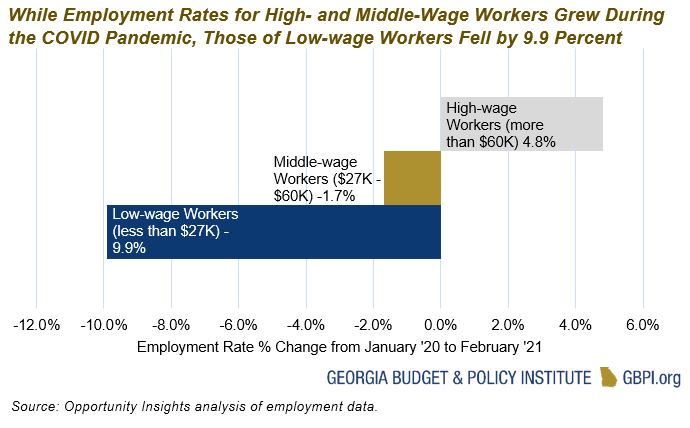

During COVID-19, there have been significant differences in employment outcomes among high-, middle- and low-wage workers in Georgia. From January 2020 to February 2021, employment rates among high-wage workers (those with incomes of $60,000 per year or more) grew by 4.8 percent. Employment among middle-wage workers ($27,000 to $60,000) declined by 1.7 percent. And employment among low-wage workers (below $27,000) declined by 9.9 percent.[1]

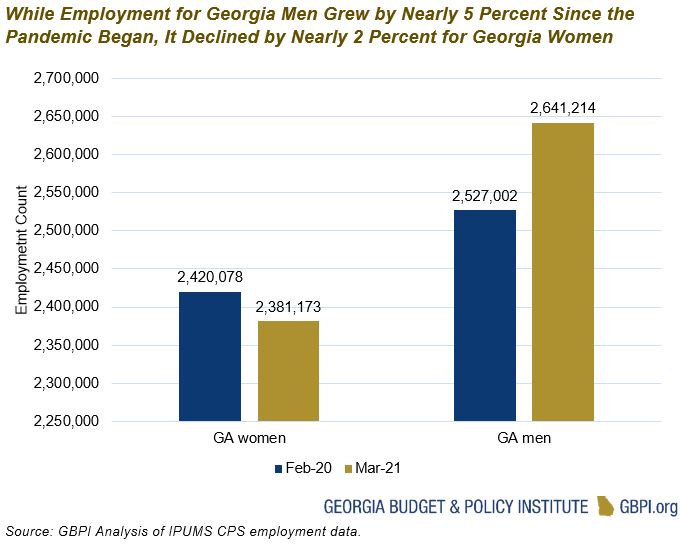

There have also been striking differences in employment outcomes across gender. From February 2020 to March 2021, employment for Georgia men has had a net growth of 5 percent, while having a net decline of 2 percent for Georgia women. These gaps between Georgia women and men in employment data speak to the trend of large exits of women from the workforce during this pandemic.

Georgia bled more than 609,000 non-agriculture jobs from February 2020 to April 2020. As of February 2021, nearly 396,000 of those jobs have returned. The hospitality industry has experienced the greatest impact, initially losing over 223,000 jobs from February 2020 to April 2020. Following job growth during late spring and summer of 2020, resurging pandemic outbreaks in the fall and winter months reversed those industry trends into another period of job losses. Overall, as of February 2021, 61 percent of hospitality industry jobs have returned since initial losses in April 2020.

People of color are disproportionately represented as hospitality workers and have typically performed “essential jobs” during the pandemic without hazard pay or benefits to compensate them for daily COVID risks taken while performing frontline, close-contact job tasks to earn paychecks to support their families. Today’s demographic distributions across Georgia’s hospitality industry, and others, have not been of random occurrence; rather, they are the results of intentional policies that have led to historical workforce segregation.

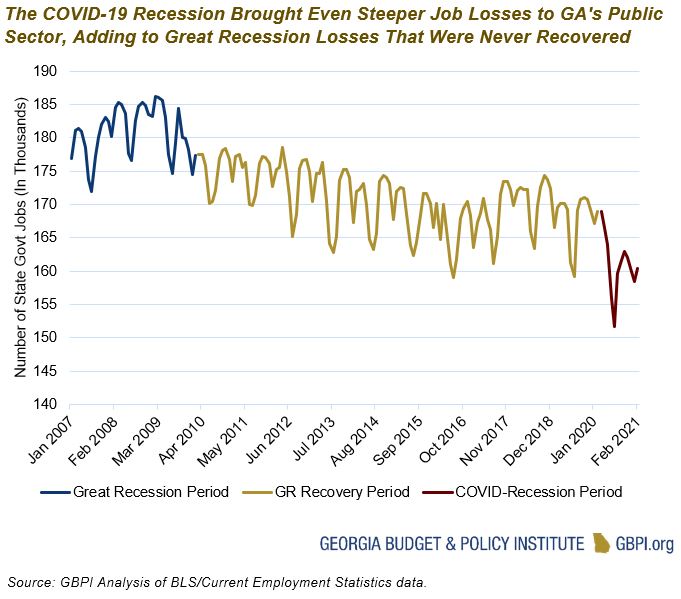

The pandemic also worsened public sector job losses that never recovered from the Great Recession and subsequent public sector workforce disinvestment. Just months into the COVID-19 crisis, the state and local public sector lost over 41,000 jobs. As of February 2021, 8,300 state government jobs have been regained, while 5,200 local government jobs have returned. This has resulted in a net job loss of 4.8 percent.

State government job losses during the COVID-19 recession period have been nearly 34 percent higher than during the Great Recession’s worst period of job loss. Furthermore, the trend of continuous disinvestment in public services that anchor thriving communities and subsequent employment loss in the public sector threatens to further erode the state’s public education system, public health services and the family economic mobility that it bolsters, which are vital to an equitable recovery. They also threaten more long-term damage to a sector of the labor market that has been a key employer of women and the Black workforce for several decades.

Unemployment in Georgia

Georgia’s March 2021 overall unemployment rate sits at 4.5 percent and has steadily decreased after its 12.6 percent peak in April 2020. Disaggregating this measure by race, ethnicity and gender, however, reveals that the COVID pandemic has compounded long-present disparities across Georgia’s workforce. Joblessness among Hispanic women shot up to over 19 percent during the second quarter of 2020,[2] while returning to low single-digit unemployment by the end of the year. Disproportionately high levels of joblessness among Black women, however, have remained persistent throughout the pandemic. At 7.5 percent in the first quarter of 2021, unemployment for Black women doubled all other groups during that period except for Black men and Hispanic women. Disproportionately high unemployment levels among Black and Hispanic women in Georgia reflect unique challenges for women workers of color, including racial and gender bias in the workforce, and how more women than men have been forced to choose between their professions and unpaid caregiving for their young children or elderly family members.

Underemployment in Georgia

While more attention is given to unemployment as a measure of labor market health, underemployment – particularly the segments of underemployed who can only find part-time work or job seekers in a discouraging job market who recently stopped looking – has become more widespread across each successive recession period, and therefore increasingly harmful to the recovery and economic mobility of Georgia’s labor force. Underemployment is measured as the share of the labor force that is either 1) unemployed, 2) working part-time but wants and is available to work full-time (“involuntary part-timer”), or 3) wants and is available to work and has looked for work in the last 12 months but has given up actively seeking work in the last four weeks (“marginally attached”).[3]

Hispanic and Black women have also suffered the highest and most persistent levels of underemployment throughout the pandemic. During the second quarter of 2020, 38 percent[4] of Hispanic women in Georgia’s workforce were underemployed, more than all other groups in that period and nearly double that of underemployed white women. Furthermore, Hispanic and Black women have experienced at least 15 percent underemployment since the pandemic, while underemployment for Black men was 18 percent in the first quarter of 2021, more than any other group in Georgia’s workforce.

Conclusion

Georgia’s overall 4.8 percent unemployment rate has reached its lowest point since the COVID-19 pandemic began. But when we look further into the numbers, we find disparities that have widened since the pre-pandemic period, and an economic crisis that has been persistent, particularly for women and those of color in Georgia’s workforce. This is evidenced by continued high unemployment insurance enrollment numbers among the long-term unemployed and recently unemployed, and significant gender, racial and ethnic disparities in unemployment and underemployment rates. Federal fiscal relief policies have provided a framework for recovery. State lawmakers however must decide how we target those federal investments, and how we can more effectively utilize state funding and revenue sources for lasting solutions that can foster greater equity across Georgia’s workforce.

End Notes

[1] Per data analysis from Opportunity Insights who gathered employment data from Earnin, Intuit, Kronos, and Paychex

[2] The unemployment rate analysis is based on IPUMS Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata, which produces slightly different numbers for some months than state employment statistics published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) that also incorporate other sources; however, the CPS microdata are the only timely and publicly-available source for disaggregated state-level employment data.

[3] Underemployment is measured and expressed in alignment with previous research and publications from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI)

[4] The underemployment rate analysis is based on IPUMS Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata, which produces slightly different numbers for some months than state employment statistics published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) that also incorporate other sources; however, the CPS microdata are the only timely and publicly-available source for disaggregated state-level employment data.