The widening gap between rich and poor makes it harder for state lawmakers to fully fund education, health care and other vital services, more so in states like Florida and Tennessee that rely mostly on sales taxes. That’s one of the main findings of a new study from Standard & Poor’s, a widely-respected, independent agency. S&P is one of three groups who determine Georgia’s bond rating, which affects whether taxpayers get a good deal on capital investments like new roads and university buildings.

The widening gap between rich and poor makes it harder for state lawmakers to fully fund education, health care and other vital services, more so in states like Florida and Tennessee that rely mostly on sales taxes. That’s one of the main findings of a new study from Standard & Poor’s, a widely-respected, independent agency. S&P is one of three groups who determine Georgia’s bond rating, which affects whether taxpayers get a good deal on capital investments like new roads and university buildings.

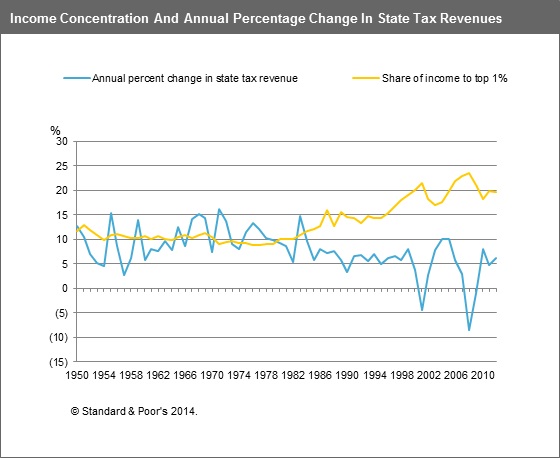

The report details how rising inequality over recent decades coincided with slower revenue growth in states across the country, including Georgia. Simply put, as the wealthy capture more and more of the economic pie over time, states collect less money from taxpayers.

- Nationwide, the share of U.S. income going to the top 1 percent doubled from 1980 to 2011 (from about 10 percent to 20 percent), while states’ average rate of yearly revenue growth was cut in half (from nearly 10 percent to below 5 percent).

- In Georgia, revenues grew by nearly 11 percent a year from 1950-1979, on average, compared to less than 3 percent a year from 2000 to 2009. Meanwhile, the share of Georgia’s yearly income taken home by the top 1 percent nearly doubled to 18.7 percent in 2007 from 9.5 percent in 1979, according to data from a separate report.

The reasons behind these trends are intuitive. State revenue comes mostly from income and sales taxes, unlike local governments that rely heavily on property taxes. But the wealthy are often able to shield part of their income from taxes, and the amount of untaxed income grows as they take home a larger share of the economy over time. Inequality also leads to lower sales tax revenue since it shrinks the amount working families have available to spend. Mid- and low-income families tend to pump most of what they earn back into the economy, unlike the wealthy who are more able to save.

Inequality’s effect on both income and sales taxes explains why almost all states are struggling with slower revenue growth, according to the report. But the authors also explain states that rely too heavily on sales taxes are at higher risk than states with more balanced revenue streams that include income taxes. They compared ten states that are relatively dependent on income taxes, including Georgia, to ten states more reliant on sales taxes.

What they found indicates that states with graduated income taxes can counteract some of the harm imposed by inequality. By applying progressively higher rates to higher earners, income-taxing states are able to collect more revenue from people at the very top who are reaping most of the gains from today’s economy. But because inequality dampens economic growth and squeezes workers’ wages, states linked too closely to the sales tax can see their revenues flat-line. A family with paychecks that aren’t growing is unlikely to boost spending much, even if the economy as a whole is improving.

What does this mean for Georgia? It means that plans to eliminate or drastically cut the state’s income tax in exchange for higher sales taxes would probably make the problem even worse. An adequate and reliable source of funding is critical for Georgia lawmakers to fully fund education, health care and investments in the future like transportation. But rising inequality means that shifting further toward sales taxes runs counter to that goal, putting the state at risk of falling revenues and possibly higher borrowing-costs if its bond rating drops.