Key Takeaways

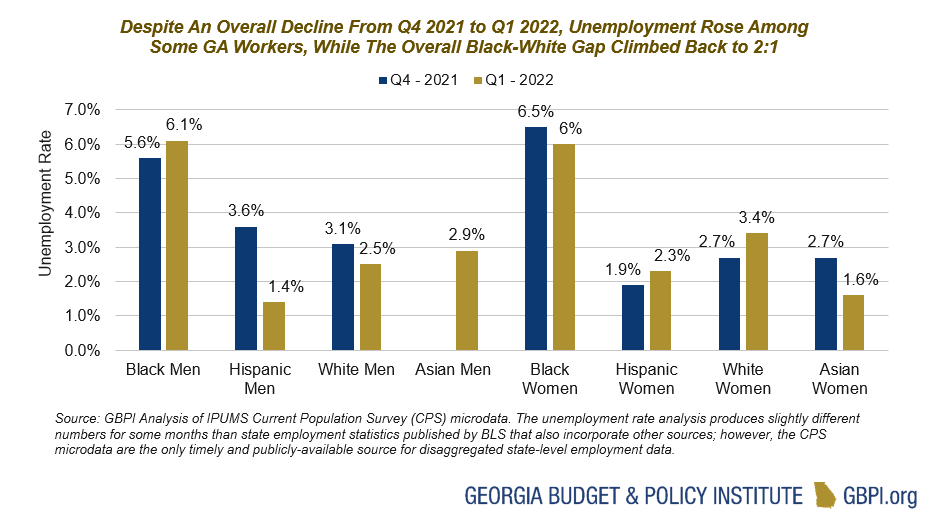

- While March 2022 marked record low unemployment in Georgia at 3.1 percent, underlying inequities persist, as the 2-to-1 unemployment gap among Black and white workers returned in the first quarter of 2022.

- Unemployment among Black Georgians and white women remains significantly higher in Quarter 1 (Q1) 2022 than pre-pandemic Q4 2019.

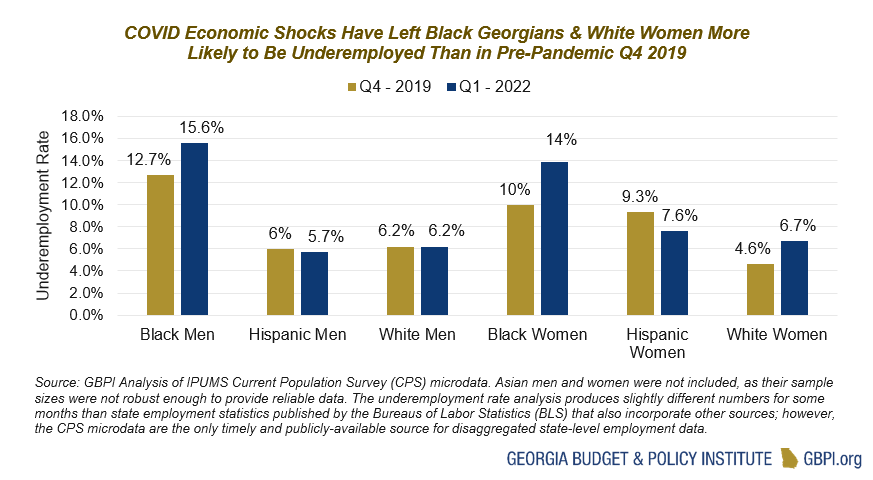

- Compared to pre-pandemic Q4 2019, Black Georgians and white women have been more likely to experience economically scarring underemployment, meaning many have only found part-time work despite their desire for full-time employment.

- Black Georgians, Hispanic women and white women experienced the sharpest rises in long-term unemployment immediately before Georgia’s premature June 2021 cuts to enhanced unemployment benefits and had the highest levels of underemployment by Q1 2022.

Georgia enters its third year of the COVID-19 pandemic recovery following unprecedented federal and state policy responses aimed at preventing long-term economic collapse. Interventions included federal stimulus dollars that boosted otherwise inadequate safety net programs to protect millions of employed and unemployed Georgia workers from deep hardship while maintaining consumer spending at levels that could sustain the flow of critical tax revenue to fund statewide public services.

Despite federal relief efforts that have contributed to Georgia’s ongoing jobs recovery and a revenue surplus that has led to an untapped Revenue Shortfall Reserve that sits at a record maximum of $4.3 billion, state lawmakers have failed to maximize the use of these investments to further strengthen Georgia’s recovery. This failure is possibly driven by harmful policy stances, which suggest that federal relief efforts have led to more economic harms than benefits. These dangerous stances have likely led to delays in the allocation of $4.7 billion in American Rescue Plan (ARP) fiscal recovery funds to target vulnerable workers and families that have yet to reach full recovery and premature cuts to federal enhancements to Georgia’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) safety net, leaving hundreds of thousands of involuntary unemployed Georgians without wage protections while they sought suitable work.

While billions of unused federal recovery dollars leave questions as to how much further along, and more equitable, Georgia’s recovery would be at this point, critics attribute the pandemic federal stimulus response to be the sole or primary cause of rapid inflation, despite evidence of corporate profits and price changes tied to certain goods becoming less available because of supply chain challenges. Critics also malign enhanced relief efforts aimed at protecting the involuntary jobless, despite near-recent and new evidence that shows that enhanced unemployment benefits were not the cause of labor shortages. These critiques likely hold no regard for persisting barriers to stable employment that remain for women, Black or Hispanic workers of color, nor for wage gaps among those same Georgians whose earnings have been the slowest to keep pace with inflation.

Economic downturns and economic stimulus efforts that end without meaningful consideration of the ensuing equity impact to vulnerable families often leave Georgia workers of color exposed to the fiercest harms, adding layers of hardship to those who already disproportionately navigate at or below livable economic margins. These margins include but are not limited to food, finances and quality job security. In the absence of intentional anti-racist policy choices to reverse harms brought by policy choices steeped in anti-Black, anti-women and anti-immigrant sentiment, each coming recession threatens to further harm the economic prosperity of women, immigrants and Black and Hispanic workers of color.

The latest Georgia workforce data shows continued positive steps towards recovery in select areas, including growth in non-farm employment, declines in the total numbers of unemployed Georgians and overall growth in the total number of workers who either have jobs or are actively seeking them. However, similar to what happened a year ago, disaggregated data shows how some Georgians are much further along a road to recovery than others.

In the aftermath of premature pandemic social safety net cuts and inadequate workforce investments to address inequity gaps across race, ethnicity and gender, unemployment has in fact worsened for certain Georgians from pre-pandemic to now. And even among those who have found employment, there is a widening gap that has left white women and Black Georgians more likely to be underemployed, or to wish for full-time employment but finding only part-time work.

Georgia Job Trends: Moving Into Year Three of the COVID Pandemic Recovery

Since the start of the pandemic, which led to the bleeding of 609,000 non-agriculture jobs from February 2020 to April 2020, Georgia has rebounded with a net gain of over 678,000 jobs as of March 2022, led by job growth in Hospitality, Professional and Business Services, Trade and Transportation and the private Education and Health industries. This constitutes a 109 percent gain in employment since April 2020 losses, signaling an ongoing recovery in the aggregate. While these are signs of progress, Georgia remains nearly 87,000 jobs behind where its projected growth would be if the COVID pandemic never occurred.

Despite the net employment gains when totaling job changes across all major industries in Georgia, some have faced challenges in regaining all of the payroll jobs lost in the pandemic, including the Hospitality industry, which as of March 2022, regained 84 percent of the 223,000 jobs lost in early 2020, and the public sector which has suffered a loss of nearly 19,000 public sector jobs across federal, state and local government employers in Georgia, including more than 15,000 state public sector jobs alone. This constitutes an almost 9 percent net job loss in all state public sector employment since February 2020. In efforts to address current public sector hiring challenges, the state legislature passed new budgets that include cost-of-living adjustments and pay increases for public sector workers.

While current hiring challenges across some industries have often been singularly portrayed as one where employers struggle to meet the rising demands for higher wages by prospective workers, the dynamics in Georgia are much more complex. All these dynamics, however, fall on the fault lines of persistent disparities across race, ethnicity and gender. Despite what may be temporary leverage that has boosted pay for some Georgia workers, it has not closed decades-growing gaps in wage inequality across race, ethnicity and gender. Also, as more Georgians return to the workforce, hiring needs will likely subside and weaken worker leverage that has led to pay increases. Lastly, many Georgians still face health-related and dependent care barriers to employment or worker training.

These disparities have widened during the pandemic recovery, as part of recent and years-long state and federal policy choices that: restrict access to the social safety net while economically vulnerable workers in Georgia, disproportionately those of color, are in fragile periods of recovery from economic downturns; fail to make long-term, targeted investments in workforce development programs to prioritize positive employment outcomes across race and ethnicity; fail to provide adequate work supports that include a state Earned Income Tax credit, paid leave and broadly accessible child care subsidies; and continually weaken local governments’ ability to improve job quality in their unique workforce climates. Contrary to improvements in overall job numbers and unemployment, there have been several consequences to these policy choices that are only visible when disaggregating measures of Georgia’s workforce.

Georgia’s High Job Quit Rate Offers Evidence of Georgia Workers Seeking Job Transitions in Multiple Ways

Since the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) began publishing monthly state-level data on job openings and job churn, Georgia has remained near the top among all states in the level of workers who quit their jobs. In February, Georgia ranked second in the country in the job quit rate, reflecting Georgia workers exercising their current leverage to seek better jobs. This leverage is in one way measured by Georgia’s high ratio of job openings compared to unemployed workers, which in February had 2.7 job openings for every jobless worker in Georgia. But while some workers have used this leverage to transition to more suitable jobs, other active jobseekers who have been scarred by long-term unemployment or from being out of the workforce for long periods because of health or dependent care reasons may find greater challenges returning to traditional employment. This is particularly true as employers have been known to raise educational and experience requirements when the number of available workers compared to job openings grows.

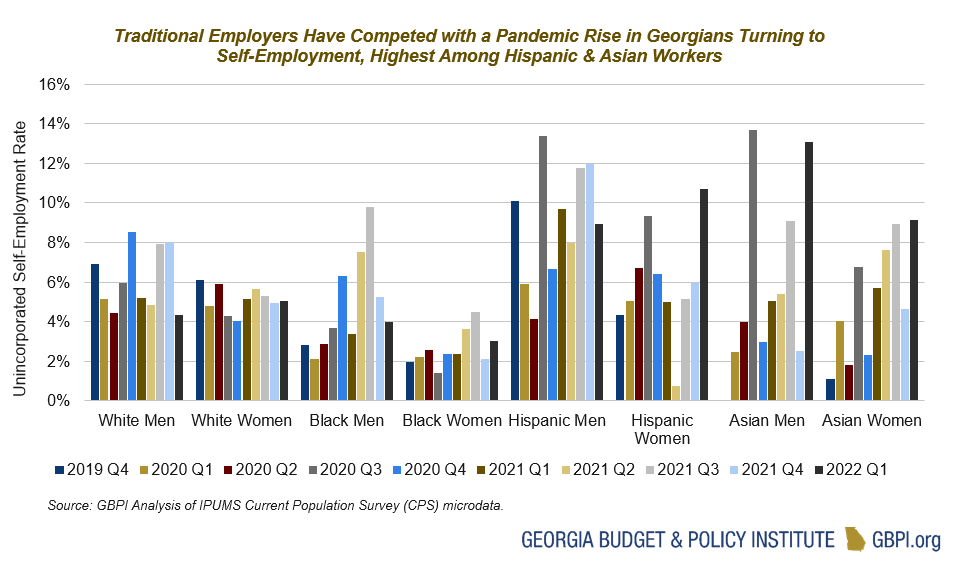

Within this evolving pandemic workforce climate, data shows that some Georgians have turned to unincorporated self-employment, defined as non-traditional jobs that are classified as independent contractors or gig workers, at higher rates during the COVID recovery than during periods immediately before COVID. Signaling Georgia workers’ desire to find possibly safer and more flexible employment following COVID-19 heightened public health risks, Black, Hispanic and Asian workers turned more heavily to self-employment, for their primary or secondary means of employment. From Q4 2019 to Q1 2022, unincorporated self-employment had a net increase of 42 percent for Black men, 54 percent for Black women, while more than doubling for Hispanic women, climbing 9 times higher for Asian women and 13 times higher for Asian men.

Georgia’s pandemic-era rise in unincorporated self-employment heightens long-held concerns over job quality and worker protections for non-traditional workers. Independent contractors and app-based gig workers are not entitled to UI benefits, paid sick days, health and safety protections, nor to paid family nor medical leave protections. While unincorporated self-employment can provide a gateway into entrepreneurship or allow otherwise unemployed workers to maintain consistent work history to maintain a bridge to traditional employment, Georgia workers who primarily rely on self-employment income often risk their professional and personal health by working without adequate labor standard protections.

Digging Deeper Than Georgia’s Unemployment Rate

Georgia’s overall unemployment rate in March 2022 reached a pandemic low of 3.1 percent, a steady decline from 4.4 percent in March 2021, and the lowest monthly unemployment level ever recorded for the state. This measure of Georgia’s unemployed active jobseekers, however, is not an adequate barometer on its own to measure Georgia’s workforce health, as it masks other underlying dynamics across race, ethnicity and gender, and only offers a more complete analysis of Georgia’s workforce when viewed alongside: labor force participation, which is the sum of Georgians that either have jobs or are jobless and actively looking; long-term unemployment, or the share of those in the labor force who have been unemployed for at least 27 weeks and are actively looking for work; and underemployment, the share of the labor force that is either unemployed, working involuntarily part-time or has looked for work in the last 12 months but has given up actively seeking work in the last four weeks (also known as marginally attached).

Black Men

A deeper look into state-level data reveals an increase in unemployed active jobseekers among Black men in Georgia, with a 5.6 percent unemployment rate in Q4 2021, to 6.1 percent in Q1 2022. Over that same period, their labor force participation grew from a rate of 61.5 percent to 62.4 percent, an indication that more Black men found jobs or began actively searching for them. However, the likelihood of unemployment for Black men has worsened over the entire pandemic recovery, as they experienced a rate of 5.1 percent in Q4 2019, which is 1 percent lower than their latest Q1 2022 measure. They have experienced this same pandemic pattern with underemployment and long-term unemployment.

Underemployment provides a broader labor market measure, including those who are unemployed, as well as those who want full-time work but can only find part-time work due to economic reasons and those who are jobless and have sought employment within the last year but not in the last four weeks. It sharply increased to 15.6 percent among Black men in Q1 2022, from 12.3 percent in the previous quarter, the sharpest increase among all Georgia workers during this period. Black men in Georgia also experienced a net increase of 2.9 percent from Q4 2019 to Q1 2022.

Compared to full-time work, involuntary part-time work has a greater likelihood of having unstable and unpredictable work schedules, which research has found leads to higher worker turnover, household economic insecurity and reductions in the health and well-being of workers and their families. Adding insult to injury, SB 331 passed out of the legislature and was signed by the governor, stripping more power from local governments to address worker justice issues, specifically barring them from regulating fair scheduling within their unique workforces and standards that employers use to pay workers whose wages are based on a measure of their productivity.

Black men were also most likely to be long-term unemployed active jobseekers in the first quarter of this year, with a 2.8 percent long-term unemployment rate that is significantly higher than Asian women (1.6 percent), nearly triples that of white men (1 percent) and is almost ten times that of white women (0.3 percent). Furthermore, long-term unemployed active job-seeking Black men comprised 46 percent of all unemployed Black men in Q1 2022, second only to Asian women.

Underemployment is often a by-product of long-term unemployment, as many who suffer long durations of unemployment end up choosing unsuitable part-time jobs out of desperation. Georgia’s premature cuts to enhanced federal UI benefits in June 2021 likely contributed to rising underemployment and long-term unemployment among Black men in the pandemic recovery and exits from the labor force. Their long-term unemployment rate in the quarter immediately preceding the cuts was 2.5 percent, higher than all other Georgia workers. Consequently, from Q2 2021, before Georgia’s premature enhanced UI cuts, to Q1 2022, there was a 3.3 percent net reduction in their labor force (employed Black men and those who are unemployed but active jobseekers), partially driven by a reduction among prime-age working Black men ages 25 to 54 with young children in their household. Within this net labor force reduction, data shows movement that includes a:

- 2 percent net reduction in unemployed Black men due to them either finding jobs or leaving the labor force;

- 6 percent net reduction in employment among all non-institutionalized Black men, who either became unemployed or left the labor force altogether; and a

- 15 percent rise in the long-term unemployed share of all unemployed Black men, from 31 percent in Q2 2021 to 46 percent in Q1 2022.

Altogether, while there have been fewer unemployed job-seeking Black men, the net reduction in their employed population means there was no net increase in the flow of unemployed Black men into employment. Instead, more unemployed Black men flowed out of the labor force altogether than those who flowed into employment, particularly among workers younger than 25 and those older than 54, who were likely discouraged by a lack of success in finding suitable jobs. Prime-age Black men with children under 5 likely had a small reduction in labor force participation due to continued instability in Georgia’s child care infrastructure. Furthermore, among those who remained unemployed, a larger share of them became long-term unemployed, likely due to a combination of factors including hiring discrimination, eroding professional networks, and the loss of wage protections that could support them and facilitate access to job training that could better position them to find suitable employment. And among those who found employment over that period, a growing share of Black men were only successful in finding part-time jobs.

Black Women

Unemployment among Black women declined from 6.5 percent in Q4 2021 to 6 percent in Q1 2022. However, as with Black men in Georgia, it remains higher than pre-pandemic Q4 2019, which was 4.9 percent. Among prime working age Black women, those ages 25 to 54, labor force participation grew among those without children and those with young children ages 5 and younger, 76.3 to 79.9 percent and 72.5 to 74.6 percent, respectively. It sharply declined for prime-age workers with a child between 6 and 17 years old, from 90.2 percent in Q4 2021 to 82.8 percent in Q1 2022, altogether resulting in little change in prime-age Black women’s overall labor force participation between those periods. However, all Black women ages 16 and older saw a decline in labor force participation from 64 percent to 60.7 percent over the same period, signaling that young workers ages 16 to 24 and those older than 54 left the labor force due to several reasons including retirement, school, care reasons or public health concerns.

While unemployment declined in Q1 2022 for Black women, it has returned to doubling that of all Georgians except for white women, signaling the rising recovery gap that continues to leave Black women out of an equitable recovery in Georgia’s workforce. Underemployment among Black women has also returned to a gap that is more than double their white counterparts, as white women experienced declining underemployment that reached a rate of 6.7 percent in Q1 2022, white men experienced a decline to 6.2 percent, while Black women experienced an increase that reached 13.9 percent. Signaling a return to the structurally racist equilibrium in Georgia’s labor market, underemployment grew in Q1 2022 for only Black men and women in Georgia, and the 2-to-1 ratios in unemployment and underemployment returned among Black and white workers.

There is nothing “natural” about this disparity. Rather, it is rooted in systemic racism that includes the “last hired, first fired” phenomenon; the long-term destructive legacy of slavery; the gross overrepresentation of Black men and Black women within the criminal legal system, leading to carceral control that includes imprisonment, probation, parole and unjust criminal fines and fees practices that create or perpetuate employment barriers; occupational segregation that disproportionately places Black women and men into unstable jobs with few to no worker protections; and an unemployment insurance system that disproportionately excludes Black and Hispanic Georgians from wage protections that could lead to more suitable, quality jobs instead of unstable ones that perpetuate a cycle of unemployment.

The likelihood of long-term unemployment and the share of long-term unemployed Black women among all unemployed Black women have grown over the last few years and were not mitigated by the premature cuts to enhanced UI in June 2021. Only Black women and men have seen rising long-term unemployment since those cuts among all Georgians. In Q2 2021, immediately before the June 2021 cuts, Black women had a long-term unemployment rate of 1.6 percent. By Q1 2022, they experienced a long-term unemployment rate of 1.7 percent.

The Cyclical Relationship Between Economic Inequality and the Criminal Legal System

State and federal lawmakers have repeatedly made policy choices to deal with economic failures through the criminal legal system. Formerly incarcerated Georgians often experience joblessness and poverty long before contact with the criminal legal system. Policies that reinforce or incentivize mass incarceration, which has led to the overrepresentation of Black and Hispanic Georgians in jails and state and federal prisons, only heighten employment barriers for returning citizens. These harmful policies include, but are not limited to: driver’s license suspension for failure to pay court debt; restrictions that incarcerate impoverished, criminal-legal-system-facing Georgians simply because they cannot afford bail; and unjust court fines and fees practices that disproportionately extract wealth from impoverished communities and families of color and often place them into spiraling incarceration and debt. And for those who manage to find employment, job options are often limited, unstable and create job churn that contributes to more frequent unemployment spells, underemployment and long-term unemployment disparities particularly experienced by Black Georgians.

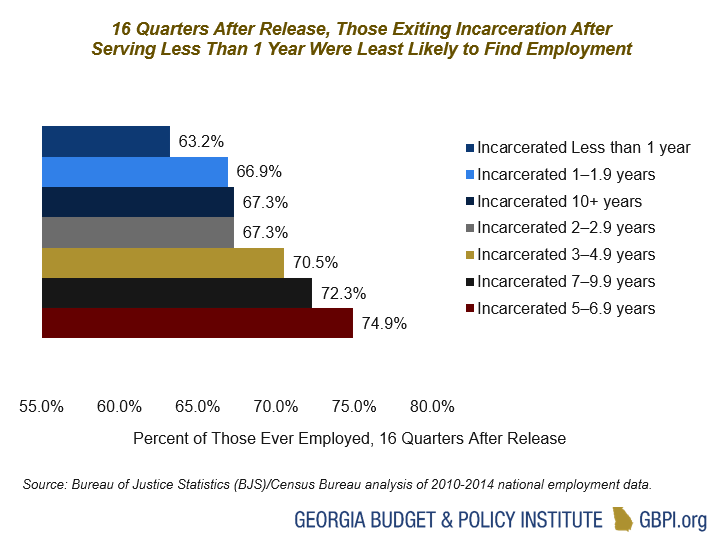

Recent federal data released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics provides the latest insights on the negative employment impacts of mass incarceration. These data reveal that even for those who served minimal periods of incarceration, they often experience the greatest barriers to stable employment. While these are nationally representative figures from those released from federal prisons, they shed light on the broader impacts that incarceration can have on the employment prospects for returning Georgians.

Hispanic Women

Hispanic women have been the most vulnerable to economic shocks among all Georgia workers. Several labor market measures demonstrate large swings in the health of their workforce across the pandemic recession and recovery timeline. While they experienced a net Q4 2019 to Q2 2022 unemployment decline from 4.5 percent to 2.3 percent, they experienced the sharpest unemployment increase among all Georgians, rising from 6.6 percent in Q1 2020 to 19.2 percent in Q2 2020. Hispanic women have experienced similar patterns in underemployment, with a net Q4 2019 to Q1 2022 decline from 9.3 percent to 7.6 percent, while having the sharpest quarter-to-quarter rises, evidenced by Q1 2020 levels so small that no underemployment statistic was available, but climbing to 38.1 percent underemployment in Q2 2020.

Like other workforce measures, Hispanic women have experienced some of the sharpest rises in long-term unemployment from quarter to quarter. From Q4 2020 to Q1 2021, it rose to 4.5 percent, reaching the highest level among all working Georgians during any quarter within the pandemic recovery.

Furthermore, 88 percent of all unemployed Hispanic women in Q1 2021 were long-term unemployed. While long-term unemployment largely subsided for Hispanic women by Q1 2022, ethnic and gender gaps within underemployment persist, leaving them more likely to experience it than their white and Asian counterparts. Behind only Black men and Black women in Georgia’s workforce, Hispanic women enter the latest recovery phase with the third-highest likelihood of finding only part-time work despite a desire for full-time work. Despite net declines in unemployment and underemployment across the broader pandemic recovery, these data reveal an underlying harmful trend: while Hispanic women have and continue to experience some of the worst periods of pandemic-induced labor force barriers, too often their recovery path has led to jobs with fewer hours that likely lead to smaller paychecks and greater instability. These trends could also result from pandemic periods in which they experienced relatively steep long-term unemployment.

Furthermore, labor force participation among Hispanic women ages 16 and older significantly declined from Q4 2021 (66 percent) to 57.7 percent in Q1 2022. Even worse, it fell by more than 12 percent, 69.1 percent to 56.8 percent, among prime working-age Hispanic women during the same period. This follows a broader pandemic trend of decline in labor market participation among Hispanic women, particularly among prime-age workers between 25 and 54, who have yet to regain consistent traction in the labor force. Compared to Q4 2019, their prime working-age labor force participation in Q1 2022 has experienced a net decline of 6 percent.

Asian Women

Workforce narratives within the Asian community are highly diverse, particularly among Asian women, but current data limitations only allow for broad measures of their experiences in Georgia. While disparities, such as those often present between Burmese and Taiwanese women, aren’t currently visible, broader trends still demonstrate pandemic recovery gaps between Asian women and other Georgians. At only 1.6 percent in Q1 2022, Asian women experienced lower unemployment compared to 2.2 percent in Q4 2019, and their likelihood of joblessness was lower than almost all Georgians by Q1 2022. However, their lower unemployment levels are largely attributed to Asian women who remain out of the labor force following pandemic exits that likely result from broader pandemic workforce dynamics affecting Asian women: living in multi-generational families and carrying more care responsibilities instead of risking COVID exposure in frontline industries, and reluctance to return to work because of anti-Asian public harassment stemming from xenophobic messaging circulated throughout the pandemic. Evidence reveals lower labor force participation rates among prime-aged Asian women in Q1 2022, as their participation remains nearly 3 percent lower than in Q4 2019 (65.7 percent in Q1 2022 compared to 68.2 percent in Q4 2019).

Second to only Hispanic women, Asian women in Georgia experienced sharp increases in long-term unemployment and underemployment during the height of the pandemic-induced economic downturn. By Q4 2020, Asian women were more likely than all other Georgians to experience long-term unemployment, reaching a peak of 3.2 percent. By Q1 2022, their long-term unemployment levels declined to 1.6 percent but remained second-highest and behind only Black Georgians. While long-term unemployment often increases the likelihood of seeking or accepting part-time work, it can also reduce one’s ability to afford workforce training and can be perceived by employers as a reason to offer lower wages. These dynamics likely perpetuate the wage gap that leaves Asian women and Black Georgians, who remain most likely to experience long-term unemployment spells, further behind other workers in Georgia.

Along with their long-term unemployment spikes, Asian women in Georgia experienced pre-pandemic underemployment levels that were too low to be reliably measured in Q4 2019, followed by a rise to more than 24 percent by Q3 2020. While sample sizes are not large enough to determine the latest extent of underemployment among Asian women in Georgia, and economic conditions can vary based on the community of origin among Asian women, national research finds that 20 percent of Asian American and Pacific Islander women held part-time jobs in March 2022. These data reflect the broader vulnerability of Asian women in the workforce, and provide more evidence to the workforce crisis that persists for women and Black, Hispanic and Asian workers of color in Georgia.

Conclusion

Despite a record low 3.1 unemployment rate in March 2022, a more holistic and disaggregated view of Georgia’s labor market reveals that the pandemic-induced economic crisis, largely felt by Black and Hispanic workers of color, has shifted. While last year’s crisis led to more widespread unemployment, Georgia has now returned to systemically racist unemployment gaps, and rising underemployment, particularly felt by Black men, Black women and Hispanic women, which could be attributed to disparities among Black and Hispanic workers of color in long-term unemployment through much of the pandemic to now. These disparities result from policy choices that have not prioritized equitable workforce investments, maintain an unjust criminal legal system and have continually eroded Georgia’s social safety net.

Recent safety net policy choices, led by harmful impulses to prioritize business interests over worker protections, have only added insult to injury. Georgia’s premature June 2021 cuts to enhanced UI benefits harmed hundreds of thousands of involuntary jobless Georgians, likely creating economic scarring to vulnerable Georgia workers for years to come. Furthermore, efforts were made during Georgia’s 2022 Legislative Session to suppress employers’ shared responsibility of funding the UI Trust Fund that provides UI benefits to the involuntary jobless, which would have incentivized the Georgia Department of Labor to reduce Georgia workers’ access to UI benefits as a means of compensating for insufficient revenue from employer taxes. While these efforts were unsuccessful this year, they are reminders that the prioritization of business interests over worker protections remains ever-present.

To challenge policymakers who believe that eroding worker protections are an acceptable means of remaining the “No. 1 state to do business,” the production and use of racially disaggregated state-level labor market data must become a norm. To hold informed conversations that consider the past, present and future implications of Georgia’s safety net, workforce development and criminal legal systems policies, institutionalizing policymakers’ use of this data is imperative. The economic security and prosperity of all Georgians are only possible when our decision-making intentionally centers humanity through a racial, ethnic and gender equity focus. Without such, overall data points such as a record 3.1 percent March 2022 unemployment rate will continue to mask unacceptable disparities in Georgia and permit a “see-no-evil” approach to racist economic policies.