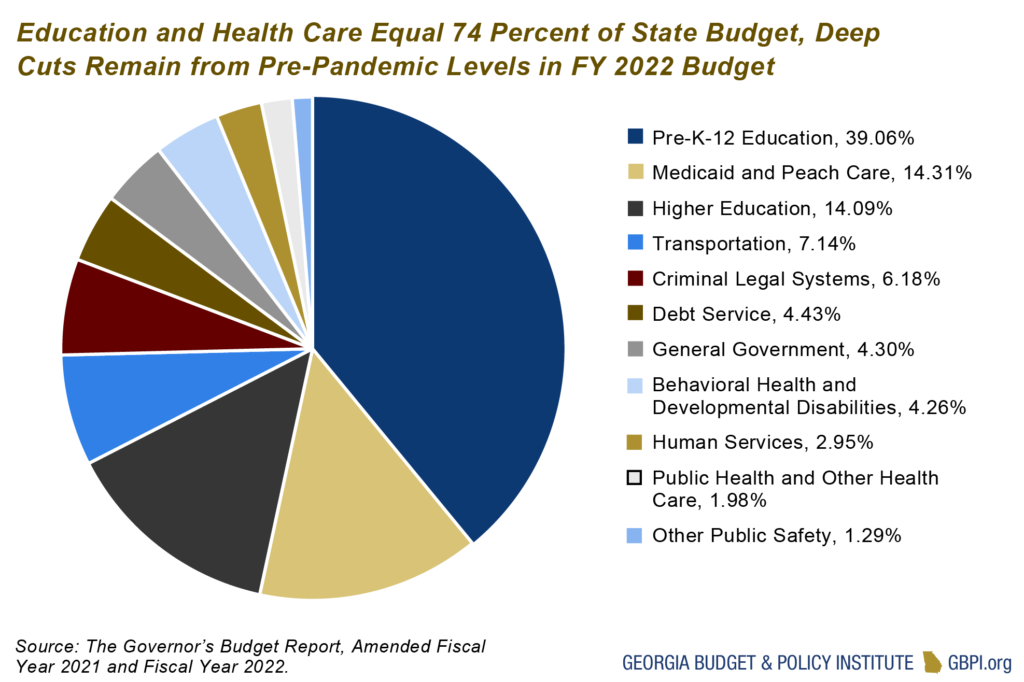

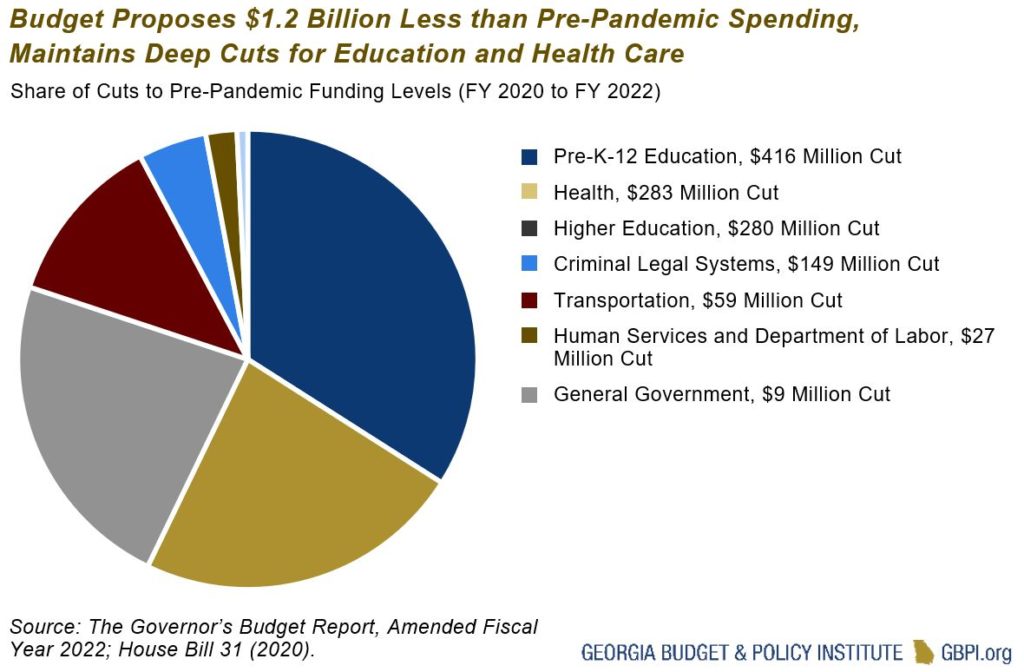

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which has plunged Georgia’s economy into recession and driven many of the state’s thinly staffed agencies to the brink, Gov. Brian P. Kemp’s proposed budget for Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 maintains $697 million in cuts to education, $283 million in cuts to health agencies and largely preserves the status quo of significantly underfunding core areas of state government.[1] Overall, the governor’s budget proposal would underfund state government in FY 2022 at a level approximately $1.2 billion below the state’s pre-pandemic budget (FY 2020).[2]

Each January the governor proposes two distinct budgets. The amended budget for FY 2021 adjusts spending levels for the current fiscal year that ends June 30 to reflect actual tax collections, enrollment growth and any spending changes over the course of the year. The full or “big” budget for FY 2022 lays out a new spending plan for the next fiscal year that starts on July 1, 2021.

After nearly a decade of efforts to restore billions in state budget cuts made as a result of the Great Recession of 2009, and in response to the recession induced by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Georgia implemented $2.2 billion in budget cuts with the passage of its FY 2021 spending plan, which took effect on July 1, 2020. Under the governor’s proposed FY 2022 budget, adjusted for inflation, the state would spend about $100 less per state resident—or 4 percent less—than it did in FY 2008, prior to the Great Recession.[3]

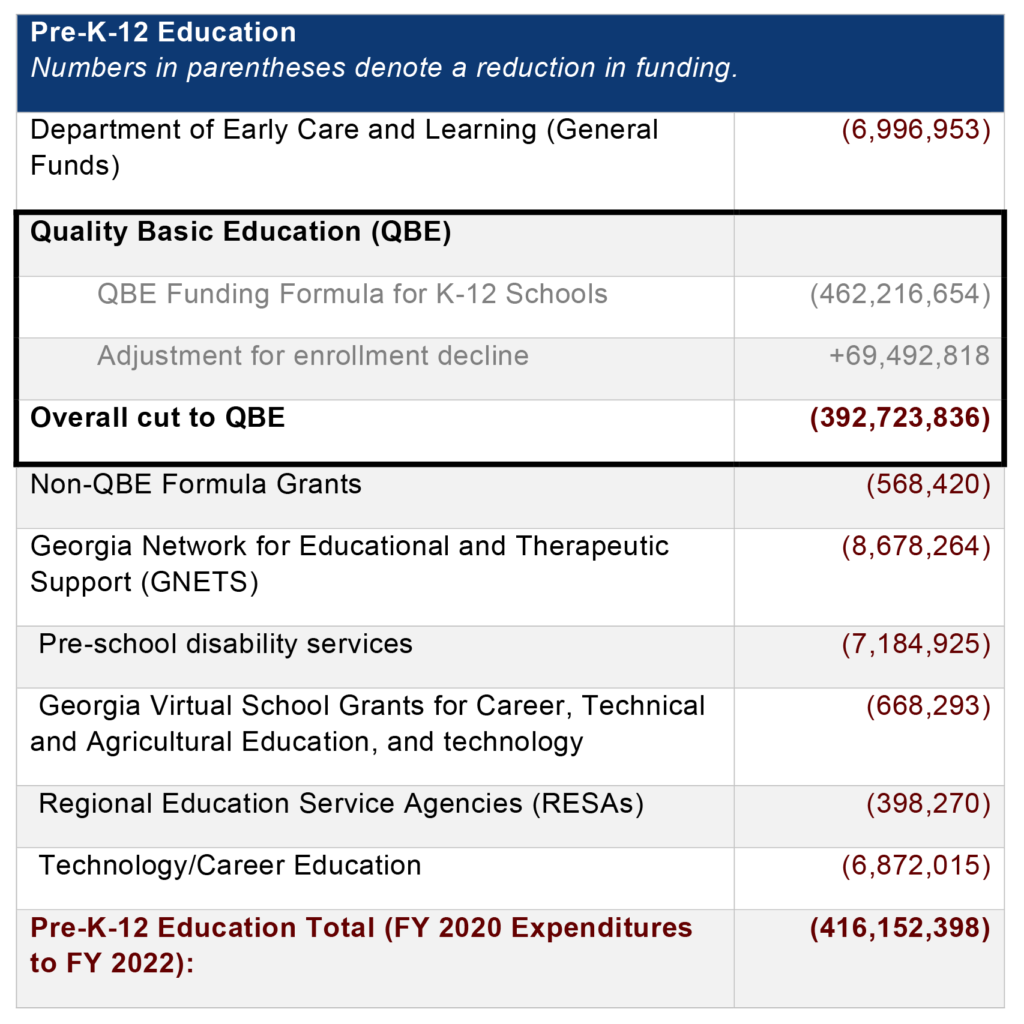

Of $1.2 billion in spending cuts from pre-pandemic levels proposed in the Governor’s budget for the next fiscal year, the lion’s share of reductions come at the expense of pre-K through 12th-grade public education. Gov. Kemp’s budget for FY 2022 proposes underfunding the state’s K-12 public education formula by $393 million, $14 million in cuts to early childhood education and pre-school and tens of millions in cuts to programs and grants operated by the Department of Education. Georgia’s higher education institutions would experience a $280 million reduction from FY 2020 spending levels, with the majority of cuts made to funds allocated for teaching.

Despite the continued demand for health care services and the obvious weakness of Georgia’s health care infrastructure underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic, the proposed FY 2022 would do almost nothing to restore significant cuts made to state health agencies. Under Gov. Kemp’s proposal, the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities would see cuts of $118 million extended; the Department of Public Health would receive $7 million less in total state funds; and the budget for departmental administration for Georgia’s Medicaid agency would be underfunded by $40 million below the level allocated for FY 2020. Other core agencies that have struggled to keep up with increased demand on staff and services would continue to experience similarly deep cuts, with the Department of Human Services receiving $26 million less in funding, $1 million cut from the Department of Labor and a combined $149 million cut from the state’s criminal legal and public safety agencies.

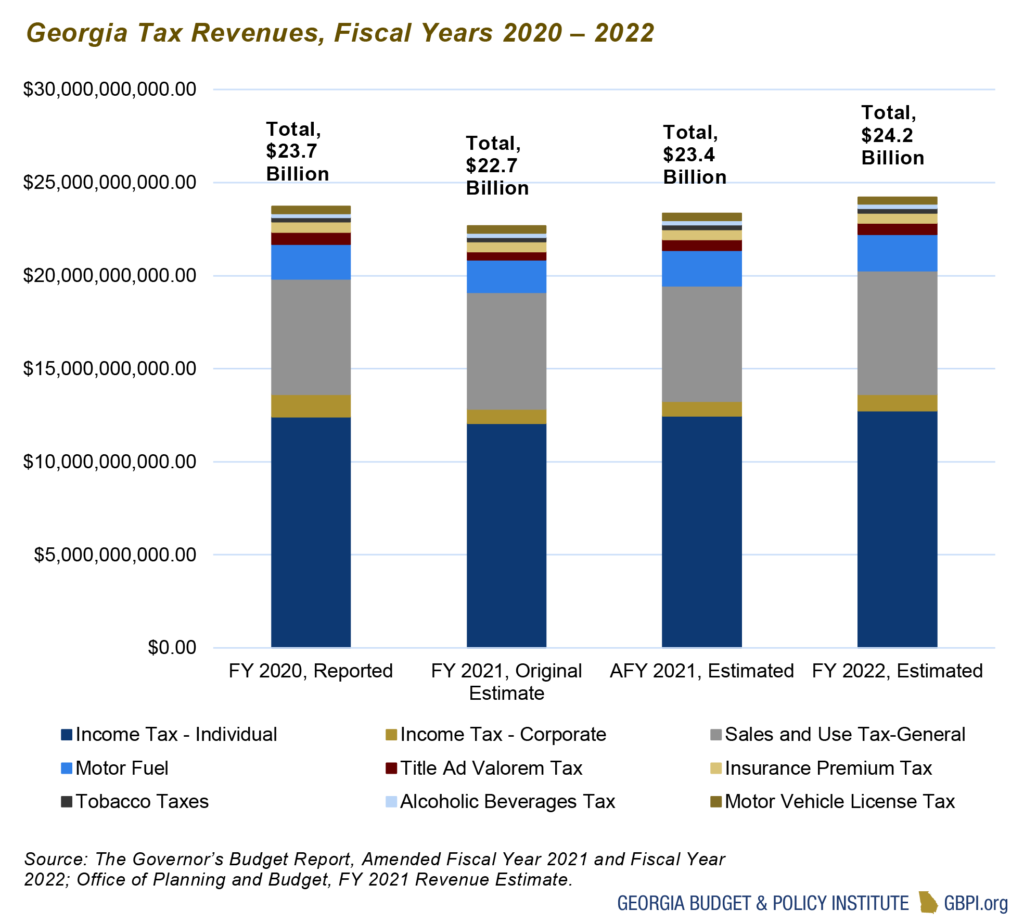

Revenues and General Fund Collections Slow to Rebound from COVID-19

Although Gov. Kemp’s amended budget for FY 2021 is built on a revised revenue estimate, buoyed by $682 million in higher-than-expected tax collections over the original estimate established by the governor, the proposed budget for FY 2021 does not fully benefit from the state’s improved revenue outlook – in part because of a policy decision to return $250 million previously appropriated from the state’s still-robust Revenue Shortfall Reserve (RSR), which the state maintains as a rainy-day fund to draw from when annual revenues cannot sufficiently fund the state’s priorities. Further, the governor’s revenue estimate and budget for FY 2022 allots nothing from the state’s $2.7 billion savings account to help offset the consequences of relatively weak revenue collections expected during the next year. As a result, the governor’s amended budget for FY 2021 falls far short of restoring the deep budget cuts made during the pandemic and keeps spending at a depressed level in FY 2022, well below the level needed to meet Georgians’ needs.

Major federal COVID response legislation included enhanced unemployment benefits, which are taxed by the state, for an extended duration for Georgia workers. As a result, Georgia’s largest revenue source, the individual income tax (50 percent of estimated state General Funds in AFY 2021), has fared better than expected during the pandemic-induced economic downturn. Notwithstanding the likely several-hundred-million-dollar boost to state income tax collections as a result of federal action, Gov. Kemp’s revenue estimate forecasts that Georgia’s sales tax revenues (25 percent of state General Funds) will remain flat in FY 2021, before sharply rebounding during the next fiscal year. Corporate income tax payments (3 percent of state General Funds) are expected to plummet in AFY 2021 and remain nearly 30 percent below pre-pandemic levels during the following fiscal year. Overall, the state expects General Fund revenue collections to grow at slightly over 1 percent between fiscal years 2020 and 2022, a historically weak level of growth.

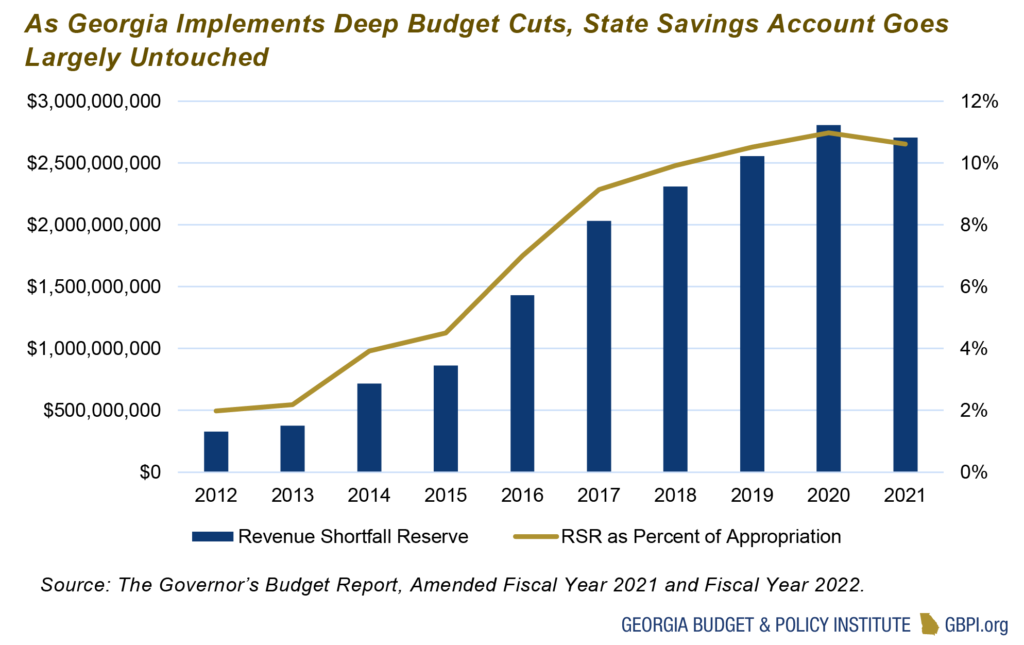

As State Reserves Reach Record Levels, Gov. Kemp Refuses to Leverage RSR to Restore Budget Cuts

The balance of the state’s Revenue Shortfall Reserve (RSR) grows at the end of each fiscal year if there is surplus state revenue—up to a maximum of 15 percent of prior year revenues. Before the Great Recession, the reserves grew to $1.5 billion before lawmakers justifiably tapped the savings to help balance budgets in 2008, 2009 and 2010.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and largely as a consequence of across-the-board budget cuts delivered through lower-than-expected allotments to most state agencies, the state added $489 million to its already near-record reserves at the conclusion of the 2020 fiscal year, boosting the balance of Georgia’s rainy day savings account to $2.7 billion or 10.6 percent of state General Fund revenue collections during the previous year.

The decision to draw from the state’s reserve rests with the state’s governor, along with the unilateral constitutional authority to establish Georgia’s revenue estimate. Although Gov. Kemp previously included $250 million from the state’s RSR to help balance the FY 2021 budget passed in June, the governor’s revised revenue estimate for AFY 2021 removes those funds and the revenue estimate for FY 2022 includes nothing from the RSR to help ease $1.2 billion in continued budget cuts. Now, the balance of Georgia’s state savings account approaches the limit allowed under state law. The policy decision to rely solely on cuts to core areas of government to balance the budget in the midst of a downturn signals a departure from the historically more measured approach of also tapping the RSR to achieve fiscal goals.

Limited Federal Funds Support Teacher Bonus and Georgia Leaders Embark on Risky Partial Medicaid Expansion Plan

Among the few major additions included in Gov. Kemp’s AFY 2021 and FY 2022 budgets is the decision to use approximately $240 million in federal COVID relief funds to provide a one-time $1,000 bonus to teachers and school employees. This addition comes as the state’s funding formula for K-12 schools is set to remain underfunded by $393 million for FY 2022 and does not affect the regular salary schedule for Georgia educators.

Under the partial Medicaid expansion plan put forward by Gov. Kemp, in FY 2022 the state plans to extend eligibility to an estimated 31,000 Georgians earning under 100 percent of the federal poverty level.[4] To pay the costs associated with bringing new enrollees into the state’s Medicaid program Gov. Kemp’s FY 2022 budget proposal includes $68 million in funding to the Department of Community Health (DCH), along with $8 million to the Department of Human Services to help implement the burdensome eligibility requirements set for recipients to qualify for coverage.[5]

Under the partial Medicaid expansion plan put forward by Gov. Kemp, in FY 2022 the state plans to extend eligibility to an estimated 31,000 Georgians earning under 100 percent of the federal poverty level.[4] To pay the costs associated with bringing new enrollees into the state’s Medicaid program Gov. Kemp’s FY 2022 budget proposal includes $68 million in funding to the Department of Community Health (DCH), along with $8 million to the Department of Human Services to help implement the burdensome eligibility requirements set for recipients to qualify for coverage.[5]

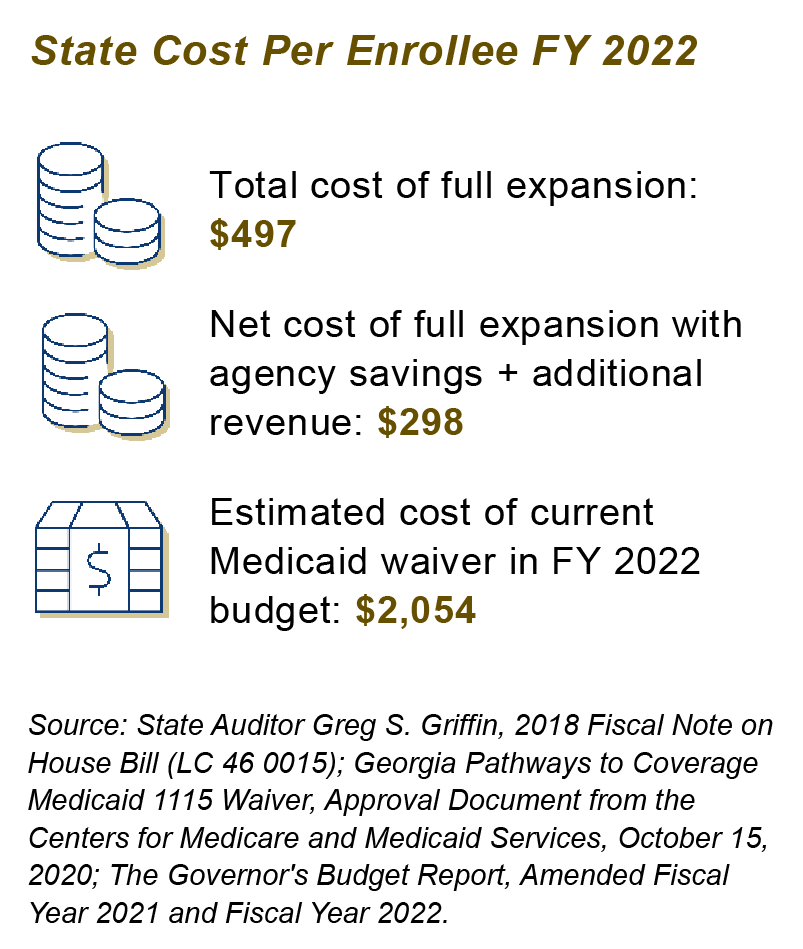

At the same time the state is expending these funds, it is erecting significant barriers, such as work reporting requirements, to prevent hundreds of thousands of those who would otherwise be eligible under the income threshold from obtaining health coverage. Because the state rejected Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), it has foregone the 90 percent funding match offered by the federal government and will spend approximately seven-times the cost per enrollee—$2,054 annually—compared to the $298 net per enrollee cost estimated under full expansion. In fact, in contrast to the state’s current plan, which is set to spend $76 million in FY 2022 to cover about 31,000 Georgians, full Medicaid expansion could cover 482,000 people for about $144 million in FY 2022.[6]

Aside from the partial Medicaid expansion plan’s comparatively low return on investment for Georgia taxpayers, there are additional reasons to fully expand Medicaid: Georgia is gripped by the third wave of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic; it has one of the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rates of any state; Georgia’s uninsured rate remains the third highest in the US, estimated at 13.4 percent of the total 2019 population; rural communities face serious financial challenges compounded by high levels of uninsured residents in the state’s poorest areas; and medical services are vanishing from rural Georgia.[7] Since 2010, nine rural hospitals have closed; although some have reopened as smaller, more limited facilities, many more are struggling to manage uncompensated care, a health care professional shortage and caring for an aging population and chronically ill patients.[8]

Full Medicaid expansion would help ameliorate all these challenges and strengthen a faltering health system at a critical time. Even if the state continues along its current path of implementing the approved Medicaid waivers, action by the Biden Administration to strike down the state’s work requirements and other barriers to accessing care could result in an influx of thousands of newly eligible Medicaid enrollees at a cost up to seven times that of traditional expansion. This risky approach enhances uncertainty around the state’s fiscal outlook for FY 2022 and beyond.

Conclusion

As COVID-19 continues to devastate the lives of Georgia families, with hundreds of thousands of Georgians out of work and millions more facing an increased need for state services, Gov. Kemp’s proposed budgets for AFY 2021 and FY 2022 fail to meet the many challenges facing the state. Instead of drawing on $2.7 billion in current reserves, a massive sum approaching the legal limit of funds that can be saved by the state, the proposed budgets would withhold $1.2 billion from core areas of government, such as public schools, behavioral health services and the Department of Labor.

This failure to adequately fund state government is a policy choice. There are clear options available to state leaders, from leveraging reserves to enacting bipartisan revenue raises, to taking advantage of billions in federal funds left on the table for Georgia’s ailing health care system. Rather than accepting the status quo of policies that are likely to stunt the future growth of the state’s economy and offering little help to families struggling through the COVID-19 pandemic, state leaders begin the budget process with a significant menu of options to improve the outlook for Georgia’s future.

Appendix: Budget Cuts in FY 2022 Budget (from FY 2020)

End Notes

[1] The Governor’s Budget Report, Amended Fiscal Year 2021 and Fiscal Year 2022. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/governors-budget-reports/afy-2021-and-fy-2022-governors-budget-report/download

[2] House Bill 31 (2020), as passed by the Georgia General Assembly and signed by Gov. Kemp. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/appropriations-bills/hb-31-fy-2020-appropriations-bill/download

[3] House Bill 989 (2008), as passed by the Georgia General Assembly and signed by Gov. Perdue; The Governor’s Budget Report, Amended Fiscal Year 2021 and Fiscal Year 2022. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/governors-budget-reports/afy-2021-and-fy-2022-governors-budget-report/download;, Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. Georgia Revenue Primer for State Fiscal Year 2021. https://gbpi.org/georgia-revenue-primer-for-state-fiscal-year-2021/

[4] Georgia Pathways to Coverage Medicaid 1115 Waiver, Approval Document from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (October 15, 2020). https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ga/ga-pathways-to-coverage-ca.pdf

[5] The Governor’s Budget Report, Amended Fiscal Year 2021 and Fiscal Year 2022. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/governors-budget-reports/afy-2021-and-fy-2022-governors-budget-report/download

[6] The Governor’s Budget Report, Amended Fiscal Year 2021 and Fiscal Year 2022. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/governors-budget-reports/afy-2021-and-fy-2022-governors-budget-report/download; Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts, Fiscal Note on House Bill (LC 46 0015), 2018. https://opb.georgia.gov/document/fiscal-notes-2019-health-and-human-services/lc-46-0015-medicaid-expansion-hb-37/download

[7] New York Times. (Jan. 20, 2021). See how the vaccine rollout is going in your state. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/covid-19-vaccine-doses.html; Kaiser Family Foundation. (2019). Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[8] Becker’s Hospital CFO Report. (September 28, 2020). “2 Georgia Hospitals to Close in October.” https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/2-georgia-hospitals-to-close-in-october.html