This report was written in partnership with Jyll Walsh, GBPI doctoral intern.

Early care and education (ECE) centers play an integral role in the health and well-being of many children and families in Georgia. The holistic approach ECE centers can provide has shown to have a substantial, lasting and even intergenerational impact on health and well-being, and has the strongest effect on children from families with low incomes.

The Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning (DECAL) is responsible for meeting the early care and education needs of Georgia’s children and their families. It manages Georgia’s pre-K program, licenses ECE centers and home-based child care, administers Georgia’s Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) Program and federal nutrition programs and oversees the quality child care rating system. The department also houses the Head Start State Collaboration Office, which is charged with enhancing the quality and availability of child care, and works collaboratively with Georgia Child Care Resource and Referral (CCR&R) agencies and organizations throughout the state to enhance early care and education. The FY 2021 state budget allots $54.2 million for DECAL, a $7.3 million reduction from the previous year and $379 million in lottery revenue to fund Georgia’s pre-K program.[1]

“We are able to provide child care for our child, but it comes at the expense of our quality and quantity of work as well as our mental and physical care. It does not feel sustainable.” – Respondent to 2020 parent survey conducted by GEEARS

As some Georgians were not able to work remotely and others are beginning to trickle back to work, the child care shortage is troubling news for the economy and the health and well-being of working families. The most disproportionate impact is on low-wage workers and people of color, who shoulder some of the most severe financial and health burdens associated with the pandemic yet are some of the first workers called back to job sites. This is especially true for low-income parents raising young children, who are six times less likely to be able to work from home than higher-wage workers. It is also true for Black and Hispanic workers, with less than one in five Black and one in six Hispanic workers able to telework. And statistics show that only 34.9 percent of working parents with young children from all income levels can telework.[5]

Families are not the only ones in survival mode. The ECE industry, which typically has slim profit margins, now faces huge losses of revenue against high fixed costs and new health and safety expenses. And with no statewide closure protocols, it is up to the individual ECE centers to balance the health and livelihood of their business, staff and families they serve. A recent analysis by the Center for American Progress showed that without additional financial assistance, 50 percent of the country’s child care centers will close permanently, leading to a loss of 4.5 million child care slots. Moreover, 29 percent of surveyed centers in Georgia stated they could not survive closing for more than two weeks without significant public investment.[6]

The federal CARES Act provided $144,237,467 to assist ECE centers throughout Georgia to avoid closures, supply personal protective equipment (PPE) to open centers and create an accessible critical child care network for essential workers.[7] This federal relief is insufficient; it is estimated Georgia needs an additional $2 billion in the upcoming federal relief package. Adequate ECE relief funding is an essential part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recovery efforts.

How Early Childhood Education Benefits Health and Well-being

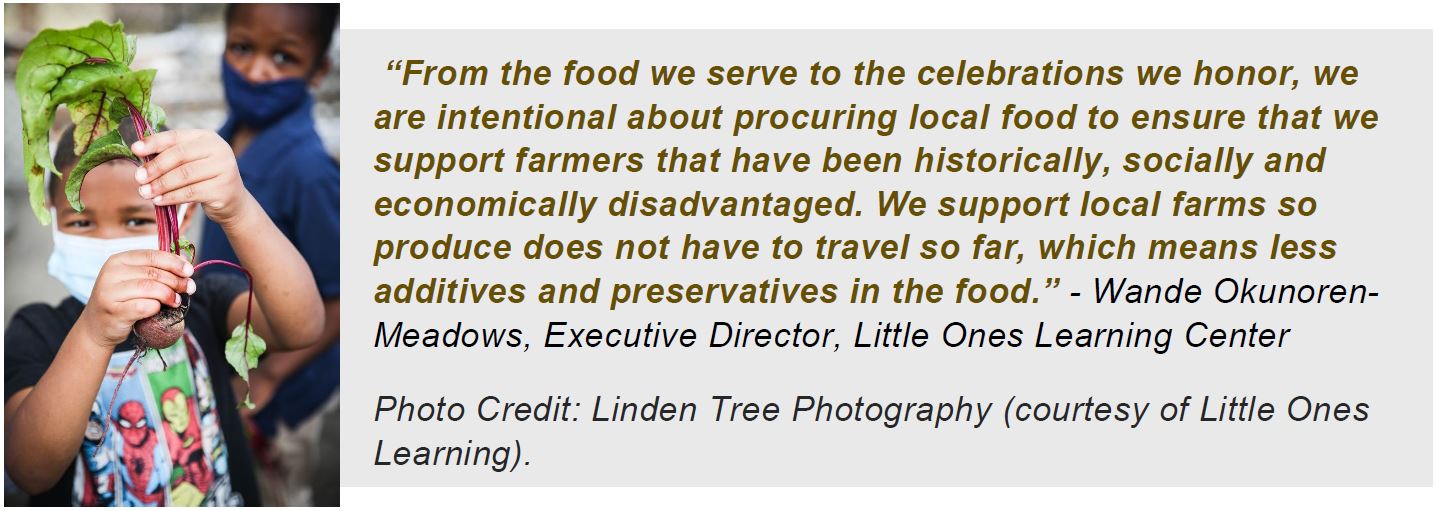

Helping parents engage in the workforce is a foundational piece of what ECE centers facilitate, but child care does much more to help children and families thrive. Their services are aimed at producing children who are healthy, ready for kindergarten, have access to proper nutrition, are socially and emotionally competent, and ECE centers offer family support services. Also, ECE centers and pre-K programs that are licensed through Georgia DECAL are provided funding or other incentives to implement wellness policies, programs for healthy habits in caregivers, the Georgia Farm to Preschool program, physical and nutrition education and more.

Access to Nutrition

Access to Nutrition

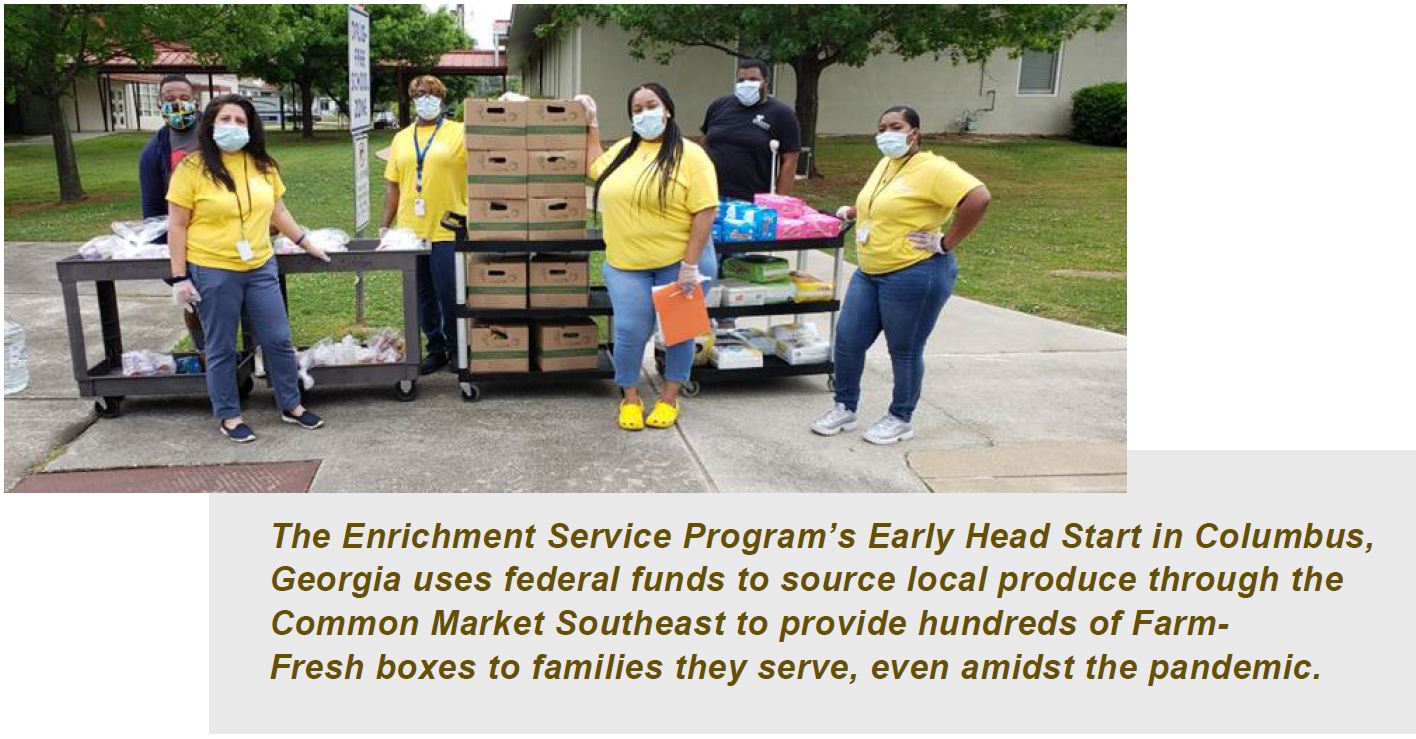

A key aspect of child well-being is the availability of nutritious food. The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP)

and the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) are federal funds ECE centers can use to ensure children and adults throughout the state have access to nutritious meals both in the child care setting and at home. These funds work by targeting counties with high rates of food insecurity and adult obesity.

Despite closures, ECE centers have been able to continuously provide food to families. By accessing federal funds, ECE centers reduce hunger and malnutrition and put money into the local economy.

Resources that Promote Health

As a central point of contact to families with children aged birth to five, ECE centers are a health and well-being resource hub, providing direct services or referrals such as health care navigation, developmental screening and infant and early childhood mental health.

- In 2019, Head Start and Early Head Start programs increased the number of all children who were up-to-date on a schedule of age-appropriate preventive and primary health care from 46 percent at enrollment to 84.6 percent by the end of the year. Many Head Start and Early Head Start programs have a Mental Health Specialist or Licensed Counselor to promote social and emotional competence in children and support families with issues such as substance abuse, domestic violence or stress.

- Babies Can’t Wait (BCW) provides early developmental screenings to young children and assists in coordinating any early intervention. This program is integrated into many ECE programs; the early detection and treatment of developmental and intellectual disabilities can help improve outcomes for children and their families. Since early educators commonly refer families to BCW, the number of children being screened has decreased during the pandemic.

- ECE centers work with community partners to provide home visiting services or in-house parent education aimed at teaching parenting skills that build their children’s social-emotional competence, physical health and early brain development. These evidence-based programs are highly effective, but there is limited availability. Home visiting programs are only in 20 counties across Georgia.

Although the ability and requirements of ECE centers to serve as health and wellness advocates varies by funding source, all programs and parents have access to Child Care Resource and Referral agencies (CCR&Rs). CCR&Rs help parents and professionals navigate additional sources of public assistance. The majority of CCR&Rs are equipped to connect individuals with resources such as housing assistance, health insurance programs and child care tax credit information.

Access to Child Care and Early Education

The average yearly cost of ECE in Georgia is over $15,000 for two children, which amounts to half the total annual income of a family living in poverty.[8] While assistance is available in all 159 counties, it is not enough to serve all of the estimated 364,000 eligible children in low-income working families who need it.[9]

| What ECE Programs are Available to Support Georgia’s Working Families? | ||||

| Program | Age Served | Cost | Annual Capacity | Access/Eligibility |

| Early Head Start | 0 to 2 years-old | None | ~5,000 children | 100% of federal poverty level (FPL) ($26,200 annually for a family of 4); there is a waitlist and very few programs in area |

| Head Start | 3 to 5 years-old | None | ~19,500 children | 100% FPL; there is a waitlist and are few programs in area |

| Immigrant & Seasonal Head Start | 0 to 5 years-old | None | ~360 children | 100% FPL; only 4 locations in the state |

| Program | Age Served | Cost | Annual Capacity | Access/Eligibility |

| GA State-Funded Pre-K | 4 to 5 years-old | None | ~80,000 children | Any four-year-old who is a resident in the state; however, there are over 4,000 children on the waitlist due to capacity |

| Licensed Child Care Programs | 3 months and up | ~$8,000/ year per child | Market-Driven | Subsidies (CAPS) are provided to 75,000 children annually; however, about 48,000 children were declined in 2019 due to limited capacity and/or ineligibility |

Note: Citizenship is not required for any program eligibility

Sources: Georgia’s Cross Agency Child Data System (2019); Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning, Bright from the Start 2019 Annual Report; GBPI 2021 Georgia Budget Primer, p. 37.

Georgia Pre-K

One of the most widely recognized and utilized programs is Georgia Pre-K, which is funded through the state’s lottery revenues. Although touted as a universal program, serving over 80,000 of Georgia’s four-year-olds at no cost annually, it is not able to provide space for every eligible applicant. There are currently about 4,000 children on the waiting list.

Enrollment of children from low-income families in Georgia state-funded pre-K programs varies greatly by county. In all, only 30 percent of eligible children from low-income families across the state are enrolled.[10] Stagnant funding keeps Georgia’s pre-K program from expanding.[11] Georgia provides less per student in the program than the state did a decade ago. In FY 2011 Georgia allocated the equivalent of $5,050 per student. When taking inflation into account, that is $352 more than in the current budget cycle.

Head Start and Early Head Start

Head Start and Early Head Start (HS/EHS) exclusively serve families with low incomes and focus on child and family well-being as a core component. By engaging with parents and community partners, HS/EHS works to connect families with primary medical homes, oral health, mental health and substance abuse treatment resources.

There are over 160,000 children under age five living at or below poverty in Georgia; however, the program currently only has capacity for approximately 25,000 children annually. The program prioritizes children with special needs and disabilities.[12]

Private Early Care and Education

Outside of fully funded programs, child care is provided in a variety of settings: licensed child care learning centers, exempt providers (such as school-based or faith-based child care programs), licensed family child care learning homes and informal child care providers.

The Child Care and Parents Services (CAPS) program supports early education by providing child care subsidies to low-income families while they work, go to school or trainings or participate in other work-related activities. In FY 19, the CAPS program provided over 75,000 children subsidies to attend child care. For that year they renewed 27,000 scholarships and reviewed over 82,000 new CAPS applications. This means about 48,000 children whose parents were seeking child care support were not accepted into the CAPS program due to limited capacity or ineligibility.[13]

These federal funds are also intended to enhance the quality and availability of child care across Georgia. Providers accepting CAPS are reimbursed more per child if they are Quality Rated, a credentialing program where providers work to deliver higher levels of care, education and well-being services to children and families. DECAL is currently working to assist child care centers who accept CAPs to also participate in the Quality Rated program; however, not all centers will qualify for assistance.[14]

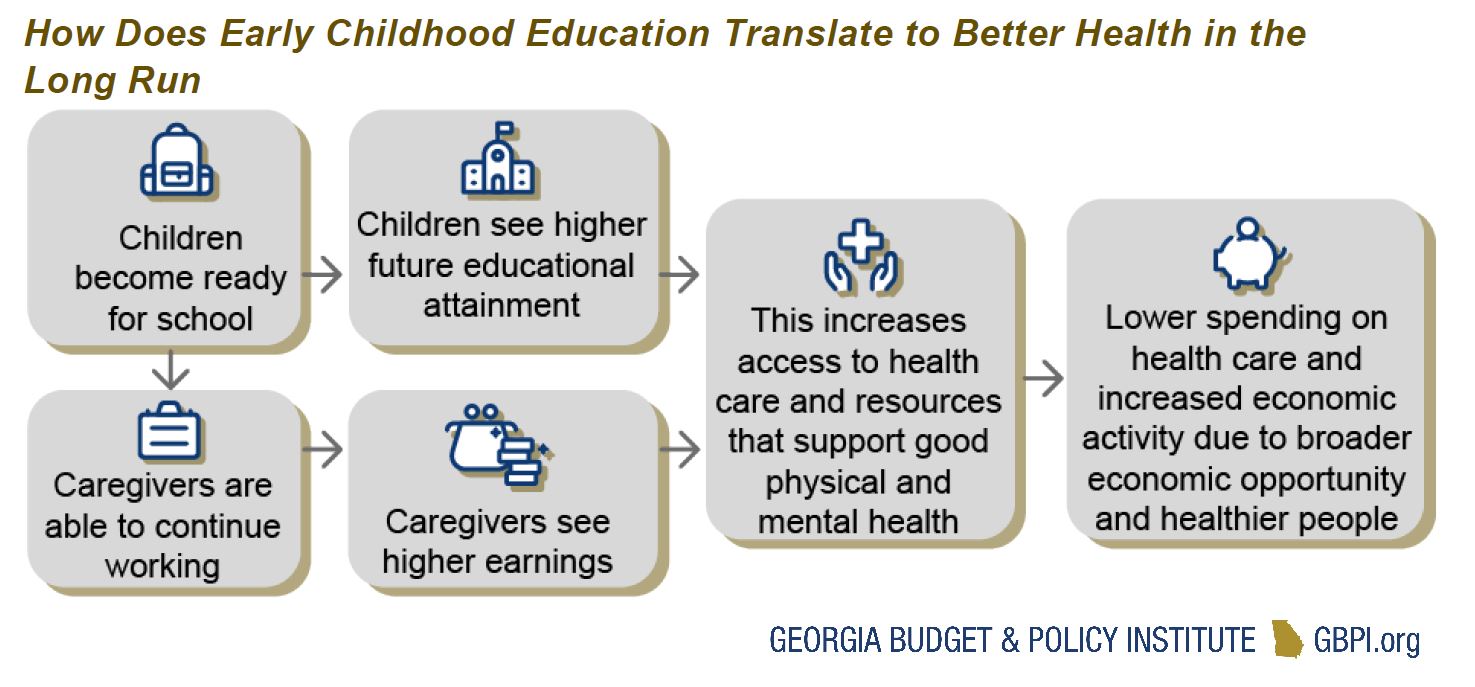

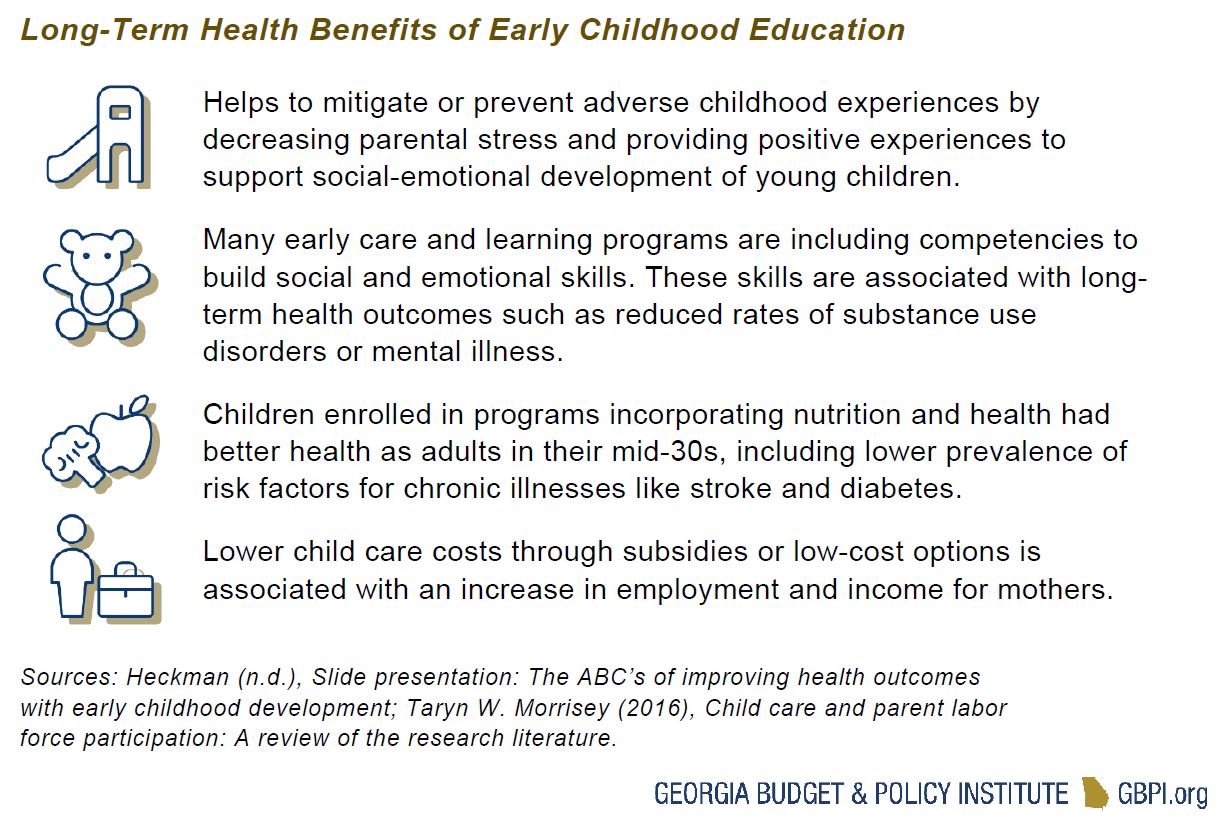

The Lasting Impact of Early Education on Health and Return on Investment

Early childhood education not only helps children and families with the resources to support their health and well-being today, but it can also help Georgia have a healthier population in the future and reduce long-term health care costs. The long-term benefits can be seen in the outcomes for children enrolled in the programs and their parents or caregivers, as well as in the cost-benefit of early childhood education.

Investing in early education programs and supporting these programs to include health components (e.g., screenings and nutrition) can help the state improve the health of children and their families and increase their earnings while producing a return on investment through savings in remedial education and health care costs. An analysis of over one hundred public assistance programs found that investing directly in health and education for children in households with low incomes has the best cost-benefit ratios.[15]

In addition to the return on investment, adequate early care and education can help avoid costs associated with failing to make these programs more accessible. Challenges with securing child care lead to about a $1.75 billion loss in annual economic activity due to employee absences and turnover and another $105 million in lost state tax revenue each year as parent income declines.[16]

Lastly, child care providers undergird the economy as a critical industry and support for working people. A 2016 economic report revealed Georgia’s early care and education industry generates $4.7 billion in economic activity each year and employs nearly 85,000 Georgians. Additionally, the level of parents’ annual earnings supported by the availability of child care in the state is $24 billion.[17]

Early Childhood Education as a Tool for Health Equity

Racism and poverty can create many disadvantages during early childhood that influence health and well-being throughout life. Structural racism, an enduring collection of discriminatory practices and racial biases across several facets of life such as health and education, limits the ability for parents to earn higher wages and build wealth, denies equitable access to healthy living conditions to families of color and leads to bias against children and parents of color—which results in chronic stress for Black and Brown parents at all income levels and higher rates of expulsion from preschool for Black children.[18]

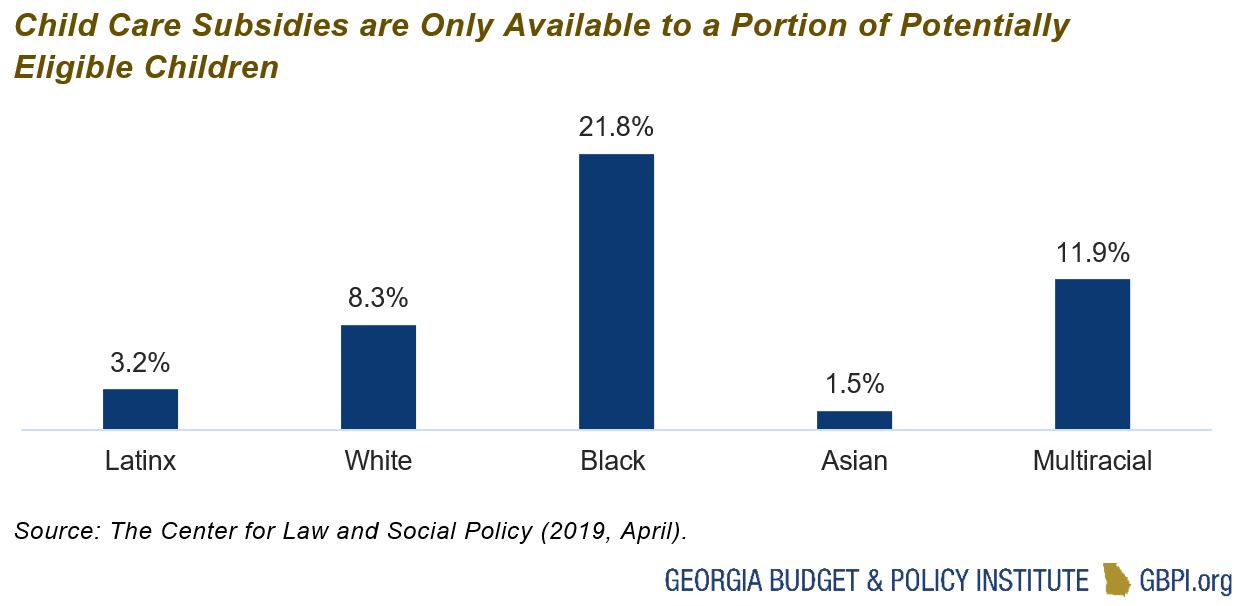

Black students in Georgia are 3.6 times more likely to be suspended than white students. Georgia passed legislation in 2018 that limits expulsions and suspensions of five days or more for public preschool to third grade by requiring the student to receive a multi-tiered system of supports first. But additional steps like using supports to prevent the need for suspension or expulsion and working to overcome racial bias during staff professional development can improve health equity by ensuring Black children receive the benefits of early education without disruptions.[19] Furthermore, increasing the equitable access to child care subsidies plays an important role in realizing the health benefits of early childhood education. While only 15 percent of Georgia children who could be eligible for child care subsidies, a far lower share of potentially eligible Latinx and Asian children receive child care subsidies.[20] Making early childhood education programs more accessible and affordable and removing barriers children of color face in early education settings can help reverse the effects of structural racism on the healthy development of children.

Maximizing the role of early education in promoting health equity also includes policy solutions to support the health of the early childhood education workforce. Child care workers in Georgia earn an annual average salary of $20,330, and 53 percent nationally are enrolled in public assistance programs, compared to 21 percent of the overall workforce. [21], [22] Over half of the lead teachers for infants/toddlers and 3-year-olds in child care learning centers are Black.[23] Many child care workers may not be able to afford health coverage and experience high levels of stress and depression, partly due to the low pay. In addition to working on increasing wages for these workers, the state can consider options like enacting a refundable earned income tax credit for low wage earners to keep more of their wages and expanding Medicaid, which could cover over 7,000 child care workers who are currently without health insurance coverage.[24]

Policy Solutions to Improve Health in Georgia through Early Childhood Education

Access to affordable, quality early childhood education was a challenge before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ongoing work to increase access to these programs will allow more children and families to realize the health benefits that come with participation in early childhood education programs. Now it is critical to support early education programs like child care centers to sustain them beyond the pandemic and to build on the state’s efforts to coordinate cross-sector collaboration between early childhood education and health through programs like Babies Can’t Wait. Some key recommendations at the intersection of early childhood education and health include:

Building on the recent boost in child care funding by expanding access to the CAPS program.

In 2018, DECAL received a historic funding boost of $93 million, which allowed the agency to make improvements like increasing reimbursement rates for infants and toddlers, hiring more support staff for children’s social and emotional health needs and supporting early learning workforce development.[25] State lawmakers can continue this progress by increasing the amount of child care subsidies available to low-income families through CAPS. The program is set to support about 50,000 children a year, but there are a total of 364,000 children who potentially need affordable child care due to lower family incomes.

Increasing coordination between state health agencies and DECAL and continuing investments in cross-sector initiatives.

Through programs like Babies Can’t Wait and home visiting, the Department of Public Health is able to coordinate services with early education programs to deliver evidence-based targeted early interventions. Georgia can build on this with other health agencies and health providers. The Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities does not currently include children younger than four in its System of Care State Plan. The agency is reviewing the plan and can consider extending the plan to include children under four.[26] The Department of Community Health, which runs the Medicaid program, can update their reimbursement policy to allow payment for services like social-emotional screenings for infants and toddlers and dyadic treatment—where a therapist treats the child and caregiver together.[27]

Federal lawmakers should include funding for child care programs as part of the COVID-19 relief efforts.

Child care programs require additional funding to remain in business after losing money due to closures and reduced enrollment and to provide care to essential workers. An allocation of $50 billion in federal funding for child care would help cover over five months of emergency care and relief. Using the same formula that determined funding distribution in the CARES Act, this would bring $2.1 billion to support Georgia’s child care programs.[28]

Thank you to Allison Setterlind, State Head Start Collaboration Director at the Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning, Wande Okuronen-Meadows at Little Ones Learning Center and Callan Wells, Hanah Goldberg and Jessica Woltjen at Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students (GEEARS) for your insights and resources that helped inform this report.

Endnotes

[1] Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (2020, August). 2021 Georgia Budget Primer. https://gbpi.org/georgiabudgetprimer/

[2] The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020, August). Child population by age group in Georgia. KIDS COUNT Data Center. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data#GA/2

[3] Quality Rated. (2020). https://families.decal.ga.gov/

[4] Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students. (2020, August). Simply not sustainable: Georgia parents’ experiences during the COVID-19 crisis. https://geears.org/wp-content/uploads/COVID19-Family-Experience-Survey.pdf

[5] Gould, E. & Shierholz, H. (2020). Not everybody can work from home: Black and Hispanic workers are much less likely to be able to telework. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/black-and-hispanic-workers-are-much-less-likely-to-be-able-to-work-from-home/

[6] National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2020, March 27). A state-by-state look at child care in crisis: Understanding early effects of the coronavirus pandemic. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/state_by_state_child_care_crisis_coronavirus_surveydata.pdf

[7] Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students. (2020, March 30). GEEARS Statement: Social Distancing Guidance Should Extend to Child Care Sector. https://geears.org/news/social-distancing-child-care-sector/

[8] Childcare Aware. (2019). Price of child care in Georgia. https://info.childcareaware.org/hubfs/2019%20Price%20of%20Care%20State%20Sheets/Georgia.pdf?utm_campaign=2019%20Cost%20of%20Care&utm_source=2019%20COC%20-%20GA

[9] Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning. (2019). CAPS Policy – Priority Groups.

[10] The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2017). New report shows racial barriers prevent children of color and immigrant children from reaching potential, post recession. https://www.aecf.org/blog/new-report-shows-racial-barriers-prevent-children-of-color-and-immigrant-ch/

[11] Lee, J. (2020, June 17). Keeping pre-K stable helps Georgia children and parents. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/keeping-pre-k-stable-helps-georgia-children-and-parents/

[12] Georgia’s Cross Agency Child Data System. (2019). www.gacacds.com

[13] Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning, Bright from the Start. (2020). 2019 annual report. https://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/BFTSAnnualReport2019.pdf

[14] Camardelle, A. (2019, June 27). Georgia’s boost in child care funding. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgias-boost-in-child-care-funding/

[15] Hendren, N., & Sprung-Keyser, B. (2020). A unified welfare analysis of government policies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(3), 1209–1318. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa006

[16] Goldberg, H., Cairl, T., & Cunningham, T. J. (2018). Opportunities Lost: How Child Care Challenges Affect Georgia’s Workforce and Economy. Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students. http://geears.org/wp-content/uploads/Opportunities-Lost-Report-FINAL.pdf

[17] Bright from the Start: Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning. (2016, June). Economic Impact of the Early Care and Education Industry in Georgia. http://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/EconImpactReport.pdf

[18] Braveman, P., Acker, J., Arkin, E., Bussel, J., Wehr, K., & Proctor, D. (2018, May). Early Childhood Is Critical to Health Equity. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2018/05/early-childhood-is-critical-to-health-equity.html

[19] National Black Child Development Institute. (2019). State of the Black child report card: Georgia. https://www.nbcdi.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/NBCDI%20SOBC%20Report%20Card%20Georgia.pdf

[20] Ullrich, R., Schmit, S., & Cosse, R. (2019, April). Inequitable access to child care subsidies. The Center for Law and Public Policy. https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2019/04/2019_inequitableaccess.pdf

[21] Bright from the Start: Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning. (2016, June). Economic impact of the early care and education industry in Georgia. http://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/EconImpactReport.pdf

[22] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Committee on Applying Neurobiological and Socio-Behavioral Sciences from Prenatal Through Early Childhood Development: A Health Equity Approach. (2019). Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. Negussie, Y., Geller, A., & DeVoe, J. E. (Eds.). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551492/

[23] Bright from the Start: Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning. (2016, June). Economic impact of the early care and education industry in Georgia. http://www.decal.ga.gov/documents/attachments/EconImpactReport.pdf

[24] Sweeney, T. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute & Georgians for a Healthy Future. (2015, September 23). Understanding Medicaid in Georgia and the opportunity to improve it. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute & Georgians for a Healthy Future. https://gbpi.org/understanding-medicaid-in-georgia-and-the-opportunity-to-improve-it/

[25] Camardelle, A. (2019, June 27). Georgia’s boost in child care funding. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgias-boost-in-child-care-funding/

[26] Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students & National Center for Children in Poverty. (2019, September). What Policymakers in Georgia need to know about infant-toddler social-emotional health. http://geears.org/wp-content/uploads/IECMH-Brief-for-Policymakers-FINAL.pdf

[27] Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students & National Center for Children in Poverty. (2019, September). What Policymakers in Georgia need to know about infant-toddler social-emotional health. http://geears.org/wp-content/uploads/IECMH-Brief-for-Policymakers-FINAL.pdf

[28] Schmit, S. (2020, May). Why we need $50 billion in pandemic child care relief: A state-by-state estimate. The Center for Law and Social Policy. https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020/05/2020_50billionpandemicchildcare_0.pdf