Executive Summary

This report explores the complexity of student loan debt in Georgia. It details the magnitude of the student loan debt crisis and explains how the costs of college affect students. To understand how the student loan debt crisis affects Georgians specifically, this report analyzes quantitative data from the University System of Georgia (USG) and qualitative data collected from student loan borrowers who graduated from public colleges in Georgia. The author also explores how lawmakers can reduce student loan debt through a comprehensive need-based aid program and by fully investing in and revising the public higher education funding formula.

Investment in Public Higher Education is Good for All Georgians

Public higher education has been a cornerstone of Georgia’s development for centuries.[1] Therefore, it is imperative that state lawmakers fund postsecondary education equitably. Completing college has become more important as 66% of jobs in Georgia will require some postsecondary training by 2031.[2] However, many Georgians struggle to afford postsecondary education, and as a result, rely heavily on student loans to access higher education.

Historically, public institutions have granted students access to quality education. However, many states like Georgia have not fully invested in public higher education. Since 2001, USG has not met its 75% funding share as provided by funding formula, which means more cost has shifted to students.[3]

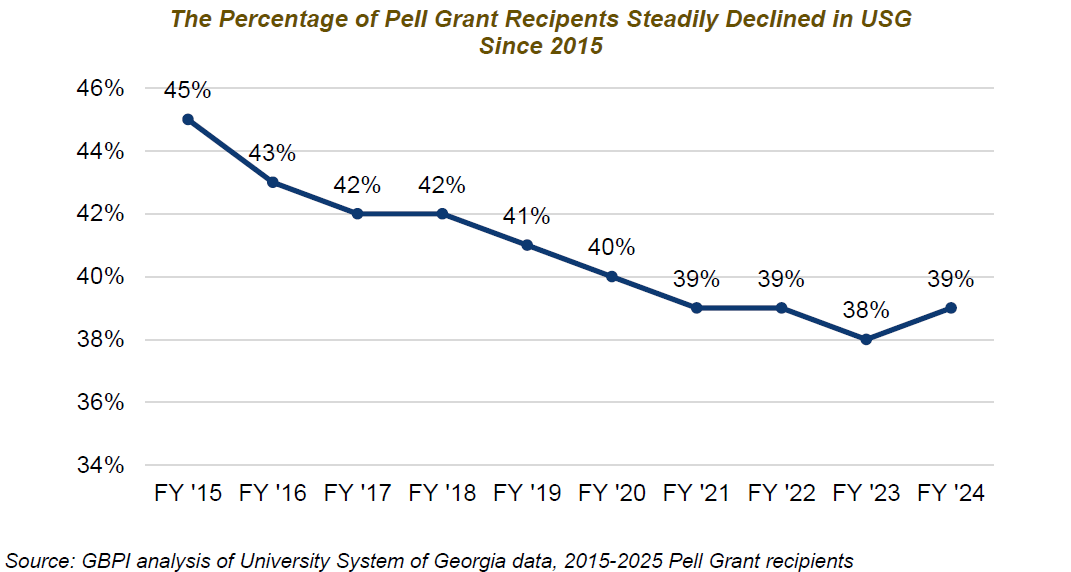

Many students have struggled to access postsecondary education. The cost of college has exponentially increased since the 1980s, outpacing the value of financial aid.[4] In Georgia, Pell Grant recipients in USG enroll at lower numbers than students who do not receive the Pell Grant, and Black and Hispanic students are more likely to be Pell-eligible and carry disproportionately more student loan debt.[5] The steady decline in Pell Grant recipients who enroll in USG indicates that some financially marginalized students, many of whom are students of color, are not enrolling in public four-year colleges in Georgia altogether.[6]

Between the state shifting more of the financial burden of college to students and the overall increasing cost of college, Georgians have navigated the difficult task of paying increased postsecondary expenses. In many cases, students are forced to decide whether to either forgo college or take out student loans to cover the cost. As these pressures mount on students, equitable investment in public higher education has lagged behind need, leaving financially marginalized students with fewer options to advance their education.

Now more than ever, Georgia lawmakers should prioritize public postsecondary education. Georgians deserve both full fiscal investment in higher education and state-sponsored financial aid to mitigate the student loan debt crisis.

The Student Loan Debt Crisis in the United States and Georgia

Student loan debt has increasingly burdened people in the U.S. in recent decades.[7] Many factors have contributed to this issue, such as inequitable distribution of wealth, systemic racism, rising college costs and government disinvestment.[8] The term, “student loan debt crisis” was introduced in 1988, and student loan debt has grown due to the dependence on the federal student loan program as the primary financial aid program used to subsidize higher education in the U.S. For example, from 2000 to 2020 the number of borrowers who owed public federal loans doubled from 21 million to 45 million, making student loan debt the fastest growing household debt.[9] When adjusted for inflation, federal student loan spending has almost tripled, increasing by 291% since 1980.[10] In addition, the total amount that U.S. borrowers owed quadrupled from $387 billion to $1.8 trillion.[11] If everyone in the U.S. held an equal amount of the student loan debt, per capita student loan debt would have been $1,375 in 2000 and $5,294 in 2024.[12] (You can view a full timeline of policy leading to and reacting to the student loan debt crisis in the appendix. The timeline is helpful for understanding what policies were in place when past and present generations of Georgians took out student loans.)

The state of Georgia:

- In 2025 has 1.7 million residents who owe student loans, totaling $71.7 billion in debt.[13]

- Is ranked third in the nation for highest average student loan debt, with Washington D.C. ranked first and Maryland ranked second.

- Has an average student loan debt of $42,226 and is one of only four states with average student loan debt exceeding $40,000.

In fiscal year 2024, the University System of Georgia’s (USG) total student loan debt was $789 million for current undergraduate students.[14]

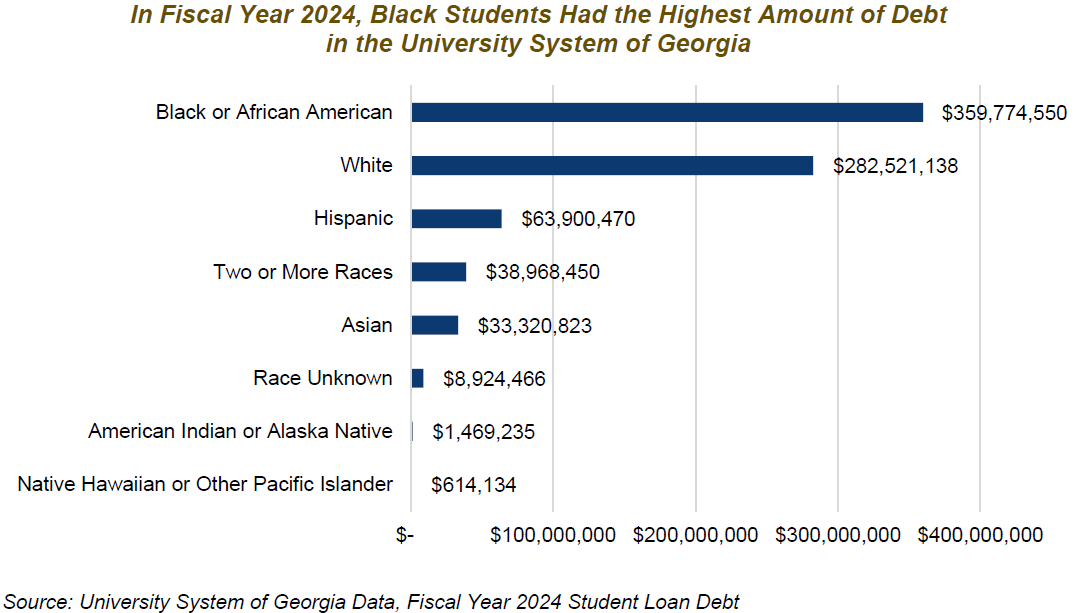

The student loan debt crisis is a racial equity issue. In 2024, Black students only represented 25% of students in USG;[15] however, they accounted for around 44% of Pell Grant recipients. Black students in USG carry 46% of the total student loan debt.[16]

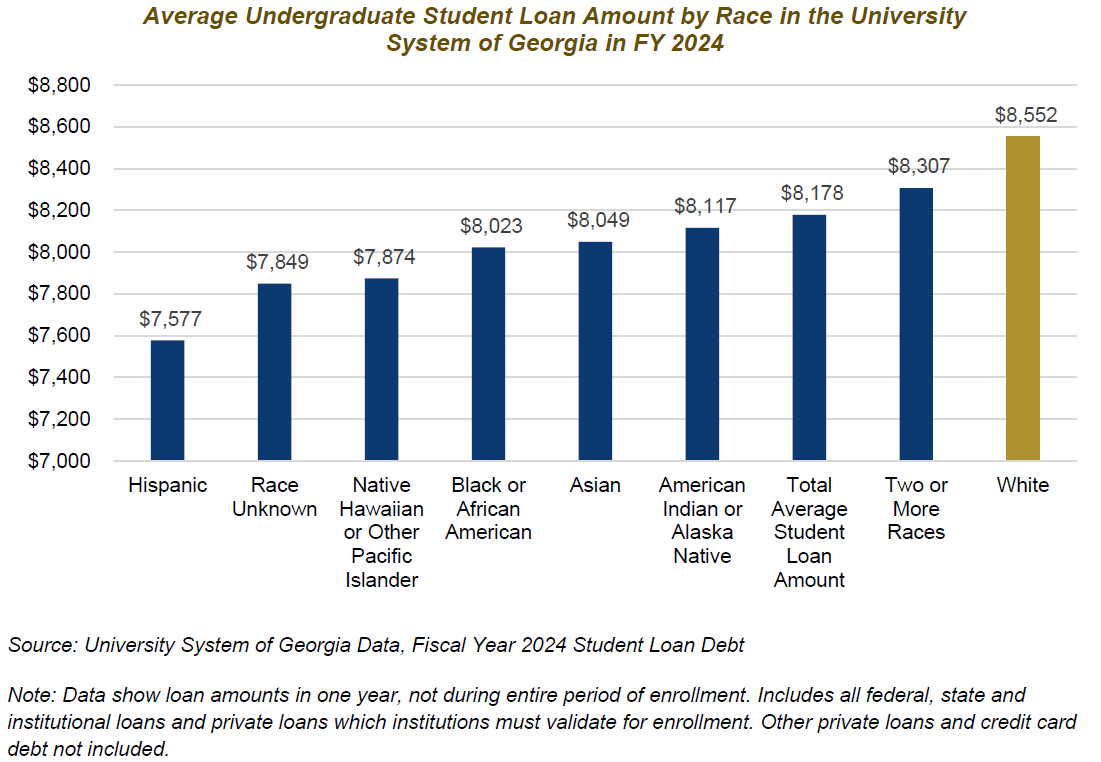

Despite Black students experiencing a disproportionate impact of student loan debt, white students also face college affordability challenges. In FY ‘24 white students had the highest average student loan debt of any racial group in USG.[17]

Access to student loans is critical for most students, especially students who are racially and financially marginalized. Without student loans, many of these Georgians would not be able to attend college. However, many student borrowers have questioned if their decision to take out student loans was worth the investment due to ballooning interest rates and long, punitive repayment processes.[18]

Many Georgians will continue to navigate barriers like student loan debt to be competitive in the workforce. Between 2021 and 2031, Georgia new jobs that require postsecondary training and education will increase by 420,000 while new jobs that require a high school diploma or less will only grow by 212,000.[19]

Intergenerational Student Loan Debt Stories

Student loan reduction is critical to postsecondary access and economic mobility.[20] For generations, Georgians have experienced financial challenges related to student loan debt burdens. Below are three examples of borrowers of different ages (Generation X, Millennial and Gen Z) who highlight their experience with student loan debt.

![]()

Student Loan Debt Perspective: Timothy

Demographics: White man, 47 years old (Generation X)[21], teen parent

Studied at: 4-Year Public Research University

Paid for College by: Working, HOPE Scholarship, Pell Grant and $45,000 in student loans

Response to borrowing money for college:

“I was going to college. And, you know, trying to juggle working and paying for the family home, at the age of 18 and 19, 20, while I was in school. So while a lot of college was paid for, I’d say probably 80% of my tuition and book fees were paid. I still had a relatively large bill there, but then also had to maintain a home for myself and the child and, and that wouldn’t have been possible [without student loans]. If I was just working and going to school, I don’t think that I could juggle that and still been able to afford that.”

Response to repayment and the interest rate:

“You know, getting it paid down was pretty difficult. I deferred the loans a bunch of times when I was young. So by the time I started paying them, actually making somewhat reasonable payments on them, the principal has skyrocketed. I was paying back $70,000 on a $45,000 loan.”

Response to receiving student loan debt cancellation:

Student Loan Debt Perspective: Keisha

Demographics: Black woman, 38 (Millennial)[22], first-generation college student, raised in single-parent household

Studied at: 4-Year Public University

Paid for College by: Working multiple jobs, grants, borrowed $80,000, the maximum amount from the U.S. Department of Education

Response to family’s ability to pay:

“They were not able to pay. At all. My mom did assist with Grant. I want to say maybe the first four months of school. But then after that it was no support whatsoever.”

Response on working multiple jobs through college:

“I’ve always been an independent and determined person. I’m sure it would have been a lot easier not working. But I knew if I didn’t work, I wasn’t going to eat. I had to work. So it was just life. Like it was just me surviving.”

Response on receiving some student loan debt cancellation as a public-service employee:

“Honestly, I feel like it’s just been a stress reliever. Even thinking about it, because I know my current wages would not allow me to also add in, a monthly payment to those loans. So it’s helped mentally.”

![]()

Student Loan Debt Perspective: Parker

Demographics: Black woman, 24 (Generation Z)[23]

Studied at: 4-Year Public Research University

Paid for College by: Parent support with food and clothing (not tuition), Pell Grant, HOPE Scholarship, borrowed $35,000 in student loans from the U.S. Department of Education plus $20,000 in private school loans

Response to family’s ability to pay:

“There was not much room in the budget for helping with college. Beyond, like, just supporting me as I was in it with, like, you know, food and basic necessities. There wasn’t much support available for paying for tuition.

Response to choosing a less affordable college:

In her interview, Parker discussed the nuance of why she chose not to undermatch—when students enroll at a less selective college than their academic qualifications permit. Undermatching is more common for racially marginalized students and generally is associated with lower graduation rates than those who enroll in colleges that best match their abilities.[24]

![]()

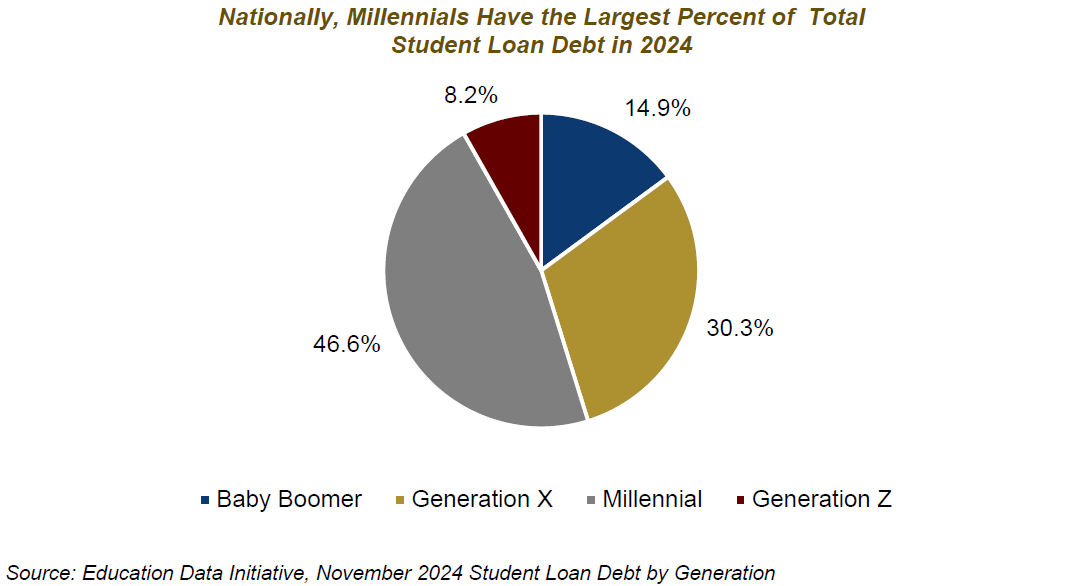

Nationwide, multiple generations are still struggling to pay off their student loans. Millennials have the largest percentage of student loans, as they had 47% of student loan debt in 2022.[25] Student borrowers from Generation X have the highest average student loan debt balance, $44,240 in 2024.[26]

While full data by generation is not available for Georgia, 47% of Georgia student loan borrowers are under the age of 35.[27] The amount of debt each Georgian has varies; 3% owe more than $200,000; and 14% of borrowers owe less than $5,000.[28]

Due to the burden of student loan debt, many people, millennials in particular, have delayed major economic milestones such as buying a home or starting a business.[29] Stories like Timothy’s, Keisha’s and Parker’s illustrate the personal challenges that represent many Georgians and their journey to afford college. Without lower college costs and more state investment to support financially marginalized students, many students in Georgia will continue to experience the student loan debt crisis firsthand.

Students with Low Incomes who Qualify for the Pell Grant are more likely to Forgo Higher Education or Take on More Debt

Over the past several decades postsecondary enrollment has increased nationwide; however, students who are financially marginalized have continued to lag middle- and upper-income students in enrollment.[30] Research shows that even when academic achievement is controlled for, financially marginalized students are less likely to enroll in postsecondary institutions than their affluent peers.[31]

The U.S. Department of Education defines the Pell Grant as the largest federal grant program offered to undergraduates. It is designed to assist students from low-income households. The maximum Federal Pell Grant award is $7,395 for 2025-2026.[32] For a Georgia student being raised by a single parent with a family size of two people, the parent could not make more than about $47,500 (225% of the poverty guideline, $21,150) per year in 2025 for the student to qualify for the maximum Federal Pell Grant Award.[33]

In Georgia, Pell Grant recipients in USG enroll at lower numbers than students who do not receive the Pell Grant. USG reported a 5.9% increase in overall enrollment for Fall 2023 for the second consecutive year, setting a record of 364,725 enrollees. Undergraduate enrollment grew by 10,329 between fall 2024 and fall 2025.[34] In 2014, 119,970 Pell Grant recipients were enrolled in USG, and in the academic year 2019-2020, the number of Pell Grant recipients in USG dropped by over 13,000 to 106,526. By 2024 102,000 Pell Grant recipients were attending public four-year postsecondary institutions in Georgia.[35]

Georgia Pell Grant recipients are enrolling at a lower rate than students who do not receive Pell Grants. Georgia Pell Grant recipients may also be more likely to take on more student loan debt than Georgians who do not receive Pell grants, which is a pattern seen at the national level.[36]

In 2017 and 2018, Pell Grant graduates with a bachelor’s degree accrued $26,863 on average in loans, and non-Pell Grant graduates borrowed 15% less, averaging $23,395. For two-year college graduates, Pell Grant recipients had an even higher average student loan debt of $16,370, around 34% higher than non-Pell Grant graduates who averaged $12,250 in student loan debt.[37] Despite a 5% decrease in Pell Grant recipients who enroll at USG, Georgia is seventh in the nation for the total amount of Pell Grant recipients with 228,026 recipients in 2024.[38]

USG Does Not Fund Schools Equitably, Nor Does It Pay its Historical Share of Funding[39]

There are two primary ways that states invest in public higher education: general operating support through direct funds to institutions and direct funding to students through financial aid programs.[40]

In Georgia, general operating funds are managed by the Board of Regents. Every year, the Board of Regents approves an annual budget request for USG, and funding is provided to each institution through the funding formula. Developed in 1982, USG’s enrollment-based formula is used to compute the amount of funding to cover the cost of educating students. There are four common factors that are generally included in a public higher education funding formula:[41]

- Enrollment– based on changes in full-time equivalent (FTE) student enrollment and enrolled credit hours.

- Base Funding– related to prior allocation amount to cover institutional operational needs such as new facilities and employee pay/benefits.

- Performance– state priority-driven financial incentives related to outcomes, retention, graduation and job placement rates.

- Equity– provides colleges with additional funding who enroll a higher number of students with low-income (i.e., Pell grant recipients).[42]

The USG formula includes only two factors, enrollment and base funding. Connected to these two factors are three USG formula components, one related to enrollment and two related to base funding:[43]

Enrollment

Full-time equivalent [FTE] students/number of enrolled credit hours (Enrollment Growth [2-year lag])[44]

+

Base Funding

Maintenance and Operations/Campus Square Footage (Building maintenance operations including utilities and custodial services)

USG Employee Fringe Benefits (Health insurance and employer retirement contributions

States and higher education systems have explored and implemented different approaches to building an equity factor into their formulas, with some focused specifically on the population served by a single institution, or cluster of institutions, like Historically Black Colleges and Universities.[45] Also, nearly three quarters of four-year performance-based funding systems incorporated a measure to enroll and graduate students who are racially marginalized.[46]

Due to its rigidity, traditional enrollment-based funding formulas like Georgia’s do not fully address the nuanced needs of 21st century college campuses, especially those that serve a high population of students of color.[47] The current USG funding formula could be aligned to what other states have done and could also better account for contemporary services that are critical to all students. Those services include supplemental supports for racially marginalized and first-generation college students, technological advances and mental health resources.[48] Also, the University System of Georgia’s funding formula can be used as a mechanism to combat student loan debt by more equitably focusing resources on Black students and others who may have to take on more debt to graduate.

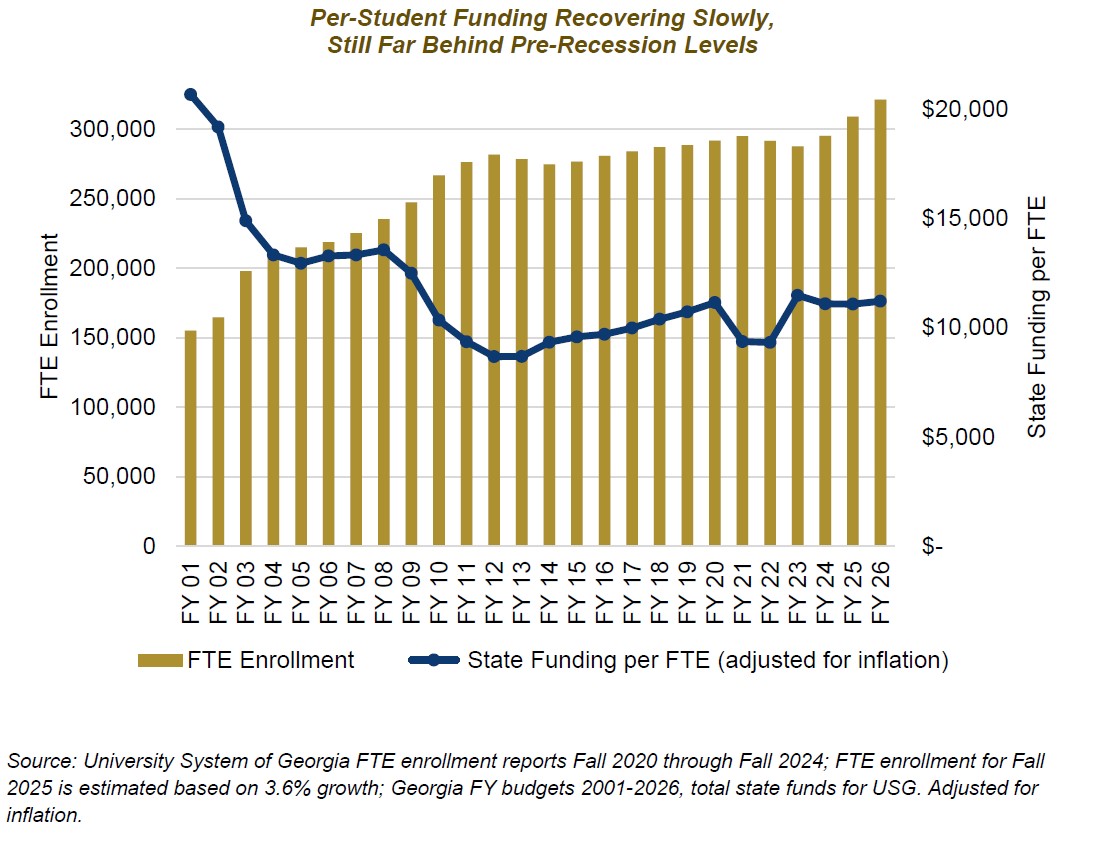

The University System of Georgia’s funding formula can be used as a mechanism to combat student loan debt.[49] However, USG state funds have not kept pace with inflation; funding per FTE decreased significantly over the last quarter century.

Since 2002, USG has not invested its share (75% of the state USG budget under the public higher education funding formula). In FY 2025, USG provided only 56%.[50] This 19% decrease in state funding results in more out-of-pocket costs for students and ultimately increases student loan debt amounts for students attending USG colleges and universities.

State policymakers can explore redesigning the USG enrollment-based funding formula, developed over 40 years ago, to meet modern-day demands. State policymakers can also commit to fully funding the USG 75% share of student funding. Both will be instrumental in ensuring that all Georgia students are successful in postsecondary education.

Georgia Does Not Offer Need-Based Financial Aid, But Could Afford It

In 2023, on average, states devoted 74% of funding to need-based aid, while Georgia only spent 1%.[51] In contrast, 99% of Georgia’s financial aid expenditures were spent on merit-based financial aid in the form of HOPE Scholarships at public two-year and four-year colleges and private institutions.[52]

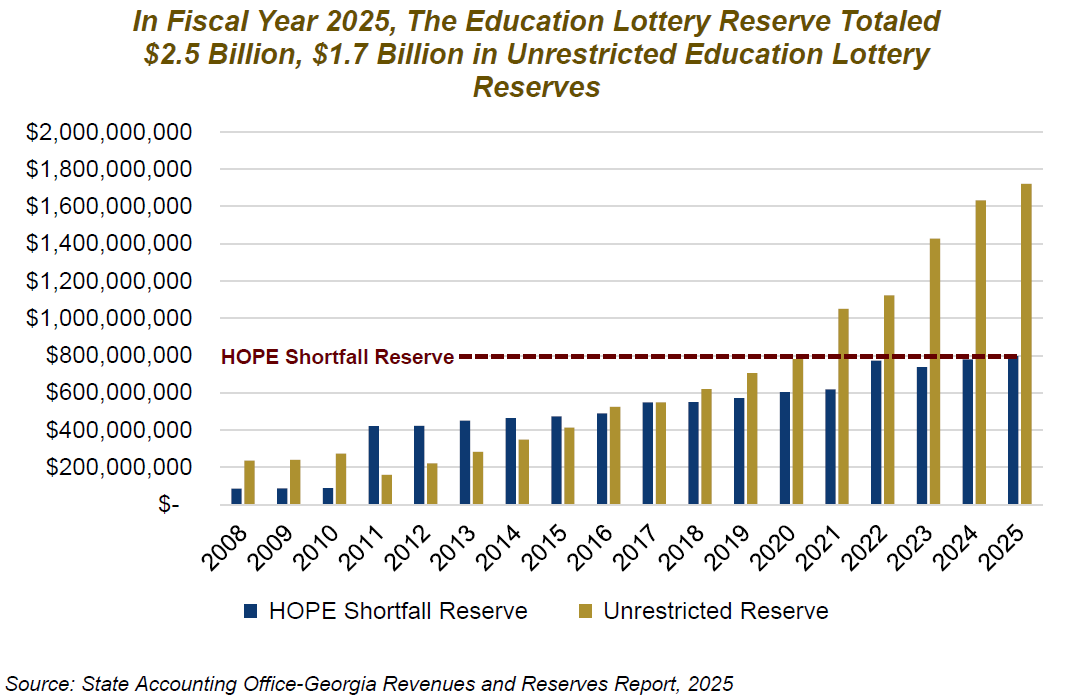

Georgia currently has the funding in the education lottery to invest in need-based financial aid. The education lottery account is required to maintain a minimum balance, called the shortfall reserve, of 50% of the previous year’s net lottery proceeds. If lottery ticket sales underperform, the state can draw on this reserve to fund the state’s merit-based HOPE scholarship. However, in the last 17 years, the education lottery account has amassed a consistent surplus known as the unrestricted reserve.

Over the last decade, education lottery funds have exceeded the amount required for the HOPE Shortfall Reserve. This has yielded $1.7 billion in the unrestricted reserve. Given this amount, state lawmakers can allocate funding to establish a need-based financial aid program.

Need-based financial aid is especially critical for Pell Grant recipients and other financially marginalized students who have unmet financial need. A significant measure of college affordability is “unmet need,” and refers to the gap between students’ total college costs and the funds available in financial aid and families’ resources.[53] Many Pell Grant recipients who have unmet need have historically been more likely to take out more student loans, face housing insecurity, work more hours and leave school without a credential.[54]

The rise in enrollment at USG and the consistent decrease in Pell Grant recipients’ enrollment is a critical disparity, and comprehensive need-based financial aid could help.[55] For example, a study on Florida’s Student Access Grant found that an additional $1,300 a year in need-based financial aid increased immediate enrollment at a public four-year college by 3.2% and had a 4.3 percentage points positive impact on first-year student persistence through the spring semester.[56] In this study, students with the most financial need were likely to immediately enroll, persist, and complete college sooner.[57] Alternatively, students who do not receive need-based aid in their second year of college and with the highest unmet need were more likely to drop out of college.[58]

State lawmakers could appropriate funding in the education lottery reserves to fund a need-based financial aid program.

Policy Recommendations

Fully Invest in the University System of Georgia

Approaches to address college affordability, reduce student loan debt and serve students equitably should all begin with the state paying its 75% share of the USG funding formula, increasing it from the 56% that it paid in FY 2025.

Revise the USG Funding Formula

The University System of Georgia should revise the funding formula and incorporate a financial incentive for equity. USG includes two factors in its funding formula base funding and enrollment funding:

Using equity as a factor in the state’s funding formulas would mean allocating additional funds to support institutions that enroll proportionately more students who are financially marginalized.

Establish a Comprehensive Need-based Aid Program

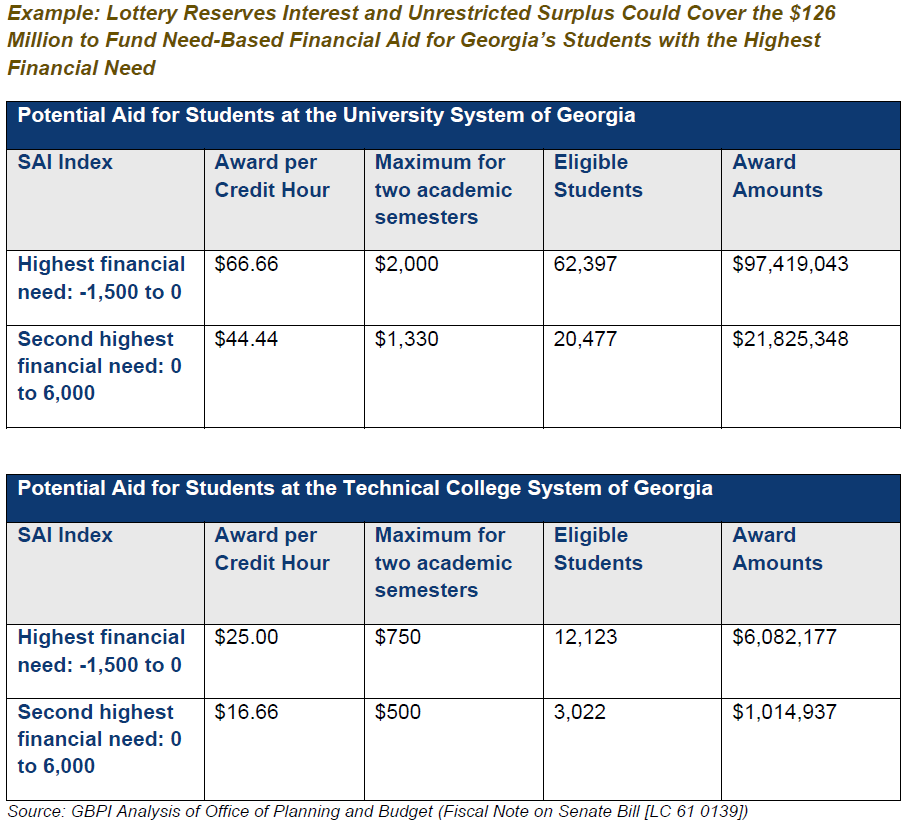

Using unrestricted lottery reserves funds and interest earned on the total education lottery could fund a generous comprehensive need-based financial aid program.

In the last four years the education lottery interest has grown exponentially. In 2024, in the example below, with approximately $124 million, roughly 98,019 students with the highest financial need could receive need-based financial aid to cover the cost of college.

A comprehensive program would include substantial and renewable funding for students beginning as first year students in USG and the Technical College System of Georgia (TCSG). To be eligible for this award, Georgia students would have to graduate high school with at least a 2.0 GPA and maintain satisfactory academic progress throughout college. An equitable need-based financial aid program would be based on the Student Aid Index (SAI), a formula-based index to determine Pell Grant eligibility.

In this example, the need-based award amount would include funding based on two SAI groups. Eligible students would receive financial aid per credit hour for up to 30 credit hours in an academic year for two semesters, fall and spring. Students with the highest financial need (SAI -1,500 to 0) would receive the highest amount of need-based financial aid per credit hour. With this investment in comprehensive need-based financial aid lawmakers can advance college affordability and reduce student debt in Georgia.

Conclusion

Student loan debt and the rising burden that it has placed on borrowers has been an escalating crisis in the U.S. and Georgia since the 1980s. Due to the rising cost of college and less public funding for postsecondary education, financial aid, namely need-based aid, has been outpaced by college expenses.

Racial equity is at the center of the student loan debt crisis. Pell Grant recipients are enrolling at a lower rate in USG than 10 years ago. Black students are more likely to be Pell-eligible and carry disproportionately more student loan debt. Mitigating student loan debt will also benefit the state’s economy, by providing access to postsecondary education to meet workforce demands. Subsequently, Georgians would potentially have more financial means to afford to purchase a home or start a family.

If elected officials and education leaders invest and revise the USG funding formula and state lawmakers establish a comprehensive need-based financial aid program, Georgia will reduce student loan debt. Advancing these solutions will address disproportionate student loan debt outcomes and help ensure that all Georgians have access to equitable post-secondary opportunities.

Appendix: History of the Student Loan Debt Crisis[59]

1956

Massachusetts Higher Education Assistance Corporation (MHEAC): In Massachusetts, MHEAC started a state-based guaranteed loan program with philanthropic donations from local business. This program model established the federal student lending program.[60]

1958

National Defense Education Act (NDEA): The Perkins Loan, the first federal loan program, was launched and was available to students on an income-need basis directly from the federal government. This act also established the first loan forgiveness policy, including a 15% reduction in payments each year for teachers.[61]

1965

The Higher Education Act (HEA): Created the Guaranteed Student Loan (GSL) program, a public/private partnership loan program that provided loans borrowed by low- and middle-income students from private loan companies; the loans were guaranteed by the federal government if students defaulted.[62] (HEA subsequently went through several reauthorizations.)

Undergraduate and graduate student loan limits increased per year with an aggregate limit of $5,000 and $7,500 respectively.[63]

Student borrowers were required to repay within 10 years in payments of at least $360 per year, this policy was known as the Standard Repayment Plan.[64]

1972

“The HEA Reauthorization Act established Educational Opportunity Grants for students with the greatest financial need, later known as Stafford Loans. It also created the Student Loan Marketing Association, now known as Sallie Mae.” [65] [66]

1976

The HEA Reauthorization Act began giving states incentives to establish loan guaranty agencies (Georgia Higher Education Assistance Corporation, now known as the Georgia Student Finance Commission), which ensure federal student loans provided by lenders.[67]

1980

The HEA Reauthorization Act: The Pell Grant program was developed as a federal need-based aid program for undergraduate students.[68] The Parent PLUS program was created to allow parents of dependent students to take out student loans on behalf of their students’ undergraduate education.[69]

1992

“The HEA Reauthorization Act established a pilot program of direct lending to students with the goal of converting the federal government’s guaranteed loans to a direct lending program.”[70] This reauthorization created the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) Program, including Stafford and PLUS loans.[71]

2005

The passage of the Higher Education Reconciliation Act (HERA) permitted graduate and professional students to borrow loans through the Parent Plus Program.[72] [73]

2007

The College Cost Reduction and Access Act (CCRAA) established the Income-Based Repayment Plan. In addition, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) Program was created. PSLF required full-time employment for a qualified employer and at the completion of 120 qualifying monthly payments, borrowers could be eligible for loan forgiveness.[74]

2011

The Income-Driven Repayment Plan introduced the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) via executive order. This repayment plan allowed borrowers to pay monthly payments equal to 10% of discretionary income.[75]

2020

Due to economic hardship during the COVID-19 pandemic, federal student loan payments and interest accrual on student loans were paused until 2023.[76]

2022

The Biden Administration passed an executive decision to cancel up to $20,000 for student loan borrowers based on income and current balance. However, many borrowers would not receive student loan debt relief due to a Supreme Court ruling in 2023, Biden v. Nebraska, claiming that the administration overstepped its authority to cancel student loan debt.[77]

2024

The Savings on a Valuable Education (SAVE) Plan was introduced through executive order as the most comprehensive income driven repayment plan to provide historic student loan forgiveness by lowering repayment terms, adjusting interest rates and loan forgiveness for borrowers who took out less than $12,000.

In less than a year, in a federal lawsuit, Missouri v. Biden (7 states including Georgia), sued the Biden Administration, and on October 3, 2024, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri issued an injunction to halt the student loan relief regulations like the SAVE Plan.[78]

2025

On July 4th, H.R.1 passed. This new law included many changes to federal student loan debt policies:

- A discontinuation of Grad PLUS Loan Program

- Graduate student loan limits- $20,500 per year in unsubsidized Stafford loans and a $100,000 lifetime limit. Professional students in medical and law school are limited to $50,000 per year and a $200,000 lifetime limit.

- The Parent PLUS loan will limit borrowers to $65,000 per dependent student each year.

- Student loan borrowers will have two repayment options. 1) the standard repayment plan and the new income-driven plan 2) Repayment Assistance Plan, based on borrowers’ income and family size.[79]

Appendix: Methodology

Using an intergenerational approach contextualizes how Georgians of different ages experience student loan debt. Additionally, this research focused exclusively on student borrowers who attended and graduated from college in Georgia. Many factors impact student loan debt, as such, the research chose to conduct qualitative interviews to gain a broader and more nuanced understanding about participants borrowing student loans.

Timeline

July 2025: The researcher developed interview questions that focused on understanding how borrowers and families navigated college costs and their ability to afford college. Interview questions focused on gaining insight into the participant’s support with securing money to go to college, their financial aid awards, while exploring how and why participants borrowed student loans.

To recruit participants, the researcher relied on their network of people who attended and graduated college in Georgia via email and phone calls. The researcher was intentional about reaching out to diverse participants for students. Interviewees represent different racial and gender groups and geographical locations including Atlanta Metropolitan area and southwest Georgia.

August 2025: The researcher scheduled and conducted interviews with participants. Participation was voluntary, and interviewees confirmed their consent via email and verbally before the interview.

September 2025: Interview transcripts were generated, and thematic analysis was used. Patterns were identified in student and staff interviews to find themes within the data. Once the data was analyzed, the researcher wrote the report. In instances when interview audio clips were used, the researcher followed up with interviewees to confirm their consent to share the data in this format.

Endnotes

[1] University System of Georgia. Information Digest 2000-2001, Brief history. https://usg.edu/research/digest/2001/history/1.php

[2] Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. (n.d.). After everything: Projections of jobs, education, and training requirements through 2031 (p. 54). Retrieved August 17, 2025 from https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/projections2031/

[3] Young, A. (2025, June 30). Georgia state education primer for Fiscal Year 2026. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgia-education-primer-for-state-fiscal-year-2026/

[4] Taylor, B. J., & Cantwell, B. (2019). Unequal higher education: Wealth, status, and student opportunity. Rutgers University Press.

[5] NASFAA. (2022). Doubling the maximum Pell grant. In NASFAA Issue Brief: Vol. AUGUST 2022 [Issue brief]. Retrieved October 30, 2025 from https://www.nasfaa.org/uploads/documents/Issue_Brief_Double_Pell.pdf

[6] Author analysis of University System of Georgia Data, 2015-2025 Pell Grant recipients; University System of Georgia. Financial aid and HOPE scholarship reports, Pell grant recipients by amount, undergraduates. https://www.usg.edu/research/financial_aid_hope_scholarship_reports

[7] Hanson, M. (2025, July 9). Student loan debt crisis (explained): Facts, causes & effects. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-crisis#1

[8] Perry, A. M., Steinbaum, M., & Romer, C. (2021, June 23). Student loans, the racial wealth divide, and why we need full student debt cancellation. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/student-loans-the-racial-wealth-divide-and-why-we-need-full-student-debt-cancellation/

[9] Ibid.

[10] Hanson, M. (2024, July 14). Student loan debt crisis (explained): Facts, causes & effects. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-crisis#1

[11] Looney, A., & Yannelis, C. (2024, September 17). What went wrong with federal student loans? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-went-wrong-with-federal-student-loans/

[12] Meyer, J. (2001, October). Census 2000 brief: Age: 2000. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2001/dec/c2kbr01-12.html; US Census. (2021, April). Wilder, K. (2024, December 19). New 2024 population estimates show nation’s population grew by about 1% to 340.1 million since 2023. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2024/12/population-estimates.html

[13] Hanson, M. (2025, June 26). Student loan debt by state [2025]: Average + total debt. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-state#georgia

[14] Ibid.

[15] The University System of Georgia. (Fall 2024). Fall 2024 semester enrollment report for all students. https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/enrollment_reports/Fall_2024_SER.pdf

[16] The University System of Georgia. (2024). Student loan debt by race [Data set]

[17] Ibid.

[18] Mustaffa, J. B., & Davis, J. C. (2021). Jim Crow debt: How Black borrowers experience student loans. The Education Trust. https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Jim-Crow-Debt_How-Black-Borrowers-Experience-Student-Loans_October-2021.pdf

[19] Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. (n.d.). After everything: Projections of jobs, education, and training requirements through 2031 (p. 54). https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/projections2031/

[20] The impact of student debt on the low-wage workforce. (2023, September 26). WorkRise Network. https://www.workrisenetwork.org/working-knowledge/impact-student-debt-low-wage-workforce

[21] Born between 1965 and 1980.

[22] Born between 1981 and 1996.

[23] Born between 1997 and 2012.

[24] Jagesic, S., Ewing, M., Wyatt, J. N., & Fing, J. (2021, June 10). Understanding the relationship between dual enrollment participation, college undermatch, and bachelor’s degree attainment. Research in Higher Education, 63, 119-139. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11162-021-09643-x

[25] Hanson, M., & Hanson, M. (2024, November 21). Student loan debt by generation (2024): Millennials, Gen Z, etc. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-generation

[26] Ibid.

[27] Hanson, M., & Hanson, M. (2025, June 26). Student loan debt by state [2025]: average + total debt. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-state#georgia

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Castleman, B. L., & Long, B. T. (2016). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(4), 1023-1073.

[31] Ellwood, D. T., & Kane, T. J. (2000). Who is getting a college education? Family background and the growing gaps in enrollment. In S. Danzinger & J. Waldfogel (Eds.), Securing the future: Investing in children from birth to college. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

[32] U.S. Department of Education. Federal Student Aid, 2025-2026 federal student aid handbook. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2025 from https://studentaid.gov/understand-aid/types/grants/pell

[33] U.S. Department of Education. 2024-25 DRAFT SAI guide supplement: Eligibility for max/min Pell Grant resource. https://fsapartners.ed.gov/sites/default/files/2023-05/202425DRAFTSAIGuideSupplementEligibilityforMaxorMinPellGrantResource.pdf; poverty guideline for 2-person household in 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia is $21,150 for 2025, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.) 2025 poverty guidelines for the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia. https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines

[34] The University System of Georgia. (2025). Enrollment report: 2016-2023, bachelor’s degree level [Data set]

[35] University System of Georgia. (2014-2024). University System of Georgia Pell Grant Recipients [Data set]

[36] College Scorecard. (2024) College Scorecard Data by Field of Study [2024]. https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/assets/FieldOfStudyDataDocumentation.pdf; The Institute for College Access & Success. (2020, December 21). New data show recent graduates who received Pell grants left school with $6 billion more in debt than their peers. https://ticas.org/affordability-2/new-data-show-recent-graduates-who-received-pell-grants-left-school-with-6-billion-more-in-debt-than-their-peers/#:~:text=These%20data%20indicate%20that%20debt%20disparities%20for%20students,Graduate%20with%20Higher%20Median%20Debt%20than%20Higher-Income%20Peers

[37] Ibid.

[38] Hanson, Melanie. “Pell Grant Statistics” EducationData.org, 2024-11-03,

https://educationdata.org/pell-grant-statistics

[39] Cook, T. (2023, August 30). Formula funding overview to House Higher Education Ad Hoc Committee on Formula Funding and Program Access & Delivery. https://cdn.ymaws.com/georgiacolleges.org/resource/collection/994E67A0-6079-4663-9497-375C04F8BE3B/Tracey_Cook_HE_Committee_Formula_Overview.pdf, slide 7, State share of formula, “Cost sharing between the state and students, with state covering 75% and students 25% through tuition.” In FY 2024, state funding only accounted for 57%.

[40] SHEEO. (2025, February 5). Public investment in higher education: Research, strategies, and policy Implications – SHEEO. SHEEO – State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. https://sheeo.org/project/public-investment-in-higher-education-research-strategies-and-policy-implications/

[41] Baker, D. J., Ortagus, J., Rosinger, K., & Lingo, M. (2024, August 9). Designing state funding formulas for public higher education to center equity. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/designing-state-funding-formulas-for-public-higher-education-to-center-equity/

[42] Ibid.

[43] Cook, T. (2023, August 30). Formula funding overview to House Higher Education Ad Hoc Committee on Formula Funding and Program Access & Delivery. https://cdn.ymaws.com/georgiacolleges.org/resource/collection/994E67A0-6079-4663-9497-375C04F8BE3B/Tracey_Cook_HE_Committee_Formula_Overview.pdf, slide 6; see also, Cook, T. (2023, August 30). Recorded presentation to same funding committee. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/live/fHRanjwVef4 (29:24 in video); (T. Cook, personal communication, June 6, 2023).

[44] University System of Georgia. (2011, November). Funding formula overview. PowerPoint presentation, slide 11. https://www.usg.edu/fiscal_affairs/assets/fiscal_affairs/documents/Consolidated_Formula_Presentation_-_November_Board_-_Final.pdf

[45] Baker, D. J., Ortagus, J., Rosinger, K., & Lingo, M. (2024, August 9). Designing state funding formulas for public higher education to center equity. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/designing-state-funding-formulas-for-public-higher-education-to-center-equity/

[46] Ibid.

[47] Richmond, M. (2025, May 21). Higher education needs funding formulas. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/briefs/higher-education-needs-funding-formulas/

[48] University System of Georgia. (2023, January 18). Georgia General Assembly 2023 joint budget hearings. PowerPoint presentation, slide 5. https://www.legis.ga.gov/api/document/docs/default-source/house-budget-and-research-office-document-library/2023-joint-budget-hearings/university_system_of_georgia.pdf?sfvrsn=988b9e51_2

[49] Ibid.

[50] House Appropriations Subcommittee on Higher Education. (2025). University system overview.

[51] Ma, J., Pender, M., & Oster, M. (2024). Trends in college pricing and student aid 2024, at 49. College Board. https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/Trends-in-College-Pricing-and-Student-Aid-2024-ADA.pdf

[52] National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs. (2023). Grant Aid 1974 to 2023 [Data set]. https://www.nassgapsurvey.com/

[53] Bell, L. (2023, August 16). College affordability still out of reach for students with lowest incomes, students of color – IHEP. IHEP. https://www.ihep.org/college-affordability-still-out-of-reach-for-students-with-lowest-incomes-students-of-color/

[54] IHEP. (2021, August 5). The cost of opportunity: Student stories of college affordability – IHEP. https://live-ihep-wp.pantheonsite.io/publication/the-cost-of-opportunity-student-stories-of-college-affordability/

[55] Castleman, B. L., & Long, B. T. (2016). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Journal of Labor Economics, 34, 1023, 1026.

[56] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Overall timeline drawn from: A brief history of student loans | FAIR Student Loans. (n.d.). 2025 Boston University. Retrieved August 19, 2025 from https://www.bu.edu/fairstudentloans/a-brief-history-of-student-loans/

[60] Parker, T. D. (2006). What the world needs now: Cross-national student loan programs. Journal of the New England Board of Higher Education, 21(2), 19. http://www.nebhe.org/ info/journal/issues/Connection_Fall06.pdf

[61] National Defense Education Act of 1958. (P.L. 85-864). United States statutes at large, 72 Stat. 1587. Sec. 207. http://www.gpo. gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-72/pdf/STATUTE-72Pg1580.pdf

[62] Higher Education Act of 1965. (P.L. 89-329). United States statutes at large, 79 Stat. 1236. Title IV: Part B, Sec. 421. http://www.gpo.gov/ fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-79/pdf/STATUTE-79-Pg1219. pdf

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] A brief history of student loans | FAIR Student Loans. (n.d.). 2025 Boston University. Retrieved August 19, 2025 from https://www.bu.edu/fairstudentloans/a-brief-history-of-student-loans/

[66] Education Amendments of 1972. (P.L. 92-318). United States statutes at large, 86 Stat. 265. Sec. 133(a). http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg235.pdf

[67] Education Amendments of 1972. (P.L. 92-318). United States statutes at large, 86 Stat. 265. Sec. 133(a). http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg235.pdf

[68] A brief history of student loans | FAIR Student Loans. (n.d.). 2025 Boston University. Retrieved August 19, 2025 from https://www.bu.edu/fairstudentloans/a-brief-history-of-student-loans/

[69] Education Amendments of 1972. (P.L. 92-318). United States statutes at large, 86 Stat. 265. Sec. 133(a). http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg235.pdf

[70] A brief history of student loans | FAIR Student Loans. (n.d.). 2025 Boston University. Retrieved August 19, 2025 from https://www.bu.edu/fairstudentloans/a-brief-history-of-student-loans/

[71] Higher Education Amendments of 1992. (P.L. 102-305). United States statutes at large, 106 Stat. 569. Sec. 451. http://www.gpo. gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-106/pdf/STATUTE-106Pg448.pdf

[72] A brief history of student loans | FAIR Student Loans. (n.d.). Boston University. Retrieved August 19, 2025 from https://www.bu.edu/fairstudentloans/a-brief-history-of-student-loans/

[73] Higher Education Reconciliation Act of 2005. (P.L. 109-171). United States statutes at large, 120 Stat. 159. Sec. 8005(c)(1)(A). http:// www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-109publ171/pdf/ PLAW-109publ171.pdf

[74] College Cost Reduction and Access Act. (P.L. 110-84). United States statutes at large, 121 Stat. 792. Sec. 203. http://www. gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ84/pdf/PLAW110publ84.pdf

[75] White House, Office of the Press Secretary. (2011, October 25). FACT sheet: Help Americans manage student loan debt. Washington, DC: Author. https://www.whitehouse.gov/thepress-office/2011/10/25/fact-sheet-help-americansmanage-student-loan-debt

[76] A brief history of student loans | FAIR Student Loans. (n.d.-b). Boston University. https://www.bu.edu/fairstudentloans/a-brief-history-of-student-loans/

[77] Federal Student Aid. (n.d.). Retrieved September 28, 2025 from https://studentaid.gov/manage-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/debt-relief-info

[78] Attorney General Bailey announces challenge to Biden’s latest illegal student loan plan | Attorney General Office of Missouri. (n.d.). Retrieved September 28, 2025 from https://ago.mo.gov/attorney-general-bailey-announces-challenge-to-bidens-latest-illegal-student-loan-plan/

[79] ACE’s Division of Government Relations and National Engagement. (2025). One Big Beautiful Bill Act (H.R. 1).