The state of Georgia withheld $9 billion from public schools over the last fifteen years. This report offers five policy options that would increase the fairness of Georgia’s education funding and begin to make school districts whole.

Sixty-one percent of Georgia students come from economically disadvantaged homes, living at or near the poverty line[1], and family income is closely linked to educational attainment. Students who live in poverty are more likely to face the challenges of housing instability, lack of access to high-quality out-of-school resources, and toxic stress, which all impede school success.[2] Fixing school funding shortcomings can play a major role in improving student achievement, especially for children who live in poverty.[3]

Conversely, Georgia ranks No. 37 in the nation in education funding in the United States, even when regional cost differences are considered.[4] Deep recession-era funding reductions — also called austerity cuts — to education spending starved the state’s schools of more than $9 billion from 2003 to 2018.[5] When the state decreases funding for education, local taxes are used to cover the gaps to finance school operations. School districts with a smaller tax base are then disproportionately affected by spending cuts. Schools with less revenue responded to the state’s budget cuts by furloughing teachers, increasing class sizes and eliminating some electives altogether.

The state budgeted enough this year to fully fund the state’s K-12 education formula for the first time since 2002. The end of years of austerity cuts provides Georgia’s policymakers an opportunity to fix funding inequities among school districts to bolster those that contain the populations that face the most systematic barriers.

Georgia pays for schools through the Quality Basic Education Act that was first implemented in 1987. This report offers five policy options to move beyond a basic education and increase the equity of Georgia’s education funding so that all students have the best chance for academic success.

- Track spending at the school level

- Rethink early intervention and remediation funding

- Restore bus transportation funding

- Reestablish equalization grants to 75 percent

- Complete overhaul of Georgia’s education funding mechanism

Each option requires additional spending above what the state currently allocates, but it is important to view them as investments in Georgia’s future workforce. Every dollar spent on ensuring all students have equally high levels of performance regardless of race, ethnicity, zip code, or economic status saves an estimated $2.60 due to increased tax revenues and decreased spending on social programs, according to a RAND Corp. study.[6] Significant public commitment to school funding might even pay for itself in future economic growth, according to a Center for American Progress study.[7] A stronger and more equitable commitment to K-12 public schools is a sound strategy to help Georgia’s children, their communities, and the state’s economy.

Five Policy Options to Fix Georgia’s K-12 Funding

Georgia’s opportunities to tackle funding inequities come at costs that range widely, but each provide some measure of new support for students that Georgia policymakers traditionally leave underserved.

1) Track Spending at the School Level

Cost: $10 million

Many observers assume individual schools set their own budget. However, school districts and local administrators make most funding decisions. Georgia’s Constitution grants authority to school boards to establish and maintain schools. Funding from the federal, state, and local level is distributed to the school districts overseen by those boards that determine how to use the money in those schools. These roles are important to understand to determine the fair use of education dollars in the state.

Georgia policies aim to ensure education funding is equitable among its 181 school districts. One strategy to accomplish that goal is through equalization grants that allocate more state money to school districts that lack enough taxable property wealth to provide an adequate education. Sparsity grants are another mechanism used to give assistance to districts that serve smaller numbers of students. These school systems are often financially inefficient compared to larger districts because they’re less able to carry fixed costs associated with services that state law requires. Each traditional school district must provide transportation even if the bus is not full, for example.

These existing strategies have varying degrees of success for equalizing funding among local districts. The underlying assumption is that local officials will fairly distribute money to the individual schools. Like many states, Georgia does not require detailed budgets at the school level. The result is severe inequalities among schools in the same district, according to the Brookings Institute.[8] Schools that serve higher concentrations of students who live in poverty are more likely to receive less funding than schools in higher income communities.[9]

Gov. Nathan Deal signed House Bill 139 in 2017 to require school districts to provide certain school-level revenue and expenditure data. The law requires disclosure in five areas of school spending:

- Cost of all materials, equipment, and other non-staff support

- Salary and benefit expenditures for all staff

- Annual cost of all professional development, including training, materials, and tuition provided for instructional staff

- Total cost of facility maintenance and small capital projects

- Spending for new construction or major renovation, based on the school system facility plan

HB 139 did not include any funding to enact changes to Georgia’s education budgeting practices. The language of this bill also discourages comparisons. Instead of making it easier to compare school finances, the legislation makes apples-to-apples financial reviews impossible.

The first and third reporting requirements include duplicate costs, for example. In one reporting area the school is asked to show the cost of all materials, and in another the school is asked to include again any such materials used for professional development.

The law also requires a report on the dollar amount spent per student enrolled at each school and district. This per-pupil figure is the total dollar amount spent by schools divided by the number of students served. This number’s use for equity or efficiency comparisons is undermined by the calculation itself. Students with disabilities are guaranteed more federal and state education funding, for example. A school with a higher percentage of students with disabilities will also have an unfairly inflated per-pupil spending level. A true study of inefficiency or inequity weighs the many inputs that contribute to the cost of education, such as regional differences and student demographics. Simply dividing total dollars by student head count is an inherently flawed method to measure equity.[10]

Georgia’s schools and districts need the ability to track spending at the school level. This one-time expenditure would provide support through changes to the state’s chart of accounts as well as professional development for school finance staffers. Only then can parents, school leaders, and state policymakers ensure equitable funding for Georgia’s students are specific to a local school. A better measuring stick paired with improved reporting would not guarantee fairer spending among all student groups, but it would make spending easier to monitor and address.

2) Rethink Early Intervention and Remediation Funding

Cost: $106 million

If policymakers are committed to equitable funding, one established part of the state’s education finance mechanism is worth reviewing and enhancing. Students who perform below the level typical of their grade can be eligible to participate in the Early Intervention Program (EIP) for kindergarten through fifth grade, or the Remedial Education Program (REP), for sixth through twelfth grade. Both programs earn schools additional funds from the state based on grade level.

The guidelines for EIP call for increased funding for some students with the rationale: “Children start school at a designated chronological age, but differ greatly in their individual development and experience base.”[11] Students in the program get access to more attention through smaller sized classes or an additional teacher in their general education class.[12] Individual school districts are allowed flexibility to choose the best model to serve these students.[13] The benefits of smaller class sizes are abundantly clear, especially for low-income students, research shows.[14]

Georgia’s funding system weights programs and grades through complex calculations. More money is allotted for the portion of the school day a student spends in early intervention or remedial program classes. The table below shows how general education programs are weighted, as well as EIP and REP.

| Program | Weight | |

| General Education | Remedial Education | |

| Kindergarten | 1.65 | 2.04 |

| Primary Grades (1-3) | 1.29 | 1.79 |

| Upper Elementary (4-5) | 1.04 | 1.79 |

| Middle School (6-8) | 1.13 | 1.31 |

| High School (9-12) | 1 | 1.31 |

Note: The Georgia General Assembly set the basic unit cost for the 2019 budget at $2,620.77. Earnings can be calculated by multiplying this amount by the corresponding program weight.

Under this system, if the state of Georgia allots $3,000 for general education high school (at a weight of 1), then a student in a full day of kindergarten would be allotted $4,950 (the base amount multiplied by 1.65). If Georgia funded early intervention and remedial programs at a weight of 2 for first through twelfth grade while keeping the weight 2.04 for kindergarten, $106 million in new investment can assist students who are traditionally underserved by the state.

There are other considerations that are worth mentioning with EIP and REP. Schools are now required to cap remedial program enrollment at 25 percent of the student body unless more than 50 percent of the student population is eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch, which triggers a 35 percent cap. Funding schools this way withholds money from the neediest schools in the state under the guise of fairness. Efforts to improve funding equity ought to include lifting this cap for the highest-poverty schools.

A redesign of the programs ought to allow the percentage of eligible students match the percentage of students living in poverty based on federal lunch programs, or other designations.[15] That change raises the cost beyond the estimated $106 million price tag.

3) Restore Bus Transportation Funding

Cost: $312 million

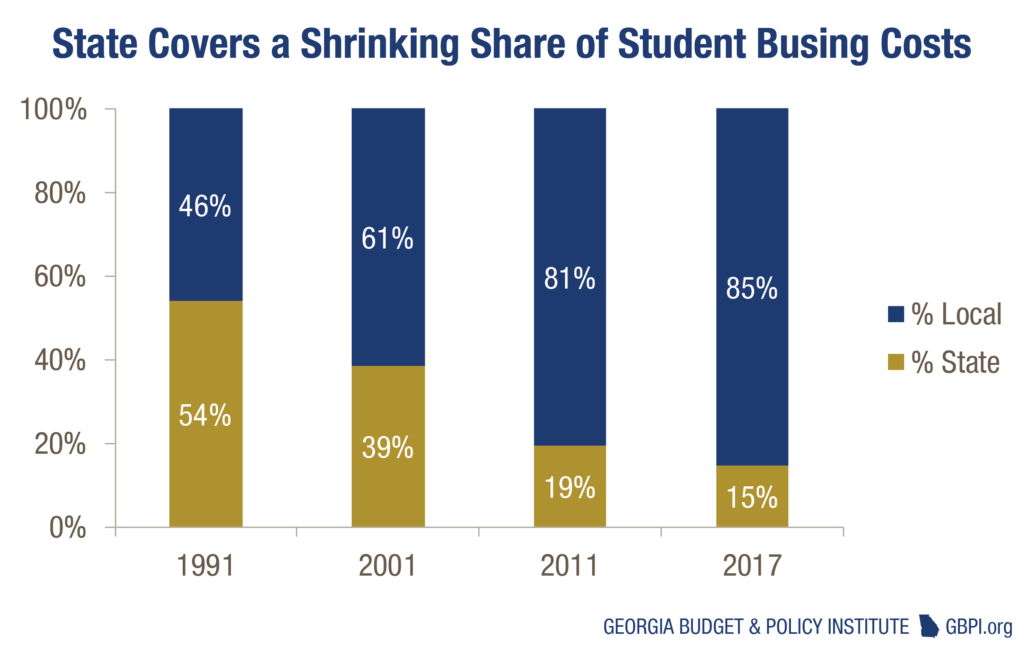

State policymakers shifted the burden to pay for non-teaching staff health insurance from the state to local school districts during the recession that ended in 2009.[16] This shift decreased state education spending, leaving districts to cover the cost. This change has continued a trend of the state lowering its share of student transportation spending since 1991, when it covered 54 percent of the cost.

School districts saddled with health insurance and higher transportation costs once carried by the state are tapping money once used for other school needs. Rising fuel prices and the need for more drivers as enrollment grows also eat at local budgets. Meanwhile, state lawmakers declined to come up with money to replace the state’s aging bus fleet. In 2018, 3,638 buses at least 15 years old or older belonged to Georgia schools. This amount represents nearly a quarter of all school buses driven daily on Georgia’s roads. Older buses are more likely to break down and lack advanced safety features.[17] The state’s 2019 budget allocates $16.3 million in bonds for school bus replacement, which equates to just under 176 buses. It is not enough to replace even 5 percent of the buses 15 years and older.[18]

Safe, reliable transportation to and from school ought to be provided to all of Georgia’s public-school students, regardless of the wealth of their community. If the state paid half the cost to bus students, districts could use the savings to reduce class sizes, offer support services for the community, or on other initiatives to improve student learning. Georgia law should also be changed as to require all public schools to provide transportation to and from the schoolhouse.[19] State lawmakers will need to budget $312 million more to resume prior support for student transportation.

4) Reestablish Equalization Grants at 75 Percent

Cost: $516 million

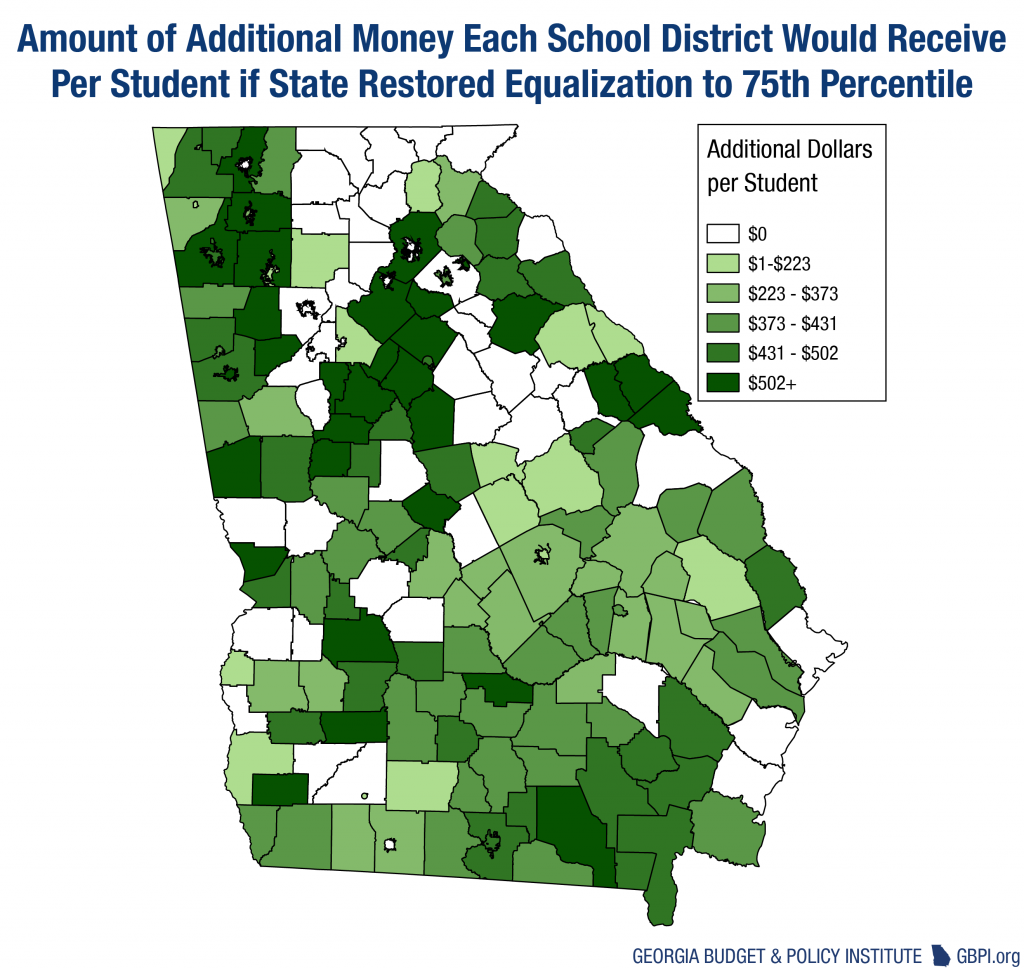

Local taxes generate more than 40 percent of the funding for K-12 education in Georgia.[20] The value of taxable property varies greatly across the state. Cities and counties with robust local economies enjoy larger tax bases compared to struggling communities. Low-wealth school districts face greater challenges raising money to provide students an adequate education. Georgia’s school funding formula aims to take these disparities into account and offers grants to low-wealth districts to equalize funding across the state. School systems can spend these equalization grants as they see fit.

Equalization grants are calculated by ranking each school district by the property tax wealth per student. The average tax valuation is determined after removing the top and bottom 5 percent of districts and the ones below that threshold are provided equalization dollars.[21] This method to determine equalization was only put in place in 2012 after years of state lawmakers underfunding the grant.[22] Georgia’s current formula for financing education was first implemented in 1987. For the first thirteen years of the formula, the state equalized districts to the 90th percentile, meaning that all districts with property value below the top 10 percent received more money in pursuit of equity. Lawmakers lowered the threshold in 2000 to the 75th percentile during an economic downturn. In the throes of the Great Recession lawmakers lowered the threshold again to an average-value calculation.[23]

Equalizing funding to the average district’s property tax wealth and removing the top and bottom five percent of districts combined to reduce state payments to school districts by billions of dollars since the 2012 change. Moving from the 75 percent threshold to the current equalization caused districts to receive $340 million less in the 2013 state budget alone.[24] Restoring a 75th percentile benchmark for funding can give districts resources tied to the level of community need.

Consider Chattahoochee County schools. Restore the equalization grant to the 75th percentile and Chattahoochee County School District receives $373,000 more in unrestricted money.[25] That $464 per student, or full-time equivalent, represents a 6 percent funding increase for the school system every year. This money can help make up the difference academically between students in poorer districts and the rest of the state. The state can dramatically increase the opportunity for students like the ones in Chattahoochee County public schools with this one change in Georgia’s education financing.

Consider Chattahoochee County schools. Restore the equalization grant to the 75th percentile and Chattahoochee County School District receives $373,000 more in unrestricted money.[25] That $464 per student, or full-time equivalent, represents a 6 percent funding increase for the school system every year. This money can help make up the difference academically between students in poorer districts and the rest of the state. The state can dramatically increase the opportunity for students like the ones in Chattahoochee County public schools with this one change in Georgia’s education financing.

5) Complete Overhaul of Georgia’s Education Funding System

Cost: To be determined by analysis of true cost of educating a student to state standards

The uncomfortable truth behind every school funding discussion in Georgia is that there is no hard evidence that shows the true cost to educate a child. A governor-appointed commission in 2015 attempted to update the funding formula and eventually sidestepped the issue in favor of redistributing the existing pool of money.[26] Instead the state continues to finance schools based on a formula created at a time when few Georgians owned a personal computer. More elements of schooling have changed than remained the same in the past three decades. The biggest changes are the requirements the state now imposes on students and the demographics of those students.

First, as a part of the legislation that established the current funding structure, the state created a series of curriculum standards (the Quality Core Curriculum, or QCCs) in the 1985 formula designed to outline what students ought to know by the end of each grade.[27] However, 2001’s No Child Left Behind Act prompted an audit of the Quality Core Curriculum that found it, “not only lacked depth and could not be covered in a reasonable amount of time; it did not even meet national standards.”[28] State education policymakers created the Georgia Performance Standards after evaluating high-achieving states and countries. The Georgia Standards of Excellence later followed.[29] Students now enrolled in Georgia’s public schools are held to a more rigorous set of standards than students under the original funding formula.

Second, not every student arrives in kindergarten at the same educational level. One positive result of Gov. Deal’s Education Reform Commission is the recognition that students living in poverty should get more state dollars for their education. The early intervention programs are attempts to target help for some of these students, but program eligibility caps assume the same percentage of students in every district. Housing segregation based on race and income in the state ensures some districts educate a much larger percentage of traditionally underserved students than others.[30]

Georgia policymakers continue to expect students to compete globally without the promise of adequate education funding. State lawmakers can better prepare these students for that competition if they determine the true cost of education. Advanced analyses consider the impact of inputs such as language proficiency, poverty, student migration, fiscal capacity, and state region. Without a credible cost analysis, state leaders are left to debate education spending levels that may not correlate to student performance.

Conclusion

Seventy-two percent of Georgians surveyed in 2018 said they would support spending more on schools if a study says it is necessary to meet student education needs.[31] Traditional public schooling is accepted as an economic common good, so state policymakers can be assured that any additional money spent on investing in equity will reap a healthy return. Investing more in public schools is a proven way to decrease the need for welfare programs in future years. Students who graduate high school are less likely to encounter the criminal justice system or need food assistance from the state.[32] Financial equity offers the dual benefit of helping Georgia’s students today and saving the state money in the long run. Public education presents benefits above and beyond the purely financial as well. A robust education system has the opportunity to increase participation in other civic institutions, cultivate critical thinking, and foster creativity. State policymakers can offer these benefits to more Georgians through policies such as the ones listed in this report. These options offer possibilities with a wide price range and each can serve to push the state’s public schools to better serve all Georgians. After years of withholding public dollars from public schools, it is time for the state to restore funding to those communities that lost the most.

Endnotes

[1] Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. (2018). Retrieved from: https://gbpi.org/2018/new-poll-shows-overwhelming-support-for-gbpi-people-first-plan/

[2] Suggs, C. (2018). Tackle poverty’s effects to improve school performance. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. Retrieved from: https://cdn.gbpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Tackle-Poverty-in-Schools.pdf

[3] Lafortune, J., Rothstein, J., & Whitmore Schanzenbach, D. (2016). Can school finance reforms improve student achievement?; Jackson, C. K., Johnson, R. C., & Persico, C. (2015). The effects of school spending on educational and economic outcomes: Evidence from school finance reforms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(1), 157-218.

[4] Baker, B., Farrie, D. Johnson, M., Luhm, T., and Sciarra, D. (2017). Is school funding fair? A national report card. Education Law Center. Retrieved from: http://www.edlawcenter.org/assets/files/pdfs/publications/ National_Report_Card_2017.pdf

[5] Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. (2018). Georgia Budget Primer 2019. Retrieved from: https://cdn.gbpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Georgia-Budget-Primer-2019.pdf

[6] Vernez, G., Krop, R. A., & Rydell, C. P. (1999). Closing the Education Gap: Benefits and Costs. RAND, 1700 Main Street, PO Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138.

[7] Lynch, R. G., & Oakford, P. (2014). The Economic Benefits of Closing Educational Achievement Gaps: Promoting Growth and Strengthening the Nation by Improving the Educational Outcomes of Children of Color. Center for American Progress.

[8] Roza, M., Hill, P. T., Sclafani, S., & Speakman, S. (2004). How within-district spending inequities help some schools to fail. Brookings papers on education policy, (7), 201-227.; Rubenstein, R. (1998). Resource equity in the Chicago Public Schools: A school-level approach. Journal of Education Finance, 23(4), 468-489.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Baker, B. D., & Weber, M. (2016). Deconstructing the Myth of American Public Schooling Inefficiency. Albert Shanker Institute.

[11] Georgia Department of Education. (2018). Early Intervention Program (EIP) Guidance 2018-2019. Retrieved from: http://www.gadoe.org/Curriculum-Instruction-and-Assessment/Curriculum-and-Instruction/Documents/EIP/2018-2019-EIP-Guidance.pdf

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid. See the EIP Guidance document for a list of potential models.

[14] Nye, B., Hedges, L. V., & Konstantopoulos, S. (2000). The effects of small classes on academic achievement: The results of the Tennessee class size experiment. American Educational Research Journal, 37(1), 123-151.

[15] See the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement website for direct certification guidelines.

[16] Suggs, C. (2018). Overview: 2019 Fiscal Year Budget for K-12 Education. Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. Retrieved from: https://gbpi.org/2018/overview-2019-georgia-budget-k-12-education/

[17] Suggs, C. (2018). Shrinking State Funds Trigger Student Bus Safety Concerns. Georgia Budget & Policy Institute. Retrieved from: https://gbpi.org/2018/shrinking-state-funds-trigger-student-bus-safety-concerns/

[18] According to the Georgia Department of Education, the cost of a basic bus is $77,220. A basic bus has no extras including air conditioning. The average actual bus price paid by Georgia districts in fiscal year 2017 was $92,365. (Georgia Department of Education. (2017) Pupil Transportation Division Legislative Report. Atlanta, GA: Same.)

[19] In Georgia, public charter schools are not required to provide student transportation. They are, however, offered funding for transportation if they provide it – O.C.G.A. § 20-2-2068.

[20] Georgia Department of Education. (2018). Local, State, and Federal Revenue Report. Retrieved from: https://app3.doe.k12.ga.us/ows-bin/owa/fin_pack_revenue.display_proc

[21] O.C.G.A. § 20-2-165.

[22] Johnson, C.D. (2012). Bill Analysis: House Bill 824. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

[23] Governor’s Office of Student Achievement. (2015). Equalization. Five Mill Share Equal Sparsity Review. Retrieved from: https://gov.georgia.gov/sites/gov.georgia.gov/files/related_files/site_page/Five%20Mill%20Share%20Equal%20Sparsity%20Review.pdf

[24] Johnson, C.D. (2012). Bill Analysis: House Bill 824. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

[25] Based on GBPI analysis of current local revenues.

[26] Tygami, T. (2015, June 11). Gov. Deal’s Education Reform Commission pushes back on school funding. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved from: https://www.ajc.com/news/local-education/gov-deal-education-reform-commission-pushes-back-school-funding/RDXH8ayKGXXu1epFJebYWI/

[27] Mitzell, J. (1999). The adoption of the Georgia quality core curriculum: A historical analysis of curriculum change. The University of Georgia.

[28] Department of Education. (2005). Georgia performance standards: Curriculum Frequently

Asked Questions. Atlanta, GA: State of Georgia. Retrieved from: http://www.georgiastandards.org/faqs.aspx

[29] Greer, L. (2013). Common Core Standards. Senate Research Office. Retrieved from: http://www.senate.ga.gov/sro/Documents/AtIssue/atissue_June13.pdf

[30] See ProPublica’s Miseducation report (https://projects.propublica.org/miseducation/) on racial inequality in Georgia and how it compares nationally.

[31] Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. (2018). Retrieved from: https://gbpi.org/2018/new-poll-shows-overwhelming-support-for-gbpi-people-first-plan/

[32] Vernez, G., Krop, R. A., & Rydell, C. P. (1999). Closing the Education Gap: Benefits and Costs. RAND, 1700 Main Street, PO Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138.