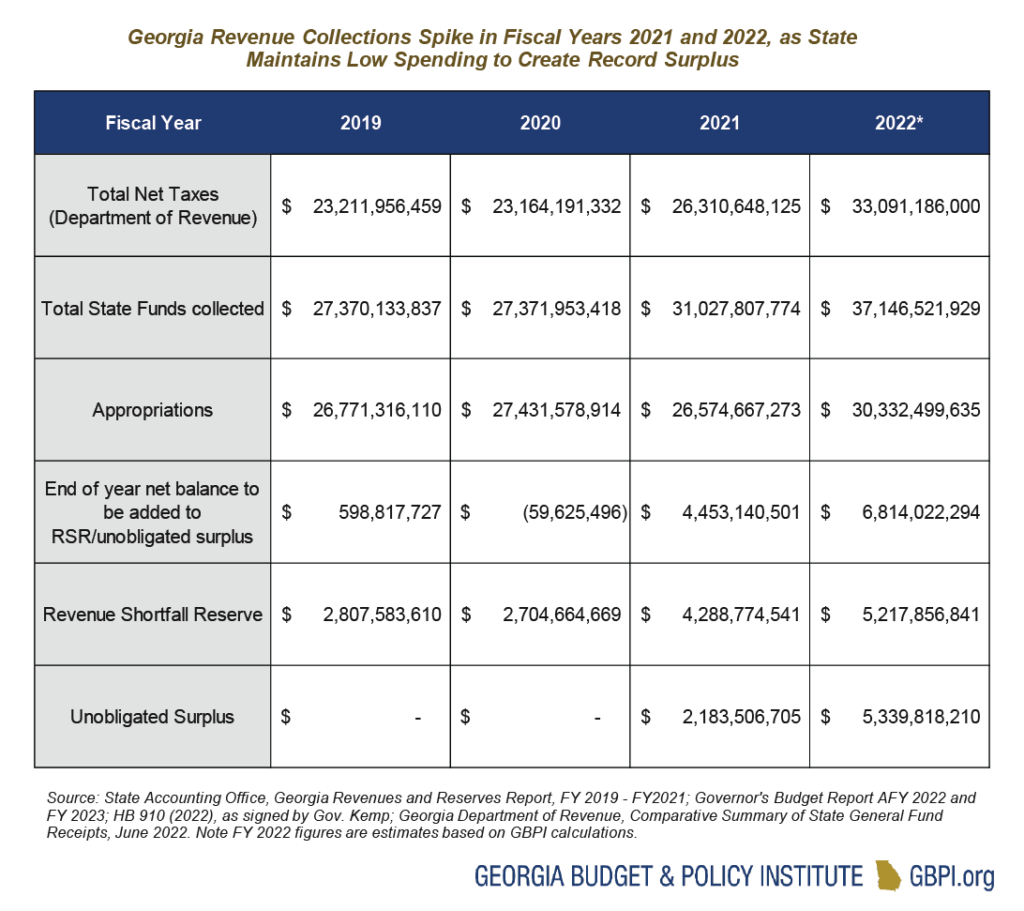

Last month, Georgia’s Department of Revenue released its report of unaudited tax collections for Fiscal Year (FY) 2022, which ended on June 30, indicating that the state will once again run a surplus that leaves it with a record level of cash on hand and a full Revenue Shortfall Reserve (RSR) that acts as the state’s savings account. In September, Georgia’s state accounting office will release a more fulsome report that details all revenue collections and state spending in addition to the balance of its reserve accounts.

Where do surplus revenues go?

The RSR was created in 1976 to help manage instability in revenue collections and hedge against the possibility of a recession. When the state raises more in revenue than it spends, it produces a surplus. At the end of each fiscal year, any surplus in general revenue collections is automatically added to the state’s RSR, until that account reaches 15 percent of prior year collections. At that point, funds go into a separate account that represents unobligated or undesignated surplus. This is in addition to a dedicated reserve account for surplus funds raised by the Georgia Lottery, as well as smaller reserve accounts used to help manage bond payments and tobacco settlement funds.

Beyond the availability of surplus funds, which could be added to the governor’s revenue estimate to be appropriated by the General Assembly, the state is also experiencing a widening gap between its official revenue estimate and the amount of revenue it appears likely to collect in FY 2023. Georgia’s official revenue estimate is the cornerstone of the executive budget power held by the state’s governor to shape the state’s spending plan. Setting the revenue estimate is a policy decision, made in consultation with the state economist, that caps the amount of funding available for appropriation, which is the corresponding constitutional responsibility of the General Assembly.

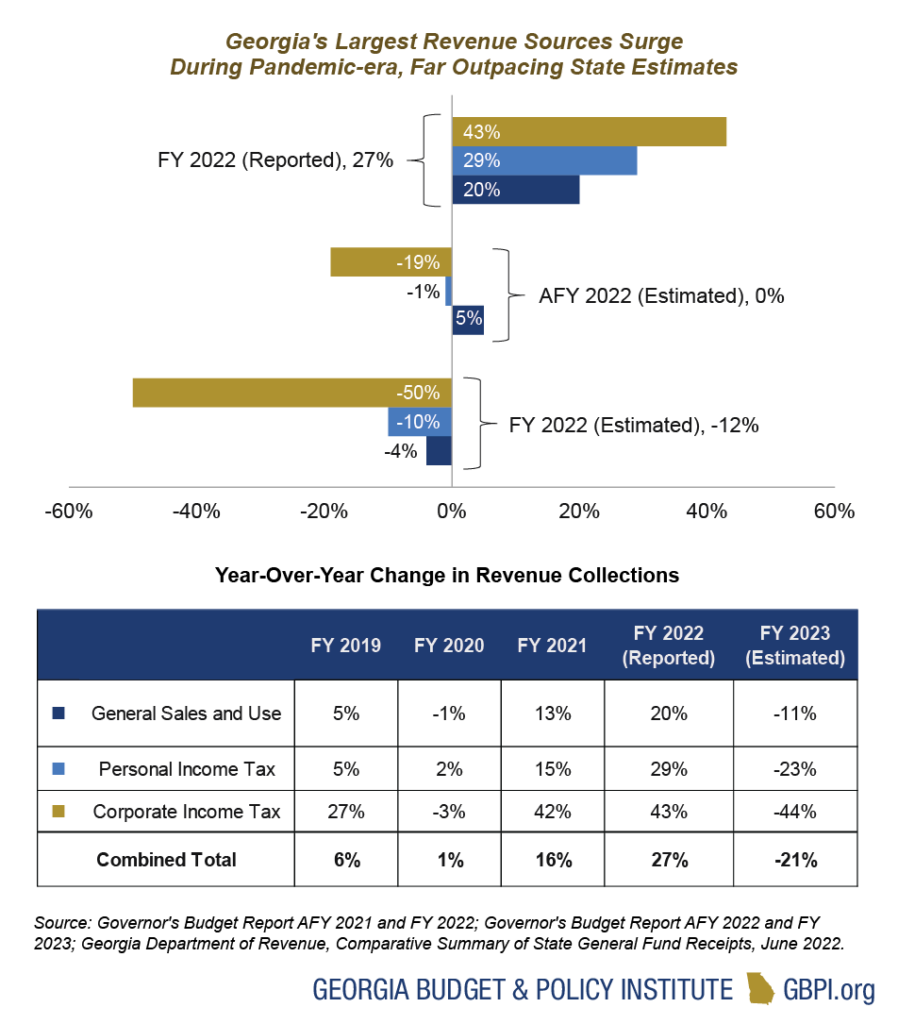

As it currently stands, the state estimates that it will collect 21 percent less in income and sales and use taxes in the current fiscal year (FY 2023) than it reported for the previous year, which comprise approximately two-thirds of the entire state budget. Even after accounting for a potential economic recession and the effects of tapering federal spending, it appears that consecutive years of conservative revenue estimates have compounded such that Georgia could raise significantly more than it currently plans to spend in the upcoming year.

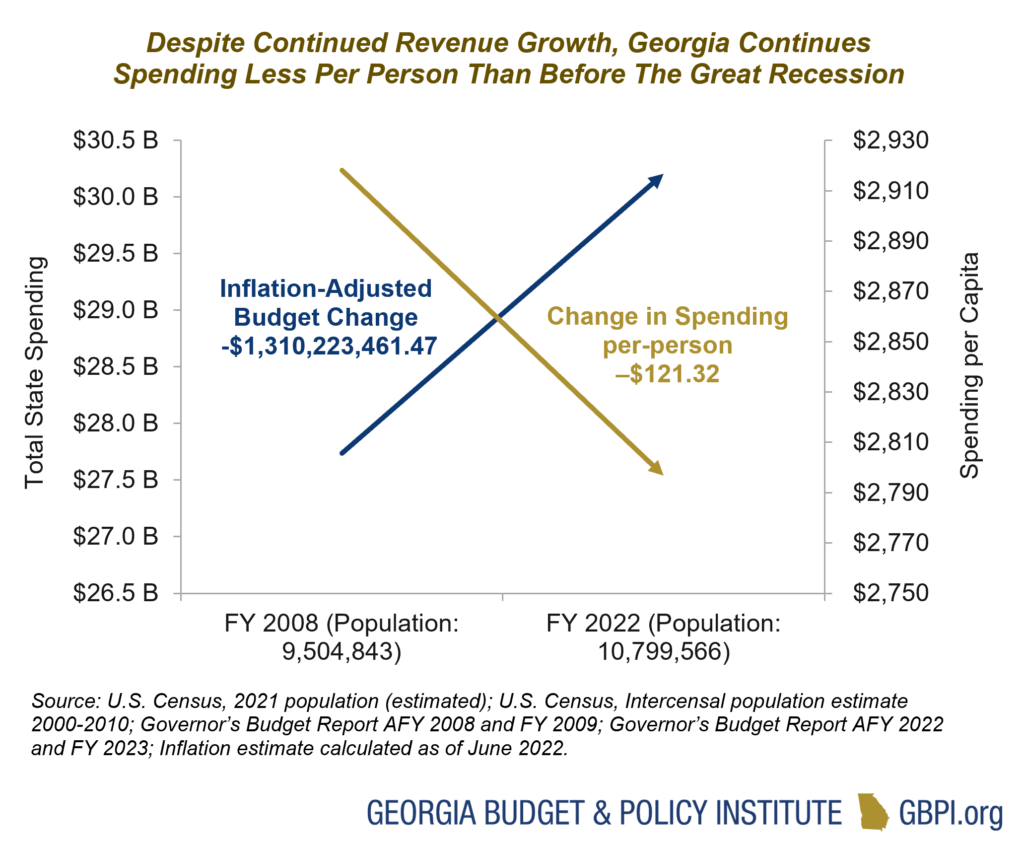

Furthermore, in FY 2023, the state plans to spend approximately $121 less per resident—an aggregate of $1.3 billion less—than it did before the Great Recession, when Georgia’s budget was upended by spending cuts the state made in response to weakened revenue collections.

Now, with a full Revenue Shortfall Reserve that is likely to exceed $5 billion and an estimated unobligated surplus that also appears set to total more than $5 billion—state leaders have a unique opportunity to make long-deferred investments and make up ground lost to over a decade of austerity. This means that even if state revenue collections come in below the revenue estimate set by the governor, Georgia’s existing reserves are almost certain to be more than sufficient to cover the difference. This is important to note because of the range of options presented to state leaders by the unprecedented level of resources available, whereby surplus funds could either be preemptively added to the governor’s revenue estimate or could provide a backstop to guard against economic uncertainty. This healthy fiscal position provides an opportunity to appropriately right-size Georgia’s revenue estimate to reflect collections more accurately going forward.

State Has Prioritized Growing Surplus Accounts Over Funding for Programs, Services and Workforce

Due to the state’s response to the Great Recession, the balance of Georgia’s Revenue Shortfall Reserve fell from $1.5 billion in FY 2007 to just over $100 million in FY 2009.[1] Following a sharp decrease in state revenue collections, then-Governor Deal made it a key priority to rebuild the state’s reserve account by setting conservative revenue estimates to add to the balance of the RSR. During the eight years from 2010 to 2018, Georgia’s revenue collections averaged $305 million above the amount spent by state government annually.[2] As a result, the balance of the state’s savings account grew from $116 million in FY 2010 to over $2.5 billion by the time Deal left office.[3] However, as the state’s RSR has reached the maximum level of 15 percent allowed under state law, a trend of conservative revenue estimates issued by Gov. Kemp since FY 2019 has helped to create the state’s current fiscal position, in which it maintains a relatively low level of spending but continues to add to increasingly flush reserve accounts.

Additionally, in response to the 2020 pandemic-induced recession, state leaders again made across-the-board spending cuts as Georgia’s primary response to an expected decline in revenue collections.[4] Also, in contrast to the previous recession, outside of a limited release at the onset of the pandemic, Gov. Kemp declined to add funds from RSR to help manage through the downturn, instead relying primarily on spending cuts. However, due in large part to an unprecedented federal intervention, the state registered only a modest decline in revenue collections, which was followed by a surge in both FY 2021 and 2022. As a result of this combination, Georgia preemptively made deep budget cuts of 10 percent to most state agencies and programs, cuts that were unnecessary to withstand the negative economic effects of the pandemic.

In parallel, Georgia’s system-wide workforce was cut from approximately 101,000 state employees in FY 2008 to 81,000 in FY 2018 to less than 76,000 by FY 2021.[5] Looking at only full-time employees, the state’s workforce dropped from 83,000 to 60,000 between FY 2008 and 2021, a decline of nearly 28 percent. In recent years, this trend has only accelerated. In fact, among executive branch agencies, the reported 8.7 percent decrease in full-time state employees from 2019-2021 represents the sharpest decrease since 2008-2010.[6] Furthermore, as of FY 2021, the state registered an all-time-high employee turnover rate of 23 percent due in part to a failure to adequately raise salaries in line with market conditions.[7] While a host of factors combine to influence the state’s revenue estimate and actual revenue collections, these trends and policy decisions have helped to create the record gap observed in FY 2022.

Conclusion

As state leaders look ahead, the 2023 legislative session stands to be a pivotal inflection point for the state budget, which affects all 10.8 million Georgians. Public education and health care comprise approximately 73 percent of the entire state budget, while those categories and infrastructure, corrections, human services and public safety combined constitute approximately 95 percent.[8] To make the highest and best use of the taxes and revenues collected from Georgians, the state would be best served by right-sizing its revenue estimate to more accurately predict actual collections and allow for greater resources to be directed to urgent needs.

In areas across the state budget, the consequences of prolonged austerity remain clear, as Georgia ranks among the bottom 10 states nationally in state expenditures per person.[9] Georgia has fallen behind in K-12 education as one of six states that does not provide funding for schools to educate students living in poverty.[10] Furthermore, the state also maintains the third highest uninsured rate in the United States, as communities across the state continue to reel from the effects of the pandemic and brace for a wave of likely rural hospital closures as recent boosts to federal funding taper off.[11] With unprecedented resources on hand in reserves to provide added security in appropriately funding the needs of Georgians, state leaders must take advantage of this unique opportunity to make long-overdue adjustments and ensure all Georgia families can thrive.

Endnotes

[1] Governor’s Budget Report Amended FY 2022 and FY 2023.

[2] GBPI calculations of nominal surplus, see Governor’s Budget Report Amended FY 2022 and FY 2023.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Kanso, D. (2022, January 21). Overview of Georgia’s 2023 Fiscal Year Budget. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/overview-of-georgias-2023-fiscal-year-budget/

[5] Human Resources Administrative Division. (2021, November). Department of Administrative Services. State of Georgia TeamWorks HCM System Fiscal Year End 2021 workforce report (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021). https://doas.ga.gov/assets/Human%20Resources%20Administration/Workforce%20Reports/Fiscal%20Year%20End%202021%20Workforce%20Report.pdf

Note: System-wide headcount includes employees of the executive branch, judicial branch, legislative branch, and local/affiliate government agencies. Not included are K-12 educators or employees of the University System of Georgia.

[6] Human Resources Administrative Division. (2021, November). Department of Administrative Services. State of Georgia TeamWorks HCM System Fiscal Year End 2021 workforce report (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021), page 2. https://doas.ga.gov/assets/Human%20Resources%20Administration/Workforce%20Reports/Fiscal%20Year%20End%202021%20Workforce%20Report.pdf

[7] Human Resources Administrative Division. (2021, November). Department of Administrative Services. State of Georgia TeamWorks HCM System Fiscal Year End 2021 workforce report (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021), page 9.https://doas.ga.gov/assets/Human%20Resources%20Administration/Workforce%20Reports/Fiscal%20Year%20End%202021%20Workforce%20Report.pdf

[8] Kanso, D. (2022, January 21). Overview of Georgia’s 2023 Fiscal Year Budget. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/overview-of-georgias-2023-fiscal-year-budget/

[9] Fiscal Research Center. (2022, January). Georgia’s rankings among the states: Budget, taxes, and other indicators. https://frc.gsu.edu/files/2022/01/ga-rankings-among-the-states-budget-taxes-and-other-indicators-spread-2022.pdf

[10] Owens, S. (2022, February 1). Opinion: Georgia students living in poverty left behind in Kemp’s plan. Atlanta-Journal Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/education/get-schooled-blog/opinion-georgia-students-living-in-poverty-left-behind-in-kemps-plan/4DLUXUY36FGYPGKYHTNSWFH73I/

[11] Dreher, A. (2022, July 14). Rural hospitals again face financial jeopardy. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2022/07/14/rural-hospitals-face-financial-jeopardy; Kaiser Family Foundation. “Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population.” https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Uninsured%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D