Update on Feb. 25, 2021: A new substitute for House Bill 60 (LC 49 0460S) lowers the cap on students participating to half of the original estimate, which would put the cost to the state at $224 million annually once fully implemented.

Key Takeaways

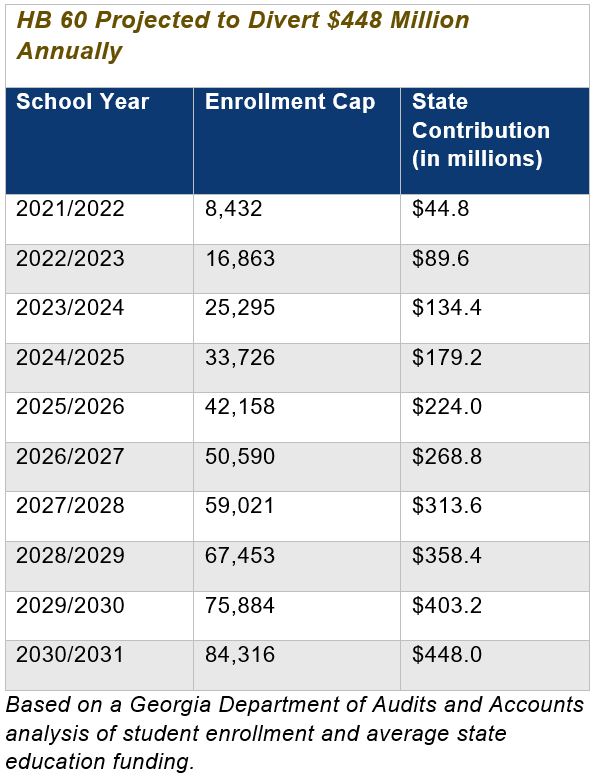

- House Bill 60 would cost the state $448 million annually once fully implemented

- This legislation targets school systems that, through local control, have decided to offer instruction virtually in response to the pandemic

- A recent state audit found noncompliance and risk for fraud in another of Georgia’s voucher programs

- State lawmakers concerned about Georgia’s children should reject HB 60 and consider legislation like HB 10 which provided additional funding for students who need it most

Introduction

Georgia lawmakers have filed a bill to divert hundreds of millions of public dollars to private schools. House Bill 60 would create an education savings account (ESA) for families to pay for private school tuition or qualified education expenses with funds from the state government. A previous review from the Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts found that, once fully implemented, a bill like HB 60 would cost the state $542.6 million annually.[1] This loss would come at the absolute worst time for public schools that are in the middle of a 19-year stretch of strict budget cuts where lawmakers have withheld $10.2 billion cumulatively from public education.[2]

HB 60 resembles legislation from previous sessions, where students in select groups are eligible for the voucher based on income or disability status. One major difference is the added provision that parents are eligible to receive the voucher if their local school is not open for “100 percent of instruction in person.”[3] Many schools have opted for virtual or hybrid instruction to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Targeting these school systems for decisions to protect students, teachers and the greater community puts school leaders in an impossible situation. Further, students who take advantage of this voucher would forfeit federal protections against discrimination, local funding and certain state assurances provided in public schools.

A recent state audit of the Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit, another voucher in Georgia, found that the $100 million “scholarship” program was vulnerable to fraud and waste due to weak transparency and accountability measures.[4] Georgia lawmakers should provide oversight to the existing vouchers before allocating additional funding to this unproven policy.

Cost

HB 60 caps participation in the voucher at 0.5 percent of the 2020/2021 school year enrollment—about 8,400 students.[5] The cap then increases by 0.5 percent for every subsequent year until topping off at 5 percent of the state’s public school enrollment. In its first year, the state would redirect a projected $45 million away from public schools, based on FY 2021 average per-full-time-equivalent student state spending of $5,313. Once fully implemented the school vouchers would cost the state a projected $448 million per year.

The Georgia Department of Audits reviewed similar legislation in 2019 and projected the cost at $543 million annually once fully implemented. The projection offered here is lower due to two factors: the lower enrollment in public schools compared to previous years and the reduction of state funding for public education. Both factors can be attributed to the effects of COVID-19, as early grade enrollments have dipped in the same year that the General Assembly passed a budget with cuts of $952 million to public schools. If public school enrollment increases and/or budget cuts are ended, then the projected cost to the state due to HB 60 will also increase. The actual cost of vouchers also depends on the participating child’s disability status. Those with an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), which ensure students necessary changes to the learning environment and are attached to increased funding for recipients’ education, would receive state funding higher than the average expenditure. However, any funding provided from the federal level would be forfeited.

Georgia’s Previous Missteps with Vouchers Make Case for Caution

Georgia currently has several avenues by which parents can pay private school tuition with state support. A recent performance audit by the Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts of the Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit showed that the program lacked transparency and legislative oversight. This program provides a tax credit to individuals and corporations that donate to pass-through organizations that then pay private school tuition for parents who apply. Among many issues, the audit highlights that there were inadequate controls in place to prevent individuals and corporations from receiving the tax break even if they have not earned it.[6] Further, the audit found that some voucher-granting organizations (called Student Scholarship Organizations or SSOs) regularly failed to report and/or verify legal requirements on how the vouchers were managed.[7] These structural flaws do not even address the fact that Georgians have no assurances of how students perform once their parents take advantage of this program, as these schools are not held accountable to state standards of excellence or tested to measure performance.

Vouchers in other states are tied to misuse of public funds as well. In Arizona, the state’s Attorney General audited their voucher system and found “persistent” misuse of funds year-after-year.[8] In one year alone, the state found fraudulent purchases totaling over $700,000 in charges for, among others, beauty supplies and athletic apparel. The academic research showing that vouchers are consistently associated with lower test scores for participating students calls into question the wisdom for promoting such a policy as well, especially when there is so much focus on the effects of the pandemic on student learning.[9]

Policy Considerations

Georgia has fully funded the state’s education funding formula only twice over the last 19 years. The pandemic has created new problems for schools and families trying to navigate education. Instead of supporting families in these difficult times, this policy would offer parents a prorated amount of the funding their children deserve for in a program with no evidence of success or fidelity. State lawmakers who are concerned about the quality of education should reject policies like vouchers that are associated with fraud and lack public transparency, and instead invest in communities that have been hit the hardest by COVID-19. Legislation like House Bill 10, which provides additional funding for students living in poverty, would offer new opportunities for every school in Georgia instead of singling out just the families who could use a voucher.[10]

End Notes

[1] Owens, S. (2019). Bills set stage to divert hundreds of millions of dollars from public to private schools. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/millions-diverted-to-private-schools/

[2] Owens, S. (2021). State of education funding (2021). Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/state-education-2021/

[3] House Bill 60. LC 49 0301 https://www.legis.ga.gov/legislation/58867

[4] Griffin, G. S., & McGuire, L. (2021). Qualified Education Expense Credit and Student Scholarship Program. Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts: Performance Audit Division. https://www.audits.ga.gov/PAO/20-12_QEEC-SSP.html

[5] Georgia Department of Education. Student enrollment by grade level (PK-12). https://oraapp.doe.k12.ga.us/ows-bin/owa/fte_pack_enrollgrade.entry_form (cited in: Owens, S. [2021]. State of education funding (2021). Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/state-education-2021/)

[6] Griffin, G. S., & McGuire, L. (2021). Qualified Education Expense Credit and Student Scholarship Program. Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts: Performance Audit Division. https://www.audits.ga.gov/PAO/20-12_QEEC-SSP.html

[7] Ibid. See Exhibit 11: Not All Relevant Legal Requirements Were Independently Verified and/or Reported to the State for Fiscal Year 2018.

[8] Perry, L. (2018). Arizona Department of Education: Empowerment Scholarship Accounts Program. Auditor General Report No. 16-107 24-Month Follow-up Report. https://www.azauditor.gov/system/tdf/16-107_24Mo_Followup.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=9096&force=0

[9] See: Abdulkadiroğlu, A., Pathak, P. A., & Walters, C. R. (2018). Free to choose: Can school choice reduce student achievement? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1), 175-206; Figlio, D., & Karbownik, K. (2016). Evaluation of Ohio’s EdChoice Scholarship Program: Selection, competition, and performance effects. Thomas B. Fordham Institute; Dynarski, M., Rui, N., Webber, A., & Gutmann, B. (2017). Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts after one year. NCEE 2017-4022. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance; Waddington, R. J., & Berends, M. (2018). Impact of the Indiana Choice Scholarship Program: Achievement effects for students in upper elementary and middle school. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(4), 783-808; Lubienski, C. A., & Lubienski, S. T. (2013). The public school advantage: Why public schools outperform private schools. University of Chicago Press.

[10] House Bill 10. LC 49 0262. https://www.legis.ga.gov/legislation/58795