The role of government in society is to enact policies that are needed to advance towards economic justice. Those policies include supporting Georgians’ basic needs (food shelter, healthcare, education), improving their household financial stability (living wages/stable resources to pay bills) and promoting their long-term economic security (ability to absorb shocks and plan for the future). One of the primary ways that government fulfills this responsibility is through a network of federal safety net programs that have been in place for decades, some administered by the state, designed to reduce poverty and provide support for vulnerable populations. These programs serve various functions, from providing income for seniors and people with disabilities, to helping families who earn low incomes afford food, healthcare and temporary financial assistance. These programs depend on two critical actors, the federal government and the State of Georgia, and that they share their dual responsibility to work together for the good of all Georgians. In H.R. 1, the federal reconciliation bill, the federal government shirks its responsibility to Georgians, leaving the state to continue to support Georgians with fewer resources.

The federal reconciliation bill (H.R. 1) signed into law on July 4, is one of the most regressive pieces of legislation in US history as it:[1]

- Pays for $1 trillion in tax reductions for those in the top 1% of wealth through over $1 trillion cuts to Medicaid, the ACA marketplace and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) over the next 10 years[2]

- Adds $3.6 trillion to the national deficit[5]

- Enacts an uncapped federal private school voucher tax credit, funneling public funds into private schools, and likely to cost at least $3 billion per year[6]

- Implements adjustments to Pell Grants and restrictions on federal student loans, with cuts of over $270.5 billion,[7] negatively impacting borrowers with low incomes[8]

At the state level, H.R. 1’s regressivity becomes clear as 73% in annual tax savings will go to Georgians who fall in the top 20% of highest-earning households.[9] In addition, cuts to basic assistance programs in Georgia are disguised by shifting costs to the state and expanding harmful work requirements. These changes will not only negatively impact Georgians’ health and well-being but will also threaten the resilience of local economies, especially in rural areas. Black families and individuals are overrepresented in Medicaid and SNAP, and Black Georgians are likely to bear the brunt of the cuts.[10] Georgia’s immigrant families are already often completely blocked from accessing these programs, and H.R. 1 tightens immigrant eligibility restrictions.[11]

H.R. 1 will also impact Georgia’s K-12 public schools and higher education institutions. In K-12, the federal private school voucher tax credit is the most notable change, which would accelerate the siphoning of public funds into private schools. It also has no cap, and the cost of the voucher program will likely grow every year as families get used to using the credit.[12] If Georgia opts in, private schools will see a financial boost with dollar-for-dollar tax credits for qualifying charitable contributions to scholarships at private schools.[13] In higher education, financial aid, namely student loans (graduate student loans and Parent PLUS loans), are restricted to fewer students, and repayment plans are restructured. Students who are financially marginalized are most likely to borrow money and will be disproportionately impacted by these changes.[14] The restructuring of repayment plans has been predicted to be especially difficult for borrowers with extremely low incomes given how the dynamics of poverty interact with the repayment rules.[15]

Overall, the legislation prioritizes large tax cuts for the wealthiest over health care and food for millions. It also sets the stage for higher interest rates[16] and reduced economic growth[17] caused by financing top-heavy tax reductions for a small share of wealthy Americans. This analysis includes a synopsis of the effects of the legislation’s provisions in Georgia across tax, health, food security and education.

Overview of Tax Policy Changes

H.R. 1 favors those already at the top of the economic ladder. Most Georgians, those with incomes among the first 60% of households, receive just 12% ($1.8 billion) of $15.2 billion in overall annual statewide tax savings.[18] This compares to 48% of overall tax savings directed to the top 5% of Georgia earners.[19] H.R. 1 also includes a modest increase to the Child Tax Credit (CTC) from $2,000 to a maximum of $2,200, along with new restrictions for children from immigrant families that require parents to produce a Social Security number when applying for the CTC. H.R. 1 also creates a new program (with no income criteria) to provide $1,000 accounts to newborn babies, which can voluntarily be claimed by U.S. citizens with babies born between 2025 and 2028.[20] Although the accounts are designed to incentivize early retirement savings, the proposal is structured to mirror other, more expansive plans for “Baby Bonds,” which could help put college, home ownership, or entrepreneurial endeavors closer within reach for more young adults.

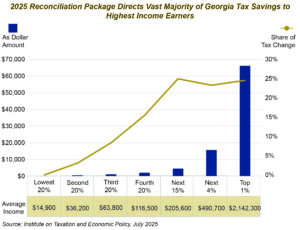

The following chart further details H.R. 1’s impact by household income.

Even before factoring in the effects of spending cuts on household income, the share of tax reductions received as a share of total income is heavily skewed. The top 5% would see savings equivalent to about 3.2% of their annual earnings, while the lowest 20% of Georgians would see savings of less than two-tenths of a percentage point, averaging $20 per year.[21] Including the effects of the measure’s spending cuts, the Penn Warton Budget Model estimates an overall reduction in income, after taking into account taxes and government payments, of 5.4% for the lowest earning 20% nationally, along with a 2.3% reduction for those in the next 20% of earners.[22] Those in the middle 20% would see an overall benefit of 0.1%, averaging $45 in net benefits.[23]

These tax savings are financed through increasing debt and cuts to core programs like health care and food assistance. Economic modeling forecasts that the legislation is likely to cause the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and wages to fall. Over 10 years, Penn Wharton estimates a 0.4% reduction in wages and a 0.3% reduction in GDP. These figures grow to a 3.4% reduction in wages and a 4.6% reduction in GDP after 30 years.[24]

Overview of Medicaid Changes

The decrease in federal Medicaid funding shifts more costs to the state.

Medicaid is a federal-state partnership that provides access to health coverage for Georgians with lower incomes. The program is jointly financed by the state and federal government. The federal government pays about 66% of the cost for health care benefits, and the state pays the remainder. In FY2026, the state expects to receive about $13 billion in federal Medicaid funds to support its Medicaid and PeachCare programs along with additional federal Medicaid funds for hospitals and providers through directed payment programs.[25] However, H.R. 1 puts a proportion of those federal funds at risk.

It is estimated that, over the next decade, federal Medicaid spending in the state will decrease by $6-$10 billion because of the Medicaid provisions in H.R. 1.[26] This reduction forces the state to a) raise additional revenue and seek other sources of state funding to cover the reduced federal funds, b) make cuts to the Medicaid program by: lowering provider reimbursement rates; limiting optional benefits like dental care for adults; restricting eligibility for optional populations such as children with disabilities covered under the Katie Beckett waiver;[27] and/or increasing cost-sharing for enrollees; or c) implement some combination of filling funding gaps and making cuts.

H.R. 1 hamstrings state financing of Medicaid and limits the state’s ability to support rural and safety net hospitals.

There are two primary ways in which H.R. 1 puts downward pressure on Georgia’s state budget:

- Freezes state provider taxes [28] at current rates and prohibits states from establishing new provider taxes

- The revenue generated from Georgia’s ambulance, nursing home and hospital provider taxes covers 12% of the state’s share of Medicaid funding (excluding PeachCare).[29] These provider taxes also help fund the non-federal share of the state’s directed payment programs.[30] Georgia’s provider taxes are already at the lowest rate (3.5%) compared to 48 other states.[31] Freezing existing state provider taxes and prohibiting new provider taxes deprives Georgia of an important tool for filling holes in the state’s health care budget during economic downturns and for responding to ever-shifting health care system needs.

- Caps new directed payment programs (DPPs)[32] in states like Georgia that have not expanded Medicaid[33] at 110% of the Medicare rate and requires existing DPPs with commercial rates to reduce payments by 10% each year until they reach 110% of the Medicare rate

- In general, Medicaid reimburses health care providers at a lower rate than Medicare or commercial plans. DPPs allow states to more adequately compensate providers and provide a critical financial boost to safety net and rural hospitals. According to the Georgia Hospital Association, reducing DPP payments to the Medicare rate would reduce Georgia’s hospital-based DPP funding by over 70% and entirely shut down Georgia’s two largest DPPs – GA-STRONG which supports teaching hospitals and GA-AIDE which supports Grady Hospital and Augusta University Medical Center.[34] Without these supplementary payments, some rural and safety net hospitals, which already operate on thin or negative margins, may be forced to reduce services or close altogether.

H.R. 1 adds complexity to the existing Medicaid work reporting requirement and increases pressure on Georgia’s eligibility and enrollment system.

Since July 2023, Georgia has been the only state in the nation that requires low-income, non-pregnant, non-elderly adults to report 80 hours per month of employment, higher education, volunteering or other activities in order to qualify for Medicaid.[35] Georgia’s program currently has no long-term reporting exemptions. However, if Georgia is required to align with H.R. 1’s Medicaid ‘community engagement’ requirement, more Georgians, such as parents of children 13 and under, veterans and people caring for a disabled relative, may be able to gain Medicaid coverage under work reporting exemptions. The new law may also require Georgians currently covered by traditional Medicaid without reporting requirements, such as women enrolled in the Planning for Healthy Babies program or very low-income parents, to submit verification of their compliance with or their exemption from the work reporting requirement. All these changes will likely result in Georgia spending even more on costly technology upgrades to the state’s outdated eligibility and enrollment system and increase the untenable workload for Georgia’s frontline eligibility caseworkers. [36] [37] [38]

All Georgians will be impacted, but rural Georgians, Georgians of color and immigrants will experience the greatest harm.

Medicaid and PeachCare cover about 2 million Georgians, of which about 70% are children under the age of 19.[39] Medicaid finances 45% of births and over 70% of nursing home stays and helps a range of Georgians with lower incomes see the doctor, fill prescriptions and get access to preventive care.[40] [41] The potential downstream impact of H.R. 1’s Medicaid provisions such as coverage losses and financial strain on hospitals and providers will disproportionately harm three groups of Georgians: rural Georgians, Black and Latino Georgians, and some lawfully present immigrants. Due to factors related to long-standing economic disadvantage and structural discrimination,[42] [43] rural Georgians and Black and Latino Georgians are overrepresented in Georgia’s Medicaid program and are at greater risk for the harms created by H.R. 1.

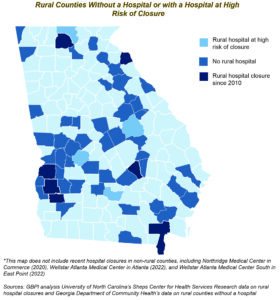

In addition, 53 of Georgia’s rural counties already do not have a hospital.[44] Research indicates that Fannin County Hospital, Flint River Community Hospital (Macon County), Irwin County Hospital and Washington County Regional Medical Center are estimated to have the highest likelihood of reducing services or closing due to H.R. 1[45] Of those four hospitals, two are in communities with a higher proportion of Black residents than the state average.[46] Hospital service reductions and closures impact everyone who receives care at the hospital, no matter their insurance status, and eliminates jobs for community members employed there. Lastly, under H.R. 1 state Medicaid programs are now prohibited from covering refugees; foreign-born individuals granted parole for at least one year; individuals granted asylum or related relief; immigrants who are abused spouses or children; and immigrant victims of trafficking.[47]

Overview of SNAP Changes

SNAP provides food assistance to 1.4 million Georgians with low incomes[48] and reduces the likelihood of being food insecure by 30%.[49] Yet H.R. 1 would cut SNAP by nearly $200 billion[50] across the country and includes changes that undermine SNAP’s effectiveness at reducing food insecurity. The new structure of the program, the expansion of harmful work reporting requirements, and the eligibility restrictions for many lawfully present immigrants would make it harder for people to afford the cost of food. These factors also put pressure on the state budget and harm local economies that rely on SNAP benefits.

SNAP cuts have been disguised by shifting costs to the states.

Many of the changes to the SNAP program found in H.R. 1 disguise the cuts by shifting costs to the states and saddling them with additional and unprecedented expenses. Georgia’s leaders will now have to make tough decisions to raise revenue or make changes that reduce access and services.

Under H.R. 1, for the first time states must cover a share of the cost of SNAP benefits based on a sliding scale. If a state pays and how much a state pays will be based on the state’s payment error rates, which are overpayments or underpayments to clients based on caseworker or client mistakes. Starting in Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2028, states with error rates of 6% or greater will have to cover a share of SNAP benefits. States can choose to be measured on error rates from 2025 or 2026 for the first year of implementation, which is 2028.[51] In subsequent years, they must use error rates from three years prior. If the state has an error rate:

- Between 6% and 8%, it will be required to pay 5% of the SNAP benefits.

- Between 8% and 10%, it will be required to pay 10% of SNAP benefits.

- Greater than 10%, it will be required to pay 15% of SNAP benefits.

However, the law temporarily postpones implementation of this provision for states with an error rate in FFY 2025 or FFY 2026 that is 13.33% or more. If a state meets this threshold in FFY 2025 implementation will be delayed until fiscal year 2029; if it applies to a state’s FFY 2026 error rate, implementation will be delayed until FFY 2030.[52] Georgia’s FFY 2024 error rate was 15.65.[53] If the state maintains this high payment error rate in FFY 2025 or FFY 2026, it would be eligible for a later start date.

If Georgia has an error rate that requires the state to contribute to SNAP benefits, the amount could run into the hundreds of millions. Based on current levels of spending, a 5% cost shift would mean about $162 million; a 15% cost shift could mean $487 million.[54] If states cannot afford the new cost, they are likely to lower their expenses by making it harder to access food assistance or they can opt out of the program altogether. Both scenarios would create challenges for families with low incomes to afford groceries.

Additionally, H.R. 1 increases the state’s share of administrative costs from 50% to 75% starting in 2027. To illustrate how much this could cost, if the state wanted to maintain the total administrative spending from FFY 2023, it would have to pay an additional $55 million yearly.[55]

H.R. 1 expands SNAP work reporting requirements.

Georgia’s SNAP program currently has a work requirement for adults aged 18 to 54 not living with children and without a verified disability. Many adults enrolled in SNAP already work, but for low wages and have inconsistent scheduling. If they are not working, they are between jobs, live in an area with limited access to jobs, are caring for a family member, or are enrolled in school or have a disability, which prevents them from working.[56] Research studies find little evidence of work reporting requirements leading to economically secure jobs; instead, these requirements kick people off basic needs programs.[57] H.R. 1 could reduce SNAP benefits for tens of thousands of people living in a household where an adult is subject to the new work reporting requirement.

SNAP current work reporting requirements will expand to new groups of people while also seeing a reduction in exceptions. The changes include:

- Increasing the age of adults expected to comply with work rules from 54 to 64

- Adding parents, grandparents and caregivers of children aged 14 to 17

- Eliminating exemptions for veterans, unhoused people and youth aged out of foster care

- Narrowing exemption waivers for certain areas of the state to only consider areas with an average unemployment rate of 10% or more

In Georgia, about 96,000 adults will be newly subject to the work reporting requirements and at risk of losing SNAP entirely if they cannot meet the requirements.[58] Approximately 154,000 people could lose at least some of their benefits if an adult in their household is unable to fulfill a reporting requirement.[59]

H.R. 1’s other changes take food away from immigrants, make food less affordable and deprive individuals of key information.

H.R. 1 includes other changes that would make it harder for people to afford nutritious food and access nutrition education, as it:

- Prevents many legally present “qualified” immigrants who are not Lawful Permanent Residents from receiving SNAP. This includes low-income legally present immigrants who have been granted humanitarian protections, including refugees, people granted asylum, and certain survivors of domestic violence or labor or sex trafficking, among others.[60] H.R. 1 included no implementation date, so the start of such restrictions is unclear.

- Freezes future increases to the cost of the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP)[61] – a USDA plan that outlines a nutritionally adequate diet at a very low cost. The new law returns to the previous standard of only adjusting SNAP benefits relative to inflation. With food prices rising fast, SNAP benefits may be less able to keep up with growing grocery costs.

- Eliminates the National Education and Obesity Prevention Grant Program, also known as SNAP-Ed program, which provides nutrition and obesity prevention education.[62]

Overview of Education Changes

H.R. 1 will make nationwide changes to K-12 and higher education exacerbated by the withholding of funds that Congress already allocated to students in need.

Enacts an uncapped federal private school voucher tax credit, like Georgia’s Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit,[63] funneling public dollars into private schools.

The federal private school voucher tax credit is available to states that opt into the program, although it is not clear who will make the decision to opt in on the state level.[64] The voucher will provide dollar-for-dollar credit on qualifying charitable contributions to tax exempt state and local scholarship granting organizations up to $1,700 annually. “Scholarship” is the money allocated to a student after a taxpayer contributes to a scholarship granting organization. The scholarship can be used for educational expenses such as private or religious school tuition for students whose parents/families earn up to 300% of an area’s median gross income, which is variable by county and city. Ultimately, this means that most Georgia families would qualify for the voucher. The voucher will take effect in January 2027. There is no limit on the total amount that the federal government can spend on the program,[65] and it is likely to cost at least $3 billion per year with costs rising over time as families become accustomed to using the voucher.[66]

It is estimated that around 1.9 million Georgians will take advantage of the voucher.[67] [68] It is unclear how Georgians might use the federal voucher in conjunction with the Georgia Promise Scholarship (which takes effect this year) or other Georgia voucher programs, which have already diverted $1.3 billion in state public funds into private schools between 2008 and 2021.[69]

The federal government is withholding $6 billion in federal funds already allocated to serve vulnerable Georgia students.

On June 30th this year, one day before school districts across the nation were set to receive federal appropriations totaling over $6 billion, the U.S. Department of education informed schools that certain program funding would be held back, “pending review.” Approximately $223,888,870 is being withheld from Georgia.[70] The following three programs will be among the most impacted:[71]

- Title I-C: for migrant education, funds programs meeting the special educational needs of children of migrant agricultural workers. ($9,272,377, Title I-C funds supported over 5,000 Georgia students in 2022-2023)[72]

- Title III-A: for English-learner services, supports English Learners (ELs), including immigrant children and youth, in achieving English proficiency, academic excellence, and meeting state standards. ($21,500,979, Title III-A funds supported over 65,000 Georgia students in fiscal year 2024)[73]

- Title IV-B: for before- and after-school programs: this program supports low-performing schools by establishing or expanding community learning centers that provide academic enrichment opportunities during non-school hours for children, especially students who attend low-performing or high-poverty schools. ($47,106,295)

Changes to federal financial aid programs will both negatively affect vulnerable Georgians and provide modest benefits to them.

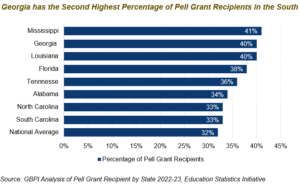

Federal financial aid programs are critical for Georgians. In 2023, there were approximately 228,026 students in Georgia who received the Pell Grant. Georgia is ranked number seven in the nation and is only second (tied with Louisiana) behind Mississippi with the highest percentage of Pell Grant recipients in the south.[74]

The final version of H.R. 1 included fewer harmful changes to the Pell Grant program than the original House bill while incorporating some modest improvements.

- A reduction in Pell Grant eligibility: This reduction is estimated to save the government $160 million over the next 10 years;[75] the following will no longer be Pell-eligible:

- Students and their families with income and assets that are calculated through their Student Aid Index (a formula-based index to determine Pell Grant eligibility) to be over twice the amount of the maximum Pell Grant ($144 million saved)

- Those who receive other non-federal grant aid like institution or state financial aid that together equal or exceed the student’s cost of attendance ($16 million saved)

- A small increase in Pell Grant Funds: Due to the projected $70 billion Pell Grant shortfall taking place over the next 10 years, the reconciliation bill provides an additional $10.5 billion.[76] These funds will be used to shore up funding for the Pell Grant program for the 2025-26 school year.

- Creation of the Workforce Pell Grant: The Workforce Pell Grant expands access to short postsecondary education programs with 150-600 hours or 8-15 weeks of instruction for programs that prepare students for “high-skill and high-wage” jobs. This program is estimated to cost $275 million over the next 10 years.[77]

Given the large number of Georgians who receive Pell, these adjustments will affect Georgia students, but the exact impact is unclear.

Student loan programs will remain the same for students enrolled in undergraduate programs. This is true except for loan limits that will be prorated for students who are enrolled on a less-than-full-time basis, based on the number of credits taken below full-time. The most noteworthy changes are related to the Grad/Parent PLUS Loan. Those provisions include:

- A discontinuation of Grad PLUS Loans: Beginning, July 1, 2026, the Grad PLUS Loan program will no longer be available to borrowers. Many Georgians rely on Grad Plus Loans to pay for college, approximately 12,681 awards were given in the 2023-24,[78] up from 9,157 in the 2013-14 school year.[79]

- Graduate student loan limits: Institution of new loan limits for graduate students. For example, non-professional graduate students (i.e., Masters and Doctor of Philosophy) will be limited to $20,500 per year in unsubsidized Stafford loans and a $100,000 lifetime limit. Additionally, professional students in medical and law school are limited to $50,000 per year and a $200,000 lifetime limit.

- Annual Parent PLUS loan limit: The aggregate limit for Parent PLUS loans goes from no limit to $65,000 per dependent student. Current students can continue receiving loans under the existing limits until the completion of their currently enrolled program.

- Reduction of the number of repayment options to just two. Two repayment options for new borrowers will be available on or after July 1, 2026. It is estimated that the changed loan repayment structure will save the federal government $270.5 billion over the next 10 years.[80]

- Standard Repayment Plan: allows students to pay back their loans with repayment based on the amount borrowed.

- Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP): the new income-driven repayment (IDR) plan would steadily increase the percentage of the borrower’s income used to calculate the monthly payment amount from 1% to 10%. RAP is projected to increase monthly student loan payments compared to existing IDR plans like Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) and Income-based Repayment plans (IBR). Low-income borrowers will receive relief through government support; however, it has been shown that the RAP will likely result in more defaults and increased hardship for low-income borrowers compared to current IDR plans.[81]

Colleges will not only have fewer financial aid options to offer financially marginalized students, but H.R. 1 will also establish an unprecedented higher education accountability standard for some academic majors. This change will require that students earn more income than they would have if they had not completed the program. If not, the program will be at risk of losing its loan eligibility.

Conclusion

H.R. 1 is one of the most regressive federal bills in U.S. history. It represents a wholesale retreat from the federal government’s shared responsibility with the State of Georgia to protect the well-being of its people. By delivering $1 trillion in tax cuts to the top 1% while slashing more than $1 trillion from Medicaid and SNAP, the bill prioritizes wealth over welfare and leaves Georgia’s most marginalized residents, especially Black, Latino, and immigrant communities, to bear the burden. Georgians eligible for SNAP are also likely eligible for Medicaid, these are not isolated harms, these are compounding harms on Georgians who are already struggling. Georgia immigrants with humanitarian protections will now largely be excluded from both Medicaid and SNAP, and rural hospitals already on the brink face heightened risk of closure due to reduced funding and financial constraints imposed by the bill.

The consequences of H.R. 1 won’t just be immediate; they will compound over time. In addition to widening racial and geographic disparities, the legislation adds $3.6 trillion to the national deficit, undermines student financial aid, and restructures loan repayment plans in ways that will harm low-income borrowers across Georgia. Over the next 30 years, it is projected to drive down wages by 3.4% and shrink GDP by 4.6%, further destabilizing the economic future for working families.

When federal leaders choose cuts over care, the harm reverberates across communities and generations. While Georgia must do all it can to deploy the tools it has to support its people, it cannot and should not be asked to backfill this level of federal retreat alone. At GBPI, we will continue to monitor the impacts of this legislation and provide tools, research, and policy options so we can collectively advocate for a fairer, more equitable future.

In the Appendix, we have laid out the implementation timeline for H.R. 1’s Medicaid, SNAP and education provisions. You can also find key implementation dates here, provided by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Appendix

H.R. 1 Implementation Timeline

Medicaid

- Upon enactment

- Prohibits states from establishing new provider taxes or from increasing the rates of existing taxes

- Caps payment rate for state directed payment programs in non-expansion states like Georgia at 110% of the Medicare rate. Keeps in place state directed payments set at commercial rate approved prior to enactment for rural hospitals and prior to May 1, 2025, for all other providers.

- January 2026

- Eliminates federal ‘sign-on’ bonus for state’s that have yet to fully expand Medicaid to low-income adults as designed under the Affordable Care Act

- October 2026

- Establishes a rural health transformation program to provide $50 billion in grants to states between FY 2026 and FY 2030 to be used for payments to rural health care providers/hospitals

- Changes definition of qualified immigrants for Medicaid/PeachCare eligibility to Lawful Permanent Residents, certain Cuban and Haitian immigrants, citizens of Freely Associated States

- December 2026 (or December 2028 if demonstrating good faith effort)

- Implements Medicaid ‘community engagement’ requirement (also known as a work requirement)

- January 2028

- Reduces preexisting state directed payment programs set at commercial rate by 10% each year until they reach 110% of Medicare rate

SNAP

- Unspecified/effective upon enactment

- Expanded SNAP work reporting requirement

- SNAP restriction on certain immigrants

- October 2025

- The elimination of the National Education and Obesity Prevention Grant Program, also known as SNAP-Ed

- October 2026

- Re-evaluation of the Thrifty Food Plan; no benefit adjustment based on the re-evaluation.

- Increase of the state administrative costs from 50% to 75%

- October 2027

- Start of the cost-shift for states with error rates between 6% and 13.33%

- October 2028

- Delayed implementation of SNAP cost shift based on FFY 2025 error rates

- October 2029

- Delayed implementation of SNAP cost shift based on FFY 2026 error rates

Education

- July 2026

- Start of the 529 plan expansion to allow higher tax-free distributions for K-12 expenses for elementary and secondary schools; yearly withdrawal limit goes from $10,000/year to $20,000

- Workforce Pell Grant program will be available for short-term post-secondary programs

- Grad PLUS Loan Program will discontinue

- Graduate school loan limits will begin

- Parent PLUS loans annual limit will start

- New student loan borrowers will have two repayment plans available: Standard repayment plan and the Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP)

- January 2027

- Launch of the nationwide federal private school voucher tax credit for K-12

Endnotes

[1] Badger, E., Parlapiano, A., & Sanger-Katz, M. (2025, June 12). Trump’s big bill would be more regressive than any major law in decades (analysis of House-passed version). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/06/12/upshot/gop-megabill-distribution-poor-rich.html; analyses of Senate-passed version show similar regressivity, see sources below.

[2] Penn Wharton Budget Model. (July 8, 2025). President Trump-signed reconciliation bill: budget, economic, and distributional effects. https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2025/7/8/president-trump-signed-reconciliation-bill-budget-economic-and-distributional-effects

[3] Homan, M. (2025, July 14). The most draconian cuts imaginable’: Health care providers, advocates brace for Medicaid cuts. https://georgiarecorder.com/2025/07/14/the-most-draconian-cuts-imaginable-health-care-providers-advocates-brace-for-medicaid-cuts/

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Davis, C. (2025, July 6). Megabill takes cap off unprecedented private school voucher tax credit, potentially raising cost by tens of billions relative to earlier version. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/trump-megabill-expensive-private-school-vouchers/

[7] Congressional Budget Office. (2025, June 27). Cost Estimate, Table 8, Estimated budgetary effects of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Title VIII tab, cell O43. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cbo.gov%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2F2025-06%2F61533-hr0001-Sen-2025Recon-BEB.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

[8] Caldwell, T., Matsudaira, J., & McCann, C. (2025, July). Revamping the Republicans’ RAP repayment plan. American University, Postsecondary Education and Economics Research Center. https://www.american.edu/spa/peer/upload/revamping-rs-rap-repayment-plan_rpt_final-1.pdf

[9] Davis, C., Vela, J., & Hughes, J. (2025, July 2). Analysis of tax provisions in the senate reconciliation bill: National and state Level Estimates. (Georgia data). Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/analysis-of-tax-provisions-in-senate-reconciliation-bill/; state-by-state analysis, Georgia, Senate-Reconciliation-Bill-Numbers-Revised-7-2.xlsx

[10] Cid-Martinez, I., Moore, K. K., & Maye, A. A. (2025, April 2). Cuts to Medicaid will disproportionately hurt people of color and children. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/medicaid-cuts-will-disproportionately-hurt-people-of-color-and-children/; Cid-Martinez, I. (2025, April 29). Cuts to SNAP benefits will disproportionately harm families of color and children. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/cuts-to-snap-benefits-will-disproportionately-harm-families-of-color-and-children/

[11] USDA Food and Nutrition Service. SNAP eligibility for non-citizens. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/recipient/eligibility/non-citizen; Georgia Medicaid. Citizenship and residency FAQs. https://medicaid.georgia.gov/citizenship-and-residency-faqs

[12] Davis, C. (2025, July 6). Megabill takes cap off unprecedented private school voucher tax credit, potentially raising cost by tens of billions relative to earlier version. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/trump-megabill-expensive-private-school-vouchers/

[13] For an illustration of how this mechanism could work, see: Figure 1: Proposed flow of funds under the ECCA of 2025, in Davis, C. (2025, March 18). Shelter skelter: How the Educational Choice for Children Act would use tax avoidance to fuel school privatization. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/educational-choice-for-children-act-tax-avoidance-private-school-vouchers/

[14] Perry, A. M., Steinbaum, M., & Romer, C. (2021, June 23). Student loans, the racial wealth divide, and why we need full student debt cancellation. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/student-loans-the-racial-wealth-divide-and-why-we-need-full-student-debt-cancellation/; Caldwell, T., Matsudaira, J, & McCann, C. (2025, July). Revamping the Republicans’ RAP repayment plan. American University, Postsecondary Education and Economics Research Center. https://www.american.edu/spa/peer/upload/revamping-rs-rap-repayment-plan_rpt_final-1.pdf

[15] Caldwell, T., Matsudaira, J., & McCann, C. (2025, July). Revamping the Republicans’ RAP repayment plan. American University, Postsecondary Education and Economics Research Center. https://www.american.edu/spa/peer/upload/revamping-rs-rap-repayment-plan_rpt_final-1.pdf

[16] Yale University, The Budget Lab. (2025, June 10). Interest costs associated with the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/interest-costs-associated-one-big-beautiful-bill-act

[17] Penn Wharton Budget Model. (July 8, 2025). President Trump-signed reconciliation bill: budget, economic, and distributional effects. https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2025/7/8/president-trump-signed-reconciliation-bill-budget-economic-and-distributional-effects

[18] Davis, C., Vela, J., & Hughes, J. (2025, July 2). Analysis of Tax Provisions in the Senate Reconciliation Bill: National and State Level Estimates. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/analysis-of-tax-provisions-in-senate-reconciliation-bill/

[19] Ibid.

[20] Carrns, A. (2025, July 11). How the $1,000 ‘Trump Accounts’ for newborns will work. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/11/your-money/trump-accounts-newborns.html

[21] Davis, C., Vela, J., & Hughes, J. (2025, July 2). Analysis of Tax Provisions in the Senate Reconciliation Bill: National and State Level Estimates. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/analysis-of-tax-provisions-in-senate-reconciliation-bill/

[22] Penn Wharton Budget Model. (July 8, 2025). President Trump-signed reconciliation bill: budget, economic, and distributional effects. https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2025/7/8/president-trump-signed-reconciliation-bill-budget-economic-and-distributional-effects

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Chan, L. (2025, May 21). House-passed federal budget legislation proposes historical Medicaid cuts with serious fiscal impacts for Georgia. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/federal-budget-legislation-proposes-largest-medicaid-cuts-with-serious-fiscal-impacts-for-georgia/

[26] Euhus, R., Williams, E., Burns, A., & Rudowitz, R. (2025, July 1). Allocating CBO’s estimates of federal Medicaid spending reductions across the states: Senate reconciliation bill. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/allocating-cbos-estimates-of-federal-medicaid-spending-reductions-across-the-states-senate-reconciliation-bill/

[27] Georgia Medicaid. TEFRA/Katie Beckett. https://medicaid.georgia.gov/programs/all-programs/tefrakatie-beckett

[28] Burns, A., Hinton, E., Williams, E., & Rudowitz, R. (2025, March 26). 5 key facts about Medicaid and provider taxes. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/5-key-facts-about-medicaid-and-provider-taxes/#:~:text=States%20are%20permitted%20to%20finance,and%20hospitals%20(45%20states)

[29] Chan, L. (2025, May 21). House-passed federal budget legislation proposes historical Medicaid cuts with serious fiscal impacts for Georgia. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/federal-budget-legislation-proposes-largest-medicaid-cuts-with-serious-fiscal-impacts-for-georgia/

[30] Ibid.

[31] Burns, A., Hinton, E., Williams, E., & Rudowitz, R. (2025, March 26). 5 key facts about Medicaid and provider taxes. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/5-key-facts-about-medicaid-and-provider-taxes/

[32] Georgia Department of Community Health. State directed payment programs. https://dch.georgia.gov/programs/state-directed-payment-programs

[33] KFF. (2025, May 9). Status of Medicaid expansion decisions. https://www.kff.org/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions/

[34] Georgia Hospital Association. Georgia hospital directed payment programs: Delivering access to care for Georgians. [Fact Sheet]

[35] Chan, L. (2024, October 29). Georgia’s Pathways to Coverage program: The first year in review. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgias-pathways-to-coverage-program-the-first-year-in-review/

[36] Ibid.

[37] Lucas, L. (2025, April 1). Legislation could require plan to address backlog of federal benefit cases in Georgia. 11 Alive News. https://www.11alive.com/article/news/state/georgia-lawmakers-legislation-provision-to-address-medicaid-snap-tanf-benefits-backlog/85-df10c637-cc89-4ed4-adda-f4165e404ec7

[38] Coker, M. (2025, February 19). Georgia touts its Medicaid experiment as a success. The numbers tell a different story. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/georgia-medicaid-work-requirement-pathways-to-coverage-hurdles

[39] GBPI analysis of February 2025 state Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data available on data.medicaid.gov

[40] KFF. (2023). Births financed by Medicaid by metropolitan status. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/births-financed-by-medicaid

[41] KFF. (2024). Distribution of certified nursing facility residents by primary payer source. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-of-certified-nursing-facilities-by-primary-payer-source/

[42] Yearby, R., Clark, B., & Figueroa, J. F. (2022, February). Structural racism in historical and modern U.S. health care policy. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01466

[43] Braveman, P., Acker, J., Arkin, E., Badger, K., & Holm, N. (2022, June). Advancing health equity in rural America. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2022/06/advancing-health-equity-in-rural-america.html

[44] Chan, L. (2024, March 4). The state of Georgia’s healthcare system. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/statehealthcaresources/

[45] Holmes, M., Malone, T. L., & Pink, G. H. (2025, June 10). Letter from researchers at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to Minority Leader Schumer and Ranking Members Markey, Merkley, and Wyden. https://www.markey.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/sheps_response.pdf

[46] GBPI analysis of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill data on rural hospital closures and 2023 U.S. Census estimates of Black population by county

[47] Altman, H., Broder, T., & D’Avanzo, B. (2025, July 8). Policy brief: The anti-immigrant policies in Trump’s final “Big Beautiful Bill,” explained, restrictions on immigrants’ health and nutrition. National Immigration Law Center. https://www.nilc.org/resources/the-anti-immigrant-policies-in-trumps-final-big-beautiful-bill-explained/

[48] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2025, January 21). Georgia, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/snap_factsheet_georgia.pdf

[49] Ratcliffe, C., & McKernan, S. M. (2010, April). How much does SNAP reduce food insecurity? US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84335#:~:text=The%20results%20suggest%20that%20receiving,of%20reducing%20food%2Drelated%20hardship

[50] Davis, C. (2025, July 7). Top 1% to receive $1 trillion tax Cut from trump megabill over the next decade. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/top-1-to-receive-1-trillion-tax-cut-from-trump-megabill-over-next-decade/; Congressional Budget Office. (2025, June 28). Cost Estimate, Estimated budgetary effects of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Title I tab, Cell O59 https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cbo.gov%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2F2025-06%2F61533-hr0001-Sen-2025Recon-BEB.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

[51] Error rates for a given year are released in following year. For example, USDA released the error rates for federal fiscal year 2024, in June 2025.

[52] One Big Beautiful Bill, Title 1 U.S.C. § section 10105 (2025).

This provision was specifically included to help gain the vote of the one senator from Alaska. See: Badger, E. (2025, July 2). Republicans want to cut food stamp errors. Their bill could backfire. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/02/upshot/republicans-food-aid-alaska.html.

[53] U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service. (2025, June 30). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Payment error rates fiscal year 2024. https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-fy24QC-PER.pdf.

[54] Bergh, K., Rosenbaum, D., & Tharpe, W. (2025, May 28). House reconciliation bill proposes deepest SNAP cut in history, would take food assistance away from millions of low-income families. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/house-reconciliation-bill-proposes-deepest-snap-cut-in-history-would-take

[55] Finch Floyd, I. (2025, May 22). The House Agricultural Committee proposes unprecedented changes to the SNAP program that would increase food insecurity. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/the-house-agriculture-committee-proposes-unprecedented-changes-to-the-snap-program-that-would-increase-food-insecurity/

[56] Butcher, K. F., & Whitmore Schanzenbach, D. (2018, July 24). Most workers in low-wage labor market work substantial hours, in volatile jobs. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/most-workers-in-low-wage-labor-market-work-substantial-hours-in-volatile

[57] Pavetti, L. (2018, April 3). Evidence doesn’t support claims of success of TANF work requirements. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/evidence-doesnt-support-claims-of-success-of-tanf-work-requirements; Gray, C., Leive, A., Prager, E., Pukelis, K., & Zaki, M. (2023). Employed in a SNAP: The impact of work requirements on program participation and labor supply. American Economic Association Journal, 15(1), 306-341. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20200561; Feng, W. (2021). The effects of changing SNAP work requirement on the health and employment outcomes of able-bodied adults without dependents. Journal of the American Nutrition Association, 41(3), 281-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2021.1879692; Han, J. (2022). The impact of SNAP work requirements on labor supply. Labour Economics, 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2021.102089; Ku, L., Brantley, E., & Pillai, D. (2019). The effects of SNAP work requirements in reducing participation and benefits from 2013 to 2017. American Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1446-1451. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305232#:~:text=Expansions%20of%20work%20requirements%20caused%20about%20600%E2%80%89000%20participants,after%20work%20requirements%20were%20imposed.%20Public%20Health%20Implications; Stacy, B., Scherpf, E., & Jo, Y. (2018, December 14). The impact of SNAP work requirements. working paper, https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2019/preliminary/paper/Z8ZhzBZt

[58] Llobrera, J., Rosenbaum, D., & Nchako, C. (2025, June 27). Senate Agriculture Committee’s revised work requirement would risk taking away food assistance from more than 5 million people: State estimates. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/senate-agriculture-committees-revised-work-requirement-would-risk-taking

[59] Ibid.

[60] Altman, H., Broder, T., & D’Avanzo, B. (2025, July 8). Policy brief: The anti-immigrant policies in Trump’s final “Big Beautiful Bill,” explained, restrictions on immigrants’ health and nutrition. National Immigration Law Center. https://www.nilc.org/resources/the-anti-immigrant-policies-in-trumps-final-big-beautiful-bill-explained/

[61] USDA, Food and Nutrition Service. (2025, January 28). SNAP and the Thrifty Food Plan. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/thriftyfoodplan

[62] USDA. SNAP-Ed connection. https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/about#header1

[63] Griffin, G. S., & Kieffer, L. (2023, June). Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit: Economic analysis. Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. https://www.audits.ga.gov/ReportSearch/download/29827; Professional Association of Georgia Educators. (2025, June 27 updated 2025, July 10). Federal update: “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act, summary. https://www.pagelegislative.org/post/federal-update-one-big-beautiful-bill-act-summary

[64] Arundel, K. (2025, July 8). 3 things to know about school choice in the ‘One Big, Beautiful Bill.’ K-12 dive. https://www.k12dive.com/news/3-things-to-know-about-school-choice-in-the-one-big-beautiful-bill/752367/

[65] Professional Association of Georgia Educators. (2025, July 10). Federal update: “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act, summary. https://www.pagelegislative.org/post/federal-update-one-big-beautiful-bill-act-summary

[66] Davis, C. (2025, July 6). Megabill takes cap off unprecedented private school voucher tax credit, potentially raising cost by tens of billions relative to earlier version. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/trump-megabill-expensive-private-school-vouchers/

[67] Ibid.

[68] US Census Bureau, Quick Facts. Georgia, July 1, 2024 population estimate (11,180,878) https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/GA/PST045223; US Census Bureau, US and world population clock (340,110,988, July 1, 2024 population) https://www.census.gov/popclock/; Georgia has 3.2% of the US population; this figure was used to extrapolate how many Georgia taxpayers out of 59 million taxpayers nationally might avail themselves of the voucher.

[69] Young, A. (2025, June 30). Georgia education primer for state fiscal year 2026. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgia-education-primer-for-state-fiscal-year-2026/

[70] DiNapoli, Michael A., & Griffith, M. (2025, June 30). States face uncertainty as an estimated $6.2 billion in K-12 funding remains unreleased: Here’s the fiscal impact by state. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/states-face-uncertainty-k-12-funding-remains-unreleased

[71] For an overview of each program and current allocations to Georgia, see: US Department of Education. Migrant education, Title I, Part C. https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/formula-grants/formula-grants-special-populations/migrant-education-program-title-i-part-c-state-grants; English language acquisition state grants, Title III, Part A. https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/formula-grants/formula-grants-special-populations/english-language-acquisition-state-grants-mdash-title-iii-part-a; Nita M. Lowey 21st century community learning centers, Title IV, Part B. https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/formula-grants/school-improvement-grants/nita-m-lowey-21st-century-community-learning-centers-title-iv-part-b

[72] US Department of Education, Ed Data Express. Migratory children who receive services funded by the Migrant Education Program (MEP), 2022-2023. https://eddataexpress.ed.gov/download/data-builder/data-download-tool?f%5B0%5D=population%3AMigratory%20Students&f%5B1%5D=state_name%3ADISTRICT%20OF%20COLUMBIA&f%5B2%5D=state_name%3AGEORGIA&f%5B3%5D=state_name%3ANEW%20MEXICO&f%5B4%5D=state_name%3ANEW%20YORK&f%5B5%5D=state_name%3ASOUTH%20DAKOTA&page=0%2C1

[73] Craven, M. (2025, March). What federal education funding means for schools – a look at federal funding in Georgia and Texas. Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA). https://www.idra.org/resource-center/what-federal-education-funding-means-for-schools-a-look-at-federal-funding-in-georgia-and-texas/#:~:text=More%20than%20$1.8%20billion%20in,703%2C000%20students%20with%20disabilities;%20and

[74] Hanson, M. (2024, November 4). Pell Grant Statistics [2023]: How many receive per year. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/pell-grant-statistics

[75] Congressional Budget Office. (2025, June 27). Cost Estimate, Table 8, Estimated budgetary effects of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Title VIII tab, Cell O69 and Cell O72. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cbo.gov%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2F2025-06%2F61533-hr0001-Sen-2025Recon-BEB.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

[76] Ibid. Cell O77.

[77] Ibid. Cell O73.

[78] National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities. (2025, January). Federal student aid summary: Representative Earl Carter Congressional District 1, Georgia. (also providing GA-wide data for 2023-2024). https://www.naicu.edu/media/3aja0clx/2024-congressional-districts-ga.pdf

[79] National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities. (2014). Federal student aid programs 2013-2014, Georgia. https://www.naicu.edu/media/acxfemom/20140129_2013-14_ga_state_total.pdf

[80] Congressional Budget Office. (2025, June 27). Cost Estimate, Table 8, Estimated budgetary effects of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Title VIII tab, Cell O43 https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cbo.gov%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2F2025-06%2F61533-hr0001-Sen-2025Recon-BEB.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

[81] Caldwell, T., Matsudaira, J., & McCann, C. (2025, July). Revamping the Republicans’ RAP repayment plan. American University, Postsecondary Education and Economics Research Center. https://www.american.edu/spa/peer/upload/revamping-rs-rap-repayment-plan_rpt_final-1.pdf