This report was co-authored by Stephen Owens, Ph.D, Senior Policy Analyst & Denae Clowers, Policy Intern

Key Takeaways

- Reliable lottery funding helped grow Georgia’s Pre-K Program in early years, but a change to raise class sizes has endured for a decade.

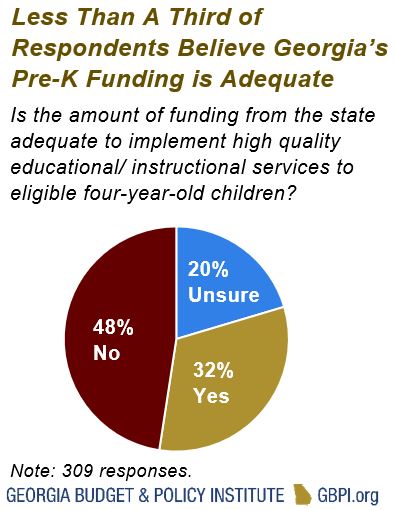

- 48 percent of respondents do not believe the funding provided is adequate to implement high quality pre-K, compared to 32 percent that believe it is sufficient.

- State lawmakers should increase funding for Georgia’s Pre-K Program to raise lead- and assistant-teacher pay and cover some of the costs for capital improvements.

Georgia’s Pre-Kindergarten Program (Georgia’s Pre-K) is one of the first state-funded universal pre-K programs in the nation. The program is offered to all 4-year-olds in the state (making it universal) but contains yearly “caps” on enrollment subject to appropriation. High-quality early learning programs can help students do well in elementary school and have been shown to improve school grades and social-emotional skills for years following.[1] While policymakers in Georgia are rightly concerned with the program’s ability to prepare students for Kindergarten, there is also little available evidence on whether the state is providing an adequate dollar amount to the program to, for instance, increase enrollment. This report summarizes a survey of pre-K program directors on the expenses they incur, their perspectives on the adequacy of state funds to meet student needs and the effects of COVID-19. Based on the findings, this report offers three key recommendations:

- Move lead teachers to the K-12 salary schedule

- Increase pay for assistant teachers

- Add funding for capital improvements

Georgia’s Pre-Kindergarten Primer

Georgia’s Pre-K is available to all children age 4 by September 1 in the state regardless of family income. The program is administered by Bright from the Start: Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning (DECAL). What began as a campaign promise from then-gubernatorial candidate Zell Miller in 1990 has grown into a program that served more than 84,000 children in fiscal year (FY) 2020 alone. Voters passed a referendum in November 1992 to create the Georgia Lottery which has funded the initiative every year except in its pilot phase in FY 1993.[2] Georgia’s Pre-K is a public-private partnership where the state allocates funding to public schools and private providers that have applied to implement the program.

Enrollment

Georgia Policy Labs studied the enrollment of Georgia’s Pre-K from FY 2012 to FY 2019.[3] Over this time Georgia’s Pre-K served children that are more likely to be Black and less likely to be white than the population of the state. Enrollment was evenly split between public schools and private providers. In FY 2019, 47 percent of Georgia’s Pre-K students were in families that received a form of income-based benefit (SNAP, TANF, etc.), but this share had decreased from 58 percent in FY 2012. Taken together, the program grew in share of people of color served while serving fewer children who have received income-based supports. This decrease in income-based benefits is partly attributable to the overall enrollment decline in these programs as economic expansion—that is, people moving into better jobs or earning higher wages—led to fewer people receiving benefits over the timeframe.

Funding

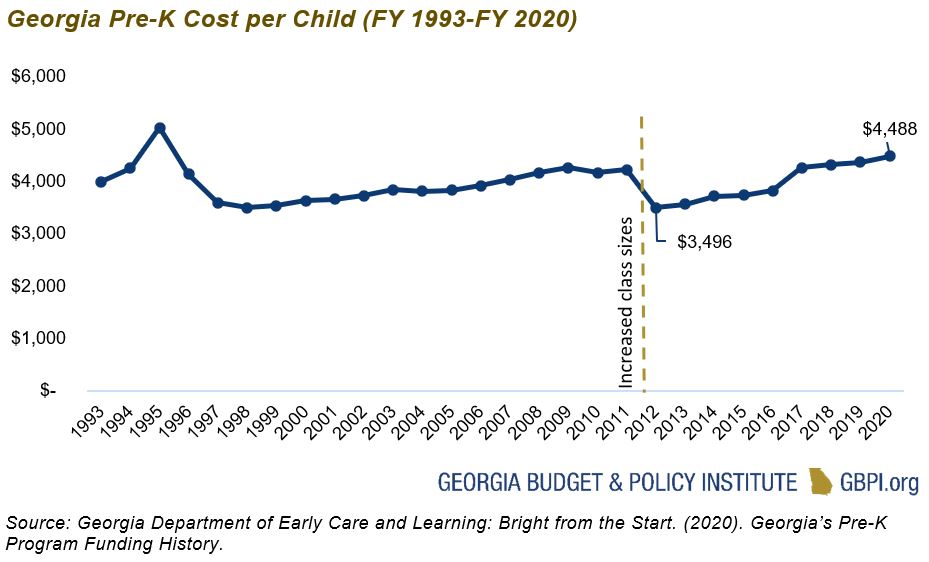

Total funding for the program is determined by the Georgia General Assembly annually. The cost for Georgia’s Pre-K varies based on the number of slots available and the cost of expenses that the state will reimburse grantees for salaries, curriculum, etc. In 1993 Georgia made 750 slots available. This number would increase 100-fold over the next 15 years and then plateau at 84,000 slots from FY 2013 to FY 2020. Georgia’s General Assembly increased the allocation from the lottery proceeds every year from FY 1994 ($3 million) to FY 2011 ($355 million) before two consecutive years of reduced funds. Even as the allocation dropped $55 million in FY 2012 the state added 2,000 pre-K slots by raising the size of classes from 20 to 22 students per lead teacher and shortening the school year by 20 days.[4] The school-year calendar was restored in subsequent years while the class size increase has remained. The graph below shows the change in cost per student since the program’s inception.

Methods

In the winter of 2020, 309 program directors (38 percent of all program directors statewide) responded to a survey on the costs and funding of Georgia’s Pre-Kindergarten Program, as well as how the program might have changed due to the global pandemic. These respondents represent 176 different cities and towns across the state. We have included respondents’ quotes to contextualize specific perspectives. Names have been used with permission.

Findings

Expenses

In the 2020-2021 school year, Georgia’s Pre-K credentialed lead teachers can be paid between $22,000 and $39,000 depending on level of credentials, with additional compensation for creditable years of experience.[5] Pre-K providers are allotted $38,821 for each lead teacher with a four-year college degree and a teaching certificate level 4 (or T4). This base amount is roughly equivalent to a similarly credentialed public K-12 teacher in Georgia’s public schools. The program operating guidelines instruct providers to pay at least 90 percent of this amount, just under $35,000, directly to the employee. Based on approximately 270 responses when asked, the average reported first-year lead teacher salary was $37,000 annually. Respondents reported lead teacher salaries ranging from $26,000 to $53,000. Sixty-six project directors (representing 24 percent of all respondents) reported a salary for a first-year T4-level teacher below the state requirement. These responses may be the result of the lack of a lead-teacher when substitutes would have been used.

In the 2020-2021 school year, Georgia’s Pre-K credentialed lead teachers can be paid between $22,000 and $39,000 depending on level of credentials, with additional compensation for creditable years of experience.[5] Pre-K providers are allotted $38,821 for each lead teacher with a four-year college degree and a teaching certificate level 4 (or T4). This base amount is roughly equivalent to a similarly credentialed public K-12 teacher in Georgia’s public schools. The program operating guidelines instruct providers to pay at least 90 percent of this amount, just under $35,000, directly to the employee. Based on approximately 270 responses when asked, the average reported first-year lead teacher salary was $37,000 annually. Respondents reported lead teacher salaries ranging from $26,000 to $53,000. Sixty-six project directors (representing 24 percent of all respondents) reported a salary for a first-year T4-level teacher below the state requirement. These responses may be the result of the lack of a lead-teacher when substitutes would have been used.

Unlike lead teacher salaries, DECAL apportions a set amount for assistant teachers that does not adjust to credentials or years of experience. Respondents recorded assistant teacher salaries range from $12,000 to $35,000. DECAL requires that assistant teachers be given the full salary provided by the department: $16,190.35 in FY 2021.[6]

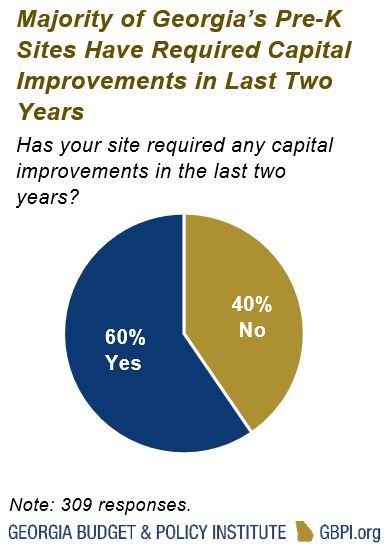

While lead and assistant teacher pay take up the lion’s share of program costs, providers also face capital improvement costs (think roof repair or HVAC replacement) as well as material costs necessary for the operation of their programs. Unlike salaries, Georgia’s Pre-K capital improvements are not “allowable Pre-K expenditures” with allocated lottery funds.[7] Our survey found that in the past two years, 60 percent of providers have required at least one capital improvement.

Adequacy

Several providers are required to rely on funding sources outside of Georgia-allotted funding to support the standard operations of their pre-K programs. More than 60 percent of those surveyed reported providing assistant teachers more compensation or benefits than what is funded by DECAL. To provide additional benefits to assistant teachers, providers report turning to various other sources of funds including local funds and tuition from other child care programs to fill the gap.

Several providers are required to rely on funding sources outside of Georgia-allotted funding to support the standard operations of their pre-K programs. More than 60 percent of those surveyed reported providing assistant teachers more compensation or benefits than what is funded by DECAL. To provide additional benefits to assistant teachers, providers report turning to various other sources of funds including local funds and tuition from other child care programs to fill the gap.

Teacher pay is not the only reason providers seek additional funds. As previously mentioned, most sites surveyed faced capital improvement costs in the past two years. When asked how these costs are covered, many sites again cited daycare and local funds, but providers also reported using the owners’ personal finances and/or taking out loans to fill these gaps. Perhaps as a result, only 32 percent of respondents believe that the funding currently provided to fund pre-K is adequate to implement “high quality instruction.” Respondents frequently cited educator pay, educational materials, and extracurricular options as signs of inadequacy.

A major theme found throughout the comments on adequacy is that recruiting and maintaining pre-K teachers is very difficult when potential teachers could use their certification to teach in a school district where pay is higher.

“In order to attract highly educated individuals to these positions, the amount of state funding for salaries is low. Certified teachers look for positions in public schools in order to get a higher salary, better benefits, as well as payment into [Teachers Retirement System of Georgia]. At a minimum, all lottery funded pre-K teachers should make as much as kindergarten teachers in their district.”

-Cox Pre-K at Drew Charter School (Atlanta, GA)

In addition to teacher salaries, educational materials are also necessary to the successful operation of Georgia’s Pre-K Program. From paper plates to computers, pre-K programs look to provide adequate supplies to ensure their students are receiving a quality education. Many respondents noted that they would like to increase the use of technology in their facilities and their pre-K classrooms, but funding constrains that, leaving centers wanting more from their educational tools.

“Additional funds would level the playing field for Title 1 schools and afford our students the opportunity to interact with more technology.”

-Providence Elementary (Temple, GA)

Educational supplies are not the only resources providers wish they could deliver to students. Various respondents also discussed extracurricular options available to students. DECAL funding does not account for expenses like field trips, which some programs go on, so providers must search for other funds for these expenses. Music, art and physical education options were also mentioned as activities students would ideally be able to participate in if not for budget constraints.

“We had to supplement around $19,000 for teacher salaries and benefits, assistant teacher salaries and benefits, substitute teachers, field trips and supplies. In addition, the cost of utilities, custodial and administration costs are incurred by each school.”

-Monroe School District (Forsyth, GA)

COVID-19

Despite COVID-19 altering the way education is delivered for many people, a large majority (72 percent) of the surveyed pre-K providers offered traditional instruction for the 2020-2021 academic year. Although the method of instruction has not changed for most providers, there have been decreases in enrollment for many. Over 60 percent of the program directors who responded to the survey report having fewer or greatly fewer students for the current school year compared to previous years. Most programs did not see a reduction in funding for the 2020-2021 school year however because DECAL paid full funding for open classes (meaning the department did not prorate payments based on student enrollment).[8] Even these programs may have seen less revenue due to lower enrollment in before- or after-school offerings. Despite so many providers facing decreased numbers of students and potential budgetary pressures, providers appear very optimistic about enrollment, and consequently funding, quickly returning to normal. When asked how sites with decreased enrollment intend to cover the associated funding decline, many providers referenced the coronavirus as the source of their decreased enrollment and stated that the decline should not be long-lasting as the declines are due to current precautions and hesitancy.

“We hope that it will not continue to impact the numbers. We feel that this [will] pass and our numbers for pre-K will increase to normal.”

-Lollipop Kids Inc. (Blackshear, GA)

“We are unsure. Just trying our best to make everything work for the kids. We are hoping with the start of the new year maybe more families will be comfortable with face to face learning. We usually have zero spots and a waiting list. This year we still have two open spots.”

-Program Director (Canton, GA)

“We are purchasing enough supplies so every student can have their own crayons, markers etc. due to COVID. We are having to purchase more PPEs than more than [sic] usual this year… We will help those Pre-K parents who are in out before and after care and unable to cover the [before and after-school] fees due to COVID.”

-Amazing Hearts Child Development Center (Appling, GA)

Recommendations

Those who responded to this survey paint a picture of Georgia’s Pre-K where many teachers leave for higher pay elsewhere and those who remain are underpaid. Further, the lack of funding for capital improvements and new costs tied to the pandemic leave providers searching for money in private tuition (for other programs they offer), personal finances or grants like those offered from Head Start. For this reason, the state should raise the pay for all teachers and include funds for capital improvements.

Many respondents remarked on their frustration with not being able to compete financially to keep beloved teachers. While the pay difference between pre-K and K-12 public teachers causes many qualified employees to leave Georgia’s Pre-K, the pay for assistant teachers is abysmal. With a 190-day commitment and 6.5 hour workdays, the minimum salary for assistant teachers is $13.11 per hour. Even if assistant teachers were able to work 52 weeks a year it would still be less than 175 percent of the Federal Poverty Guidelines ($22,155).[9]

“Teachers need more compensation, a lot of the money coming in is going out on fixed cost such as mortgage, utilities and we have added a new expense to our list: cleaning and sanitizing to maintain all our staff and children’s safety. There is a lot of uncertainty every day, we are trying to do our best to maintain but definitely more funding would make life easier.”

– Castial Academy, LLC (Statham, GA)

Georgia lawmakers should increase assistant teacher pay significantly and place lead pre-K teachers on the same salary schedule that districts use for K-12 teachers. This additional money will help make sure that teachers can remain in the classroom for which their gifts are best suited and reduce the incentive to move into older grades.

Additionally, if the state were to pay for capital improvements, pre-K centers would have less reason to increase tuition on other services. By forcing local providers to shoulder the costs of expenses like air conditioning replacement, it increases the costs elsewhere. So, an inadequate “state-funded” program for 4-year-olds actually raises child care costs for those aged 0 to 3, or takes away from public school funding meant for K-12. Providers must find the funding elsewhere, and these costs will disproportionately affect low-income Georgians.

The decision to not lower funding for pre-K grantees that remained open during the pandemic and had lower enrollment will benefit the program in the long run. In that same spirit, if Georgia can adequately fund pre-K, the benefits will be felt immediately and for years to come. Raising teacher pay and covering the costs of capital improvements will not solve all adequacy issues but will help move the state toward a program that prepares children for Kindergarten, no matter the family’s income.

Acknowledgments

The Georgia Budget and Policy Institute would like to thank the pre-Kindergarten program directors who participated in the survey. Respondents provided extensive data, thoughtful responses and wise feedback. Their attention and effort are greatly appreciated. Site leaders, program directors and educators have our admiration and gratitude for the work they do each day to serve Georgia’s children.

Appendix: Methodology

Dr. Stephen Owens developed the survey instrument. Emmett Allen, who interned with GBPI during the fall of 2020, distributed the survey to the state’s 817 project directors after pivotal support from representatives from DECAL via a link to the survey, which was online. The survey was available from November 3 through December 14, 2020. Mr. Allen subsequently contacted the program directors via phone and email to request their participation over a period of four weeks.

Participation was voluntary. Participating project directors identified a contact person for follow-up information requests. Respondents’ responses were available to all contact persons for their review. GBPI exported a spreadsheet of each of the responses.

GBPI only published the individual names, titles and/or pre-Kindergarten providers after express consent from survey respondents. All other responses have been kept anonymous.

End Notes

[1] Meloy, B., Gardner, M., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Untangling the evidence on preschool effectiveness: Insights for policymakers. Learning Policy Institute. https://edworkingpapers.org/sites/default/files/Untangling_Evidence_Preschool_Effectiveness_REPORT.pdf

[2] Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning. (2021). History of Georgia’s Pre-K program. http://www.decal.ga.gov/Prek/History.aspx

[3] Goldring, T. (2020). Children in Georgia’s Pre-K program: Characteristics and trends, 2011-12 to 2018-19. Georgia Policy Labs. https://gpl.gsu.edu/publications/pre-k-analysis/

[4] Badertscher, N. (2012). Georgia pre-k teachers not expected to rush back as cuts are partially restored. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/local/georgia-pre-teachers-not-expected-rush-back-cuts-are-partially-restored.

[5] Georgia Dept of Early Care and Learning. (2021). Georgia’s Pre-K program 2020-2021 school year pre-K providers’ operating guidelines. http://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/Guidelines.pdf

[6] Georgia Dept of Early Care and Learning. (2021). Georgia’s Pre-K program 2020-2021 school year pre-K providers’ operating guidelines. http://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/Guidelines.pdf

[7] Georgia Dept of Early Care and Learning. (2021). Georgia’s Pre-K program 2020-2021 school year pre-K providers’ operating guidelines. http://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/Guidelines.pdf

[8] Georgia Dept of Early Care and Learning. (2021). Georgia’s Pre-K program 2020-2021 school year pre-K providers’ operating guidelines addendum covid-19 guidance. http://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/PreKProvidersOperatingGuidelinesAddendum.pdf

[9] Georgia Department of Community Health. (2021). Federal poverty guidelines. https://dch.georgia.gov/federal-poverty-guidelines-0![]()