Trimming Georgia’s income tax rate is a hot topic of late and will likely be debated during the 2014 election season and next year’s General Assembly. But a recently released report by the nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) about what is happening in Kansas should throw up a big “caution!” sign in front of Georgia lawmakers and voters.

Trimming Georgia’s income tax rate is a hot topic of late and will likely be debated during the 2014 election season and next year’s General Assembly. But a recently released report by the nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) about what is happening in Kansas should throw up a big “caution!” sign in front of Georgia lawmakers and voters.

The report examines the economy, budget and tax revenue trends in Kansas, often cited by anti-tax activists as the model for how states can cut income taxes in pursuit of a so-called “fair tax” or “pro-growth” tax policy. In May 2012, Kansas’ governor signed perhaps the largest package of income tax cuts any state ever enacted in the aftermath of a recession. More cuts are scheduled to occur over the next several years.

Kansas’ governor and other supporters of the cuts say they are part a long-term plan to eventually eliminate the Sunflower State’s income tax altogether, arguing that would deliver “a shot of adrenaline into the heart of the Kansas economy.” That claim is also making the rounds in Georgia. But as the report highlights, Kansas’ anti-tax agenda is failing to live up to the hype.

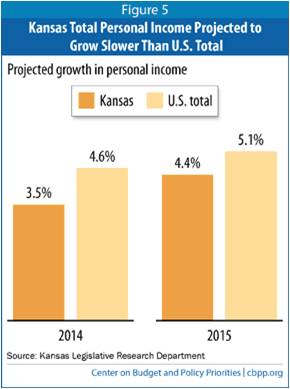

Since the tax cuts began in 2013, Kansas added jobs at a modestly slower pace than the country as a whole. The annual incomes of typical Kansas families also lagged behind the national average, and earnings for Kansas workers declined during 2013. Personal income growth is also expected to lag behind there in the next two years and future job growth will probably be “relatively modest,” according to Kansas experts.

Since the tax cuts began in 2013, Kansas added jobs at a modestly slower pace than the country as a whole. The annual incomes of typical Kansas families also lagged behind the national average, and earnings for Kansas workers declined during 2013. Personal income growth is also expected to lag behind there in the next two years and future job growth will probably be “relatively modest,” according to Kansas experts.

The tax cuts haven’t seemed to spur business growth, either. The number of registered businesses in Kansas grew more slowly last year than in 2012, and Kansas’ share of all U.S. business establishments fell over the first three quarters of 2013, the most recent data available. That’s not surprising. State income taxes have little effect on a state’s overall economy or attractiveness to businesses, according to the vast majority of experts.

In contrast to their negligible economic returns, the Kansas tax cuts are exacting a high toll on the state’s public services. The cost to the state’s general fund is $495 million this year, or 8 percent of the revenue it could use to pay for schools, health care and other public services. That’s a massive blow to the state’s core investments. For example, Kansas’ third largest school district closed three schools, expanded class sizes, cut music programs and eliminated hundreds of staff positions. Universities saw state funding per student fall by 3 percent from 2012 to 2013, while tuition rose by 8 percent.

Georgia is home to more people than Kansas and has a much larger annual budget, so similar shortfalls here would be more extreme. An 8 percent hit to Georgia’s general fund budget for the upcoming 2015 fiscal year would equate to about $1.5 billion in lost revenue. That’s about three-quarters of what Georgia spends each year on universities and about three times its entire budget for human services.

Georgia voters can expect to hear a lot about income taxes from candidates as the election season kicks into high gear. Ballots in November will ask voters if Georgia should cap the state’s income tax at six percent, a first step on the troublesome path Kansas is following.

Georgia voters should answer, “no.” Cutting or eliminating state income taxes might sound tempting at first blush. But Georgians should carefully consider lessons offered by Kansas, where the breezy promises of tax cut cheerleaders are proving empty. If Georgia takes a page from the Kansas playbook, the outcome is unlikely to be any better.