Nearly two years into a global public health crisis, most people are experiencing some degree of pandemic burnout, but COVID-19 and its ensuing economic effects have not impacted everyone equally. People who were systematically marginalized before the pandemic are bearing the brunt of its devastation, especially women of color with low incomes. Although Black women and Latinas are often the economic engines of their families and communities, their health, safety, financial and overall wellbeing are constantly deprioritized. Only by leveraging the economic power of Georgia’s women of color can we create a truly prosperous state.

Prior to the pandemic, Black women and Latinas faced substantial barriers to economic success and disparities in jobs and wages. Black women and Latinas in Georgia are about two times more likely to live in poverty than white women. According to 2019 data, 16 percent of working-age Georgia women live in poverty compared to 14 percent in 2017.[1] Black and Latina working-age women in Georgia are the most impacted, where more than 1 in 5 (21 percent) live in poverty.[2] Additionally, women in Georgia are paid just 80 cents for every dollar paid to men, and Black and Latina full-time working women are typically paid just 63 cents and 55 cents respectively for every dollar paid to men. This is critical because most Georgia families with children rely on mothers’ earnings. Nearly two-thirds of mothers are the primary or co-breadwinners (head of household or earning at least 25 percent of household income) in Georgia households, and nearly 80 percent of Black mothers are primary breadwinners (head of household or earning at least 40 percent of household income) for Georgia families.

A legacy of racist policies and discriminatory practices combined with systems of patriarchy and white supremacy have contributed to an economy that limits economic opportunity for Black women and Latinas in Georgia. Their work is often undervalued and underpaid, their role as mothers and caregivers is treated as invisible, and the existing care infrastructure and safety net are insufficient to support their needs—particularly for single women with children. For example, under the 1935 Social Security Act, unemployment insurance and retirement insurance programs explicitly excluded agricultural and domestic workers, sectors where most Black women worked, and Black women were excluded from better-paying, higher-status jobs until the 1970s. Today, Black women and Latinas are continually subjected to occupational segregation and overrepresented in jobs that pay low wages and that do not offer upward mobility or stability. For example, as of 2018, Black & Latina women of working age make up 51 percent and 26 percent of maids and house cleaners, respectively, but only 12 percent and 3 percent of the total Georgia population.[3] And this job pays a median weekly wage of $457 per week and is unlikely to offer health insurance or other benefits. Overall, the job market and employers are failing to support a livable wage for women of color.

These policies and systems have left Black women and Latinas with limited economic opportunities and financial reserves to weather economic hardship. With a median wealth of just $200 and $100 respectively, Black women and Latinas have few resources to draw on when impacted by job losses, which they suffered disproportionately throughout the pandemic. They were more likely to work in industries that were hit hard by layoffs including hospitality, retail and restaurants. They also faced a greater risk of exposure to COVID-19 as they were overrepresented in jobs deemed essential providing child care, grocery and convenience services and building cleaning services.

Throughout the pandemic, recovery has been slowest for Black and Latina workers. Black workers remain consistently underrepresented among unemployment insurance (UI) claims, due in part to being paid lower wages or having unstable jobs that don’t meet UI eligibility thresholds. Although Black women have remained active job searchers in Georgia over the past 18 months,[4] they are often subjected to jobs in industries with the highest risk of job loss and face ongoing racial discrimination and bias in the workplace, which together may keep them out of jobs longer and make it harder to land a quality job. Their high levels of underemployment (11.9 percent in the third quarter of this year, the highest of any other group[5]) demonstrate another trend that is likely happening to Black women, where their unemployment levels have dropped over the course of the pandemic recovery but they have not landed quality or full-time employment and have resorted to part-time work to try to make ends meet and/or accommodate child care challenges.

Hispanic women in Georgia have experienced the greatest swings in unemployment from the pandemic’s start through the ongoing recovery, ending in very low unemployment rates for Hispanic women in Quarter Three (Q3) 2021 (0.7 percent). They are the only demographic of women that experienced explosive growth in their labor market participation (+20.9 percent by Q3 2021) concurrently with high underemployment in (10.3 percent in Q3 2021). This suggests that while they experienced some of the harshest unemployment earlier in the pandemic (19 percent in Q2 2020), their lack of access to other public supports—such as very low UI enrollment levels—have pushed them back into the workforce faster than other groups, but into jobs that offer reduced or part-time pay.[6]

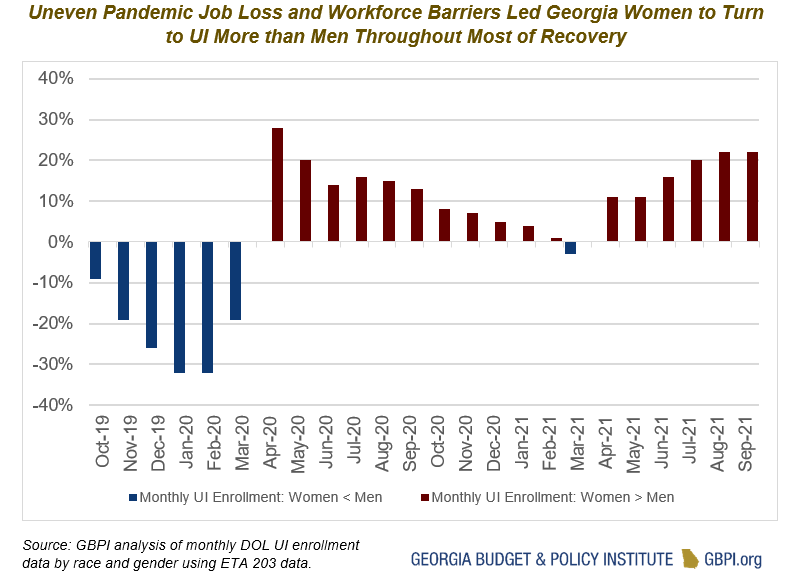

Despite these disparities, Georgia’s leaders chose to end the state’s participation in the extended federal UI benefits in June 2021. This included ending the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) benefits that expanded access to self-employed, gig and part-time workers unable to work as a result of COVID-19. Given that many Black women and Latinas are underemployed and working in these types of positions, ending these benefits may have impacted them disproportionately. Also, UI enrollment trends among women versus men in the pandemic recovery show that when the federal pandemic UI programs left Georgia, disparities in UI enrollment climbed to their highest levels since the start of the pandemic.

In addition to unemployment insurance, other public benefits and supports are necessary to help families make ends meet during times of financial hardship. Georgia has one of the lowest Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) monthly benefit amounts in the country—$280 for a family of three. And TANF, or cash assistance, doesn’t reach many of Georgia’s families living in poverty. In fact, for every 100 families in poverty in Georgia, only five receive the benefit. Georgia’s low TANF benefits and limited reach are a racial justice issue given that Black TANF recipients are the largest racial/ethnic group on the program in Georgia. Further, policies like work requirements and family caps in Georgia were justified through racist narratives of Black women.

Presenting another obstacle is the lack of child care infrastructure in Georgia that has been strained further during the pandemic. Our lack of investment in care infrastructure is rooted in a legacy of slavery and unpaid labor. Historically, Black women were forced to care for the children of their enslavers and then, when slavery was abolished, they were relegated to care and domestic work. Today, Black women and Latinas remain overrepresented in the child care workforce. For example, 1 in 5 child care workers is Latina (20 percent) or Black (19 percent) though they make up just under 8 percent and 7 percent of the overall workforce respectively.

Child care challenges disrupt workforce participation, especially for single mothers, and have major impacts on the state’s economy. In fact, Georgia’s lack of child care infrastructure leads to at least $1.75 billion in economic activity losses and an additional $105 million in annual tax revenue losses. And the high cost of child care hinders women’s labor force participation. The average cost for full-time weekday center-based child care in the Atlanta metro area for children ages 0 to 5 is $179.75 per child per week—more than $9,300 per year, a hefty sum many families cannot afford. While the average number of staff at child care centers is rising, it has not returned to pre-pandemic levels, and national stories report that insufficient wages have contributed to the exodus of child care workers. Without affordable child care options, many women have to work part-time or drop out of the workforce to care for their children.

Conclusion

Our policymakers must consider the holistic needs of Georgia’s women as workers, mothers, caregivers and breadwinners. GBPI has been striving to advance an economic policy agenda with an intersectional lens on race and gender. While we focus largely on state policies, when we see state leaders not stepping up—as has been the case too often during the pandemic—we look to federal lawmakers to enact equitable policies. The American Rescue Plan Act sent $4.7 billion in flexible funding to Georgia, money that is still unaccounted for. The state must put those dollars towards equitable investments—e.g., restoring budget cuts to ensure money flows to communities of color, direct payments made through a state Earned Income Tax Credit or an Opportunity Weight to ensure equitable education funding—that target those most impacted by the pandemic, particularly Black and Latina women. Those federal investments and existing state funding and revenue sources can be leveraged to foster greater economic equity across Georgia’s households. Additionally, Congress’s new Build Back Better recovery plan includes opportunities for an equitable recovery, but more must be done to support paid leave and child care and to modernize and expand UI accessibility so that underpaid Georgia workers, who are disproportionately Black women and Latinas, can supplement lost wages while seeking work after an involuntary job loss.

Finally, public policy and systems change must include narrative and cultural changes as well. Black and Latina women’s labor is often undervalued and invisibilized yet we rely on them to play critical roles in Georgia’s families, workforce and communities. We must uplift the full humanity of Black and Latina women, end dehumanizing stereotypes and tropes (e.g., “welfare queen”), and address occupational segregation as well as gender and racial pay and wealth gaps. Centering Black and Latina women in our economic policy decisions is the only way to create a truly equitable Georgia where everyone can prosper.

Endnotes

[1] GBPI analysis of Census American Community Survey data; numbers based on 2019 5-year estimates.

[2] Ibid.

[3] GBPI analysis of US Census 2018 Population Estimate.

[4] GBPI analysis of Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata from Q1 2020 to Q3 2021.

[5] Ibid. GBPI’s unemployment and underemployment rate analysis is based on IPUMS Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata, which produces slightly different numbers for some months than state employment statistics published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) that also incorporate other sources; however, the CPS microdata are the only timely and publicly-available source for disaggregated state-level employment data.

[6] Ibid.