Introduction

Eliminating Georgia’s income tax would represent the largest transfer of wealth from working and middle-class families to high income individuals and corporations in state history. Doing so would dramatically push Georgia’s budget out of balance, given that the income tax has been the state’s single largest source of revenue since 1982. With Georgia already maintaining the nation’s seventh lowest level of overall state taxes per person, lawmakers seeking to emulate the handful of states without income taxes could also end up delivering the largest tax increase in modern state history to most households.[1] Furthermore, about three-quarters of Georgia’s state budget funds health care and public education (Fiscal Year (FY) 2026). If the state abandons its primary source of revenue, these vital services would be first in line for budget cuts that could threaten Georgia’s economy, children and families.

In FY 2025, Georgia raised more than half (56%) of its $34.8 billion in general fund revenues from income taxes, which amounted to $19.5 billion.[2] That revenue is split between $16.2 billion in personal income taxes (47% of general funds) and $3.3 billion in corporate income tax collections (9% of general funds). Although few details are usually offered in response to questions over how to replace the state’s largest source of revenue, the likeliest option is the sales tax.

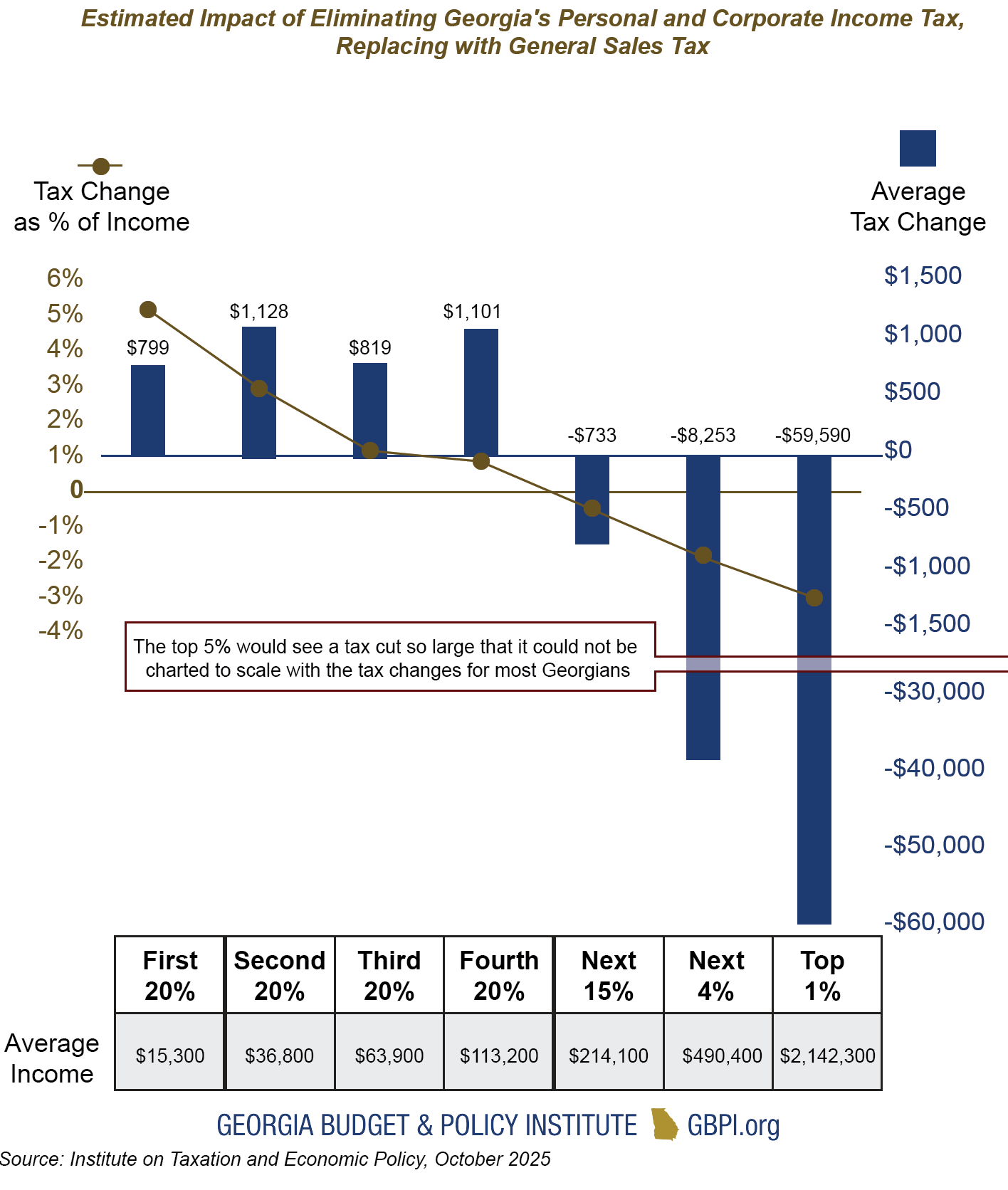

Georgia’s second largest revenue source is the sales tax, representing about 27% of general fund revenues or $9.3 billion raised in FY 2025. Replacing Georgia’s income tax with an enhanced sales tax would, on average, result in a net tax increase of about $1,000 annually for the first 80% of households.[3] Most savings from eliminating the personal income tax would go to relatively few beneficiaries at the very top of the economic ladder, while almost all savings from eliminating the corporate income tax would go out-of-state to large corporations.[4] For the first 80% of Georgians, the average tax increase under this proposed shift from income taxes to sales taxes is roughly equivalent to the cost of purchasing nearly a month of groceries.[5] Rather than seeing a tax cut, most Georgia families would feel the effects of higher prices on a day-to-day basis as a higher cost of living substantially outruns any potential savings from eliminating the income tax.

Georgia’s second largest revenue source is the sales tax, representing about 27% of general fund revenues or $9.3 billion raised in FY 2025. Replacing Georgia’s income tax with an enhanced sales tax would, on average, result in a net tax increase of about $1,000 annually for the first 80% of households.[3] Most savings from eliminating the personal income tax would go to relatively few beneficiaries at the very top of the economic ladder, while almost all savings from eliminating the corporate income tax would go out-of-state to large corporations.[4] For the first 80% of Georgians, the average tax increase under this proposed shift from income taxes to sales taxes is roughly equivalent to the cost of purchasing nearly a month of groceries.[5] Rather than seeing a tax cut, most Georgia families would feel the effects of higher prices on a day-to-day basis as a higher cost of living substantially outruns any potential savings from eliminating the income tax.

Overview of Georgia’s Income Tax System

Regressive taxes push lower and middle-income residents to pay a greater share of their earnings in taxes compared to higher income individuals and corporations who pay proportionately less. For example, when families shop for school supplies and daily necessities, those with lower incomes end up paying a higher share of their wages in sales taxes for these products than higher income families. Income taxes help to even this out by ensuring that those at the higher end of the economic ladder are assessed at least some state taxes on income that is otherwise likely to go untaxed in Georgia. A balanced system, which taxes both consumption through sales taxes and earnings through income taxes, helps to create a fairer playing field where those at different income levels pay a comparable share of their earnings in state taxes. This ensures that low- and middle-income households are not held back economically by shouldering an outsized share of the costs required to fund state government.

In other words, swapping income taxes for sales taxes means that those earning hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars would see a greater portion of their financial resources go untaxed, as the cost-of-living skyrockets for most Georgians because of higher sales taxes. While top earners see a windfall, middle-class and working families would face higher taxes on everything from diapers to clothing to eating at restaurants. These sales taxes add up to a big overall tax increase that is likely to far exceed any savings from the elimination of the income tax for all but the highest income households.

For much of modern state history, between 1937 and 2018, Georgia maintained a graduated income tax structure, in which the income tax rate increased with earnings before reaching the top rate of 6%, which was constitutionally capped at this level in 2014. Then, in 2018, Georgia’s top income tax rate was reduced to 5.75%. This initial rate cut was followed by the implementation of a multi-year flat tax plan that took effect in January 2024. Since then, state leaders have acted twice to reduce Georgia’s now-flat income tax rate to 5.19%, while also aligning its corporate income tax rate to the same level as its personal income tax.

Cumulatively, these reductions to Georgia’s income tax lowered baseline state revenues by about $1.6 billion per year.[6] Rather than replace these revenues with other taxes, policymakers opted to use a portion of the state’s recent surplus to cover the cost. However, with FY 2025 marking the first year since 2020 that Georgia has spent down part of its surplus reserves, the runway for further surplus-financed tax cuts appears to be reaching an end as revenue collections have fallen closely in line with state spending.

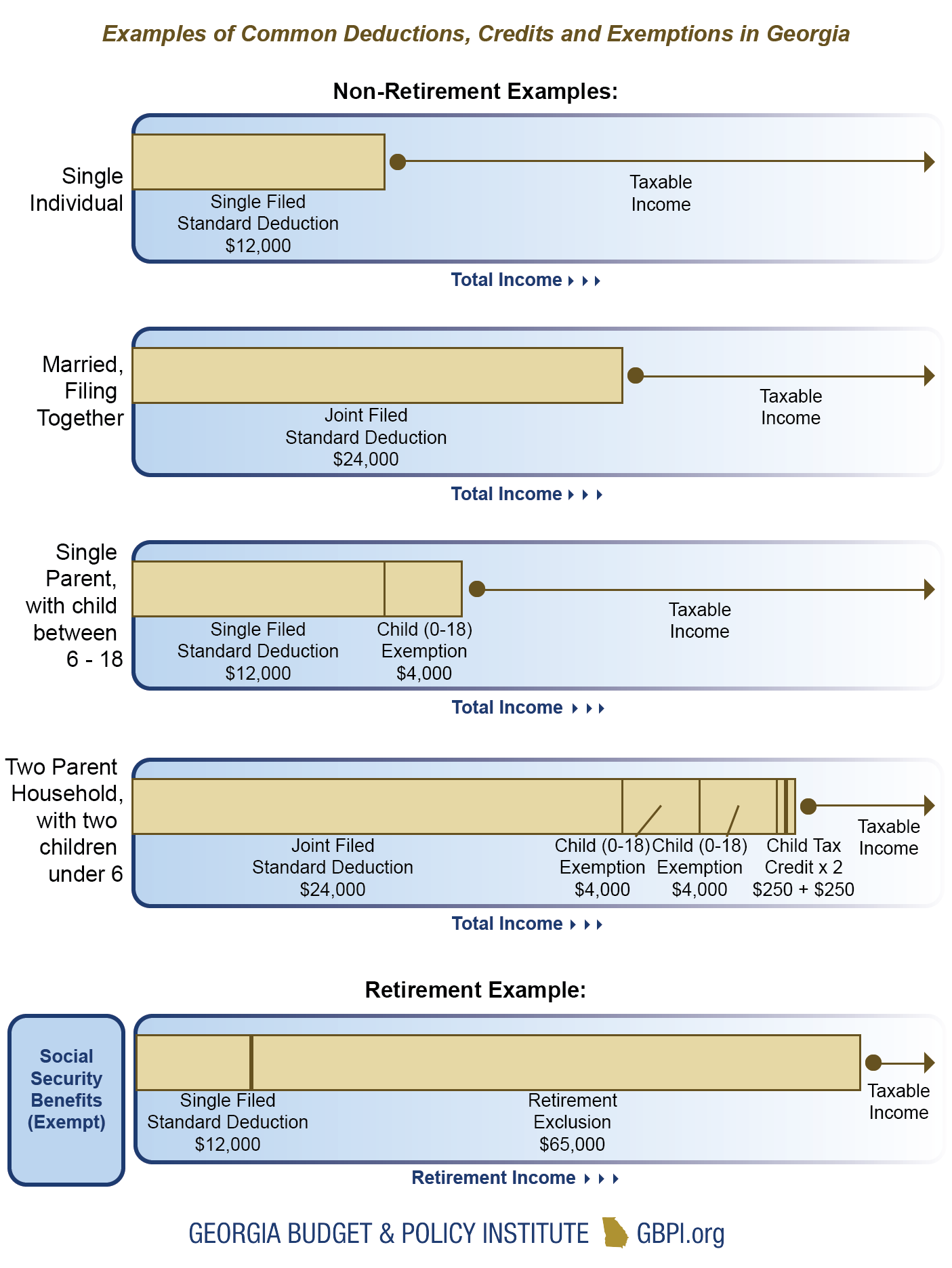

On average, most Georgians pay an effective state income tax rate of less than 3% of their total earnings.[7] This is far below the statutory tax rate of 5.19% and is the result of tax code provisions that exempt income from taxation or offer credits to filers, effectively reducing or eliminating income taxes, depending on each household’s circumstances. A variety of these state tax expenditures were created to incentivize or reward certain behavior, such as having children, serving in the military, owning a home or starting a business.

Beyond the statutory tax rate of 5.19%, filers arrive at their taxable income by applying these exemptions, exclusions, adjustments, deductions and credits, and are then assessed any applicable taxes. For example, Social Security benefits are exempt from Georgia income taxes, as is up to $65,000 of retirement income per person.[8] All taxpayers are also eligible for the state’s full standard deduction, which is valued at $12,000 for individuals or $24,000 for those who are married and file taxes together. Taxpayers can choose between taking the standard deduction or itemizing, usually selecting whichever option offers greater savings. About 88% of Georgians now use the standard deduction.[9] Those who itemize can select from a range of deductions, which include mortgage interest, medical expenses, student loan interest payments, charitable contributions and a wide range of other possible tax breaks.

Parents of children under 19 (under 24 if they are full-time students) or those with other dependents are also granted an exemption of $4,000 for each qualifying dependent. This year, lawmakers also created a nonrefundable Child Tax Credit of $250 per child under the age of six, which taxpayers are eligible for regardless of whether they itemize or take the standard deduction. This means that a Georgia family of four (with two children under six) is not assessed any state income taxes on at least the first $32,500 of their earnings. Taken together, these provisions demonstrate the benefits of maintaining the state income tax code, allowing Georgia’s leaders to craft tax policy that directly influences the economic landscape and reflects state priorities.

How Do “No Income Tax States” Balance Budgets?

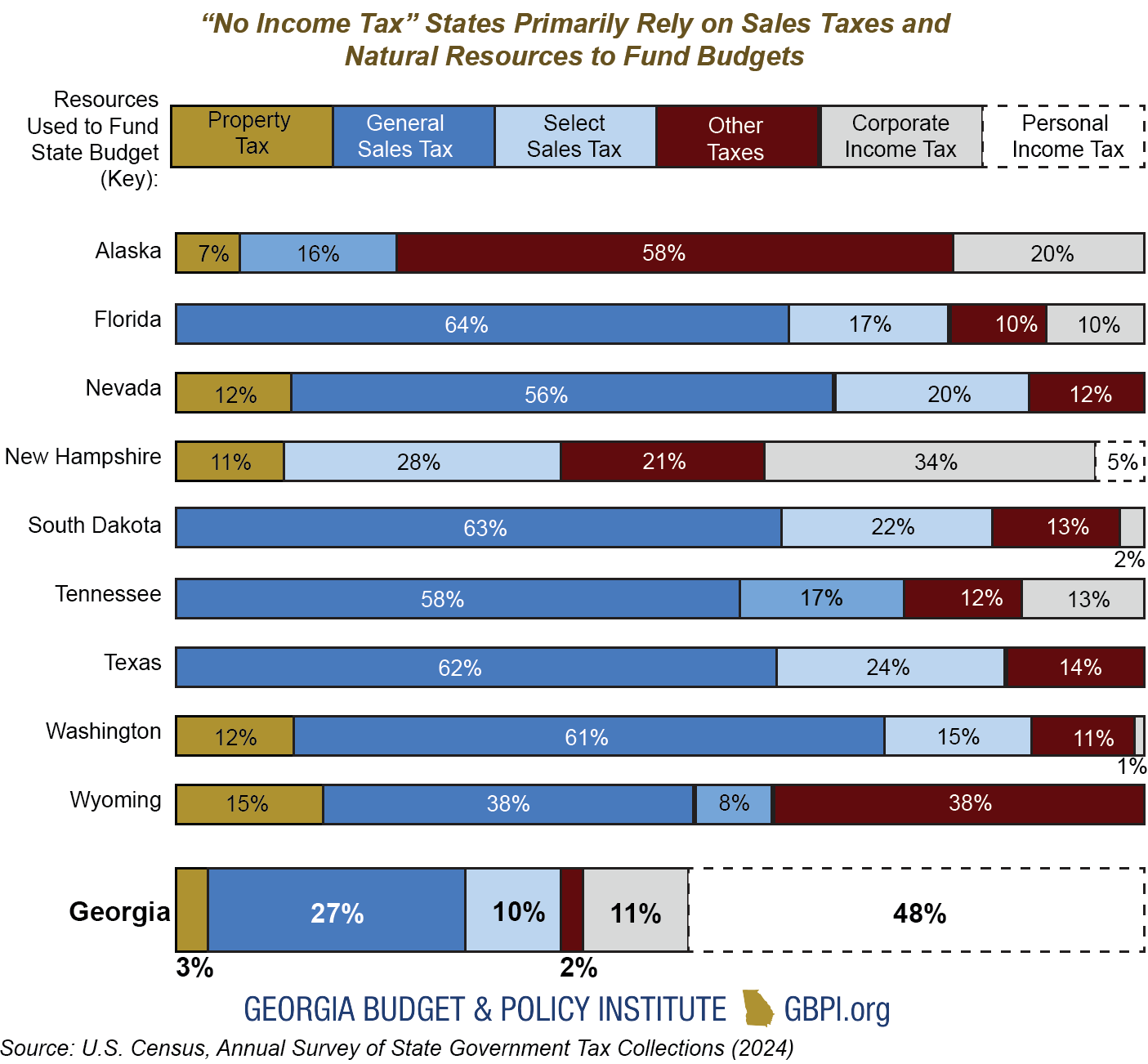

Nine states are commonly understood to fall into the category of states without an income tax: Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington and Wyoming. Still, among these states, only three maintain revenue systems that do not raise income taxes of any kind (Nevada, Texas, and Wyoming), while four others generate less than 13% of overall state revenues from limited taxes on some types of income (Florida, South Dakota, Tennessee and Washington).[10] The remaining two, Alaska and New Hampshire, do not have a personal income tax, but do maintain substantial corporate income taxes, which raise 20% and 34% of overall state revenue, respectively.[11] Florida, South Dakota and Tennessee also assess corporate income taxes, which range from 2% to 13% of overall tax collections. Five of these states levy state property taxes, which raise between 7% to 15% of total revenue.

Most “no income tax” states are heavily reliant on sales and excise taxes, which comprise at least 75% of overall revenue in Florida (80%), Nevada (76%), South Dakota (84%), Tennessee (75%), Texas (86%) and Washington (76%). Alaska raises most of its revenue from the economically dominant oil and gas industry, while Wyoming levies a major severance tax on mineral extraction. New Hampshire, on the other hand, assesses substantial taxes on businesses, along with a statewide property tax rate. Georgia does not collect state property taxes (aside from on vehicles), and the extraction of oil and natural minerals are not a large part of its state economy, limiting the possibility of replicating these sources of revenue.

Among these nine states, Alaska is the only one that has repealed a previously enacted broad-based income tax that resembled Georgia’s. This was only possible because Alaska tapped its abundant oil reserves, and, in recent years, Alaska’s legislature has backtracked by approving new taxes on corporate income. While numerous other states have attempted to eliminate existing income tax systems, none have been successful, in large part because of the painful tradeoffs that would worsen the economic position of most residents. Evaluating the landscape of revenue systems in these nine states demonstrates that the sales tax is likely the only viable substitute that could raise enough revenue to replace Georgia’s income tax.

Moreover, several states without income taxes assess higher levels of overall state taxes per resident, including Nevada, Tennessee, Washington and Wyoming.[12] Last year (2024), eight of 11 Southern states and almost all Georgia’s neighbors collected a higher overall amount of state taxes per person than Georgia. On average, residents of South Carolina paid $281 (9%) more than Georgians, while those in Tennessee paid $334 more (11%). In North Carolina, which is often compared to Georgia, residents paid $533 (18%) more in annual state taxes.[13]

Since 1997, Georgia has earned a AAA bond rating from the three major credit rating agencies, allowing the state to borrow money at the most favorable interest rates and to stretch taxpayer dollars as far as possible.[14] By abandoning its long-standing revenue system, the state would risk jeopardizing this economic advantage, which would make it more expensive to finance long-term infrastructure and capital projects. In fact, most states without broad-based income taxes have lower credit ratings than Georgia, including Alaska, Nevada, New Hampshire, Washington and Wyoming.

Importantly, Georgia’s economy continues to outperform most states without income taxes. In 2024, Georgians earned a higher median income than residents of Florida, Tennessee, Texas, South Dakota and Wyoming.[15] Looking at long-term economic trends, Georgia has also surpassed most states without income taxes in labor productivity, growing at a faster rate from 2007 to 2024 than Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota and Wyoming.[16] This trend continued into last year, as growth in labor productivity in Georgia far surpassed most “no income tax” states, including Tennessee and Florida, while tying Texas.[17] Rather than chasing after state economies that are performing worse than our own, policymakers could improve Georgia’s standing by focusing on pro-growth policies that address real gaps in areas like health care, child care and education.

The Costly Consequences of Eliminating Georgia’s Income Tax

Georgia maintains a relatively flat revenue system, in which most households pay a combined overall state and local tax rate that is equivalent to 9-10% of their annual income.[18] However, those who earn the least are likeliest to pay the greatest share of their earnings in total state and local taxes at 10.3%, while those in the top 1% currently pay the lowest effective rate of 6.9%. Sales and property taxes hit low- and middle-income families the hardest by consuming a larger share of their economic resources, while income taxes help to ensure higher income households and corporations pay their fair share. This adds balance to the revenue system so that low- and middle-income families are not overtaxed. Importantly, income taxes also generally keep pace with economic growth, helping to fund key public services like education and health care (73% of all state spending in FY 2026) and to avoid the sharp dips that could otherwise occur during an economic downturn. Without income tax revenue, Georgia’s healthy fiscal outlook could rapidly turn upside down.

Just 14% of all personal income tax revenues are collected from the first 60% of Georgia earners, making up to $85,000 annually.[19] Although working- and middle-class families pay less in income taxes, they more than make up for their fair share through existing sales taxes, property taxes, fines and fees. These figures demonstrate why revenue proposals centered on cutting the income tax offer relatively few potential benefits to most Georgians, while inevitably skewing the state’s revenue system toward the wealthiest.

Looking at the effects of eliminating Georgia’s personal income tax alone, without considering the tax increases that would replace it, demonstrates that 45% of all savings ($7.6 billion annually) would go to those among the top 5% of earners, who make more than $332,000 per year.[20] About 71% of all tax reductions from eliminating the personal income tax, or about $11.8 billion, would go to those earning more than $153,000 annually.

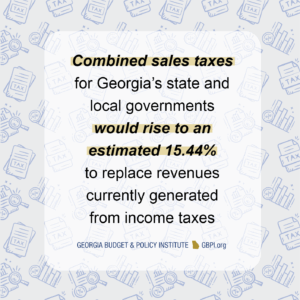

With the seventh lowest level of state taxes per person in the nation, Georgians paid an average of $3,009 in overall taxes in 2024.[21] This includes about $1,102 in sales taxes and $1,433 in personal income taxes.[22] To recoup the same amount of revenue raised through Georgia’s personal and corporate income tax, the state would need to levy a general sales tax of 12.02%, tripling the current 4% rate. Combined with local sales taxes, that would mean an average sales tax rate of 15.44% statewide, up from the current average of 7.42%. Alternatively, it is also possible that Georgia could begin assessing new sales taxes on things that are currently untaxed, such as health care, manufacturing or legal services. However, such changes would be complex and require adding sales taxes to a multitude of new areas that would drive up costs for various industries as well as the cost of living for households at-large.

With the seventh lowest level of state taxes per person in the nation, Georgians paid an average of $3,009 in overall taxes in 2024.[21] This includes about $1,102 in sales taxes and $1,433 in personal income taxes.[22] To recoup the same amount of revenue raised through Georgia’s personal and corporate income tax, the state would need to levy a general sales tax of 12.02%, tripling the current 4% rate. Combined with local sales taxes, that would mean an average sales tax rate of 15.44% statewide, up from the current average of 7.42%. Alternatively, it is also possible that Georgia could begin assessing new sales taxes on things that are currently untaxed, such as health care, manufacturing or legal services. However, such changes would be complex and require adding sales taxes to a multitude of new areas that would drive up costs for various industries as well as the cost of living for households at-large.

If Georgia replaced its existing income tax with a general sales tax, the first 20% of households, about 1 million filers who make up to $25,600 annually, would experience a massive tax increase, a net loss of 5.21% of their annual earnings or a tax increase of about $800 annually.[23] Similarly, the first 80% of households, about 3.9 million filers who make up to $153,000 annually, would experience comparably large tax increases, reducing their take-home earnings between 1% to 5%, with the average net tax increase estimated at $963 per year. To see a tax cut, households would generally need to earn more than $153,000 per year, with the largest share of savings directed to those earning over $836,000 per year. Those in the top 1%, with an average annual income of $2.1 million, would see a net benefit of nearly $60,000 per year, underscoring how skewed Georgia’s tax system would become if the state traded income taxes for higher sales taxes.

Worse yet, approximately 94% of tax savings from eliminating the state’s corporate income tax would flow out of state.[24] This reflects, in part, relatively recent structural tax changes that delivered large tax reductions to businesses of all types and sizes. Implemented first under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 and more recently made permanent by 2025’s H.R. 1, many businesses now receive a major tax break by paying taxes at the individual level rather than through the corporate income tax. In fact, Georgia’s Department of Revenue (DOR) reports that, last year, most of Georgia’s corporate taxable income was reported by corporations based out-of-state.[25]

Higher sales taxes would almost certainly widen existing racial disparities in wealth and income, making Georgia’s tax code less fair and more inequitable. Without sufficient revenue, Georgia would also struggle to make needed investments in addressing other gaps in health and educational outcomes for already under-resourced communities. Ultimately, shifting from income taxes to sales taxes would set back the state’s economy as a whole and make it more difficult for Georgians to climb up the economic ladder. Simply put, replacing Georgia’s income tax with sales taxes would initiate the largest transfer of wealth from working and middle-class families to high-income individuals and corporations in Georgia history.

Major Revenue Considerations on the Horizon

In July of this year, President Trump signed into law H.R. 1, formerly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. H.R. 1 has a similarly regressive distribution of tax cuts as the elimination of the state income tax. The legislative package offers over $15.2 billion in overall annual tax reductions statewide, with 73% of those benefits going to the top 20% of Georgia earners ($11.1 billion).[26] Beyond extending $10.9 billion in tax cuts already in effect that would have expired in December 2025 under the TCJA of 2017, the legislation authorizes an estimated $4.3 billion in new tax reductions for Georgians. Approximately 90% of these new tax cuts ($3.9 billion) will benefit those in the top 20% of households, while a majority, 52% ($2.2 billion), will go to those in the top 5%, earning more than $332,000 per year.[27] Because the legislation is partially financed through deep cuts to health care through Medicaid and food assistance through SNAP, the Congressional Budget Office projects that the first 20% of households, those earning the lowest incomes, will lose money and resources as a result of the legislation.[28] Those in the bottom 10% will bear the brunt of these cuts, experiencing a net loss equivalent to $1,200 annually (3.1% of income).

While the federal government is financing tax cuts largely through deficit spending, the state must balance its budget each year. This balanced-budget requirement limits the state’s options to spending cuts or revenue-neutral tax shifts, in contrast to the federal government’s ever-increasing deficits that ultimately add to the national debt and contribute to higher levels of inflation and interest rates.

During the 2026 legislative session, Georgia lawmakers will also face the decision of whether to conform the state tax code to match both existing (but recently renewed) federal tax measures and provisions created this year. New federal tax provisions include tax exemptions for businesses, an expansion of 529 accounts for private K-12 tuition and higher education expenses, “Trump Accounts” for newborns, an increase to the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit and a variety of other measures that could affect Georgia.[29] H.R. 1 also includes temporary exemptions on some income earned from tips and overtime from 2025 to 2028, which Georgia lawmakers could also include in the state tax code.[30] Accepting some or all of these changes would lead to revenue losses that further weaken the state’s fiscal position in advance of potential reductions to Georgia’s income tax rate.

While not always part of the legislative debate around conformity, lawmakers would be wise to consider lifting the state’s standard deduction to match its federal counterpart, from $12,000 for single filers and $24,000 for those who are married filing jointly to $15,750 and $31,500 respectively. Georgia’s leaders could also consider moving the state’s $250 Child Tax Credit further in line with the federal version, which was recently enhanced to $2,200 per child (up to age 18) under H.R. 1. Increases to the standard deduction would benefit most households by exempting a larger share of income from state taxes. At Georgia’s current 5.19% flat income tax rate, increasing the state standard deduction to match its federal counterpart would reduce taxes by up to $195 for individuals and up to $389 per year for married couples. Growing Georgia’s Child Tax Credit and making it refundable, so that families could claim its full value regardless of how much they earn, could lift take-home pay for working and middle-income families by even more.

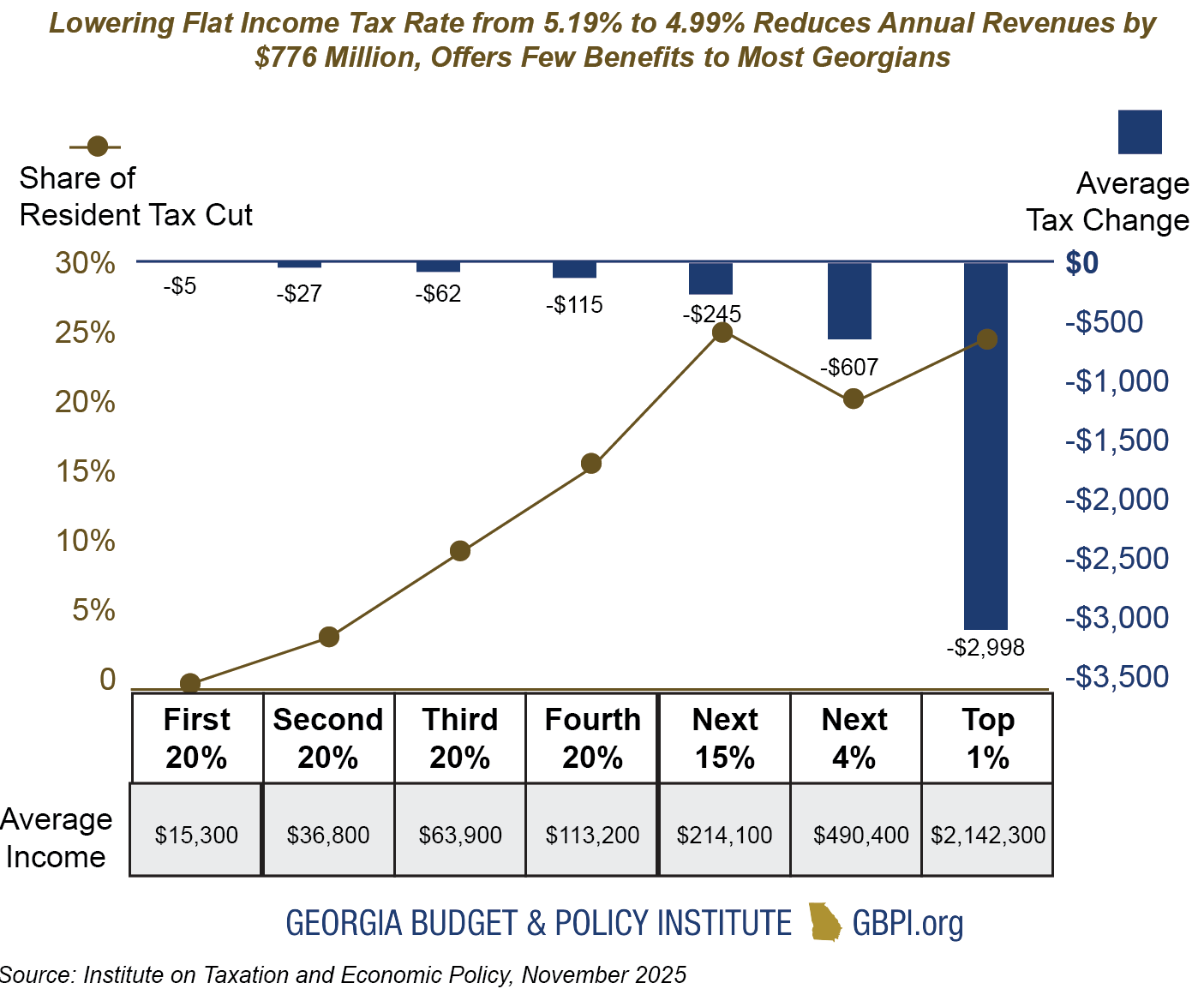

Aside from eliminating the income tax outright, some Georgia lawmakers have also advocated accelerating the flat tax plan that was initially approved in 2022 under House Bill 1437 by immediately reducing the state’s flat tax from 5.19% to 4.99% next year. Following similar actions in 2024 and 2025, most benefits would again go to those with the highest incomes and corporations. Under this $776 million proposal (FY 2027), approximately 70% of $684 million in annual personal income tax reductions would go to those with incomes in the top 20%, while about 94% of $92 million in corporate tax cuts would flow out of state.[31] Middle income households, earning an average of $64,000 annually, would see an average tax savings of less than $77 per year. These figures demonstrate that cutting the state’s flat income tax rate remains an extremely costly and highly inefficient way to deliver meaningful savings to most Georgians.

Some have suggested following Iowa’s plan for establishing a reserve account dedicated for tax reductions as a way to circumvent Georgia’s balanced budget requirement and allow for income tax cuts that the state could not otherwise afford.[32] Checking in on Iowa’s recent experience should caution policymakers to think twice about this fiscally irresponsible approach. Iowa recently reported an estimated $1.3 billion budget deficit (14%) for the current fiscal year, with revenues expected to fall far short of the state’s $9.4 billion budget.[33] Further, Iowa consistently ranks among the nation’s worst state economies, demonstrating that state income tax cuts are not a panacea for growth.[34] Assessments of Iowa’s failing economic position raise a glaring question: why would Georgia follow the lead of one of the nation’s worst economies and a state that is running a double-digit structural deficit? This example serves as a cautionary tale, where unfunded tax cuts and budget gimmicks can rapidly spiral into a fiscal crisis, even if lawmakers set aside funding to temporarily cover immediate deficits. Over the long term, this is a recipe for deep budget cuts, economic uncertainty and an ongoing fiscal crisis that could have been averted with a genuinely balanced budget.

Conclusion

For 12 years, Georgia’s leaders have touted the Peach State as the nation’s best for business, citing industry magazine rankings.[35] Now, state lawmakers, national lobbyists and interest groups are pushing for Georgia to upend its state budget and risk its prized AAA bond rating by eliminating the state’s income tax. Alternatively, Georgia could consider scaling back or eliminating corporate tax credits that send a large share of benefits out of state or to relatively few beneficiaries, such as the state’s $900 million film tax credit, and repurposing those funds to benefit working families.[36] However, if the state eliminates its personal or corporate income tax entirely, the bulk of these credits would cease to exist (with no income taxes to offset), and therefore, could not be used to finance the cost of tax reductions or investments.

Some elected officials have promised that eliminating the state income tax would lift incomes for Georgians by upwards of 5%. On the contrary, it would likely mean the opposite for the majority of Georgia families, amounting to the largest tax increase in modern state history for most. Rather than supercharging the state’s existing sales tax or levying new taxes across the economy, state leaders should pause to reevaluate their goals for Georgia’s revenue system and economy. Do we want to live in a state where families pay higher taxes to shield multinational corporations and the wealthiest from paying a comparable share of their income in state taxes? While eliminating the income tax may appear attractive as a political talking point, the reality is that it would make Georgia’s tax system less fair and harm the vast majority of families.

State leaders should reject regressive changes to the fiscal formula that has helped Georgia to surpass neighboring states in population and economic growth.[37] Instead, Georgia’s leaders can double down on proposals that have already demonstrated clear benefits statewide and across the nation: increasing the state’s standard deduction to match its newly enhanced federal counterpart, investing in growing the Child Tax Credit, enacting an Earned Income Tax Credit and addressing deep needs in health care and child care.[38] These proposals would expand the middle-class by prioritizing the well-being of Georgia’s children and families, rather than rewriting the tax code for the benefit of large corporations and those already earning the highest incomes.

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Census Bureau. (2025, April). 2024 annual survey of state government tax collections and state intercensal population estimates, estimates as calculated by author. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/stc/data/datasets.html “STC_Historical_DB (2024)”; https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html

[2] Georgia State Accounting Office. (2025, October 15). State of Georgia Revenue and reserves report, fiscal year ended June 30, 2025. https://sao.georgia.gov/swar/grr

[3] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, October). The first 80% of Georgia households would see an average tax increase of $963 per year under proposals to trade existing income taxes for a higher general sales tax.

[4] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, October). Approximately 71% of total tax reductions from eliminating the personal income tax would go to Georgians in the top 20%, earning over $153,000 per year. About 94% of total tax reductions from eliminating Georgia’s corporate income tax would go out-of-state.

[5] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. (2025, August). Official USDA Thrifty Food Plan: U.S. Average, August 2025. https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/cnpp-costfood-tfp-august2025.pdf; Boyce, H. (2025, February 19). Despite sharp grocery price hikes, Georgia remains one of the South’s most affordable. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/pulse/groceries-are-up-25-but-us-rankings-show-georgia-could-have-it-worse/JCRK4VNUPZBW3LS7624T6M3OFM/;

[6] Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2024, February 6). Fiscal note, House Bill 1015 (LC 50 0620EC); Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2024, February 21). Fiscal note, House Bill 1023 (LC 50 0662); Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2025, February 26). Fiscal note, House Bill 111 (LC 59 0028-EC); Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, November 5).

[7] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, October).

[8] Georgia Department of Revenue. (2025, November 1). Retirement income exclusion. https://dor.georgia.gov/retirement-income-exclusion

[9] IRS. (2025, January). Statistics of Income Division, Individual Master File System.

[10] U.S. Census Bureau. (2025, April). 2024 annual survey of state government tax collections. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/stc/data/datasets.html

[11] Ibid.

[12] U.S. Census Bureau. (2025, April). 2024 Annual survey of state government tax collections and 2024 state intercensal population estimate, as calculated by author. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/stc/data/datasets.html; https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html

[13] Ibid; In 2024, Georgia collected per capita total state taxes of $3,009.09. South Carolina collected per capita total state taxes of $3,290.21; Tennessee collected per capita total state taxes of $3,342.64; North Carolina collected per capita total state taxes of $3,541.98.

[14] Office of Governor Brian Kemp. (2025, July 15). Gov. Kemp: Georgia’s AAA bond rating reaffirmed by rating agencies. https://gov.georgia.gov/press-releases/2025-07-15/gov-kemp-georgias-aaa-bond-rating-reaffirmed-rating-agencies

[15] U.S. Census Bureau. (2025, September). Income in the United States: 2024. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2025/demo/p60-286.html

[16] Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, May 29). Productivity by state – 2024. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/prin4.pdf

[17] Ibid.

[18] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2024, January). Georgia: Who Pays? 7th Edition. https://itep.org/georgia-who-pays-7th-edition/

[19] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, October).

[20] Ibid.

[21] U.S. Census Bureau. (2025, April). 2024 Annual survey of state government tax collections and 2024 state intercensal population estimate, as calculated by author. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/stc/data/datasets.html; https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html

[22] Ibid.

[23] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, October); IRS. (2025, January). Statistics of Income Division, Individual Master File System.

[24] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, October).

[25] Georgia Department of Revenue. (2025, September 16). 2024 annual and statistical report. https://dor.georgia.gov/annual-and-statistical-report

[26] Wamhoff, S., Ettlinger, M., Davis, C., & Whiten, J. (2025, July 22). How will the Trump megabill change American Taxes in 2026? Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/how-will-trump-megabill-change-americans-taxes-in-2026/

[27] Ibid.

[28] Congressional Budget Office. (2025, August 11). Distributional effects of Public Law 119-21. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2025-08/61367-Distributional-Effects.pdf

[29] H.R. 1 (2025) makes a variety of changes to the federal tax code. Each legislative session, Georgia lawmakers traditionally consider whether to “conform” to adopt these changes as part of the state tax code. This process aligns federal and state tax policies but also has corresponding effects on revenue collections. These changes include an expansion of the tax exclusion for Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) gains, which allow companies with assets of up to $75 million to exclude certain capital gains from taxation. If Georgia adopts conformity with this change, it would reduce state revenues by an estimated $26.1 million in 2026. (See Austin, S., and N. Johnson. (2025, October). Quite Some BS: Expanded ‘QSBS’ giveaway in Trump tax law threatens state revenues and enriches the wealthy. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy). Other business tax changes include 100 percent “bonus depreciation” for machinery and equipment (Title VII, Section 70301), up from 40% in 2025; as well as a return to the pre-TCJA rules for deductions of domestic research and experimental expenditures (Title VII, Section 70302). This is a shift from the post-2022 tax rules, in which businesses could only deduct one-fifth of these expenditures in the year incurred and another one-fifth for the subsequent four years. H.R. 1 also allows businesses to deduct greater amounts of interest expenses (Title VII, Sections 70303 and 70342), along with reduced effective federal tax rates on “Foreign-Derived Intangible Income” and “Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income” (Title VII, Sections 70321-70323). The legislation also renews the Opportunity Zones Program (Title VII, Section 70421), which allows individuals and corporations to defer or exempt capital gains taxes on the sale of most types of investments if they are rolled into Qualified Opportunity Funds. Other changes include an expansion of 529 accounts to cover additional private K-12 school expenses (Title VII, Section 70413), doubling the annual tax exclusion from $10,000 to $20,000. H.R. 1 also creates new “Trump accounts” (Title VII, Section 70204), which offer tax advantages for contributions made to these accounts for children born between January 2025 and December 2028. These are just a few of the significant provisions that lawmakers will decide whether to accept as part of the state’s tax code when considering conformity provisions during the 2026 legislative session.

[30] H.R. 1 creates a new partial deduction of up to $25,000 for taxpayers working in occupations that the U.S. Secretary of Treasury determines have traditionally received tips. This deduction begins to phase out at $150,000 for single filers and $300,000 for married couples filing together and requires a Social Security Number. The deduction expires at the end of 2028. H.R. 1 also creates a new exemption on some income earned from over-time, where tax-payers can deduct the enhanced portion of their overtime pay with a limit of up to $12,500 for single taxpayers or $25,000 for married couples filing together. This deduction also begins to phase out at $150,000 for single filers and $300,000 for married couples filing together and requires a Social Security Number.

[31] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (2025, November).

[32] Henderson, J., and Denson, C. (2025, October 9). Iowa’s Taxpayer Relief Fund can help Georgia taxpayers. Georgia Public Policy Foundation. https://www.georgiapolicy.org/news/iowas-taxpayer-relief-fund-can-help-georgia-taxpayers/

[33] Sostaric, K. (2025, October 16). Federal tax cuts add to Iowa’s revenue decline, causing the state to dig deeper into reserves. Iowa Public Radio. https://www.iowapublicradio.org/state-government-news/2025-10-16/federal-tax-cuts-iowa-state-revenue-decline-reserves

[34] Clayworth, J. (2025, July 7). Iowa’s sinking GDP linked to long-term trends, economists warn. Axios. https://www.axios.com/local/des-moines/2025/07/07/iowa-economy-gdp-economic-decline-agriculture; Murphy, E. (2025, July 2). Iowa’s economy had the worst growth in the nation early this year. Why? The Gazette. https://www.thegazette.com/economy/iowas-economy-had-the-worst-growth-in-the-nation-early-this-year-why/#

[35] Office of Governor Brian Kemp. (2025, September 24). Gov. Kemp: Georgia no. 1 for business for 12th straight year. https://gov.georgia.gov/press-releases/2025-09-24/gov-kemp-georgia-no-1-business-12th-straight-year

[36] Fiscal Research Center of the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University. (2025, May). Georgia Tax Expenditure Report for FY 2026 *Revised. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/tax-expenditure-reports/fy-2026-tax-expenditure-report/download

[37] Kanell, M. E. (2024, April 16). When it comes to relocations, Georgia gets more than it gives. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/georgia-news/when-it-comes-to-relocations-georgia-gets-more-than-it-gives/ZKFFORGDY5FCJFDYQYO5FI3OWE/; Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, May 29). Productivity by state – 2024. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/prin4.pdf

[38] Davis, A. (2022, November 16). State child tax credits and child poverty: A 50-state analysis. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/state-child-tax-credits-and-child-poverty-50-state-analysis/