written by Alex Camardelle, Senior Policy Analyst and Jennifer Lee, Policy Analyst

Overview

A parent’s educational level can be a strong predictor of their child’s own educational success and economic outcomes. Parents with higher levels of education also have higher earnings and are more likely to be employed in family-supporting careers.

These educational and economic benefits have a ripple effect that is passed on to their children for generations, and two-generation (two-gen) policies and programs—those that help both parents and their children simultaneously—can help families move up the economic ladder by integrating parent-focused education with high-quality and affordable child care. In fact, implementing and scaling two-generation policies and programs for student parents remains one of the largest underutilized approaches to helping low-income families reach economic security.

Georgia has much to gain from such policies and programs given that the state has:

- 170,000 families where no parent has any postsecondary credentials[1]

- 80,000 families with children where no parent has at least a high school diploma or GED[2]

- More than 500,000 children living in families where the parent lacks secure employment[3]

- Low rankings when compared to other states’ economic well-being and outcomes for children and families[4]

These data demonstrate that intergenerational economic mobility of Georgia’s young children largely depends on policy solutions that remove barriers that prevent their parents from gaining the credentials needed to secure meaningful careers.

Policy Recommendations

- Braid federal and state funding streams to accelerate two-generation policies & programs in Georgia

- Increase state funds for Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) child care scholarships

- Make pursuit of a bachelor’s degree count to qualify for child care assistance

- Provide needs-based scholarships to students with low incomes who are parenting

- Leverage philanthropy to fill in where state policy now lacks

- Improve higher education data collection on students with caretaking responsibilities

More Than One in Five College Students Are Parents

Nationally, more than one in five college students are parents. Public two-year colleges enroll the largest share of student parents in the U.S. (46 percent), and 35 percent attend public and private four-year colleges. For-profit colleges enroll 18 percent of student parents. The remaining 10 percent attend another type or more than one school. [5]

Nationally, more than one in five college students are parents. Public two-year colleges enroll the largest share of student parents in the U.S. (46 percent), and 35 percent attend public and private four-year colleges. For-profit colleges enroll 18 percent of student parents. The remaining 10 percent attend another type or more than one school. [5]

Most student parents are women, and student parents tend to be older. A slight majority have children younger than six. One in five white college students in the U.S. are parents, as are one in five Latino college students and one in three Black college students.[6]

Though state-specific data are not available, regional data on the Southeast show similar numbers to national averages, with slightly higher shares of college students who are parenting.[7]

Student Parents Earn Better Grades, Yet Have Lower Graduation Rates, More Financial Challenges

Though many student parents enroll in college, the added responsibility of caring for children makes it more challenging to complete a credential. Graduation rates for student parents are lower than for non-parenting students. These rates are even lower for single parents. Most student parents lack extra financial resources. Most work, but single parents have higher levels of unmet financial need than their peers and hold more student debt. [8] Despite these challenges, student parents earn higher grades in general. One-third of student parents have a 3.5 GPA or higher.[9]

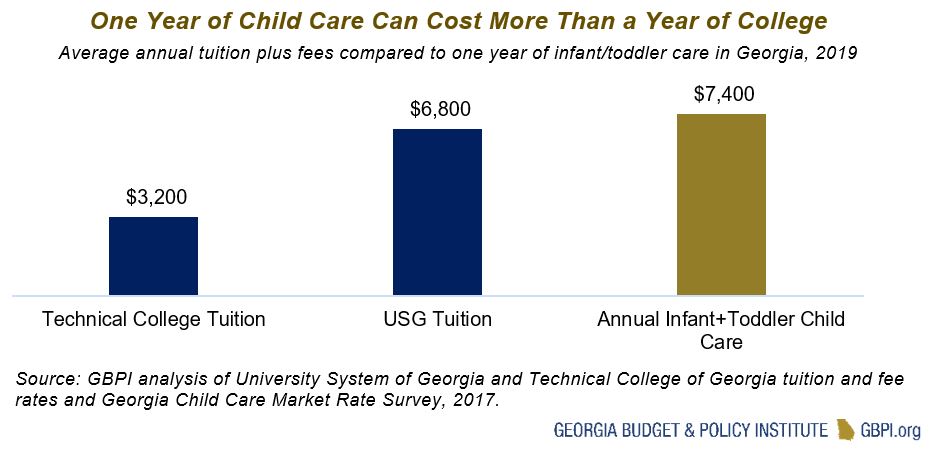

Lack of access to affordable child care remains a constant barrier for student parents. Child care costs can consume a significant portion of the household budget. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), child care is affordable if it costs no more than 7 percent of a family’s income. By this standard, only 16.8 percent of Georgia families can afford infant care.[10] What’s more, for college students, the annual cost of child care can exceed tuition and fees at most of Georgia’s public colleges and universities.[11]

For example, for students attending any of Georgia’s two-year colleges, the costs of child care are extreme when compared to tuition costs. The Technical College System estimates that standard tuition plus fees at all its colleges is $3,200, annually. The median cost of child care ranges between $6,000 and $10,000, depending on the child care center’s location. No matter where you attend a technical college in the state of Georgia, child care can cost up to three times more than tuition and fees.[12]

For Georgia’s four-year public colleges and universities, tuition and fees are less uniform across the university system. But the annual cost of infant and toddler child care for students attending Georgia’s four-year schools exceeds annual tuition and fees at many schools.[13]

Given the extreme cost of child care in Georgia, it is nearly impossible to afford both an education and child care without student aid and child care assistance. As a result, students often have to find jobs with hours that make it difficult to manage full-time caregiving and school. Moreover, the jobs that they take on while in school often pay low wages. When employment is driven by unreliable scheduling and often few hours, it becomes nearly impossible for working student parents to plan for child care, graduate on time or finish a degree.[14]

Limited Data Available on Student Parents in Georgia’s University and Technical College Systems

Georgia’s larger public higher education system, the University System of Georgia, has not tracked or reported numbers on student parents, though individual colleges can. When students apply for federal financial aid through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), they report the number of children they care for, as well as the number of dependents, who can be children.

The Technical College System of Georgia counted 9,802 students as single parents in Academic Year 2019.[15] No data exists on married students with dependents.

Genesis Appiah, 32, is a student at Clayton State University and aspires to be a school psychologist. Her daughter is four years old.

This is not the first time Genesis has been in college, but it is the first time she is in school as a parent. She says, “Being a single mom, it was more important for me to finish college than when I started at 18.” And while her daughter provided motivation, paying for child care is also a challenge.

Genesis qualified for Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) to help pay for child care while enrolled in a dental hygiene program at Atlanta Technical College. But when she transferred to Clayton State University to pursue a bachelor’s degree, she lost her CAPS eligibility. “It made me feel defeated,” she says. A lack of child care sometimes contributed to her missing class. Most days Genesis would wake up at 4:30 a.m. to drive an hour and half to drop off her daughter with her father, drive an hour to class and then drive back to pick up her daughter.

“It was a strain,” she says. “It almost made me quit.” During this time, she found Quality Care for Children’s Boost Child Care Initiative, which provides child care scholarships for students with children under four years old. Without support through Boost, Genesis says she would have been forced to leave school.

Why Two-Gen? Access to Postsecondary Education Improves Economic Security for Single Parents & Children

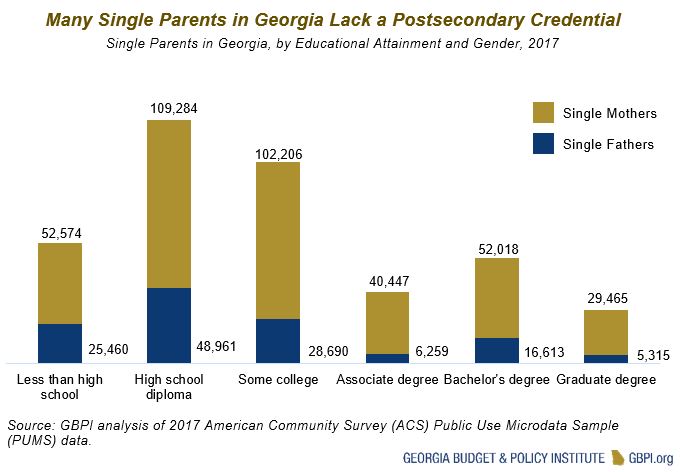

Though both married and single parents need child care, single parents are more likely to experience financial stress and lack a postsecondary credential. In Georgia, only 29 percent of single parents age 25 or above have an associate, bachelor’s or graduate degree, compared to 40 percent of all adults in the same age range.[16]

Although there are single fathers, it is more common for women to be single and parenting. Georgia is home to about 386,000 single mothers 25 or older, and 132,000 single fathers in the same age range. About 172,000 single parents in Georgia over the age of 25 have a high school diploma or less; 109,000 have attended some college, and 132,000 have an associate degree or above. Educational attainment rates are higher for single mothers than single fathers. Thirty-two percent of single mothers have an associate degree or above, compared to 22 percent of single fathers.

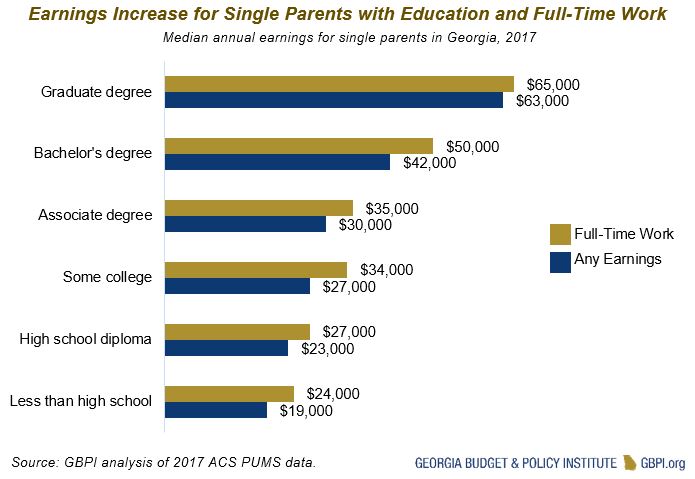

Higher levels of education are associated with greater job opportunities and higher incomes. A single parent working full time earns a median income of $50,000 with a bachelor’s degree, $35,000 with an associate degree or $27,000 for a high school diploma.

Considering all single parents with earnings, including those not working full time, single parents with a high school diploma earn a median income of $23,000, while those with a bachelor’s degree earned $42,000.[17]

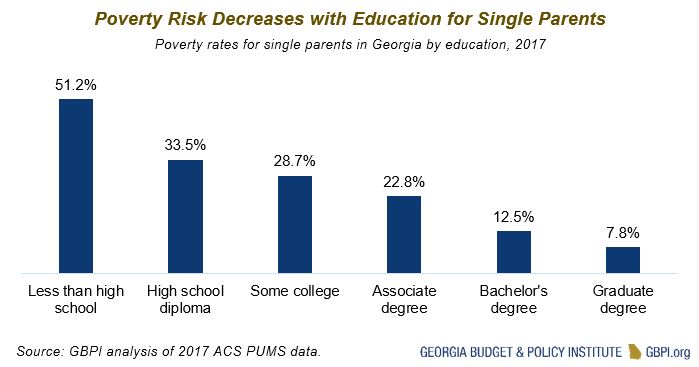

Single parents without postsecondary education credentials are vulnerable to poverty. Half of single parents with less than a high school diploma live below the poverty line. For a single parent with one child, that means earning less than $16,910 a year. Sixty-one percent of single mothers without a high school diploma live in poverty. Though still high, poverty rates are reduced dramatically with higher education levels. In fact, poverty rates for single parents with associate degrees are half the rate for those with less than a high school degree.[18]

Examples of Current Two-Generation Efforts in Georgia

Two-Generation Innovation Grants at the Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning (DECAL)

In 2019, DECAL stepped up its efforts to apply two-generation strategies and policies in the state. Using federal Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) dollars, the agency awarded grants to three technical colleges and one county child care program to support the development of two-generation programs for low-income students. DECAL has also trained frontline staff to strengthen service delivery specifically for students in Georgia’s technical colleges.

Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS) in Georgia

Federal CCAMPIS funding was first authorized in 1998 in an amendment to the Higher Education Act of 1965. The goal of funding for the program is to support institutions in the design and implementation of campus-based child care options for low-income student parents. Currently, Georgia Central Technical College is the only institution in Georgia that received CCAMPIS funding. They are using the funds to provide child care subsidies to Pell-eligible students that are ineligible for state child care subsidies offered through DECAL.

BOOST

The Boost Program: Making College Possible, a privately-funded initiative of Quality Care for Children, provides child care and tuition assistance for low-income college students with young children. It is now in place at Armstrong State, Clayton State and Columbus State.

Nana Grants

Participants in Georgia’s Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) subsidy program are often required to pay a small portion of the cost for care, up to seven percent of their income in what is referred to as a family co-pay. The nonprofit Nana Grants entered into a contractual agreement with the state CAPS program to pay for child care co-pays up to $50 for single mothers attending four technical colleges: Chattahoochee Tech, Gwinnett Tech, Atlanta Tech and Central Georgia Tech.

Maria Palacios, 30, worked in quality assurance and safety at a poultry plant in Gainesville. After the plant made layoffs, she realized that without a bachelor’s degree she was vulnerable to job loss. She also had a young daughter, which motivated her to return to college and find more career security and opportunities.

Maria had started college earlier but left for financial reasons. She scheduled evening classes, worked around her job and relied on a family friend for child care. “It definitely wasn’t financially sustainable,” she says. She even liquidated her retirement savings to help pay for expenses.

A friend told her she could be eligible for financial assistance through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, or WIOA. WIOA paid for about half her child care costs. Without child care assistance, she says, “I would definitely have gone into debt sooner… it would probably be twice what it is now.”

Maria graduated in 2016 from the University of North Georgia with a Bachelor of Business Administration in Finance. She is currently the deputy director of the non-profit organization Georgia Shift and works with young people in leadership development and civic education.

Single Parents Who Are Women, People of Color or Parents of Young Children are More Likely to Face Financial Challenges

Gender, race and child’s age affect single parents’ financial security in different ways. For women and people of color, educational attainment is particularly important. Women tend to earn less than men with similar education credentials, and single mothers are no exception. In Georgia, single fathers’ median income is $40,000. For single mothers, it is $35,000. Poverty rates for single mothers with a high school diploma (40 percent) are double that for single fathers with a high school diploma (20 percent).[19] Women are more likely to face pay and hiring discrimination and occupational segregation into low-wage work. Greater responsibility for unpaid caregiving also acts as a barrier to increased earnings.[20]

Among single parents, Blacks and Latinos are more vulnerable to poverty. Hiring and pay discrimination are well-documented barriers to good-paying jobs, as well as long-term effects of criminal justice system involvement that disproportionately touches people of color.[21] Twenty-four percent of single parents who are white live below the poverty line, compared to 31 percent of single parents who are Black and 42 percent of single parents who are Latino. Higher poverty rates are connected, in part, to lower postsecondary attainment rates. Forty-two percent of single parents who are white have a high school diploma or less, compared to 43 percent of single parents who are Black and 71 percent of single parents who are Latino.[22] Low-income parents without postsecondary credentials find themselves stuck. Without financial assistance, they cannot care for their families and pay for the college education and training that will help them increase their earnings.

Last, poverty rates are 10 percentage points higher for single parents with children younger than six in the household, compared to single parents with older children. Parents with young children are not able to work full-time if they lack access to child care, and child care is also more expensive for children before pre-school age.

Recommendations

There is no shortage of research that supports two-gen strategies as a means to accelerate access to economic opportunity for families with low incomes. These strategies are particularly vital for low-income student parents and their children who already face the combined high costs of child care and postsecondary education. By building on existing investments in two-generation approaches and making a few tweaks to existing state policies, policymakers can remove a major hurdle to economic mobility for a large number of Georgians.

Braid federal and state funding streams to accelerate two-generation policies & programs in Georgia

Low-income student parents that are participating in federally-funded Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) programs can access support from multiple programs, depending on their eligibility. Georgia’s WIOA funds can be used to cover the cost of certificate, diploma and degree programs in high-demand career fields. These costs include tuition and fees, books, transportation and child care. However, WIOA funds for supportive services such as child care assistance are limited on a first-come, first-serve basis, and in many cases they may run out quickly. This is when braided funding can play a powerful role in closing gaps in career pathways for student parents at various levels of their education.

Braiding state and federal funding streams means using funds from across multiple programs to support common services. For example, parents that use child care assistance through CAPS may also be using WIOA funds to pay for the tuition and fees for a certificate or degree program. However, current law only allows participants seeking up to a two-year degree to remain eligible for CAPS, which results in a loss of assistance when the parent decides to pursue education beyond the two-year degree. To help avoid this sudden loss of support, which is often referred to as a “benefits cliff,” federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds could be used to bridge the loss in child care subsidies when a student parent decides to continue their education and pursue a four-year degree.

Georgia can also maximize its investment in state-based financial aid programs by braiding federal TANF dollars and the HOPE Career Grant to provide child care assistance for low-income parents. The HOPE Career Grant is a state financial aid award designed to help students secure technical college credentials. It is available to students working toward a technical college certificate or diploma who qualify for the HOPE Grant and enroll in majors identified as strategically important to the state’s growth.

Increase state funds for Child and Parent Services child care scholarships

To date, the low amount of state funding available for the CAPS program limits access to many student parents who struggle to find affordable child care. Under the current funding levels, DECAL can only serve roughly 50,000 children annually in CAPS, which is only a fraction of the 364,000 children in families with low incomes that potentially need quality and affordable child care. This also includes families led by student parents. Permanently raising the state funding levels for CAPS is a crucial, two-generation investment that will allow a greater number of Georgia’s low-income families to move up the economic ladder and out of poverty.

Make pursuit of a bachelor’s degree count for child care assistance

Georgia is one of only 10 states where pursuit of a bachelor’s degree makes student parents ineligible for state-funded child care assistance. This rule threatens the future earning potential and financial security of families. Research demonstrates the link between greater educational attainment, lifetime earnings and multigenerational benefits.

If a parent currently decides to pursue a bachelor’s degree to move up the economic ladder, they become ineligible for child care assistance. Georgia should allow parents who are currently receiving child care assistance to maintain assistance if they choose to pursue a four-year degree.

Provide more needs-based scholarships to students who are parenting

Though Georgia’s HOPE scholarships and grants are among the country’s most generous, Georgia is one of only two states without a robust scholarship for students with demonstrated financial need. National data indicate that student parents have high financial need and debt, while earning better grades. The state currently funds $26 million in loans with lottery dollars. The state can repurpose some funds for a scholarship that would help students with financial need, including student parents.

Philanthropy can fill in where state policy now lacks

The need for financial assistance for child care far outstrips currently available state funds. To fill this gap, efforts such as Quality Care for Children’s BOOST child care initiative and Nana Grants provide child care scholarships for parents so that they can go to school. Expanding or scaling programs can bolster students and minimize barriers to completion for a host of families.

Improve data collection on students with caretaking responsibilities

Policymakers lack basic information on the number of college students who are parenting or caring for other relatives within the university system and technical college system. Public higher education systems should collect information on students who care for dependents, along with their degree programs and outcome indicators such as persistence and graduation rates.

Conclusion

Two-generation policies and programs—those that serve to enrich the lives of the child and the parent together—are crucial for the long-term economic success of Georgia families. The lack of affordable child care in the state is a massive barrier to completing postsecondary education for far too many. A few tweaks to existing state policy can help remove this barrier.

Endnotes

[1] Working Poor Families Project, Analysis of American Community Survey, 2017 (Washington, D.C: Population Reference Bureau).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The Annie E. Casey Foundation, KIDS COUNT Data Center, https://datacenter.kidscount.org

[5] Cruse, L., et. Al. (2019, April 11). Parents in college by the numbers. Institute for Women’s Policy Research and The Aspen Institute. https://iwpr.org/publications/parents-college-numbers/

[6] Cruse, L., et. Al. (2019, April 11). Parents in college by the numbers. Institute for Women’s Policy Research and The Aspen Institute. https://iwpr.org/publications/parents-college-numbers/

[7] Noll, E., Reichlin, L., & Gault, B. (2017, Jan 30). College students with children: National and regional profiles. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. The Southeast is defined as Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. https://iwpr.org/publications/college-students-children-national-regional-profiles/

[8] Kruvelis, M., Reichlin Cruse, L., & Gault, B. (2017). Single mothers in college: Growing enrollment, financial challenges and the benefits of attainment. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. https://iwpr.org/publications/single-mothers-college-growing-enrollment-financial-challenges-benefits-attainment/

[9] Cruse, L., et. Al. (2019, April 11). Parents in college by the numbers. Institute for Women’s Policy Research and The Aspen Institute. https://iwpr.org/publications/parents-college-numbers/

[10] The cost of child care in Georgia (2018). Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/child-care-costs-in-the-united-states/#/GA

[11] GBPI analysis of University System of Georgia and Technical College of Georgia tuition and fee rates and Georgia Child Care Market Rate Survey, 2017

[12] GBPI analysis of Technical College of Georgia tuition and fee rates and Georgia Child Care Market Rate Survey, 2017.

[13] GBPI analysis of University System of Georgia tuition and fee rates and Georgia Child Care Market Rate Survey, 2017

[14] Spaulding, S., Derrick-Mills, T., & Callan, T. (2016). Supporting parents who work and go to school. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/76796/2000575-supporting-parents-who-work-and-go-to-school-a-portrait-of-low-income-students-who-are-employed.pdf

[15] Data provided by Technical College System of Georgia.

[16] GBPI analysis of 2017 American Community Survey data through IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

[17] GBPI analysis of 2017 ACS PUMS data.

[18] Ibid.

[19] GBPI analysis of 2017 ACS PUMS data.

[20] Blau, F.D., & Kahn, L.M. (2016). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 21913. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21913

[21] Quillian, L., et. al. (Oct 2017). “Hiring Discrimination Against Black Americans Hasn’t Declined in 25 Years,” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/10/hiring-discrimination-against-black-americans-hasnt-declined-in-25-years

[22] GBPI analysis of 2017 ACS PUMS data.