As Georgians put the finishing touches on their returns to meet today’s income tax filing deadline, one benefit many are missing out on is a tax credit that states can offer to help average families get a fair deal. Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia provide taxpayers with a state-level match for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a federal program that gives a targeted tax cut to low- and middle-income workers with kids. It’s a well-documented fact that state EITCs are a good way to keep working families on the path to success by helping parents afford core needs like food and shelter as well as strategic investments like a reliable car to get to work. But a lesser-known benefit of the policy is the balance it brings to state and local tax systems as a whole, which tend to offer a better deal for those at the very top.

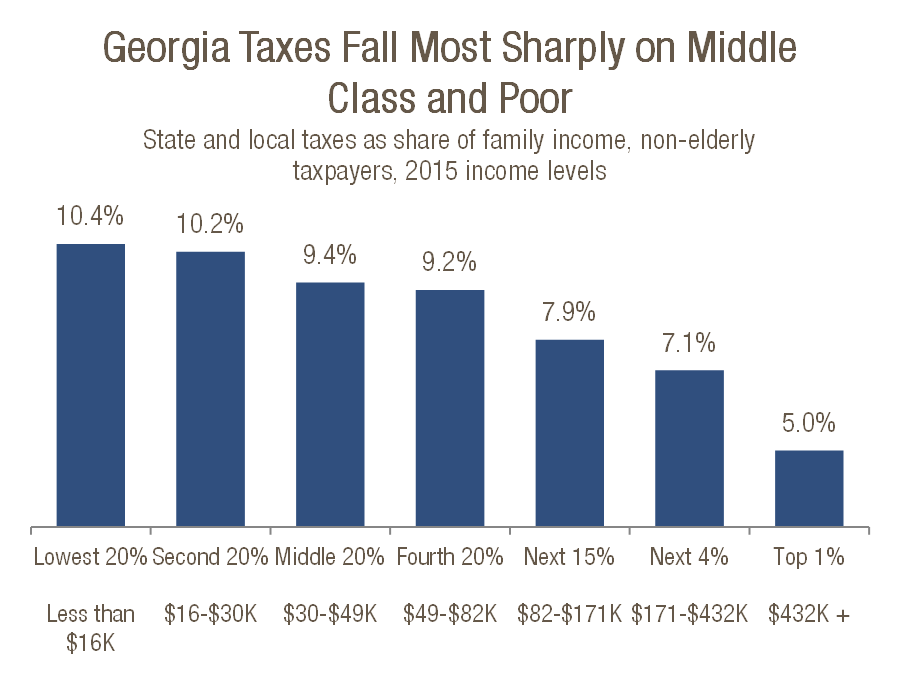

Many people assume state taxes fall most sharply on taxpayers with higher-incomes, since well-off households usually get larger income tax bills. But that ignores the range of ways people of all income levels contribute, including sales taxes on everyday purchases, property taxes on homes and apartments and excise taxes on goods such as motor fuel. Several of these revenue sources are “regressive,” because taxpayers of lesser means feel more of a pinch from the tax in question. Five dollars in sales taxes or fees means a lot more to a single mom struggling to afford child care than it does to a typical CEO.

When Georgia’s full range of levies and fees are tallied, taxpayers with low or modest incomes wind up paying a higher share of what they make. Georgia calls on the poorest fifth of families to pay 10.4 cents out of every dollar in state and local taxes. For the middle fifth of Georgians making $30,000 to $49,000 a year, it’s 9.4 cents of every dollar. That compares to only 5 cents on the dollar for the small sliver of households at the top, the wealthiest 1 percent of Georgians making at least $432,000 a year.

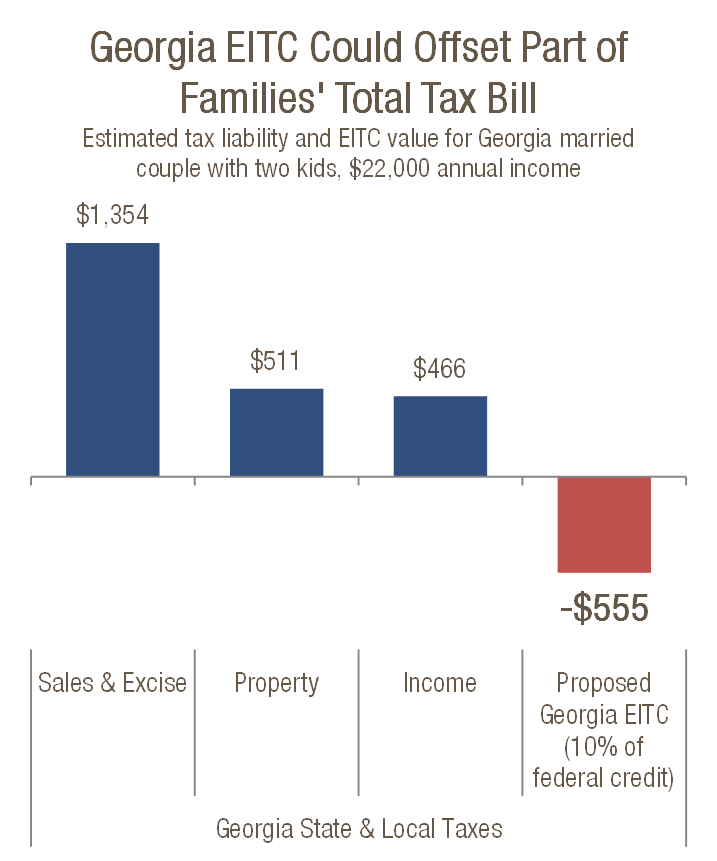

Creating a state EITC, or Georgia Work Credit, would deploy a time-tested tool to address that disparity by cutting taxes from the bottom up, rather than the top down. More than 1 million Georgia families, about 28 percent of all taxpayers, now claim the federal version of the credit and would be eligible for the state version too. Families that make from about $10,000 to $24,000 a year could get the largest boost, though households that make up to about $39,000 to $53,000 still benefit, depending on the number of dependent children. The value of the state version is set at a percentage of the federal credit, ranging from a low of 3.5 percent in Louisiana to 40 percent in Washington, D.C. GBPI previously proposed a 10 percent state match, which works out to a few hundred dollars for many families.

The accompanying chart shows one example of how a Georgia EITC might work. Take a hypothetical Georgia family of four, married with two kids and getting by through part-time work and odd jobs. At $22,000 in annual income, they pay Georgia’s state and local governments about $2,300 in combined income, property and sales tax. A Georgia EITC set at 10 percent of the federal credit would cut this family’s yearly tax bill by $555.

Not only does that cancel out the family’s state income tax bill, it also generates a small refund. That is because the tax credits are usually designed to be refundable, so qualified families can claim the full value of the credit even if it results in a refund. That core design feature allows the EITC to help those taxpayers who contribute a range of sales, excise and property taxes throughout the year but have relatively smaller income tax bills.

Georgia’s legislative session for 2016 is over, and lawmakers are starting to hit the campaign trail for the November election. If incumbents and challengers are looking for smart, affordable ways to help their constituents and provide a critical boost for families, they can take a close look at creating a Georgia Work Credit. Hardworking Georgians stand to get a fairer deal ahead of future income tax deadlines if lawmakers embrace the policy when the 2017 Legislature convenes in January.