Introduction

The only program in Georgia that is available to provide direct cash assistance to children in deep poverty—Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)—does little to reach families with the greatest needs. For those it can reach, it provides insufficient income support. In 1996, 254,000 children and families received direct cash aid, while today only 16,000 have access to TANF, reflecting a dramatic 93 percent decrease in caseload.[1] Only 5 out of every 100 families in poverty receive cash assistance through TANF.[2]

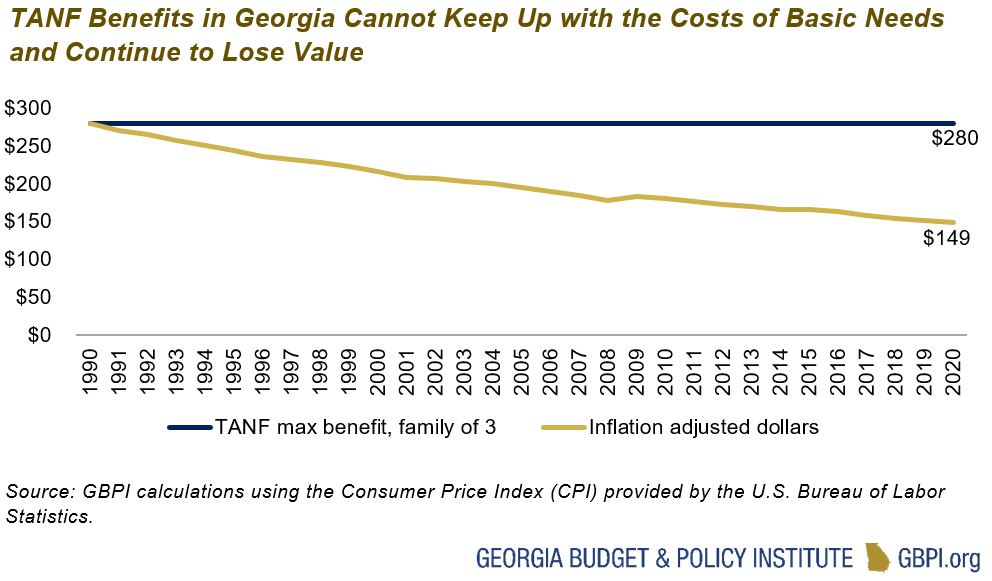

Georgia lawmakers have introduced House Bill 91, which would provide an overdue boost to families with children in deep poverty.[3] Georgia’s maximum benefit amount has remained unchanged since 1990, when the benefit was offered under Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC).[4] Insufficient benefits make the program unattractive for many families who would otherwise be eligible. The goal is not to make TANF pay for a family’s entire set of living expenses, nor is it intended to supplant the wages and benefits offered by living-wage jobs. But the benefit should recognize that all children in families facing poverty are deserving of a basic system of support when their parents or caregivers are unable to work through no fault of their own.

House Bill 91 would improve the reach and effectiveness of TANF cash assistance for eligible families with children by raising the maximum TANF cash assistance amount—which has been unchanged for 30 years at $280 for a family of three—by tying it to the deep federal poverty guidelines, which increase each year. The bill accomplishes this by adding a new section to the definition of cash assistance in O.C.G.A. § 49-4-181. The language states that the maximum cash assistance amount for a family shall be determined using a standard of need that is 50 percent of the federal poverty line, or “deep poverty.” The maximum benefit amount shall be 75 percent of the need standard for each family size.[5] The chart below illustrates the impact the change would have for TANF families if the current proposal is passed.

| Family size | Federal Poverty Level (monthly) |

New Need Standard as 50% of FPL

(deep poverty) |

New Benefit Amount as 75% of Need Standard | Current Benefit Amount |

| 1 | $1,063 | $532 | $399 | $155 |

| 2 | $1,437 | $718 | $539 | $235 |

| 3 | $1,810 | $905 | $679 | $280 |

| 4 | $2,183 | $1,092 | $819 | $330 |

| 5 | $2,557 | $1,278 | $959 | $378 |

| 6 | $2,930 | $1,465 | $1,099 | $410 |

| 7 | $3,303 | $1,652 | $1,239 | $444 |

| 8 | $3,677 | $1,838 | $1,379 | $470 |

Source: GBPI modeling of HB 91 changes for TANF families using the 2020 Federal Poverty Guidelines and Georgia’s current TANF benefit determination rules.

Cost

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is federally funded through a block grant to the state, and the largest share of that block grant currently funds line items in the child welfare budget. According to the Division of Child and Family Services (DCFS), state funds are used for only the very small population of two-parent households ($8,636 in state funds in fiscal year 2020).[6] Thus, changing the benefit amount will incur very little to no cost for the state.

Changing the cash benefit amount will require DFCS to spend more of the federal block grant on cash assistance. However, through the state’s appropriation process, Georgia lawmakers repeatedly choose to use TANF funds for things other than direct cash aid. In Fiscal Year 2021, Georgia will spend $315 million in federal TANF funds, and just 12 percent of that funding will be spent on basic cash assistance.

Budget writers have become dependent on using TANF in order to continue their cuts-only approach to balancing the state budget instead of raising new state revenues to adequately fund child welfare and deploying TANF funding for its intended purpose—cash aid to needy families.

Even as the state continues to choose not to raise revenues to adequately fund Georgia lawmakers do have the option to use surplus TANF funds to avoid transferring funds from other areas of the budget to accommodate this change. Georgia commonly has tens of millions of dollars in unused TANF funds at the end of each fiscal year, despite the critical need for families to draw down those funds for direct cash aid. The state’s unused TANF funds have grown from $42 million in 2015 to $88 million in 2019, according to the last financial report available.[7]

Policy Consideration: Cash Matters

In 2019, nearly 1.3 million Georgians lived below the poverty line, with 1 in 5 kids in poverty.[8] Children of color in Georgia are particularly impacted by poverty, with poverty rates three times higher for Black (28 percent) and Latinx (27 percent) children than for white (9 percent) and Asian (8 percent) children.[9] One in 10 Georgians are living in deep poverty, which is 50 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), or $905 per month for a family of three. Georgia’s deep poverty rates range from 26 percent in Clinch County to just 2.2 percent in Oconee County.[10]

TANF families must depend on meager benefits to contribute what they can to rent, oftentimes in substandard housing. As a result, they have higher rates of housing instability or, worse, homelessness.[11] Adequate housing is just one of the basics that families need cash assistance to cover. Although most TANF families are eligible for food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), these benefits often do not last the entire month. Further, SNAP and current TANF benefits combined would still not be enough to lift Georgia families with no other sources of income out of deep poverty.[12] TANF families also need to pay for diapers for infants, school-related expenses for school children, health expenses not covered by Medicaid and utility costs like electricity and water.

Income support, especially during an economic recession, improves children’s health, educational and economic outcomes while simultaneously reducing childhood poverty.[13] Even small amounts of cash assistance can make a difference. Among families in poverty, children under the age of 6 whose families receive a $3,000 annual increase in income earn 17 percent more as adults compared to children whose families did not receive an income boost.[14] Research also shows that targeted cash assistance could narrow the Black-white child poverty gap by up to 15 percent.[15] This finding suggests that by updating this outdated benefit structure, Georgia can achieve important gains for children in the short- and long-term.

Endnotes

[1] GBPI analysis of data retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

[2] Floyd, I. (2020, March). Policy brief: Cash assistance should reach millions more families. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/policy-brief-cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families

[3] House Bill 91. LC 33 8469. https://www.legis.ga.gov/legislation/58922

[4] The Urban Institute. (2020). Welfare rules databook. https://wrd.urban.org/wrd/Query/query.cfm

[5] House Bill 91. LC 33 8469. https://www.legis.ga.gov/legislation/58922

[6] Griffin, G. S. (2021). Fiscal Note LC 33 8456. Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts.

[7] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). TANF financial data – FY 2019. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/data/tanf-financial-data-fy-2019

[8] Hahn, H., Aron, L. Y., Lou, C., Pratt, E., & Okoli, A. (2017). Why does cash welfare depend on where you live. The Urban Institute.; Monnat, S. M. (2010). The color of welfare sanctioning: Exploring the individual and contextual roles of race on TANF case closures and benefit reductions. The Sociological Quarterly, 51(4), 678-707.; Rodgers Jr, H. R., & Tedin, K. L. (2006). State TANF spending: Predictors of state tax effort to support welfare reform. Review of Policy Research, 23(3), 745-759.; Parolin, Z. (2019). Temporary assistance for needy families and the Black–White child poverty gap in the United States. Socio-Economic Review.

[9] The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020, September). Child poverty rates by race in Georgia. KIDS COUNT Data Center.

[10] GBPI county-by-county analysis of deep poverty using data provided by the University of Michigan Poverty Solutions Project.

[11] Schwer, M. (2017). A systematic review of the primary material hardships of post-welfare reform TANF recipients. Social Work Master’s Clinical Research Papers. Retrieved from https://ir.stthomas.edu/ssw_mstrp/781

[12] Burnside, A. and Floyd, I. (2020). More States Raising TANF Benefits to Boost Families’ Economic Security. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/more-states-raising-tanf-benefits-to-boost-families-economic-security

[13] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2019). A roadmap to reducing child poverty. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25246/a-roadmap-to-reducing-child-poverty.

[14] Duncan, G., &. and K. Magnuson (2011). The long reach of early childhood poverty. Early Childhood Poverty. Retrieved from http://www.stanford.edu/group/scspi/_media/pdf/pathways/winter_2011/PathwaysWinter11_Duncan.pdf

[15] Parolin, Z. (2019). Temporary assistance for needy families and the Black–White child poverty gap in the United States. Socio-Economic Review. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/ser/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/ser/mwz025/5489411?redirectedFrom=fulltext