A set of sales tax breaks passed by Georgia lawmakers in 2012 is a growing hardship for city and county governments struggling to fund schools, parks, libraries and other essential services. The problem is felt most outside of metro Atlanta, due to the larger than expected local revenue loss from a generous new tax break for agricultural supplies, known as GATE (Georgia Agriculture Tax Exemption). The GATE exemption is whittling away a primary source of revenue for Georgia’s rural counties and small towns, leading some to raise property taxes for the first time in years. To make matters worse, the new tax break lacks oversight and is ripe for abuse.

A set of sales tax breaks passed by Georgia lawmakers in 2012 is a growing hardship for city and county governments struggling to fund schools, parks, libraries and other essential services. The problem is felt most outside of metro Atlanta, due to the larger than expected local revenue loss from a generous new tax break for agricultural supplies, known as GATE (Georgia Agriculture Tax Exemption). The GATE exemption is whittling away a primary source of revenue for Georgia’s rural counties and small towns, leading some to raise property taxes for the first time in years. To make matters worse, the new tax break lacks oversight and is ripe for abuse.

Georgia lawmakers passed a comprehensive package of tax changes in 2012 to remove state and local sales taxes from a range of goods and services, including electricity used in manufacturing and construction materials for some large developments. The package also expanded Georgia’s sales tax break for agriculture, which now allows farmers to buy most of their supplies tax-free. Farmers are exempt from both the 4 percent state sales tax and 3 percent local sales tax on feed, seed, tractors, plywood and dozens of other products ranging from chainsaws to pesticide.

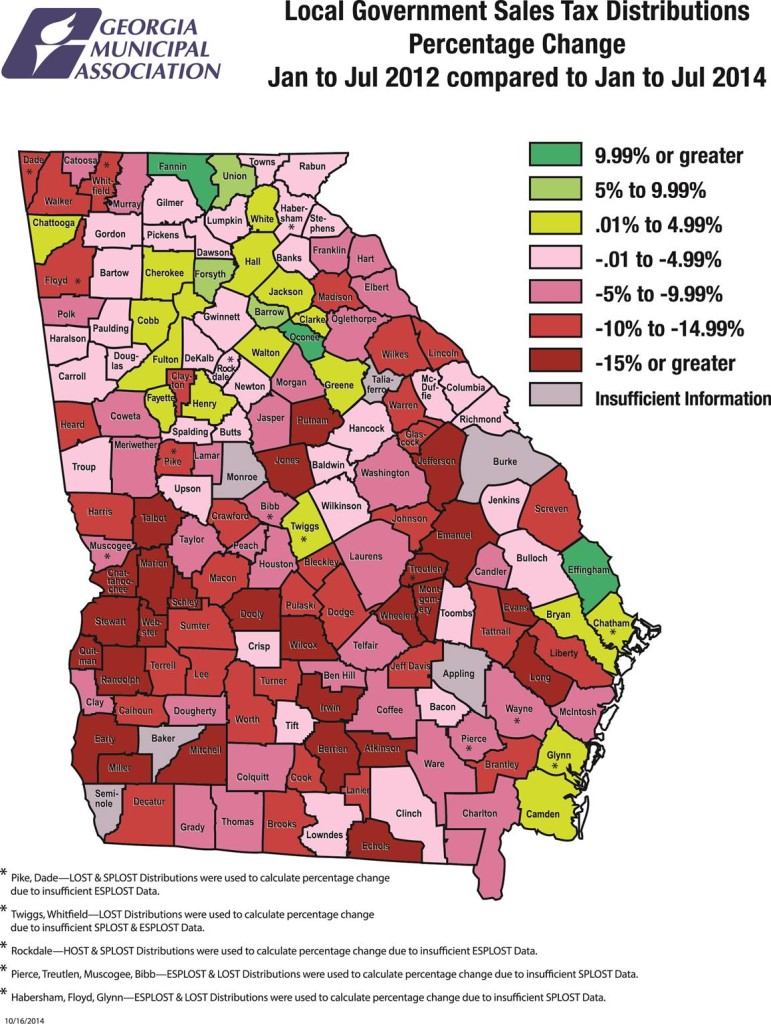

State experts originally estimated the cost of the farming tax break at only about $30 million a year to local governments statewide, but critics argue it’s likely far higher. And rural counties and small towns, in particular, are feeling the brunt of the losses. An in-depth review by the Georgia Municipal Association in October shows several counties in mid- and south-Georgia suffered sales tax drops of more than 15 percent from early 2012 to early 2014. Urban and suburban areas, meanwhile, saw smaller declines or even increases as illustrated in the map below.

This drop in local revenues makes it harder for rural communities to fund critical services taxpayers rely on, ranging from schools to fire protection and public safety. The city of Bainbridge, for example, laid off a quarter of its workforce since 2009 and halted construction of a downtown development project. Decatur County schools put off buying new computers and air-conditioned buses.

In response, some local governments are resorting to raising property taxes for the first time in years. In June, the city of Valdosta raised taxes on homeowners for the first time since 1992. Lowndes County, home to Valdosta, lost $2.3 million in sales tax revenue from 2012 to 2013 – a period when tax collections should have been rising alongside gradual economic growth.

GATE also lacks proper controls to make sure recipients don’t abuse the program, which could be costing local governments more money. Farmers who apply for the exemption get a wallet-sized card from the state that they later present to local retailers. But there’s no way to know if the cards are used as intended, as reported by the Atlanta-Journal Constitution. According to one anecdote, a man from Alabama bought $10,000 worth of tax-free lumber supposedly for a barn that he actually used to build a house.

Rampant reports of fraud followed GATE’s 2013 rollout. The state has yet to conduct an audit of the program, although one is planned for next year. Georgia issued more than 32,000 GATE cards as of November 2014, including about 1,200 to applicants from other states.

Georgia’s farmers are entitled to make a living and to be taxed fairly, but evidence is mounting the generous GATE exemption needs a second look. Lawmakers could improve it by limiting the tax benefit to fewer farmers, investing in stronger oversight or applying the exemption only to the 4 percent state sales tax – giving local governments the option to levy the 3 percent local tax or not. State lawmakers should closely consider these and other reforms when they return to work in January.