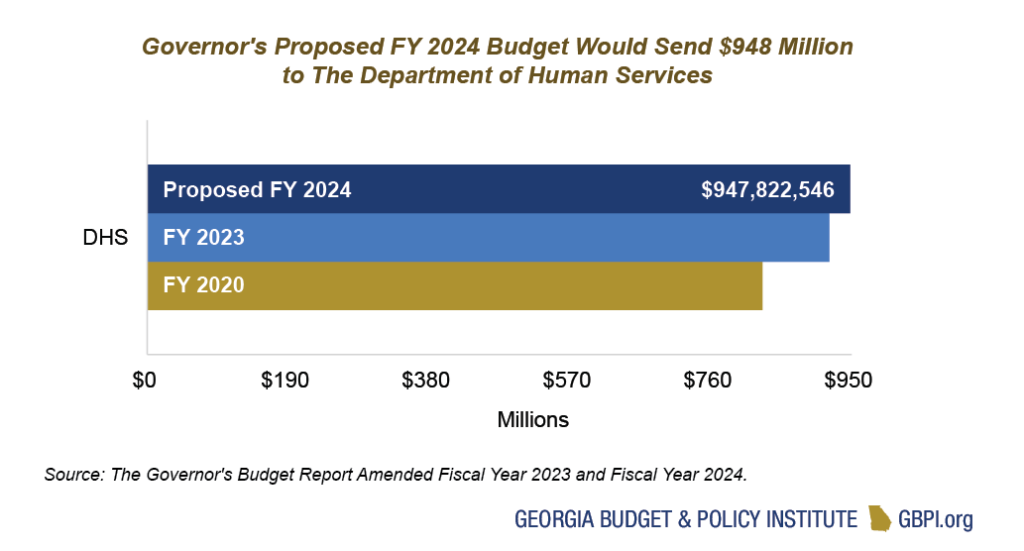

Gov. Brian Kemp’s proposed $948 million Department of Human Services (DHS) budget for the 2024 fiscal year includes cost of living adjustments (COLA) for state workers and hiring hundreds of DFCS eligibility workers.[1] The Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 proposal increases investment in the agency by $28 million more than the budget lawmakers approved last year. More than half of the recommended increase over the agency’s FY 2023 budget is from the $2,000 COLA for all qualified full-time state employees. The governor’s proposal is about $118 million more than the FY 2020 budget, which legislators passed before the start of the pandemic.

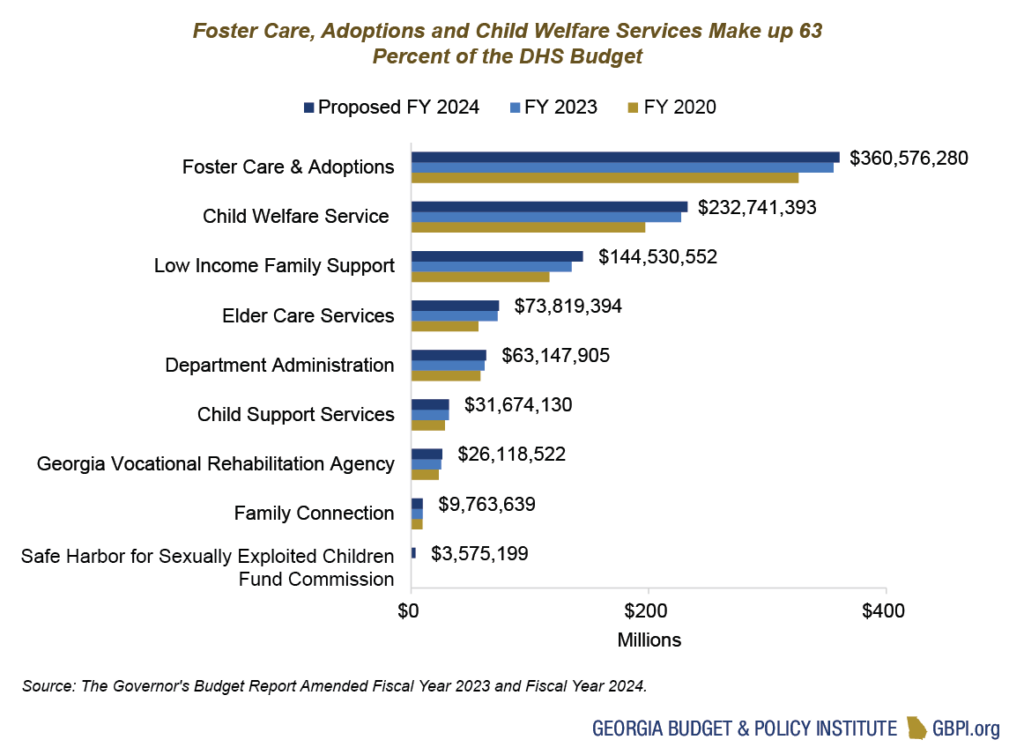

The agency’s largest share of state funding is for child welfare- and foster care- and adoption-related services. The Georgia Division of Family and Children Services’ (DFCS) efforts to protect and support vulnerable children account for about 63 percent of the agency’s overall budget. The next biggest share of spending is federal low-income assistance programs such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Those programs account for 15 percent of the agency’s budget. Smaller programs such as elder care services, child support services and vocational training for adults with disabilities account for the remaining funds.

Most of DHS’ programs support people and families with low incomes and protect groups at risk of neglect or abuse. Many of the people participating in DHS programs are Black and Brown families. For example, Black Georgians are the single largest group receiving SNAP and TANF. Black, multiracial and white children are overrepresented in the state’s foster care system.[2] However, among the children who cannot reunite with their families, white children are more likely to have an adoptive parent identified than children of color.[3] DHS’ budget allocation is a racial justice issue, where investment, or lack thereof, disproportionately impacts the well-being of Black and Brown people.

By the Numbers

Amended 2023 Fiscal Year Highlights

$8.5 million in additional state funds for AFY 2023, including:

- $5.8 million increase for a quality assurance management consultant

- $2 million for technology improvements

- $662,433 increase for hiring 80 additional Medicaid eligibility supervisors and caseworkers

2024 Fiscal Year Highlights

$27.8 million in additional state funds for FY 2024 including:

- $15.4 million increase in pay for full-time state employees

- $3.2 million increase to help hire 300 additional Medicaid eligibility caseworkers

- $3.4 million increase to the Safe Harbor for Sexually Exploited Children Fund Commission

Workforce Continues to Be the Salient Issue

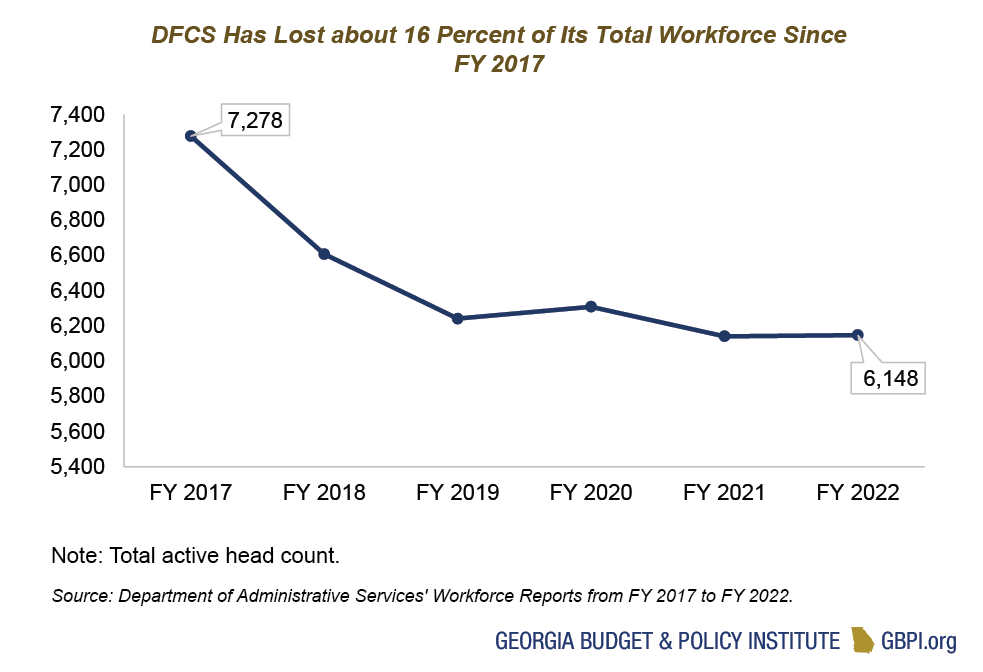

Years of lawmakers’ disinvestment in the state government’s workforce contributed to the current staffing crisis. The result is weaker services provided to Georgians, especially Georgians of color who engage with certain government agencies at disproportionate rates. According to the Department of Administrative Services (DOAS), the Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) within DHS has a higher turnover rate, 30.3 percent, than the state government as a whole. Between FY 2017 and FY 2022, DFCS lost 16 percent of its workforce.[4]

This year holds significant challenges for DFCS. They must reconsider the eligibility for millions of Medicaid and SNAP recipients as pandemic-era eligibility expansions end. For Medicaid in particular, more than half a million people are at risk of losing coverage, and Black and Brown children are most likely to lose health care access. Many may be denied coverage not because they are ineligible but for administrative reasons.[5]

The governor’s intent to hire more than 300 eligibility staff and increase salaries by $2,000 are positive steps but they don’t go far enough. Many become eligibility caseworkers because they want to help their fellow Georgians, but the pay is low. In FY 2017, the entry-level pay for an eligibility worker was $25,722.[6] In FY 2023, their entry-level pay is $32,000.[7] That’s only about a two percent increase over the past six years considering inflation and it’s still among the lowest base salaries in DFCS. Additionally, some caseworkers have expressed that the pay is often not worth the high workload, long hours and stress of the job.[8] Medicaid unwinding will only make the job harder for eligibility staff. Pay is a key factor in not just recruiting but retaining more staff, which would reduce workloads, ease stress, strengthen morale and improve the accuracy of eligibility determinations.

Lawmakers can invest in eligibility workers in two ways: (1) In the short term, they can include resources in the FY 2024 budget to continue the bonuses that ended in December of last year. (2) For a long-term solution, the legislature should approve a pay increase for DFCS eligibility workers like they did for child welfare caseworkers in 2017. These investments support the caseworkers and the Georgians relying on them to approve and administer critical assistance.

End Notes

[1] Office of Planning and Budget. January 2023. AFY 2023 and FY 2024 governor’s budget report. https://opb.georgia.gov/budget-information/budget-documents/governors-budget-reports.

[2] Department of Human Services. September 30, 2022 [last quarter reported]. Child welfare data: Foster care. https://dhs.georgia.gov/division-family-children-services-child-welfare

[3] Department of Human Services. January 24, 2024. Child welfare data: Children available for adoption. https://dhs.georgia.gov/division-family-children-services-child-welfare

[4] GBPI analysis of workforce data from Department of Administrative Services’ Workforce Reports from FY 2017 to FY 2022. https://doas.ga.gov/human-resources-administration/hr-tools/workforce-reports.

[5] Chan, L. (2022, October 26). Keeping Georgians covered: Tools for minimizing the harm of the Medicaid unwinding. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/keeping-georgians-covered-tools-for-minimizing-the-harm-of-the-medicaid-unwinding/.

[6] Voices for Georgia’s Children. (2018, December 4). Turnover rates and average salaries of child-serving workers.

[7] Voices for Georgia’s Children. (2022). State agency salaries for child-serving workers. https://georgiavoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1.-State-Agency-Salaries-for-Child-Serving-Workers-FINAL.pdf.

[8] Suro, P. (2022, December 7). DFCS worker speaks out citing employees are overworked and burned out. 11Alive WXIA Atlanta. https://www.11alive.com/article/news/local/dfcs-worker-speaks-out-citing-employees-are-overworked-and-burned-out/85-d3b66cd2-f6d0-44f2-8df9-5ecdfcf04aa7; Landergan, K. (2023, February 3). DFCS caseworkers in Georgia: ‘It’s like being in an emergency room.” Atlanta Journal Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-news/dfcs-caseworkers-in-georgia-confront-chaos-its-like-being-in-an-emergency-room/M6VEWIPZZFGJ5BAX2F264UVKAA/