Thank you to Latin American Association & Center for Pan Asian Community Services for translation services

Stephanie Angel contributed to the Legislative History and Legal Obligations sections of this report.

Introduction

The English to Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) program assists students who are learning English in school as an additional language, known as English Learners (ELs), in developing the language skills necessary to meaningfully participate in all aspects of their K-12 education. Georgia public schools educate one of the largest EL populations in the nation. Several key pieces of legislation have cemented the rights of ELs and outlined the obligations that state educational agencies (SEAs) and local school districts must comply with. After a review of the legislative history and legal obligations, this report analyzes Georgia’s ESOL program specifically and the treatment of ELs generally in public schools and finds that students in Georgia’s ESOL program are inhibited by arbitrary spending caps, policies that de-prioritize their home language and underrepresentation in gifted courses. There are, however, budget and policy considerations that can improve the experience of ELs in Georgia’s public schools. To support these students, policymakers should:

- Provide adequate funding to meet the needs of children in ESOL

- Promote programs that treat home languages as an asset

- Eliminate state laws and rules that require English-only standardized tests

- Protect the rights of English learners by including these students in gifted programs

Legislative History of English Language Learning

The enactment of several key pieces of legislation codified the rights of ELs into law, established the obligations and responsibilities held by SEAs and local school districts and ensured additional federal funding for this purpose. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation that paved the way for several societal subgroups, including ELs, to be free from discrimination in public accommodations and federally-funded programs on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Shortly thereafter, Congress enacted the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA), which confirmed that public schools and SEAs must act to overcome language barriers that deny students the opportunity to equally participate in school.[1] The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA) expanded federal funding for primary and secondary education. Subsequent reauthorizations of ESEA included the Bilingual Education Act of 1968 which recognized the unique needs of ELs and provided additional funds to ensure those needs would be met. Notably, Georgia lawmakers did not codify the obligation to provide English language instruction in state law until 1981.[2]

Legal Obligations for English Language Learning

Along with the civil rights protections established by federal law, litigation has been used as a tool to enforce compliance by SEAs and local school districts. In the 1974 case of Lau v. Nichols, a school district with 2,856 students of Chinese ancestry who did not speak English provided supplemental English language courses to only 1,000 of those students. The U.S. Supreme Court confirmed that public schools must take “affirmative steps” to overcome the language barriers of all ELs because failing to do so denies them a meaningful opportunity to participate in public educational programs in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[3]

The U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice hold the authority to enforce civil rights laws in the educational context and as such, provided guidance to SEAs and public schools in 2015 to address common compliance issues in meeting their federal obligations to ELs. Some of the shared obligations include the timely, valid and reliable identification and assessment of EL students, the provision of sufficient staff and support for language assistance programs, the avoidance of unnecessary segregation between EL students and native English-speaking students, and meaningful communication with limited English proficient parents in a language they can understand.[4]

English for Speakers of Other Languages in Georgia

Enrollment

Quick Facts

- Georgia educates the eighth-highest number of ELs in the nation (FY 2017).[5]

- 108,752 total students in ESOL in Georgia (FY 2019).[6]

- EL enrollment in ESOL grew by 61 percent from FY 2011 to FY 2019.[7]

- Spanish is the most common home language for ELs (78 percent), followed by Vietnamese, Chinese and Arabic.[8]

Georgia’s ESOL program has grown considerably over the last decade. Of the seven states with more ELs than Georgia, only one grew at a faster rate from FY 2000 to FY 2017. Georgia’s EL enrollment growth was 3.5 times faster than the national average over the same time.[9]

ESOL enrollment is highest in school districts in the metro Atlanta area. Below is a table of all the school districts in Georgia with greater than 2,000 students in ESOL in FY 2019.

Statewide, 6.3 percent of the total student population is in the ESOL program.[10] In FY 2019, 23 school districts (and several state-authorized charter schools) did not contain a single student in ESOL.[11]

Gifted English Learners

In FY 2019, 11.6 percent of Georgia public school students participated in gifted courses. That same year only 1.2 percent of students in the ESOL program also took a gifted class. Among school districts in Georgia with ten or more students in ESOL, 69 traditional school districts and five state-authorized charter schools had zero children in the gifted program that were also in ESOL.[12] It should be noted that there is no evidence of any correlation between home language and intelligence.

Program

Georgia’s ESOL program operates under several federal and state laws as well as State Board of Education rules and local district decisions. According to the Georgia Department of Education’s resource guide for the program:

The purpose of the ESOL language program is to provide English language development instruction and language support services to identified K-12 English Learners (ELs) in Georgia’s public-school system for the purpose of increasing their English language proficiency and subsequently their academic achievement.[13]

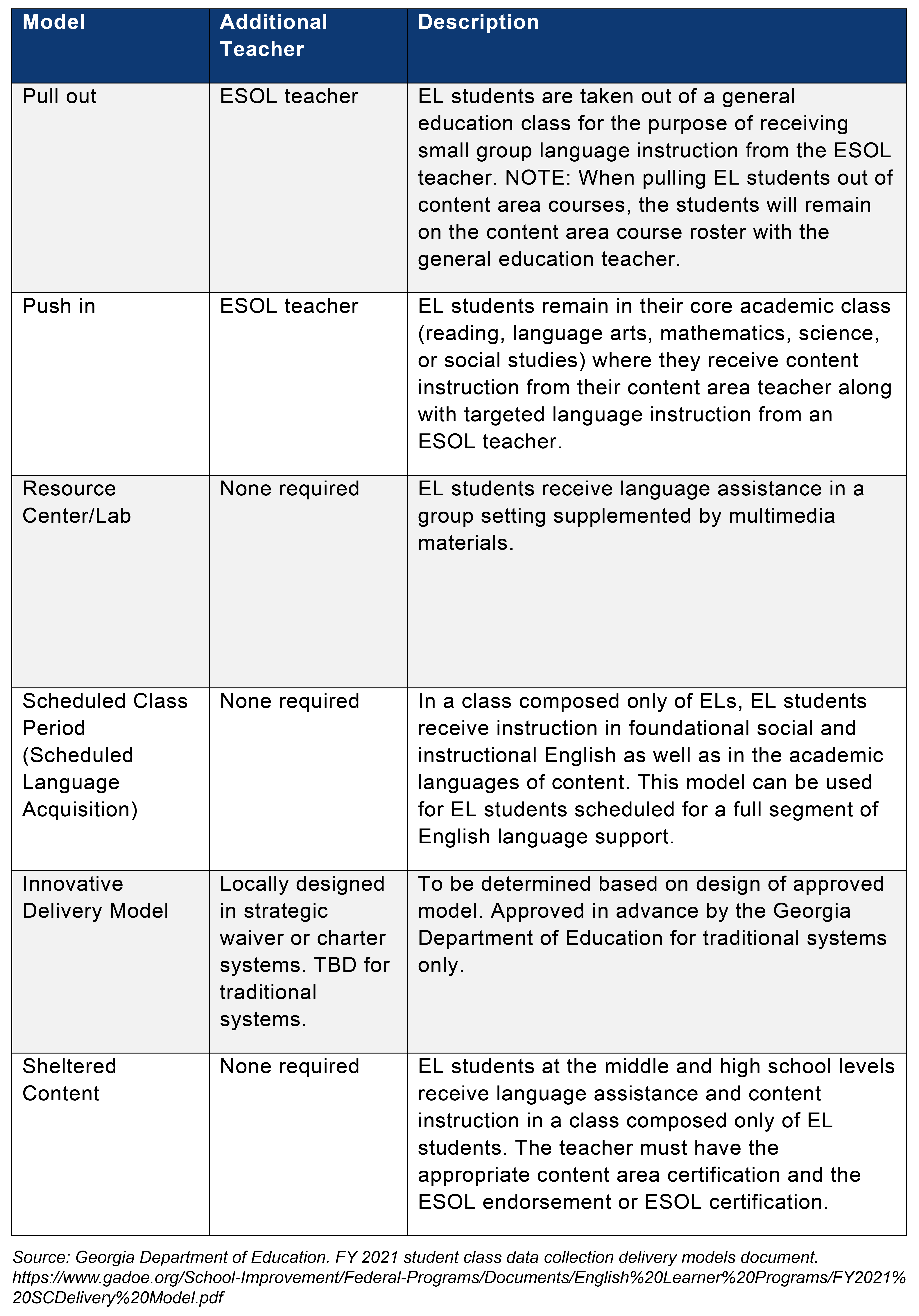

Students identified for ESOL are offered several different models for program delivery based on school district decisions and the needs of the child. The “pull-out” model entails EL students being removed from the general education environment in order to receive small-group language instruction from a dedicated ESOL instructor. The “push-in” model, by comparison, has the student remaining in the core academic class where they receive target language instruction from an ESOL teacher while simultaneously receiving academic instruction from a content-specific instructor. School districts also can place ESOL students in a computer lab or create an approved “innovative delivery model” for instruction, among other delivery methods. A full list and description of models can be found in the appendix.

Roughly one-third (32 percent) of students in ESOL statewide participated in the program via the push-in model in FY 2019. That same year school districts placed 40.3 percent of ESOL students in EL-only settings (delivery models “pull out,” “scheduled class period” and “sheltered content” in the appendix). Twenty-five percent of ESOL students received language instruction through an innovative delivery model, but this figure is overwhelmingly weighted by the fact that the state’s largest school district, Gwinnett County Public Schools, uses this model almost exclusively. In FY 2019, 79 percent of the students in this delivery model were taught in Gwinnett. The remaining 2.7 percent of children receive ESOL through resource labs or dual-language immersion.[14]

Some Programs Subtract Knowledge of Home Language

Often any instruction of the home language ceases the moment a child enters ESOL. If students are only taught English in school, the new language acquisition can replace or de-prioritize the home language and culture. This internal replacement can be known as subtractive bilingualism.[15] Research has shown that programs that view the home language as an asset to be invested in, as opposed to a liability to overcome, can produce academic and social-emotional improvements.[16]

By the same token, Georgia is one of 19 states that does not provide state-standardized assessments in any language other than English.[17] Only two other states in the nation with a larger number of ELs than Georgia have English-only state assessments. For several years federal law has allowed states to provide these tests in students’ home languages because it is impossible to measure knowledge in a language that a child is not fluent in.

Funding for ESOL in Georgia

Funding for ESOL is provided within the Quality Basic Education Act, which dictates the majority of state funding for public education in Georgia. School districts are allotted the funds to pay for one ESOL teacher for every seven “full-time” students in the program. In FY 2021 this calculation amounts to $7,178 per full-time equivalent (FTE) student in the ESOL program for direct instructional costs.[18] As a comparison, full-time kindergarten students are allotted $4,638 and full-time twelfth-grade students are allotted $2,775 per student for the same function.[19] This ESOL dollar amount is misleading, however, as no student can receive state funding to participate in the ESOL program for the entire school day. According to Georgia State Board of Education rule, students in grades kindergarten through third grade can only be provided state funding for one-sixth of a school day in ESOL (one class or “segment” per school day), for example.[20] It would require 42 kindergarten students in ESOL to earn the allotment for one ESOL teacher. A table showing the maximum state-funded ESOL program segments allowed per grade and the subsequent funding amount is below.

Depending on the grade level, Georgia’s funding weight is either middle-of-the-road compared to other states (for K-8 students) or noticeably higher than the national average (for 9-12 students receiving the maximum amount of state funding).[21] For example, Tennessee funds ELs at a student-teacher ratio of 30:1 but also provides funding for an interpreter for every 300 ELs.[22] North Carolina allots funding for a 20:1 ratio but changes the funding based on high or low concentrations of ELs.[23] Direct state funding comparisons are complicated by the fact that states have different entrance and exit criteria for ESOL as well as caps for funding.

Difference Between Funding and Expenditures

School districts in Georgia enjoy wide flexibility on how to spend most state dollars. The state’s ESOL programs “earned” enough state funding for just under 3,500 ESOL teacher positions in FY 2020.[24] However, according to the best data available, school districts employed between 2,600 and 2,900 ESOL teachers that school year.[25] The way Georgia reports school district expenditures makes it nearly impossible to track how the funding for the remaining teachers is spent at the school level. State law and Georgia State Board of Education rules allow for this funding to address student needs in other ways (e.g. ESOL curriculum, online resources) or to enter into the equivalent of the school’s general operating budget. ESOL programs are not unique in this difference between what is allotted and how funds are spent. Other school programs such as gifted education show a large difference between the number of teachers “paid for” in state funding and the actual number employed in Georgia schools.[26] The combination of state funding caps and the allocation of resources at the school level produced a teacher-to-student ratio of one dedicated ESOL instructor for over 39 children in ESOL in the state of Georgia in FY 2019.[27]

Budget and Policy Considerations

What follows are considerations for what would need to happen in order for Georgia to better realize the potential of a growing number of children in the state.

Provide adequate funding to meet the needs of children in ESOL

While Georgia’s funding weight might be high for certain student groups, a weight is only as good as the base funding amount. Since Georgia’s overall school funding amount is low nationally, a “high” weight for ESOL can only do so much. In FY 2016 Massachusetts provided only 7 percent more per EL in high school, but this amount is $2,900 more per student than what a similarly-situated EL in Georgia would receive in FY 2021.[28] What is absent in almost every state’s funding model is an attachment to evidence.

Georgia’s funding mechanism appears to use best practices by differentiating based on grade level, but the enrollment cap for children in kindergarten through eighth grade needs review.[29] This fact is supported when considering that on the National Assessment for Education Progress (NAEP) only 3 percent of ELs in Georgia scored proficient in eighth-grade reading while 30 percent of non-ELs scored the same.[30] Results like these without a study for the true cost of educating these children make plain that the funding caps have no discernable purpose in modern-day schooling in Georgia.

On Teacher Shortages

The difference between the state funding allotted for ESOL and the true number of teachers statewide can be viewed a variety of ways. On the one hand, these staffing decisions could be seen as a redirection of funds meant for students who need, and are entitled to by law, intensive educational services. The history of public education in Georgia is filled with discrimination of students based on a litany of factors. Further, in October 2020 there were three current federal cases under investigation for discrimination against English learners in the state.[31] Any argument that ELs are not receiving the resources they need to have equal opportunities would be backed up by history, current litigation and student test scores.

Another view on the staffing differential in ESOL is that this analysis shows the consequences of underfunding public education for the better part of a generation. Georgia’s public schools have been underfunded by $10.2 billion since FY 2003, with the General Assembly meeting the bare minimum of “fully funding” schools only twice over that period.[32] On top of austerity cuts, several costs of mandatory functions of the school have increased with no subsequent increase of state dollars. For example, state money for student transportation has been practically unchanged since FY 2000 while the cost to the districts has increased $612 million.[33] To meet the needs that the state does not account for, school leaders are forced to pull money from wherever it is available, and ESOL is one of many programs that face the repercussions of underfunding.

Georgia lawmakers must adequately fund public education writ large. Until then, school leaders will continue to be left with more needs than money.

Promote programs that treat home languages as an asset

The subtractive bilingualism that Georgia participates in ignores and devalues an integral part of a child. Curriculum and delivery methods exist that can treat the home language as a valuable asset to be invested in instead of a liability a child must overcome to participate in the school.[34] Methods such as dual-language immersion (where students are taught half the day in English and the second half of the day in another language) have shown to accelerate a child’s educational development compared to English-only instruction.[35] This policy consideration is related to funding because schools that do not have truly bilingual staff would need to hire additional instructors to teach the non-English portion of the school day. Georgia has already started to recognize the value of knowing more than one language: in 2016 state lawmakers created a Seal of Biliteracy for high school diplomas via HB 879 for students who, in addition to speaking English, show proficiency in one additional language. Similarly, the state’s Dual Language Immersion program has grown since its inception in 2015.[36] Treating ESOL instruction with the same sentiment would continue the work to recognize the value in a child’s first language.

Eliminate state laws and rules that require English-only standardized tests

By relying on a subtractive model and English-only assessments, Georgia hurts children while reaping no tangible benefit. Several districts provide language accommodations on tests for students throughout the school year, but this same assistance is not allowed when it comes to the Georgia Milestones, the state’s standardized assessments. Testing students in a language other than their home language causes the dual harm of discouraging children who might otherwise be learning a great deal and withholding information from the state on the performance of these students.

Protect the rights of English Learners by including these students in gifted programs

The United States Department of Justice enforces discrimination claims of ELs under the previously-mentioned Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA) of 1974. One example of a violation of the EEOA is if a school district or state agency “excludes [EL] students from gifted and talented programs based on their limited English proficiency.”[37] The fact that there were only 3,313 ELs in gifted programs in FY 2019 is at best a glaring missed opportunity and at worst the foundation for a civil rights investigation.[38] Policymakers would be wise to address the lack of representation in gifted programs for these children individually and so that our state can best invest in the potential of all its citizens.

Appendix: Georgia Department of Education ESOL Delivery Models and Description

Endnotes

[1] The Office for Civil Rights at the United State Department of Education and the Civil Rights Division at the U.S. Department of Justice. Dear Colleague letter: English learner students and limited English proficient parents. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-el-201501.pdf

[2] O.G.C.A. §20-2-156.

[3] Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974)

[4] The Office for Civil Rights at the United State Department of Education and the Civil Rights Division at the U.S. Department of Justice. Dear Colleague letter: English learner students and limited English proficient parents. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-el-201501.pdf

[5] National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). English language learner (ELL) students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by state: Selected years, fall 2000 through fall 2017. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_204.20.asp

[6] Governors Office of Student Achievement. (2019). Student enrollment data. https://gosa.georgia.gov/report-card-dashboards-data/downloadable-data

[7] GBPI analysis of Governors Office of Student Achievement Student Enrollment Data, FY 2011 and FY 2019. https://gosa.georgia.gov/report-card-dashboards-data/downloadable-data

[8] U.S. Department of Education. (2017). Consolidated state performance report: Parts I and II for state formula grant programs under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act As amended in 2001 for reporting on School Year 2015-16. Georgia. https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/account/consolidated/sy15-16part1/ga.pdf

[9] GBPI analysis of National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). English language learner (ELL) students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by state: Selected years, fall 2000 through fall 2017.

[10] Governors Office of Student Achievement. (2019). Student enrollment data. https://gosa.georgia.gov/report-card-dashboards-data/downloadable-data

[11] Ibid.

[12] Based on a GBPI analysis of Georgia Department of Education. (2019). English learner (EL) students in gifted courses, by EL status/monitoring level, system and state level school year 2018-19 student class data collection system, end of year signoff cycle (SC 2019-L)

[13] Georgia Department of Education. (2020). A resource guide to support school districts’ English learner language programs. (p. 3). https://www.gadoe.org/School-Improvement/Federal-Programs/Documents/English%20Learner%20Programs/EL%20Language%20Programs%20-%20State%20Guidance%20Updated%2027%20Sept%202020.pdf

[14] Based on a GBPI analysis of Georgia Department of Education. (2019). ESOL delivery model – counts of ESOL-served students (EL=Y and ESOL=Y) by delivery model, system and state level school year 2018-19 student class data collection system, end of year signoff cycle (SC 2019-L).

[15] Fédération des parents francophones de Colombie-Britannique. bilingualism – types of bilingualism. http://developpement-langagier.fpfcb.bc.ca/en/bilingualism-types-bilingualism#:~:text=Subtractive%20bilingualism%20refers%20to%20the,language%20is%20a%20minority%20language

[16] For a review of the literature on additive multilingual education, see Bauer, E. B. (2009). Informed additive literacy instruction for ELLs. The Reading Teacher, 62(5), 446-448.

[17] Tabaku, L., Carbuccia-Abbott, M., & Saavedra, E. (2018). Midwest Comprehensive Center review: State assessments in languages other than English. Preliminary report. Midwest Comprehensive Center. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED590178.pdf

[18] Georgia Department of Education. (2020). Weights for FTE funding formula; FY 2021.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Georgia State Board of Education. (2017). 160-4-5-.02 Language assistance: Program for English Learners (ELs). https://www.gadoe.org/External-Affairs-and-Policy/State-Board-of-Education/SBOE%20Rules/160-4-5-.02.pdf#search=english%20for%20speakers%20of%20other%20languages

[21] See Millard, M. (2015). State funding mechanisms for English language learners. Education Commission of the States. http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/01/16/94/11694.pdf

[22] Ibid.

[23] Public Schools of North Carolina. (2014). 2013-2014 allotment policy manual. https://www.dpi.nc.gov/docs/fbs/allotments/general/2013-14policymanual.pdf; Millard, M. (2015). State funding mechanisms for English language learners. Education Commission of the States. http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/01/16/94/11694.pdf

[24] Georgia Department of Education. QBE allotment sheet FY 2020.

[25] Georgia Department of Education. ESOL-subject matter teacher head counts, system and state level October 2019, Certified Personnel Information Data Collection System (CPI 2020-1)

[26] Based on a GBPI analysis of Georgia Department of Education. (2019). Gifted teacher counts (head counts and full time equivalent positions), system and state level October 2018, Certified Personnel Information Data Collection System (CPI 2019-1) and Georgia Department of Education. QBE allotment sheet FY 2019.

[27] Based on a GBPI analysis of Georgia Department of Education. (2019). Gifted teacher counts (head counts and full time equivalent positions), system and state level October 2018, Certified Personnel Information Data Collection System (CPI 2019-1).

[28] Sugarman, J. (2016). Funding an equitable education for English learners in the United States. Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute, 1-50. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/US-Funding-FINAL.pdf#:~:text=Funding%20an%20Equitable%20Education%20for%20English%20Learners%20in,level%20of%20funding%20based%20on%20their%20student%20profile.

[29] Ibid.

[30] U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). 2019 reading assessment.

[31] U.S. Department of Education. (2020). Pending cases currently under investigation at elementary-secondary and post-secondary schools as of October 2, 2020 7:30am search. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/investigations/open-investigations/tvi.html?queries%5Bstate%5D=GA&queries%5Btod%5D=Title+VI+-+English+Language+Learners

[32] Georgia Department of Education. Quality Basic Education – Reports FY 2003-2021. https://financeweb.doe.k12.ga.us/QBEPublicWeb/ReportsMenu.aspx

[33] Georgia Department of Education. District expenditure reports, fiscal years 2000 through 2019, and State mid-term allotment sheets, fiscal years 2000 through 2019, Georgia Department of Education.

[34] See Barnett, W. S., Yarosz, D. J., Thomas, J., Jung, K., & Blanco, D. (2007). Two-way and monolingual English immersion in preschool education: An experimental comparison. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(3), 277-293.; Castro, D. C., Garcia, E. E., & Markos, A. M. (2013). Dual language learners: Research informing policy. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute.; Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (2017). Validating the power of bilingual schooling: Thirty-two years of large-scale, longitudinal research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 203-217.; Peterson, E., & Coltrane, B. (2003). Culture in second language teaching. In Culture in Second Language Teaching. Center for Applied Linguistics.; MacSwan, J., & Rolstad, K. (2005). Modularity and the facilitation effect: Psychological mechanisms of transfer in bilingual students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 27(2), 224-243.; Restrepo, M. A., Morgan, G. P., & Thompson, M. S. (2013). The efficacy of a vocabulary intervention for dual-language learners with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research..

[35] See: Mahoney, K., Thompson, M., & MacSwan, J. (2005). The condition of English language learners in Arizona: 2005. The condition of pre-K–12 education in Arizona: 2005, 3-1.; Rolstad, K., Mahoney, K., & Glass, G. V. (2005). The big picture: A meta-analysis of program effectiveness research on English language learners. Educational policy, 19(4), 572-594..

[36] See Georgia Department of Education. Dual language immersion, ESOL, & federal programs. https://www.gadoe.org/Curriculum-Instruction-and-Assessment/Curriculum-and-Instruction/2019%20%202020%20HLS/Dual%20Language%20Immersion_ESOL_and_Federal%20Programs.pdf

[37] U.S. Department of Justice. (2020). Types of educational opportunities discrimination. https://www.justice.gov/crt/types-educational-opportunities-discrimination

[38] Georgia Department of Education. (2019). English learner (EL) students in gifted courses, by EL status/monitoring Level, system and state level school year 2018-19 student class data collection system, end of year signoff cycle (SC 2019-L)