|

Federal health care waivers allow states to “waive” or be exempt from certain federal health program requirements. States can try new approaches to managing health programs if they meet certain requirements for federal approval.

|

Many Georgians face challenges when trying to access quality health care and health-related services. About 1.4 million residents lack health insurance, often causing them to delay care. Hospitals are also negatively impacted by the high rate of uninsured people because they often do not get paid for the care they provide. Georgians also have poorer health outcomes compared to many other states.

Georgia ranks 46th in overall access to quality care and has high rates of chronic disease, maternal mortality and HIV/AIDs. Since 2010, seven rural hospitals have closed. Medicaid is Georgia’s largest health care program, providing health coverage to 2 million Georgians, but many Georgians are still not covered. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides a 90 percent federal match for states to expand Medicaid up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or $17,000 a year for an individual and $29,000 a year for a family of three. Expanding Medicaid to the almost 500,000 uninsured Georgians who would be eligible would help alleviate the problems listed above, but the state has thus far refused.

The Georgia legislature passed Senate Bill (SB) 106, the Patients First Act, which gives the state the authority to explore leveraging federal resources and implementing new solutions through two types of health care waivers. This report will focus on the Medicaid 1115 waiver. For information on the 1332 waiver, see our other report.

States have successfully used Medicaid waivers to increase the number of people with health coverage, expand benefits for important health needs such as family planning services and substance abuse treatment and work on improving people’s health by addressing their health-related social needs. However, some states have tried approaches that resulted in harmful effects such as large numbers of people losing their coverage due to restrictive requirements. Georgia can take the best step toward improving health by using the Section 1115 waiver to:

- Fully expand Medicaid coverage to as many Georgians as possible and take advantage of enhanced federal funding to get the best financial deal for the state;

- Provide an economic boost for enrollees, instead of penalizing them by making them pay more than Medicaid typically requires or adding stipulations to keep coverage such as reporting work hours or locking people out of coverage; and

- Connect people to social supports such as workforce development, housing-related services and transportation to help people remain healthy outside of the doctor’s office.

Background on the Patients First Act

The Georgia General Assembly passed Senate Bill 106, the “Patients First Act,” on March 25, 2019, and Gov. Brian Kemp signed the bill into law two days later. The first part of the bill allows the Department of Community Health to submit an 1115 waiver request on or before June 30, 2020. The legislation permits expanding Medicaid income eligibility up to a maximum of 100 percent of the federal poverty line, or about $12,000 per year for an individual. This partial expansion falls short of what federal law allows and would only allow the state to receive 67 percent of the cost from the federal government.

The 1115 waiver was initially meant to work with a 1332 waiver, which is outlined in the second part of the Patients First Act. That waiver would modify rules related to the federal health care marketplace created under the ACA. Due to circumstances outlined in this report, these two waivers will no longer be able to work together in the way intended. Both types of waivers will follow their own separate process for submission.

Process for Submitting the 1115 Waiver (based on most current information)

The state is spending $1.92 million for Deloitte Consulting LLP to develop the request for the 1115 waiver (and the 1332 waiver). The 1115 waiver will have two 30-day public comment periods, one at the state level and one at the federal level. The 1115 waiver is also required to have public hearings. The state is required to respond to general themes from these comments and has the option to change the waiver application based on these suggestions. The state is currently planning to submit by December 31, 2019 (date is subject to change).

Medicaid’s Section 1115 Waiver

Medicaid is the state’s health insurance program for certain groups of residents with lower incomes. Medicaid pays for a significant amount of Georgia’s health services including half of births and three-quarters of nursing home care. Two-thirds of Georgians with Medicaid coverage are children, and about one-quarter are elderly or people with disabilities. Adults without children are not eligible for Medicaid in Georgia. Parents are only eligible if they make less than $6,612 a year for a family of three.[1] Only seven states make it harder for parents to get Medicaid coverage.[2] The federal government currently pays 67 percent of the total program cost, and the state pays the remaining 33 percent.

Since 2011, Georgia currently has had one approved 1115 waiver. This program, Planning for Healthy Babies, increases income eligibility for women to receive family planning services, but it does not cover any other services. Since the passage of the ACA, states have often used the 1115 waiver to expand Medicaid coverage to more low-income adults. Georgia is one of 14 states not to expand its Medicaid program. States have taken two paths to doing a Medicaid expansion; applying for an 1115 waiver is one of those paths. (see “Medicaid Expansion and Waivers: Two Possible Paths to Extending Health Coverage” for a full comparison of these two options).

The Patients First Act, signed into law in March 2019, only allows what is known as a “partial expansion,” because it does not extend eligibility up to 138 percent of the poverty threshold as is permitted under the ACA. Gov. Kemp’s team stated they intend to pursue a partial expansion and request the 90 percent federal match rate. Massachusetts, Arkansas and Utah made the same request, and none of these states received approval. Georgia lawmakers remained hopeful that they would be approved due to conversations with the federal government. However, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released a statement on July 29, 2019, when it rejected Utah’s proposal, stating it will not approve partial expansions at the higher federal matching rate.[3] Without this approval, the state can only expect the federal government to pay the current 67 percent of costs rather than 90 percent. This is not a cost-effective decision.

Recommendation 1: Fully Expand Medicaid to Cover More Georgians

Georgia can still take advantage of the full enhanced federal funding if lawmakers amend the Patients First Act to allow an eligibility increase up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. This decision would be economically responsible: Because of the federal agency’s decision, the cost of a partial expansion will be higher than a full expansion. Assuming that all 408,381 uninsured adults under 100 percent of poverty between ages 19-64 enroll in partial expansion and all 567,085 uninsured adults under 138 percent of poverty enroll in the full expansion, the state cost of a partial expansion is roughly $663 million compared to the full expansion state cost of $320 million.[4][5] This is an overestimate because not all of these uninsured Georgians will be eligible due to factors such as immigration status.

Georgia can still take advantage of the full enhanced federal funding if lawmakers amend the Patients First Act to allow an eligibility increase up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. This decision would be economically responsible: Because of the federal agency’s decision, the cost of a partial expansion will be higher than a full expansion. Assuming that all 408,381 uninsured adults under 100 percent of poverty between ages 19-64 enroll in partial expansion and all 567,085 uninsured adults under 138 percent of poverty enroll in the full expansion, the state cost of a partial expansion is roughly $663 million compared to the full expansion state cost of $320 million.[4][5] This is an overestimate because not all of these uninsured Georgians will be eligible due to factors such as immigration status.

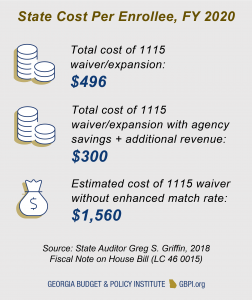

The difference of per-enrollee cost is even more stark, at $496 with a 90 percent match but $1,560 with the 67 percent match. When considering agency cost savings and additional revenue that comes with expanding Medicaid, the net cost for a full expansion amounts to only $300 per enrollee, and the net cost of full expansion drops from $320 million to $210 million.[6] Georgia’s best option, morally and economically, is to pass new legislation fully expanding Medicaid.

Use Waiver to Help Improve Substance Abuse and Mental Health Treatment

The federal administration indicated an interest in using 1115 waivers to provide tools to help states improve access to substance abuse treatment. About 1.3 million Georgia adults suffered with a diagnosed mental illness in the past year. Mental health conditions are often underdiagnosed and undertreated, making the likely scope of mental illness even broader. Though mental illness does not necessarily cause substance abuse, people with mental illness are more likely to experience a substance use disorder than people without one. Substance abuse problems are sharply on the rise, especially in Georgia’s mountain and rural areas. Drug overdose deaths in Georgia rose by 35 percent from 2012 to 2016, mainly due to the nationwide opioid epidemic. About 69 percent of overdose deaths in 2016 were related to opioids, including heroin and synthetic drugs such as oxycodone and morphine.[7]

To best take advantage of this flexibility, Georgia should provide Medicaid coverage for more adults. The state’s stringent eligibility requirements make it very difficult for low-income adults with substance use disorders (or at risk of developing a substance use disorder) to get Medicaid. Medicaid pays for mental health and substance abuse treatment, and the 1115 waiver can be used to cover more of these services, such as residential treatment.

Recommendation 2: Provide an Economic Boost for Enrollees, Instead of Penalizing Them

Recommendation 2: Provide an Economic Boost for Enrollees, Instead of Penalizing Them

One stated goal of Georgia’s waiver application process is “improving health outcomes by incentivizing work-related activities in Georgia’s Medicaid program.” On January 11, 2018, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services issued new guidance allowing states to make participation in work or other community engagement a requirement for certain adult Medicaid enrollees to maintain their eligibility.[8] Georgia lawmakers previously expressed interest in pursuing work requirements, and the Deloitte consultant team supported eight of the nine approved work requirement waivers.

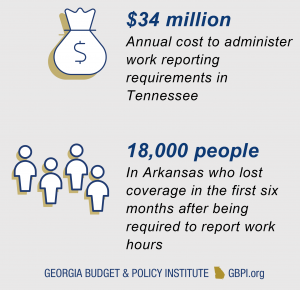

Work reporting requirements are not an effective way of getting more people connected to employment or volunteer activities, as shown in a recent study by Harvard researchers.[9] These requirements vary across states, but most require enrollees to report monthly or annually that they completed a qualifying activity for at least 80 hours a month.[10] Regular reporting puts an additional time and cost burden on state administrators and enrollees who are working or seeking work. Administering work reporting requirements often requires additional staff and updates to information technology systems.

Enrollees are typically given a few months to ensure all their paperwork satisfies the requirements or they will lose coverage. In some cases, they are locked out of coverage for the rest of the year. In Arkansas, 18,000 people lost coverage in the first six months after the work requirement policy was implemented.[11] Some enrollees reported not getting clear information about the requirements or had difficulty with the online account because of low computer literacy. People living in rural areas often did not have reliable internet access to use the online reporting portal. Others were working but had unpredictable hours or health conditions affecting their work or volunteering.[12]

Enrollees are typically given a few months to ensure all their paperwork satisfies the requirements or they will lose coverage. In some cases, they are locked out of coverage for the rest of the year. In Arkansas, 18,000 people lost coverage in the first six months after the work requirement policy was implemented.[11] Some enrollees reported not getting clear information about the requirements or had difficulty with the online account because of low computer literacy. People living in rural areas often did not have reliable internet access to use the online reporting portal. Others were working but had unpredictable hours or health conditions affecting their work or volunteering.[12]

Opportunity 1: Target Workforce Development that Does Not Jeopardize Access to Coverage

Research shows a relationship between unemployment and poorer health, but these studies do not imply that working leads to better health.[13] A person working in a low-quality job could in fact end up with poorer health. And if a person has poor health and no access to health care treatment, they may struggle to maintain employment.

About 60 percent of uninsured Georgians below the poverty line are employed. Others may be students or caregivers or have a disability but not receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Medicaid. Because most Georgians living in poverty are working, targeted efforts are a better approach to reach the smaller group that is not working.

Medicaid coverage also supports work. Medicaid expansion states saw their employment rates for workers with disabilities rise from 41 to 47 percent, while non-expansion states saw their rates decline from 43 percent to 41 percent.[14] Instead of pursuing work requirements, Georgia can help get more residents into quality employment by allowing enrollees to participate in a targeted workforce development initiative.

Case Study: Successful Targeted Work Promotion without Coverage Losses

Georgia can coordinate existing workforce development programs and enhanced state funding to link new Medicaid enrollees with training and work opportunities. Montana has been successful getting more of their new Medicaid expansion adults employed by investing in targeted outreach and personalized services. Montana’s HELP-Link is a voluntary workforce program for adults with Medicaid that provides “training and support to get more stable and higher paying employment in the long-term.”

The program increased labor force participation rates by 6 to 9 percent and 58 percent of employed enrollees reported higher wages in the year after completing the program. The median wage increase was $8,057 compared to the previous year. Most of the program is funded through existing workforce training funds, with additional support from state general funds.

Opportunity 2: Ensure People Can Afford to Use and Keep their Health Coverage

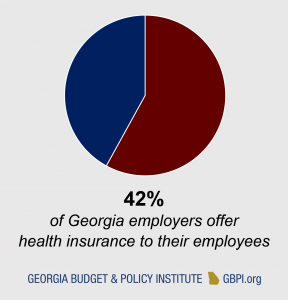

The state also aims to increase “the number of working Georgians who in turn can access health care coverage through employer-sponsored insurance.” However, only 42 percent of employers in Georgia offer a health insurance plan to their employees. Moreover, 23 percent of people are not eligible for an employee-sponsored plan, including people who are working part-time or in contract positions. These data suggest that not even an increase in the number of people working will get all workers access to health coverage. By accepting federal funding to extend coverage, working Georgians with low wages would now have an affordable option for health coverage. From there, the state can work on insurance regulations and marketplace options to make it affordable for more small businesses to provide health coverage.

The state also aims to increase “the number of working Georgians who in turn can access health care coverage through employer-sponsored insurance.” However, only 42 percent of employers in Georgia offer a health insurance plan to their employees. Moreover, 23 percent of people are not eligible for an employee-sponsored plan, including people who are working part-time or in contract positions. These data suggest that not even an increase in the number of people working will get all workers access to health coverage. By accepting federal funding to extend coverage, working Georgians with low wages would now have an affordable option for health coverage. From there, the state can work on insurance regulations and marketplace options to make it affordable for more small businesses to provide health coverage.

Medicaid traditionally does not allow states to charge premiums and permits only small co-payments. Some states are using 1115 waivers to add other conditions for new adult enrollees to keep their Medicaid coverage, such as imposing premiums and requiring the use of health savings accounts. Premiums and copayments can impede access to care, and collecting these fees require more administrative costs. A 2016 fiscal note in Georgia estimated the cost of a health savings account pilot program for a partial expansion population would cost the state $4.6 to $5.9 million in the first year and up to $7.5 to $9.8 million in the third year.[15]

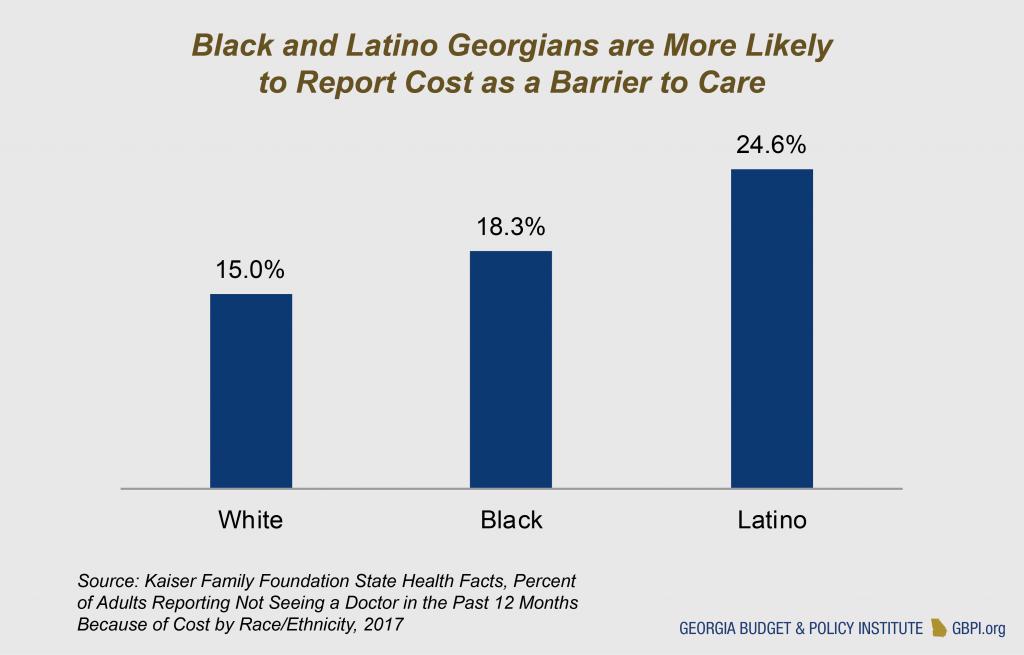

Cost of care is already a greater issue for Georgians than those in other states. Seventeen percent of Georgia adults reported not being able to see a doctor because of cost in the last 12 months, compared to the national average of 13.5 percent. Georgia can reduce cost barriers for residents by rejecting significant cost-sharing as a condition of keeping coverage.

Cost of care is already a greater issue for Georgians than those in other states. Seventeen percent of Georgia adults reported not being able to see a doctor because of cost in the last 12 months, compared to the national average of 13.5 percent. Georgia can reduce cost barriers for residents by rejecting significant cost-sharing as a condition of keeping coverage.

Recommendation 3: Provide Social Support to Improve Enrollees’ Health

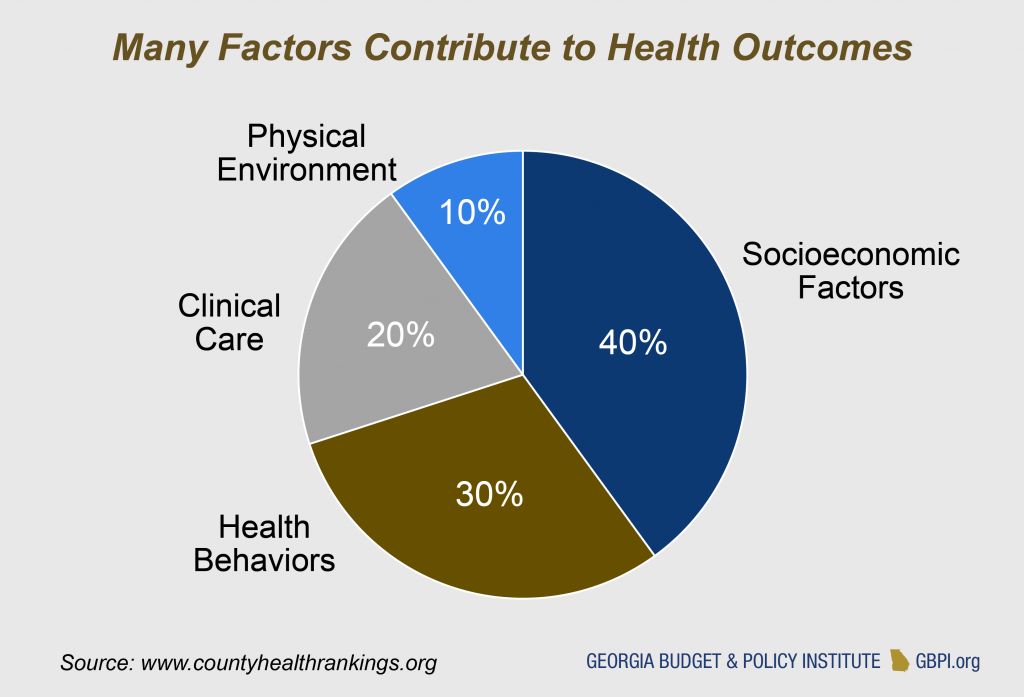

The health care sector is moving beyond a singular focus on clinical services to address other factors that influence health. Studies estimate medical care only accounts for 10 to 20 percent of health outcomes. Poverty, healthy food access, environmental quality and housing stability also affect health. Medicaid’s core purpose is to pay for direct health care services, but states can also use 1115 waivers to leverage Medicaid to connect people to health-related social services.

Georgia can help improve health outcomes in the state by expanding already-existing Medicaid transportation benefits and using the waiver to pay for services to help enrollees obtain safer housing and healthier foods. States are required to pay for transportation to appointments for Medicaid enrollees. Georgia can expand on this by considering ways to support transportation to other services such as job trainings. Medicaid 1115 waivers can also be used to require the organizations the state contracts with to provide coverage (managed care organizations) to refer enrollees to food-related supports such as SNAP and WIC or to support housing-related services. Medicaid cannot help pay for rent, but it can pay for help finding housing, education on tenant rights, assistance to prevent eviction and home safety modifications.[16] The federal administration is considering ways to allow states to pay for more social supports. For example, North Carolina’s recently-approved waiver allows Medicaid funds to pay for a range of health-related social services such as one-time payments for security deposits and first month’s rent.[17]

Georgia can help improve health outcomes in the state by expanding already-existing Medicaid transportation benefits and using the waiver to pay for services to help enrollees obtain safer housing and healthier foods. States are required to pay for transportation to appointments for Medicaid enrollees. Georgia can expand on this by considering ways to support transportation to other services such as job trainings. Medicaid 1115 waivers can also be used to require the organizations the state contracts with to provide coverage (managed care organizations) to refer enrollees to food-related supports such as SNAP and WIC or to support housing-related services. Medicaid cannot help pay for rent, but it can pay for help finding housing, education on tenant rights, assistance to prevent eviction and home safety modifications.[16] The federal administration is considering ways to allow states to pay for more social supports. For example, North Carolina’s recently-approved waiver allows Medicaid funds to pay for a range of health-related social services such as one-time payments for security deposits and first month’s rent.[17]

Other social supports that can improve health include supported housing, supported employment and peer support coaches. Supported housing is a model for bringing together housing assistance and health services; supported employment helps people find and keep employment while receiving health services. The state’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities currently provides these services for a limited number of people with disabilities, mental illness or substance abuse disorders. Georgia can expand on this work by using the Medicaid waiver to provide support and treatment services to more adults with substance use disorders.

Case Study: Funding Connections to Health-Related Social Supports to Improve Patient Health

North Carolina received 1115 waiver approval on October 19, 2018 for a pilot project to assess Medicaid enrollees’ non-medical needs and pay for services to address these needs. The state is expected to serve between 25,000 and 50,000 residents in two to four geographic areas of the state. The services are focused on housing instability, transportation barriers, interpersonal violence, toxic stress and food insecurity. Examples of services provided through the network of organizations include:[18]

- Modifications to housing, such as mold removal for asthma patients;

- Transportation vouchers for a diabetes patient to get to a pantry or store with healthy food options; and

- Connection to domestic violence shelters or services for a patient experiencing intimate partner violence that contributes to their high blood pressure.

Summary of Recommendations

The news that the federal government will only fund 67 percent of the cost of partial Medicaid expansion has shifted the conversation around Medicaid in Georgia. The Patients First Act envisioned the Medicaid 1115 waiver working together with the 1332 waiver to address the needs of Georgians making below 138 percent of the poverty line. These are the Georgians who would be eligible for coverage under a full Medicaid expansion but not partial expansion. With recent news confirming the state will not receive a 90 percent federal match to pay for the partial Medicaid expansion, Governor Kemp’s team may take a greater interest in the 1332 waivers because the partial expansion is not financially feasible. The state can still create a Medicaid waiver plan to increase access to care and promote better health by pursuing the following recommendations:

- Recommendation 1: Fully Expand Medicaid to Cover More Georgians

- Recommendation 2: Provide an Economic Boost for Enrollees, Instead of Penalizing Them

- Recommendation 3: Provide Social Support to Improve Enrollees’ Health

Endnotes

[1] Georgia Department of Community Health (2019). 2019 Financial Limits – All Programs. Retrieved from https://medicaid.georgia.gov/sites/medicaid.georgia.gov/files/related_files/site_page/2019%20Financial%20Limits%20revised%2022119.pdf

[2] Kaiser Family Foundation (2019). Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/b46603c/

[3] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2019). CMS Statement on Partial Medicaid Expansion Policy. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-statement-partial-medicaid-expansion-policy

[4] Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (2019, August 30) calculations based on uninsured population estimates from Deloitte Consulting LLP (2019). Georgia Department of Community Health Waiver Project: Georgia Environmental Scan Report. Retrieved from https://medicaid.georgia.gov/sites/medicaid.georgia.gov/files/related_files/document/GA%20Waiver_Georgia%20Environmental%20Scan%20Report_07082019.pdf

[5] Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (2019, August 30) calculations based on cost estimates from State Auditor Greg S. Griffin (2019). Fiscal Note House Bill (LC 46 0015). Retrieved from https://opb.georgia.gov/sites/opb.georgia.gov/files/related_files/site_page/LC%2046%200015.pdf

[6] Kanso, D. (2019). Senate Bill 106: Medicaid Waivers Could Reshape Georgia’s Health Care System & State Budget. Retrieved from https://gbpi.org/2019/medicaid-waivers-could-reshape-georgias-healthcare/

[7] Tharpe, W. (2018). People-Powered Prosperity. Retrieved from https://gbpi.org/people-powered-prosperity/

[8] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2018). RE: Opportunities to Promote Work and Community Engagement Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd18002.pdf

[9] Sommers, B. D., Goldman, A. L., Blendon, R. J., Orav, E. J., & Epstein, A. M. (2019). Medicaid Work Requirements — Results from the First Year in Arkansas. New England Journal of Medicine. doi: 10.1056/nejmsr1901772

[10] National Academy for State Health Policy (2019). A Snapshot of State Proposals to Implement Medicaid Work Requirements Nationwide. Retrieved from https://nashp.org/state-proposals-for-medicaid-work-and-community-engagement-requirements/

[11] Rudowitz, R., Musumeci, M., & Hall, C. (2019). February State Data for Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-data-for-medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas/

[12] Musumeci, M., Rudowitz, R. & Lyons B. (2018). Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience and Perspectives of Enrollees. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas-experience-and-perspectives-of-enrollees/

[13] Antonisse, L. & Garfield, R. (2018). The Relationship Between Work and Health: Findings from a Literature Review. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-relationship-between-work-and-health-findings-from-a-literature-review/

[14] Hall, J. P., Shartzer, A., Kurth, N. K., & Thomas, K. C. (2018). Medicaid Expansion as an Employment Incentive Program for People With Disabilities. American Journal of Public Health, 108(9), 1235–1237. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304536

[15] State Auditor Greg S. Griffin (2016). Fiscal Note House Bill (LC 33 6665). Retrieved from https://opb.georgia.gov/sites/opb.georgia.gov/files/related_files/site_page/LC%2033%206665-Expand%20Medicaid%20100%25%20FPL.pdf

[16] American Hospital Association (2019). Medicaid Financing for Interventions that

Address Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved from https://www.aha.org/system/files/2019-01/medicaid-financing-interventions-that-address-social-determinants-of-health.pdf

[17] Abrams, A. (2019). Using Medicaid Dollars to Pay for Housing? Retrieved from https://shelterforce.org/2019/02/19/medicaid-dollars-for-housing/

[18] Healthy Opportunities Pilots Fact Sheet, Healthy Opportunities Pilots Fact Sheet (2018). Retrieved from https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/SDOH-HealthyOpptys-FactSheet-FINAL-20181114.pdf