More funding directed to economically-disadvantaged students helps them do better in school and in life. Gov. Nathan Deal’s Education Reform Commission recognized this and directed extra funds to school districts for these students in its proposed revision to Georgia’s funding formula for K-12 schools. This recognition is a step forward but it falls far short of meeting their needs. The commission recommends new criteria, detailed in our recent report “Student Success in the Balance: Update for 2017” to identify Georgia’s low-income students that cut their count nearly in half. The extra $1.29 per day for each student proposed by the commission will not go far either. The General Assembly can fix these shortcomings by using less restrictive criteria to identify low-income students and increasing the supplemental funds for these students from $232 per year to at least $600.

Money Matters for Low-Income Students

Students who grow up in low-income families often face challenges that stifle their ability to learn, such as hunger, stressful family situations and limited chances to develop strong literacy skills. Sustained increases in funding for these students help educators respond to these challenges and lead to better outcomes for them. When funding increases, these students:

- Stay in school longer

- Are more likely to complete high school

- Earn higher wages as adults

- Have higher family incomes as adults

- Are less likely to be poor[i]

Gains for students are also gains for the state as it seeks to build an educated workforce that can attract and grow high-wage industries. The governor’s Complete College Georgia and High Demand Career initiatives both identify the need for Georgia to strengthen its pipeline of talent to fill the high-skill jobs of the future. As a state where many families struggle to make ends meet, Georgia can’t reach those goals unless students from modest backgrounds are given better opportunities to thrive.

The Number of Students Counted as Low-Income Plunges Under New Definition

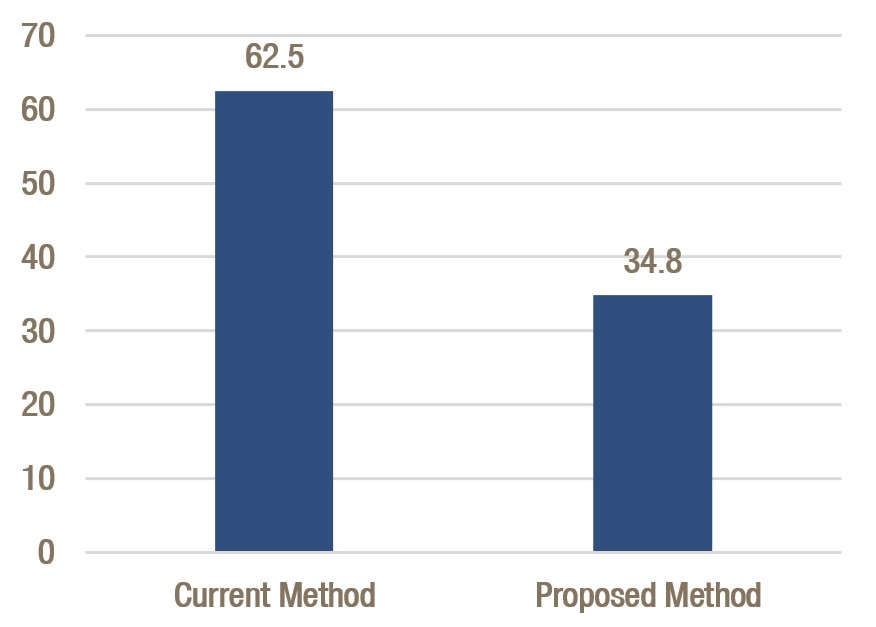

Over 62 percent, or more than 1 million, of Georgia’s public school children are considered economically disadvantaged today because they participate in the federal free and reduced-price lunch program, the benchmark used nationally to identify these students. Students receive free lunches if their families’ income is up to 130 percent of the federal poverty line, or about $26,000 for a family of three. Students get a reduced price lunch if their families earn between 131 and 185 percent of the poverty level, or up to about $37,000 for a family of three.

The commission’s recommendations call for more restrictive criteria to determine who qualifies as low-income to reflect changes to the federal lunch program. Under the new criteria, students will be considered economically disadvantaged if they:

- Live in a family receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (SNAP) benefits, also known as food stamps

- Live in a family receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits

- Are identified as homeless

- Are identified as living in foster care

- Are identified as migrant

Under these proposed criteria, the percentage of Georgia’s students counted as economically disadvantaged is cut nearly in half, to just 35 percent from about 63 percent.

The proposed criteria create much lower income caps than is now the case. A family of three in Georgia can earn no more than about $9,400 annually to qualify for the TANF program, which provides cash benefits. The state also limits SNAP eligibility to families with incomes up to 130 percent of the federal poverty line, well below the threshold in many other states including Florida, North Carolina and Texas.

The commission’s recommendations exclude entirely students identified now whose family incomes fall between 131 and 185 percent of the poverty level. These children and their families still face economic hardships including food insecurity, residential instability, lack of health insurance and disconnected utilities due to inability to pay.[ii] These challenges harm children’s well-being and can negatively impact their success in the classroom.

New Way to Identify Poor Students Yields Steep Decline

The General Assembly can use a broader definition of economically disadvantaged students to ensure all children whose families struggle financially get the support needed to succeed in school. One option is for local districts to collect basic income data on students’ families, so that they can determine if children qualify as low-income under current definitions.

The General Assembly can use a broader definition of economically disadvantaged students to ensure all children whose families struggle financially get the support needed to succeed in school. One option is for local districts to collect basic income data on students’ families, so that they can determine if children qualify as low-income under current definitions.

Extra Funds Won’t Go Far

The supplemental funding allocated to economically disadvantaged students is low at $232 annually or $1.29 per day. This is likely not enough to provide the services that help these students succeed. Those include small class sizes, more time to learn though longer school days or years, and one-on-one or small group instruction.

The General Assembly can increase the supplemental funds for these students to at least $600 to improve their chances for success. This is the amount lawmakers would allocate if the commission stuck with the funding weight it first considered for economically disadvantaged students. Using this weight also sets Georgia roughly in line with the national average for this type of extra support. Given what’s at stake for them and the state’s need to prepare students to be skilled members of the workforce, this is an investment worth making.

[i] Jackson, C. K., Johnson, R.C., & Persico, C. (2016) The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms, The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 157-218.

[ii] Gershoff, E. T., Aber, J. L., Raver, C.C., & Lennon, M. C. (2007) Income is Not Enough: Incorporating Material Hardship Into Models of Income Associations with Parenting and Child Development, Child Development. 78(1) 70-95.