Key Points:

- The current COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic decline have underscored the problems of disinvestment in Georgia’s safety net programs, such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or food assistance), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, or cash assistance), Medicaid and other programs.

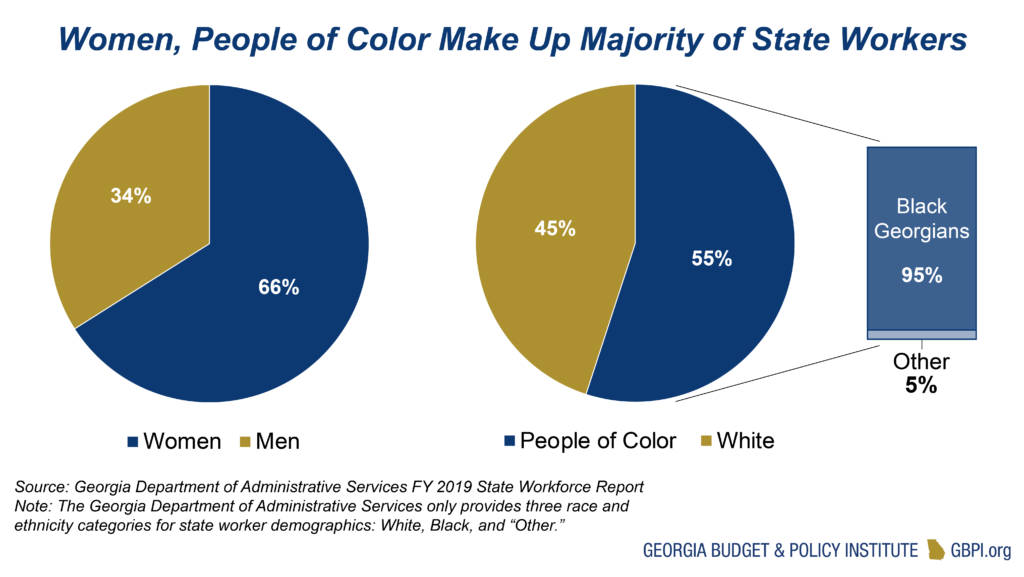

- The state has recently called for steep budget cuts, which are resulting in layoffs, furloughs and hiring freezes. State workers, who are predominantly women and people of color, are already underpaid and facing increasingly demanding workloads. These cuts will exacerbate those problems, while creating deeper inequities in our state.

The current pandemic has led to an alarming 2 million Georgians laid off in a matter of months. As history shows us, these difficult shocks to the state economy increase poverty and the demand for services that help people meet their needs, such as food or money to pay rent or a mortgage. State investments in safety net programs, especially food assistance and direct cash assistance for families with little or no income, need to be protected at all cost. A rapid decline in revenue resulting from the pandemic should serve as a warning signal that Georgia lawmakers must prepare to address rising poverty and inequities that will worsen during this time. Instead, with a call to slash state spending across the board, state leaders are pursuing the opposite.

The last thing that millions of Georgians who have lost income over the last two months need to hear is that lawmakers will approve a state budget that cuts funding for programs meant to help them meet their basic needs. Safety net services are administered by the Department of Human Services. State workers in these departments help eligible Georgia families enroll in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or food assistance), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, or cash assistance), Medicaid and other programs.

State workers have seen their caseloads climb exponentially since the start of the public health emergency. Unfortunately, the state spending that helps pay the salaries of the caseworkers responsible for connecting Georgians with low incomes with support is on the chopping block. The FY 2021 budget proposal for DHS would cut a combination of state and federal spending in these categories by $37 million, leading to mass furloughs and the loss of valuable frontline positions. The cuts will fall more sharply on residents and state workers who are women and Black, as earlier recessions have shown. Weakening this critical and already-thin state infrastructure will hinder recovery for people with low incomes hit the hardest by COVID-19 who need to seek help from the safety net.

The cuts not only hurt those who receive state services or participate in the programs, they also have an impact on the workers themselves who are disproportionately women and people of color. Sadly, those workers are overrepresented in the lower rungs of the state’s workforce, and in some cases turn to the state’s safety net themselves when taking a pay cut or are furloughed or laid off. The state’s cuts compound stubborn low wages for state workers. For example, the salary for an Economic Support Supervisor at DHS ranges from $36,000 to $39,000 annually – near the poverty line for a family of three. Choosing to pay these workers any less than the poverty wages they already make during the downturn is a direct and unjust contributor to Georgia’s long-standing racial and gender inequities.

The news of cuts likely adds fatigue to state workers who were already dealing with four and six percent cuts ordered by the Governor prior to the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on the state budget. In those early hearings in the 2020 legislative session where agency heads and members of the public described the cuts, it was clear that they were already working with far too few resources to get their jobs done. During the DHS budget hearings, the agency’s leadership revealed that caseloads for SNAP and other public assistance programs were already backlogged, with workers expected to process far more than they could handle despite “historically low” unemployment rates in Georgia. Fast forward to today, the state has processed more applications in the last month than it did in the entire previous year, a spike in demand that puts more pressure on the state to fight rising poverty.

The DHS budget is a patchwork of state and federal funds. It is common to see budget writers move funds from one program to another which shields some programs from deep cuts while leaving others completely exposed. That is the case with this current budget proposal. Unlike other areas in the department’s budget, safety net services would not get help from other areas in the budget to make up for a funding loss. In fact, $46 million that could be used to boost economic assistance for families in need has been appropriated to reduce cuts in other areas in the agency’s budget.

The vulnerabilities in Georgia’s safety net system that we are experiencing were not recently discovered because of the pandemic. They were the result of a compilation of policy choices that were driven by a relentless attempt to “end welfare as we know it,” which unfortunately keeps millions of Georgians near the bottom of the economic ladder. Moreover, racist attitudes (both implicit and explicit) on both sides of the aisle have permeated the way Georgia lawmakers invest in the safety net. These attitudes and policies have led to harsh rules and disinvestment that have particularly impacted Black families. States that have larger Black populations are notorious for offering less help from the safety net. For example, Georgia’s cash assistance program only reaches 5 out of every 100 families in poverty today.

One of the chief roadblocks to achieving prosperity and racial equity in Georgia is long-term state disinvestment in the safety net. Evidence shows that states relying on spending cuts will make people worse off financially than those states that counter recessions by raising revenue. Cuts to safety net spending in particular increases income inequality. Those cuts fall disproportionately on the backs of women and Black and Latinx Georgians who are more likely to experience permanent economic insecurity as a result of economic downturns. Cutting state spending in the safety net will undoubtedly explode economic struggle for these Georgians.

In Georgia, when we are faced with a fiscal crisis, lawmakers historically attempt to balance the budget with cuts. But cutting programs and services at a time when an unprecedented number of Georgia families need support is the opposite of what is needed right now. Disinvestment has only exacerbated inequities before and during COVID-19. As we have said many times and will continue to do so at GBPI, “we cannot cut our way to prosperity.” Several options are on hand to reduce the revenue shortfalls and mitigate cuts to critical programs. These can be found in my colleague’s recent report laying out a menu of revenue options. If approved without raising new revenue, the proposed cuts to Georgia’s safety net budget will do nothing short of reinforcing racial and gender disparities in poverty rates, household income, housing and food insecurity, and health outcomes.