Last week, Georgia leaders announced an unprecedented plan to seek federal waivers that could extend health care access to hundreds of thousands of people across the state. Senate Bill 106, the Patients First Act, aims to make Georgia the first-ever state to receive a 90 percent match in federal funding for a partial Medicaid expansion.[1] Although the legislation is quickly advancing in the Senate, the state has yet to release any estimates of how many Georgians could gain coverage or how much the plan will cost taxpayers. This analysis evaluates how the Medicaid waivers authorized by Senate Bill 106 could impact access to health care and the state budget.

The Patients First Act Proposes Unprecedented Medicaid Eligibility Limits

In fewer than 100 words, the Patients First Act authorizes changes to the law that could generate more than a billion dollars in new state and federal spending. However, both the cost and viability of the Medicaid waivers allowed under this plan will depend on whether Georgia’s leaders can win approval from federal regulators to implement the nation’s most limited expansion of Medicaid eligibility.

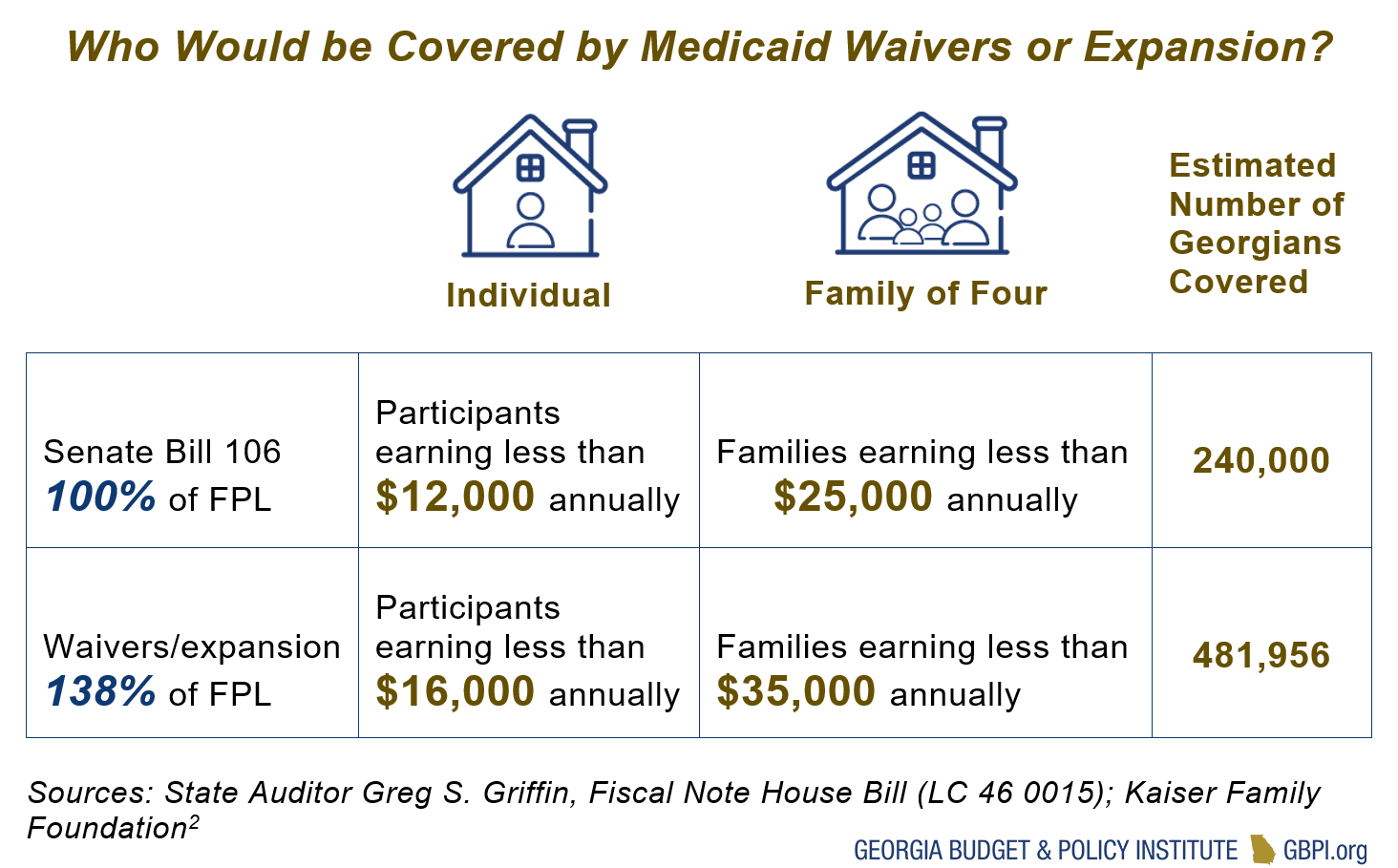

As proposed, Senate Bill 106 allows the Department of Community Health to request waivers to increase Medicaid coverage up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Under these guidelines, participants would have to earn less than $12,000 as an individual or about $25,000 for a family of four.

This approach would represent a major departure from the Medicaid eligibility guidelines adopted by 36 other states across the nation since 2010. The key feature of every 1115 Medicaid waiver approved under the Affordable Care Act—including the most conservative examples in Arkansas, Indiana and Kentucky—is each state’s decision to expand eligibility up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, which translates to about $16,000 a year for an individual or $35,000 for a family of four. In return, the federal government agrees to pay 90 percent of the costs associated with extending health care access to this newly eligible group, while permitting states to waive different rules and regulations to achieve targeted goals.

Arkansas, Massachusetts and Utah previously submitted waiver requests that mirror the eligibility guidelines authorized by Senate Bill 106 and none received approval for enhanced federal funding. All of these states declined to increase eligibility under their standard Medicaid funding rates because costs would be exponentially higher without a 90 percent federal match. In Georgia, enhanced funding means that the state would pay about one-third of what it currently costs to cover each Medicaid patient.[2]

Regulators tasked with reviewing waiver applications for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) have so far resisted these limited waiver requests. Experts suggest that these plans were not approved because it costs the federal government more to cover individuals between 100 and 138 percent of the FPL through the individual marketplace than with Medicaid.[3] CMS applies a “budget neutrality” standard to Medicaid proposals. Any state plan to waive federal laws cannot cause the federal government to spend more than it otherwise would under the Affordable Care Act. [4] In 2018, CMS issued a detailed statement on this issue explaining that the agency would not approve a waiver project unless it is “neutral to the federal government” and takes into account “hypothetical expenditures” or “expenditures for populations or services which could have otherwise been covered via the Medicaid state plan.”[5] Unless Georgia receives direct assurances that the federal government will reverse this long-standing position, the state should be prepared to submit an alternative plan that increases eligibility to draw down the full share of funding available.

If the federal government does, in fact, begin offering a 90 percent match for states that cap Medicaid eligibility at 100 percent of the poverty level, it would initiate a seismic policy shift. The regulatory changes required to authorize the type of partial Medicaid expansion prescribed by Senate Bill 106 would promise major implications for Georgia and most certainly result in major coverage changes for millions of people across the nation. To be sure, such a decision would mark the most significant change in federal health policy since 2012 when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Affordable Care Act’s initial mandate for all states to automatically expand Medicaid eligibility to 138 percent of the poverty level.

Calculating the Costs and Benefits of Increasing Medicaid Eligibility

To provide access to health care for two million patients, the state of Georgia spends more than $3.2 billion annually on Medicaid, matched by more than $7 billion in federal funding. Estimating the costs of any Medicaid waiver requires state leaders to first determine who will gain access to health care and how they will be covered.

To provide access to health care for two million patients, the state of Georgia spends more than $3.2 billion annually on Medicaid, matched by more than $7 billion in federal funding. Estimating the costs of any Medicaid waiver requires state leaders to first determine who will gain access to health care and how they will be covered.

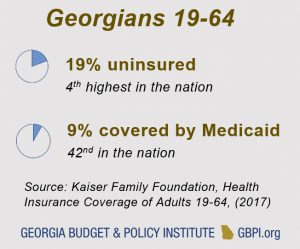

The most recent data available show that among Georgians between 19 to 64, 19 percent are uninsured, the 4thhighest rate in the nation. Only 9 percent of this population is currently covered by Medicaid, the nation’s 42nd lowest level.[6] Rural communities also face serious financial challenges compounded by disproportionally high levels of uninsured residents in the state’s poorest areas. Since 2010, seven rural hospitals have shut their doors, while many more are struggling to manage high levels of uncompensated care, a shortage of health care professionals and caring for both an aging population and patients with chronic health conditions.[7]

Georgians in the Coverage Gap

If there is consensus that one of Georgia’s central objectives is to provide Medicaid coverage to those who are currently uninsured and fall below 100 percent of the poverty level – as the Patients First Act would allow – then the state should be prepared to pay for a plan that grows its Medicaid program by at least 240,000 patients.[8]

This population represents a portion of those who fall into the state’s coverage gap, a group of uninsured Georgians with earnings below 100 percent of the poverty level who do not currently qualify for Medicaid, are unable to access coverage through their employer and earn too little to obtain any subsidies from the federal insurance exchange. If the state does not intend to cover this population with section 1115 waivers, these citizens are likely to remain uninsured. Without solutions that result in this group gaining access to medical coverage, it is unclear how Georgia will otherwise address the most persistent challenges facing the state’s health care system.

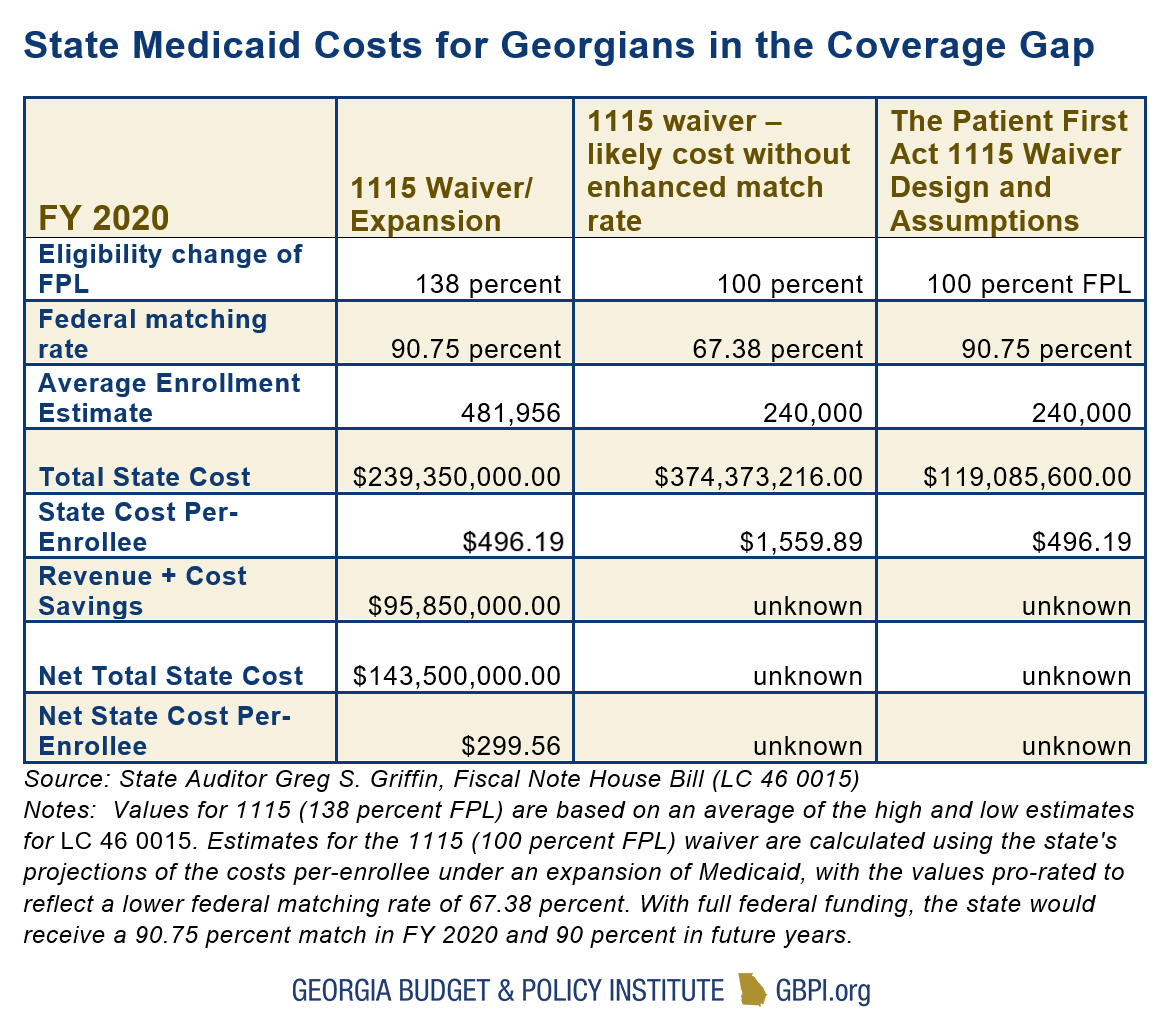

The chart below illustrates the costs to the state under both an 1115 waiver and Medicaid expansion scenarios. This assumes that any Medicaid waiver will attempt to increase access to health care for more than 240,000 Georgians who are currently without any other affordable coverage options.

In FY 2020, the federal government will finance 67.38 percent of the costs of Georgia’s Medicaid program under a formula called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) – a rate calculated by weighing each state’s average per capita income against the national average.[9] Annually, Georgia spends approximately $950 in state funds to cover each of the more than 1.35 million patients who are currently enrolled in the state’s Low-Income Medicaid program.[10]

State auditors estimate that if eligibility for Medicaid were increased up to 138 percent of poverty, between 437,000 and 527,000 Georgians would be added to the program in FY 2020. Averaging estimates for costs and enrollment, the state would also be on track to benefit from nearly $96 million in agency savings and additional revenues, resulting from an immediate infusion of more than $2 billion in total Medicaid funding. Overall, the annual net cost of either a waiver or expansion that covers Georgians up to 138 percent of the FPL is projected to amount to approximately $143.5 million or about $300 per enrollee.[11]

Without accounting for any potential increase in revenues or savings under either scenario, it would cost more than three times as much to cover each patient using the current FMAP rate of 67 percent rather than the enhanced 90 percent matching rate available under the Affordable Care Act.[12] Although there is considerable uncertainty that makes it difficult to accurately project the costs associated with attempting to increase Medicaid eligibility to 100 percent of the poverty level, it is clear that doing so under Georgia’s current FMAP rate would cost more than twice as much as traditional Medicaid expansion to cover half as many patients.[13] Also, as the state per capita income increases over time, any program that relies on the FMAP rate will be subject and sensitive to relative declines in federal funding. Over the long-term, applying this trend to a larger population of patients would create upward pressure on the state budget.

Without accounting for any potential increase in revenues or savings under either scenario, it would cost more than three times as much to cover each patient using the current FMAP rate of 67 percent rather than the enhanced 90 percent matching rate available under the Affordable Care Act.[12] Although there is considerable uncertainty that makes it difficult to accurately project the costs associated with attempting to increase Medicaid eligibility to 100 percent of the poverty level, it is clear that doing so under Georgia’s current FMAP rate would cost more than twice as much as traditional Medicaid expansion to cover half as many patients.[13] Also, as the state per capita income increases over time, any program that relies on the FMAP rate will be subject and sensitive to relative declines in federal funding. Over the long-term, applying this trend to a larger population of patients would create upward pressure on the state budget.

Even if Georgia is successful in becoming the nation’s first state to receive full federal funding for a Medicaid waiver that increases coverage up to 100 percent of the poverty level, the plan will still carry significant costs to the state. If the costs per enrollee mirror those under a full expansion of Medicaid, then the state would be required to pay approximately $119 million to extend coverage to about 240,000 Georgians. In any case, before legislators send legislation to the governor’s desk, it is vitally important for the General Assembly to conduct a full fiscal analysis that determines the net cost to the state of increasing Medicaid eligibility at both 100 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Based on this preliminary analysis of currently available data, it is not at all clear if proposals with the lowest eligibility thresholds would carry correspondingly low costs to the state.

Waivers are an opportunity to lay the groundwork for transformative health care reforms that could significantly increase access to care, improve health outcomes for Georgia patients and draw down billions in additional funding. To take full advantage of this opportunity, state leaders must make certain that the Department of Community Health has a viable path forward to negotiate the best deal possible for hardworking Georgia families.

Endnotes

[1] Andy Miller, “Senate panel backs waiver bill to insure more Georgians,” Georgia Health News, February 19, 2019.

[2] State Auditor Greg S. Griffin, “Fiscal Note House Bill (LC 46 0015,) Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts, January 18, 2019; “2018 Annual Report,” Georgia Department of Community Health, June 30, 2018

[3] James C. Capretta, “Allowing partial Medicaid expansion would increase federal costs,” RealClearPolicy (January 15, 2019)

[4] Timothy B. Hill, “Re: Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects,” Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (August 22, 2018)

[5] Timothy B. Hill, “Re: Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects,” Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (August 22, 2018)

[6] “Health Insurance Coverage of Adults 19-64,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, (2017)

[7] Ayla Ellison, “Georgia hospital to close July 26,” Becker’s Healthcare: Hospital Review, July 24, 2018

[8] Rachel Garfield, Anthony Damico, and Kendal Orgera, “ The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, June 12, 2018

[9] “Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Accessed February 18, 2019

[10] “2018 Annual Report,” Georgia Department of Community Health, June 30, 2018

[11] State Auditor Greg S. Griffin, “Fiscal Note House Bill (LC 46 0015,) Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts, January 18, 2019

[12] State Auditor Greg S. Griffin, “Fiscal Note House Bill (LC 46 0015,) Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts, January 18, 2019; “2018 Annual Report,” Georgia Department of Community Health, June 30, 2018

[13] State Auditor Greg S. Griffin, “Fiscal Note House Bill (LC 46 0015,) Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts, January 18, 2019; “2018 Annual Report,” Georgia Department of Community Health, June 30, 2018