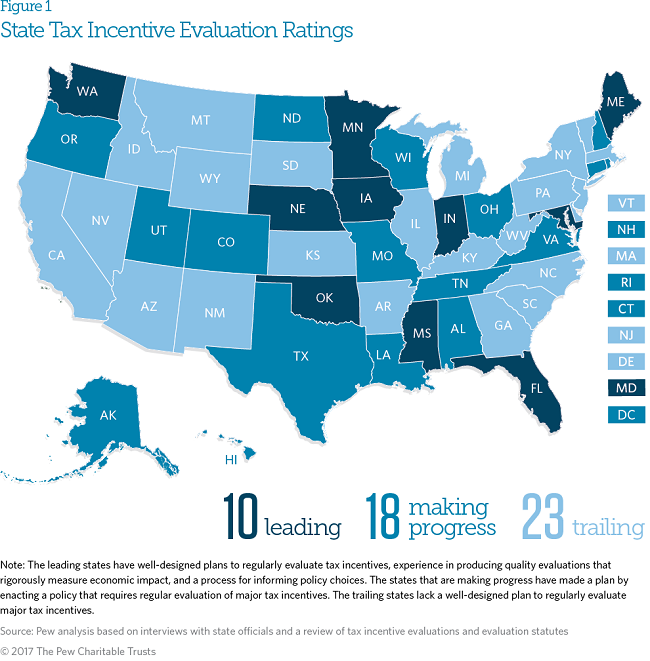

Georgia is falling behind the majority of states including several of its Southeast neighbors when it comes to making sure tax breaks deliver taxpayers a good return on investment. Twenty-seven states plus the District of Columbia now maintain policies that subject business tax breaks and other economic development subsidies to some sort of objective review and evaluation process, as detailed in a new 50-state study from the Pew Charitable Trusts. Georgia isn’t one of them, which the 2017 legislative session brought into stark relief.

State legislators and Gov. Nathan Deal approved at least 10 tax break bills with a hefty total price, in some cases based on scant evidence and after minimal debate. Georgia can do better in the future by following the lead of states like Florida and Mississippi that have emerged as leaders in making sure tax breaks are worth the cost.

Doling out tax breaks for favored interests is an annual ritual under Georgia’s Gold Dome, typically with little rhyme or reason as to which causes win out and which do not. This year legislators advanced new incentives for concrete-mixing companies, yacht owners, the film and music industries, and a dubious scheme to benefit out-of-state financial firms. Last year it was rural hospitals, big economic development projects and people who buy Super Bowl tickets. The year before the favored ones included real estate developers, venture capital investors and Mercedes-Benz employees. What common policy goals or governing philosophy bind these measures together? Your guess is as good as mine.

The costs of new business tax breaks can add up quickly, which poses a problem for lawmakers looking to adequately fund schools, roads and other vital services. The 10 measures approved by legislators this year and signed by the governor total nearly half a billion dollars in lost state revenue over five years, up only slightly higher from the norm of recent years. This is detailed in our April 2017 Adding Up the Fiscal Notes report, which examines each of this session’s tax measures.

Supporters of business tax breaks argue the costs are worth it, since new incentives are intended to generate productive activities such as new job creation or private investment. That’s likely true in a few cases, but untrue in many others. The problem is lawmakers can’t easily tell which is which because the state lacks any formal evaluation procedure to explore the costs and benefits of tax break programs and weigh whether, once granted, they achieve their goals at a reasonable cost.

A growing chorus of states is realizing that there’s a better way. As noted in the Pew study, 27 states plus the District of Columbia made progress in the past five years to measure if tax breaks are working as intended. In addition to Florida and Mississippi, other regional neighbors including Alabama, Tennessee and Texas are moving forward too. Here’s how Republican Gov. Mary Fallin of Oklahoma describes the impetus for change: “The state should keep incentives that work and phase out those that don’t. The problem is we do not have an effective and objective way of evaluating these incentives.”

Creating a better approach to tax breaks involves three core steps, according to Pew. States need a realistic plan to study tax break programs on a regular basis; they must review them rigorously and objectively rather than in a superficial or politically-charged way; and they should ensure evaluation results help shape actual policy choices instead of reports just sitting on shelves. Georgia can look to a pair of regional neighbors to see what this looks like in practice.

Florida enacted a new system in 2013 to require business tax breaks and some other economic development programs undergo review once every three years. Two nonpartisan legislative offices staffed by professional researchers collect data and use sophisticated economic modeling to gauge how a programs’ performance in the field compares to the cost in lost revenue. When programs aren’t working as legislators intend, the offices can offer recommendations for change. This worked as designed in 2015, when Florida lawmakers let a large subsidy program expire after evaluators determined it was simply shifting investment from place to place within the state, rather than attracting jobs from elsewhere.

Mississippi emerged as a leader in tax break accountability in 2014 with legislation that requires a respected research office in the state’s university system to look at economic development incentives every four years. The state’s first evaluation examined a program that committed more than $200 million in incentives for retail destinations such as outlet malls. Researchers unearthed some possible flaws in the initiative and offered recommendations for how lawmakers might improve it, such as requiring agencies to collect more detailed data from companies receiving the benefit.

These are just two examples of how bipartisan majorities have come together across the country to make sure that regular taxpayers are getting a good deal from business tax breaks. Georgia lawmakers can follow suit by exploring a few common sense tools, including some suggested specifically for the state by Pew, and drafting legislation when the General Assembly reconvenes next January. Otherwise, taxpayers can likely expect more of the same from their legislators in future years: a Wild-West scramble for tax breaks based more on backers’ claims than on objective evidence or thoughtful review.