This report was co-authored by Jariel Davis, a fellow in the Southern Education Leadership Initiative, a program within the Southern Education Foundation.

Every year, the Georgia Budget & Policy Institute (GBPI) distributes a survey to each public school superintendent in the state to collect information on the effects of education funding on individual school districts, necessary improvements and the way policymakers best support students across Georgia. This year, school superintendents or other central office staff from 94 of Georgia’s 224 school districts and individual state-authorized public charter schools responded to the survey, representing 56% of all public school students in the state. The participants serve a representative sample of Georgia’s learners, with districts ranging vastly in size, geography and the student populations they support.

The following report summarizes findings from the survey focusing on four key areas: 1) school employee salaries, 2) impact of inflation, 3) health care benefits and 4) funding to educate students living in poverty. Insights from school leaders highlight the consequences of implemented policies to K-12 public education in Georgia. It brings understanding to critical information on school finances, under-reported impacts of state policies on public education and the need for additional funding for specific populations.

Quotes are used throughout the report to highlight specific perspectives and common themes. Survey respondents’ names, titles and districts have been used with permission.

Based on the results, Georgia stakeholders should:

- Create an Opportunity Weight in the school funding formula to support students in poverty.

- Increase state investment in pupil transportation.

- Support schools with employer portion of non-certified employee health insurance.

Employee Salaries

For the second consecutive year, the Georgia General Assembly passed a budget with a $2,000 raise to the state salary schedule. The teacher salary schedule determines the base pay and scheduled raises based on years of experience and level of educational attainment. However, school districts have broad flexibility to dictate employee salaries as district leaders are not legally compelled to implement raises or if the finances are available, cap a raise at $2,000. Local property taxes, which comprised 39% of public education budgets statewide in fiscal year (FY) 2022, can vary widely between districts based on property values.[1] Because state funding only accounts for 47% of local school finances, a school system must reallocate funds from local taxes to cover costs for staff raises. The different resources of schools across this state are illustrated in how, or whether, teacher pay has been raised by increased state funding.

We appreciate the lawmakers recognizing the importance of our teacher’s [sic] role however, pay increase puts a financial hardship on school systems due to QBE not covering all positions and a continuous increase in health benefits.

– Dr. Vickie Reed, Superintendent, Brooks County Schools

What will the salary of a first-year teacher with a bachelor’s degree be in your district in FY 2024? What was the salary of a first-year teacher with a bachelor’s degree … in your district in FY 2023?

The average reported teacher salary at this level will increase by $2,400 this year and average starting pay in FY 2023 was $42,070, ranging between $37,000 and $53,342. This school year, the average reported salary is $44,389, with the lowest reported salary being $39,092 and the highest being $58,000. Three districts reported they would not increase salaries, and one district reported a salary increase of half the amount proposed by the state. In contrast, eight districts reported a salary increase of at least double the $2,000 from the state, with the highest increase of $5,080. Open responses show school leaders are willing to give raises to their staff but are nervous about their stretched budgets.

The QBE formula attempts to address most needs for districts. But the funding for a position (teacher, counselor, etc.) does not cover the cost associated with hiring staff for those positions. Schools are looked at to provide services and meet needs that far exceed what schools were asked to do when the QBE formula was created (nursing, mental health, etc.)

– Charlton County Schools

What is the starting pay (per hour) for a bus driver in your district in FY 2024?

Teachers are not the only professionals contributing to the education of Georgia’s students. Every year, 933,000 students take a bus to and from the school.[2] This massive public transportation system relies on bus drivers and monitors to safely transport children 680,000 miles daily and 123 million miles annually.[3] Survey respondents reported an average hourly pay of $18.40 per hour, ranging between $10 and $32. Eleven percent (8 respondents) reported hourly wages less than $15 per hour. For districts that reported yearly salaries, the average was $14,388, with some drivers and monitors making as little as $10,490. The top end of the range is $34,025 annually.

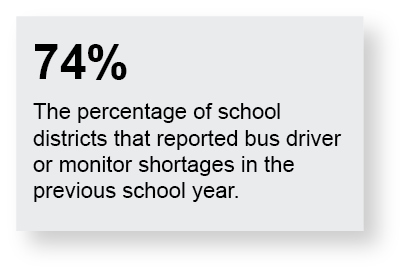

Did your district experience bus driver/monitor employment shortages in FY 2023?

Did your district experience bus driver/monitor employment shortages in FY 2023?

Considering the pay it is little surprise that 74% of school districts reported bus driver or monitor shortages in the previous school year. State funding for pupil transportation has been stagnant for two decades, forcing districts to shoulder an increasing cost burden.[4] Without adequate wages and funding for school bus replacement, bus routes are longer or missing while students’ safety is jeopardized.[5]

Is there something about teacher/employee pay and state funding you wish that the general public or lawmakers knew? Please explain.

A multitude of requirements continue to be placed on school systems, but funding for the positions to help with implementation of such requirements is essentially non-existent.

– Jennifer Brown, Superintendent, Early County School System

Until teacher and bus driver pay begins to catch up with inflation, we will continue to have shortages.

– Brantley County School District

The general public needs to know that there are so many systems in this state that just cannot raise money when needed. As the state adds cost to local systems, like teacher raises and health insurance costs, the local millage income and then if you try to adjust the tax rate, it just cannot cover these costs without sacrificing other costs somewhere. Since salaries and benefits already take 80+% of local budgets where do you take it from.

– Allen Fort, Superintendent, Taliaferro County Schools

Impact of Inflation

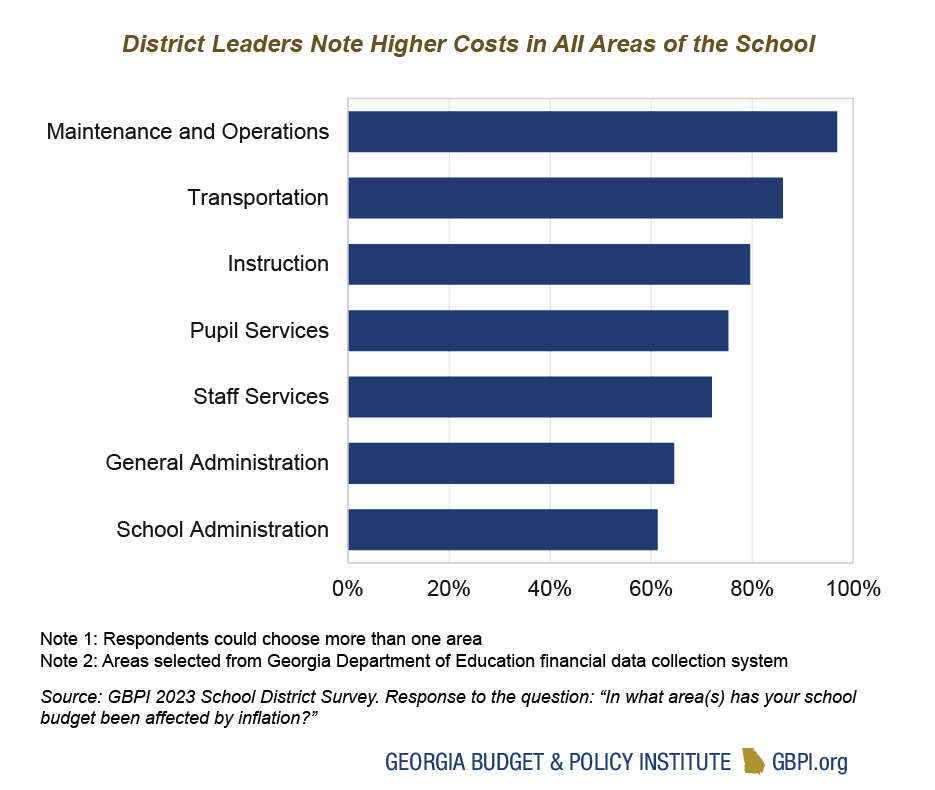

In what area(s) has your school budget been affected by inflation?

School budgets are not immune from the highest increase in the cost of goods in 40 years.[6] Every traditional school district and charter school surveyed reported that their budgets had been affected by the rise in cost caused by inflation. Of the budget areas used by the Georgia Department of Education, 97% of respondents reported increased costs in maintenance and operations. Next, the vast majority (86%) also reported increased costs associated with transportation. The following chart represents the results.

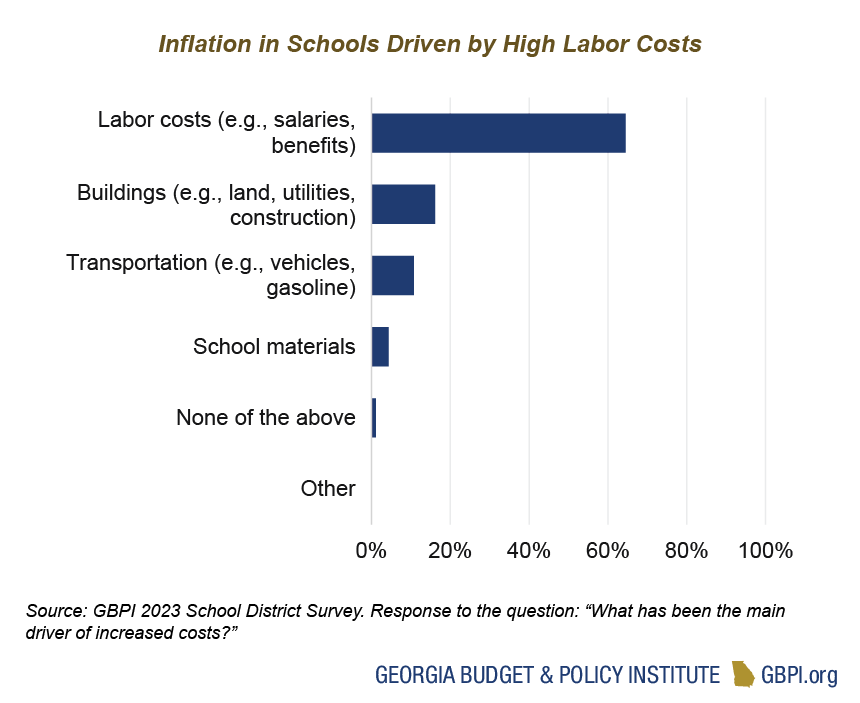

What has been the main driver of increased costs?

Labor costs are the primary driver of increased costs across the budgetary areas mentioned above, according to the survey. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of respondents noted the budgetary pressures of salaries and benefits.

With the cost of living drastically increasing, public schools have adapted by implementing cost-of-living adjustments. Inflation is also causing the cost of health care to rise, in turn increasing the cost of health care benefits. While the state does cover some of the financial responsibilities, schools are feeling the effects. No other factor garnered higher than 16% of responses.

Transportation is being funded at about 10%. There is no funding in the formula for safety/security and [school resource officers]. There is no inflation factor in the formula. Gas and utilities are breaking us.

– Chief Financial Officer, Rockdale County School District

Healthcare

This year, the State Health Benefit Plan (SHBP) voted to increase employer contributions for state employees by 67% or $635 per member per month.[7] While the state covers the employer portion for teachers and leaders, school districts must cover the employer share for non-certified staff—bus drivers and monitors, paraprofessionals, etc. Covering the employer share for these non-certified positions can become a significant issue for schools without additional state money.

How many non-certified positions does your district employ that are eligible for the State Health Benefit Plan (SHBP)?

Schools in the 94 districts and state-authorized charter schools surveyed employ 43,770 non-certified employees. If each of these positions were required to absorb the SHBP increases, it would account for an additional $28 million every month.

Without additional state funding to address the SHBP increases for non-certified school employees, what actions will your district take to meet the higher costs (e.g., layoffs, reassigning funding from other areas of the school)?

When asked how the budget would incorporate the health insurance increases, school leaders most often answered that positions would have to be cut. Forty-four percent of those who responded shared that they would be forced to reduce their workforce by layoffs, not filling positions opened by those who retired, or in some other manner. Five districts mentioned raising class sizes specifically. The percentage of districts using layoffs is likely higher when you consider that 38% noted that they would reassign funding from other areas—a process that would in many cases would require firing staff. Additionally, five percent intend to employ contractors for current positions, meaning that state employees will be let go in favor of outsourcing.

One of the biggest challenges we have is finding staff. Certified teacher applicants are scarce, and more and more we are hiring teachers with no education degree on a provisional basis because we have no other options. We struggle to keep support staff like paraprofessionals and bus drivers because pay for those positions is low. We have resorted to using staffing agencies to hire paraprofessionals because we can do so much cheaper than making those people our employees (no costs for benefits… a para that takes insurance doubles the cost to us for that position), but we struggle to keep them because of lack of pay and benefits. Effectively educating students, especially in grades K-5, takes quality, trained staff at a ratio that allows us to work effectively with kids that need it. Our funding levels, both state and locally through property taxes, make that challenging to accomplish.

– Charlton County Schools

Additionally, 27% of those surveyed mentioned using local funding by either a growing tax digest or raising the property tax millage rate. Three respondents said that they would have to eliminate existing programs, and one district said they would apply for funding through grants.

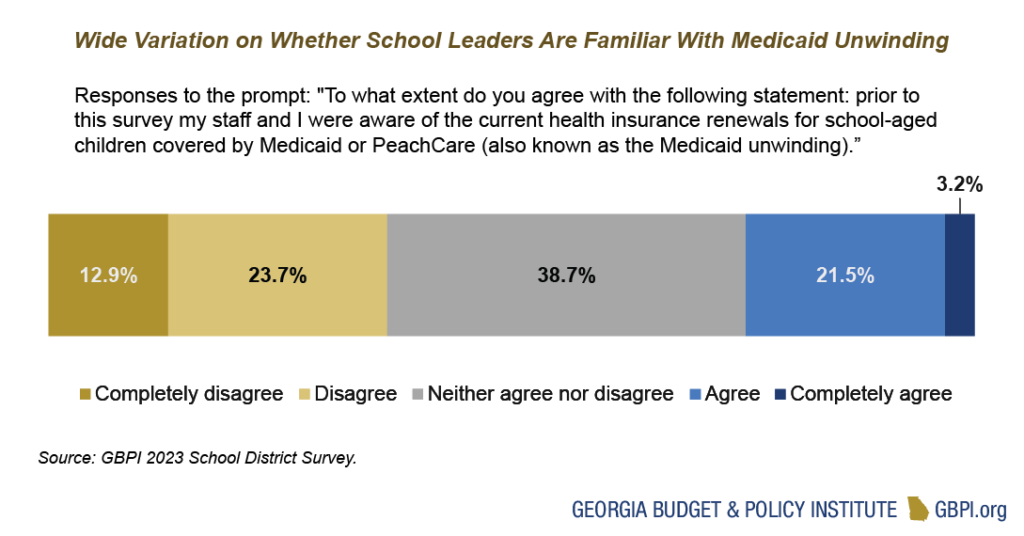

To what extent do you agree with the following statement: prior to this survey my staff and I were aware of the current health insurance renewals for school-aged children covered by Medicaid or PeachCare (also known as the Medicaid Unwinding).

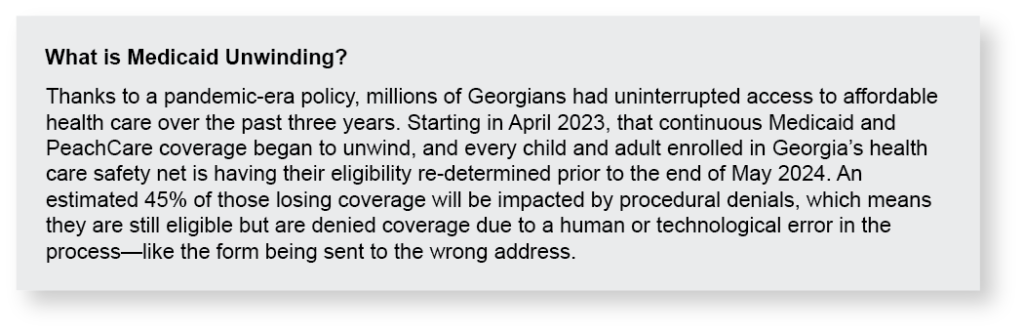

The rise in SHBP rates is not the only way changing health coverage can affect education. Thousands of Georgia children are expected to lose Medicaid/PeachCare coverage via a process called Medicaid Unwinding.

At the time of the survey, only a quarter (24.7%) of those surveyed were familiar with Medicaid Unwinding. A breakdown of the responses is in the bar chart below.

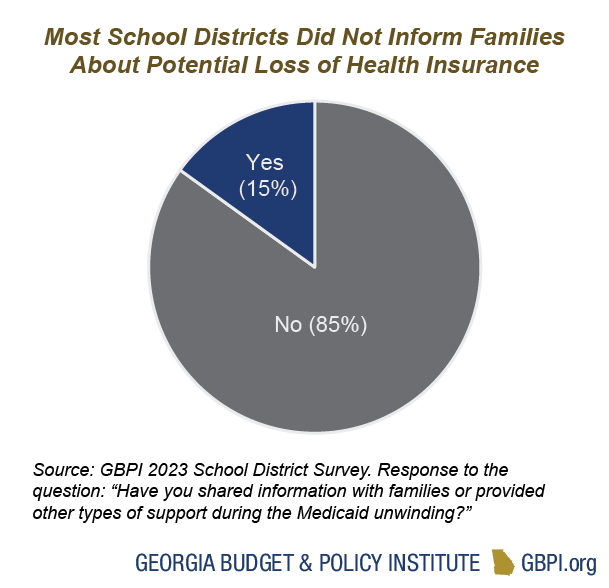

Have you shared information with families or provided other types of support during the Medicaid Unwinding?

Perhaps the low visibility of this impactful process explains why only 15% of district leaders reported sharing information with families or providing other support. Schools can help families avoid losing health care coverage by acting as messengers throughout Medicaid Unwinding. Those district leaders who shared information reported directing staff members or social workers to contact families, as well as using social media or sending email alerts.

Students in Poverty

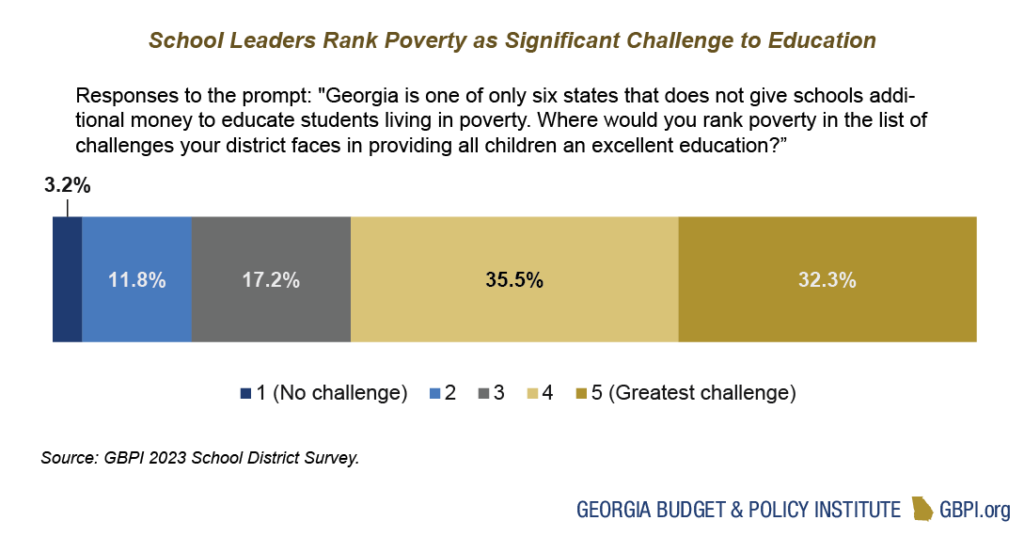

Georgia is one of only six states that does not give schools additional money to educate students living in poverty. Where would you rank poverty in the list of challenges your district faces in providing all children an excellent education?

New data from the U.S. Census reveals that child poverty more than doubled in 2022 compared to the year prior.[8] When asked to provide the level of challenge educating students in poverty schools faced, 68% of school leaders ranked it a 4 or 5—5 representing the most challenging. Only three percent of respondents reported that educating students in poverty posed no challenge at all.

Generations of white supremacist policies have ensured that wealth and race are connected in Georgia. Therefore, it is impossible to talk about generational poverty without understanding racism. The cumulative effect of slavery, Jim Crow legislation, school and housing segregation, explicit and implicit bias and more created and cemented the persistent poverty in Black and Brown communities in the U.S. Even once racist policies are removed, wealth can be determined well before a child enters the workforce. School leaders who have prioritized support for students experiencing poverty are, knowingly or not, advancing racial justice.

If lawmakers did create a grant for schools specifically to educate students living in poverty, how would your district use the funds to support these students?

In addition to being asked to rank the challenge, the survey asked leaders what they would do if granted funds specifically for educating students in poverty. The most common responses dealt with academic interventions: tutoring, materials and lowering class sizes (mentioned in 52 responses). Next, respondents mentioned basic needs such as transportation, food and clothing (23 responses). Eight responses highlighted the need for mental health and social-emotional supports specifically.

Anyone who has any involvement in K-12 education knows that it takes more resources to educate low income students on the whole. I know we talked about this toward the end of Governor Deal’s term, but it never got past the Commission stage.

– Georgia Cyber Academy

Policy Implications

Feedback from the survey underscores the real impact of increased costs on Georgia’s public education system. Failure to account for the effect of poverty, health insurance changes or something as simple as the cost of gas for buses leaves schools scrambling to do more with less. The following are three straightforward steps that state lawmakers can take to address concerns raised in the 2023 GBPI School District Survey:

Create an Opportunity Weight in the school funding formula to support students in poverty. Lawmakers failed to advance a bill to create such a grant (HB 3) last session.[9] The responses from this survey show school systems forced into providing basic needs for families well beyond the traditional understanding of “schooling.” Those districts without robust local property taxes either fail to offer these services or must pull from other areas of the school budget. The state must support all schools by recognizing this growing need which disparately impacts people of color. Notably, an Opportunity Weight remains crucial to helping Georgia overcome a history of racial discrimination.[10]

Increase state investment in pupil transportation. School bus driver and monitor “shortages” are nothing more than a shortage of state investment in this legally required school program.[11] With stronger pay and adequate school bus replacement funds, lawmakers can lower travel times and ensure safe passage for hundreds of thousands of children. In addition, increasing pay for school bus drivers is a matter of racial equity, with Georgia’s non-certified public school employees in transportation more likely to be people of color.[12]

Support schools with employer portion of non-certified employee health insurance. With the increase in state employee health insurance, school budget writers are in a bind.[13] Without significant money from the state, school leaders will be forced to lay off staff. The result will be larger class sizes and/or removal of school programs. The state must step in to avoid lowering the quality of education for Georgia’s students.

Acknowledgements

The Georgia Budget & Policy Institute would like to thank the school districts who participated in this survey and were essential in collecting valuable insights on the status of Georgia’s schools. The thoughtful responses and honest feedback collected in the survey are greatly appreciated and will be used to advocate for policies that best support students across the state. District leaders, school leaders and educators have our respect and gratitude for the work they do each day to serve Georgia’s students and their continued commitment to public education.

Appendix: Methodology

Dr. Stephen Owens developed the survey questions. Jariel Davis, who was a Southern Education Leadership Initiative fellow placed at GBPI during the summer of 2023, distributed the survey, conducted follow-up outreach, supported respondents with any questions and analyzed the results.

The survey was sent via email to every superintendent in the state. A link to the online survey was included along with a PDF version of the same survey. Ms. Davis subsequently contacted superintendents and other central office staff via phone and email to request their participation over a period of six weeks. The survey was available between June and July of 2023. Participation was voluntary. PDF submissions were manually entered by Ms. Davis into the online survey link, and GBPI exported a spreadsheet with all survey responses.

Endnotes

[1] Georgia Department of Education. School system revenues: Fiscal year 2022 financial data collection system. https://financeweb.doe.k12.ga.us/FinancialPublicWeb/ReportsMenuPublic.aspx

[2] Seider, J. J. (2023, May 8). Georgia’s aging school buses, bus driver shortage lead to missed classes, meals and safety issues. State Affairs. https://stateaffairs.com/georgia/education/georgia-school-bus-driver-shortages-aging-buses-pt1/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Owens, S. (2023). Georgia education budget primer for state fiscal year 2024. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgia-education-budget-primer-for-state-fiscal-year-2024/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Bartash, J. (2023, September 12). Inflation is set for a big increase, CPI to show. Here’s why. Market Watch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/inflation-is-set-for-a-big-increase-cpi-to-show-heres-why-9e6fe266

[7] Amy, J. (2023, February 1). Georgia House aims to ease health insurance costs on schools. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/georgia-state-government-subsidies-education-taxes-92100dce9f0e61fc94f901f0d6410c93

[8] Peck, E. (2023, September 12). Child poverty more than doubled last year. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2023/09/12/poverty-rate-child-benefits-expire

[9] House Bill 3 (as introduced December 21, 2022). https://legiscan.com/GA/bill/HB3/2023

[10] Owens, S. (2023, January 26). State of education funding (2023): Opportunity is knocking. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/state-of-education-funding-2023-opportunity-is-knocking/; Owens, S. (2019, October 10). Education in Georgia’s Black Belt: Policy solutions to help overcome a history of exclusion. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/education-in-georgias-black-belt/

[11] Owens, S. (2022, January 6). State of Education funding (2022). Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/state-of-education-funding-2022/

[12] Owens, S. (2021, October 7). America’s bus-driver ‘shortage’ isn’t new: It’s due to years of underfunding, and it’s putting kids at risk. Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/bus-driver-shortage-due-to-underfunding-schools-public-education-america-2021-10; Sieder, J. L. (2023, May 8). Georgia’s struggling school bus system: Finding funds and drivers. State Affairs. https://stateaffairs.com/georgia/education/georgia-school-bus-driver-shortages-aging-buses-pt2/

[13] Owens, S. (2023, June 27). Georgia education budget primer for state fiscal year 2024. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/georgia-education-budget-primer-for-state-fiscal-year-2024/